The Bible doesn't state that it should be read literally - yet an all-or-nothing approach is the core of many Christians' faith.

Where does biblical literalism come from? What is the genesis, if you will, of the habit of mind that makes many Christians read the Bible with a different brain to the one they'd use with any other writing?

It is by no means an essential Christian tenet. No creed says anything about how to read the scriptures. The highest claim the Bible makes for itself is when the writer of Paul's letter to Timothy says the Hebrew scriptures were "God-breathed", which is wonderfully suggestive but hardly precise or dogmatic. I mean, Adam was God-breathed, and look what happened to him.

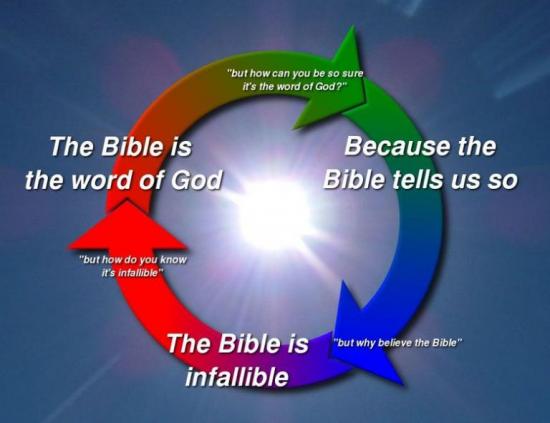

The Bible is the word of God, Christians believe, but why should the fact it's God's mean it has to be read with naive absolutism? Many Christians call the church "the body of Christ" without considering it anything like infallible, or refusing to see its rites as symbolic.

Part of the problem is historical. The deification of the Bible is a result of the Protestant reformation. Before then, the final authority, the ultimate arbiter and source of information in religious matters was the church, with its ancient traditions and living experts. When Luther and friends opposed the teaching of the Catholic hierarchy, they needed a superior authority to appeal to, which was provided by the Bible.

Fair enough. But in defending or reclaiming the Bible from papists and then liberals, evangelical Protestants made it the very heart of the faith. Hence the ludicrous situation where many evangelical organisations, such as the Southern Baptist Convention, have statements of faith where the first point is the Bible, before any mention of, for example, God. Hence the celebrated idolatrous aphorism of William Chillingworth: "The BIBLE, I say, the BIBLE only, is the religion of Protestants!".

One practical problem of this text mania is that the Bible, unlike the church, can't answer questions, clarify earlier statements, arbitrate disagreements or deal with new developments. So those in search of religious certainty have to find it all in the text: if it says the earth was created in six days, or that gay sex is an abomination, them's the facts, end of story. And if it forbids charging interest, well there's always wriggle room.

The other practical problem is that for more moderate Christians, Christ is the heart of the faith, and the Bible offers information and ideas about him and is one of the things that point us in his direction. But if the Bible itself is the heart, then to read it is to enter the Holy of Holies, making it that much harder to accept any normal human ambiguity or inaccuracy in its words.

This effect is magnified by a more recent historical development: the charismatic movement. Even among evangelicals who don't speak in tongues or put their hands in the air when the sing Shine Jesus Shine, the movement has had profound effects, one of which is that they don't read the Bible just to be reminded and shaped by its teaching, but to hear what God has to say to them today.

If you read the Bible asking: "What was St Paul saying to the Galatians?" all kinds of critical questions arise: How would first-century Asia Minor have understood these words? Would Paul have phrased it differently to a church he was less pissed off with? Would other witnesses have recalled the events he describes differently? But if you read the Bible asking: "What is God saying to me today?" it seems less appropriate to do anything but accept it at face value.

One last factor in biblical all-or-nothingism is the part that biblical criticism plays in evangelical conversion, which is none at all.

People who convert to evangelical Christianity, including those who grow up with it, are persuaded by the experience of a religious community, and by finding that evangelical theology seems to hold water. All this is totally underpinned by the Bible – it's the foundation and guarantee. But the only test of its reliability that inquirers are invited to make is to read it and ask "Is this something that I can accept wholesale and entrust my life to?"

It's generally much later that a convert will have to consider concrete evidence that biblical writers were human beings, capable of being one-sided, of writing myth, of exaggerating, of guessing, of having opinions it's impossible to agree with.

Some of us, faced with this evidence, shape our faith in the light of it, making the Bible a far more fascinating, revealing and diverse record of human religious experience. But it's not surprising if for others the evidence comes as an attack that threatens to undermine the foundation of their faith, and has to be beaten off blindfold.

"Biblical Literalism And The Cultivation Of Hatred"

https://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2012/02/biblical-literalism-and-cultivation-of.html

https://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2012/02/biblical-literalism-and-cultivation-of.html

A Classic Tautology

Biblical Literalism: Not Only Impossible But Destructive Of Meaning And Souls

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2013/09/biblical-literalism-not-only-impossible.html

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete