In 1647, British Parliament banned the celebration of Christmas

Puritan era

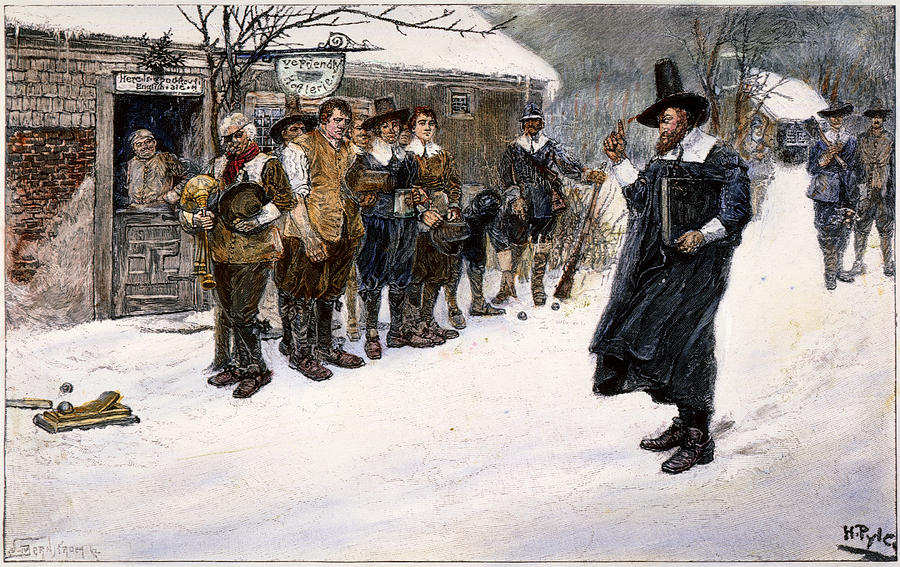

The first documented Christmas controversy was Christian-led, and began during the English Interregnum, when England was ruled by a PuritanParliament.[19] Puritans sought to remove elements they viewed as pagan (because they were not biblical in origin) from Christianity (see Pre-Christianity above). In 1647, the Puritan-led English Parliament banned the celebration of Christmas, replacing it with a day of fasting and considering it "a popish festival with no biblical justification", and a time of wasteful and immoral behavior.[20] Protests followed as pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalistslogans.[21] The book The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652) argued against the Puritans, and makes note of Old English Christmas traditions, dinner, roast apples on the fire, card playing, dances with "plow-boys" and "maidservants", old Father Christmas and carol singing.[22]The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 ended the ban, but many clergymen still disapproved of Christmas celebration. In Scotland, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland also discouraged observance of Christmas. James VI commanded its celebration in 1618, but attendance at church was scant.[23]

In Colonial America, the Puritans of New England disapproved of Christmas, and celebration was outlawed in Boston from 1659 to 1681.[24][25][26]The ban by the Pilgrims was revoked by English governor Edmund Andros, however it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region.[27] By the Declaration of Independence in 1776, it was not widely celebrated in the US.[25]

The first documented Christmas controversy was Christian-led, and began during the English Interregnum, when England was ruled by a PuritanParliament.[19] Puritans sought to remove elements they viewed as pagan (because they were not biblical in origin) from Christianity (see Pre-Christianity above). In 1647, the Puritan-led English Parliament banned the celebration of Christmas, replacing it with a day of fasting and considering it "a popish festival with no biblical justification", and a time of wasteful and immoral behavior.[20] Protests followed as pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities and for weeks Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalistslogans.[21] The book The Vindication of Christmas (London, 1652) argued against the Puritans, and makes note of Old English Christmas traditions, dinner, roast apples on the fire, card playing, dances with "plow-boys" and "maidservants", old Father Christmas and carol singing.[22]The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 ended the ban, but many clergymen still disapproved of Christmas celebration. In Scotland, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland also discouraged observance of Christmas. James VI commanded its celebration in 1618, but attendance at church was scant.[23]

In Colonial America, the Puritans of New England disapproved of Christmas, and celebration was outlawed in Boston from 1659 to 1681.[24][25][26]The ban by the Pilgrims was revoked by English governor Edmund Andros, however it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region.[27] By the Declaration of Independence in 1776, it was not widely celebrated in the US.[25]

Alan: I have long held that "puritanism" is the root of many - if not most - evil.

I define "puritanism" as "the dictatorial desire" to make human life purer than "God Himself" intended it to be.

Trappist monk, Fr. Thomas Merton cuts to the quick.

"The terrible thing about our time is precisely the ease with which theories can be put into practice. The more perfect, the more idealistic the theories, the more dreadful is their realization. We are at last beginning to rediscover what perhaps men knew better in very ancient times, in primitive times before utopias were thought of: that liberty is bound up with imperfection, and that limitations, imperfections, errors are not only unavoidable but also salutary. The best is not the ideal. Where what is theoretically best is imposed on everyone as the norm, then there is no longer any room even to be good. The best, imposed as a norm, becomes evil.”

"Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander,” by Trappist monk, Father Thomas Merton

More Merton Quotes

I strongly recommend the 2009 anime' version of "A Christmas Carol," a Disney production with Jim Carrey "doing all the voices."

In this remarkably faithful rendition of Dickens' story, Carrey is not his typically gooney self but does masterful work imparting abundant Dickensian life to "all the characters.

Carrey's performance is a "tour de force."

Pope Francis Joins The War On Christmas

Calling The Celebration "A Charade"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2015/11/pope-francis-joins-war-on-christmas.html

I define "puritanism" as "the dictatorial desire" to make human life purer than "God Himself" intended it to be.

Trappist monk, Fr. Thomas Merton cuts to the quick.

"The terrible thing about our time is precisely the ease with which theories can be put into practice. The more perfect, the more idealistic the theories, the more dreadful is their realization. We are at last beginning to rediscover what perhaps men knew better in very ancient times, in primitive times before utopias were thought of: that liberty is bound up with imperfection, and that limitations, imperfections, errors are not only unavoidable but also salutary. The best is not the ideal. Where what is theoretically best is imposed on everyone as the norm, then there is no longer any room even to be good. The best, imposed as a norm, becomes evil.”

"Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander,” by Trappist monk, Father Thomas Merton

More Merton Quotes

I strongly recommend the 2009 anime' version of "A Christmas Carol," a Disney production with Jim Carrey "doing all the voices."

In this remarkably faithful rendition of Dickens' story, Carrey is not his typically gooney self but does masterful work imparting abundant Dickensian life to "all the characters.

Carrey's performance is a "tour de force."

In this remarkably faithful rendition of Dickens' story, Carrey is not his typically gooney self but does masterful work imparting abundant Dickensian life to "all the characters.

Carrey's performance is a "tour de force."

Pope Francis Joins The War On Christmas

Calling The Celebration "A Charade"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2015/11/pope-francis-joins-war-on-christmas.html

The Puritan War On Christmas

The Puritan War On Christmas

During the seventeenth century, as now, Christmas was one of the most important dates in the calendar, both as a religious festival and as an important holiday period during which English men and women indulged in a range of traditional pastimes. During the twelve days of a seventeenth-century Christmas, churches and other buildings were decorated with rosemary and bays, holly and ivy; Christmas Day church services were widely attended, gifts were exchanged at New Year, and Christmas boxes were distributed to servants, tradesmen and the poor; great quantities of brawn, roast beef, 'plum-pottage', minced pies and special Christmas ale were consumed, and the populace indulged themselves in dancing, singing, card games and stage-plays.

Such long-cherished activities necessarily often led to drunkenness, promiscuity and other forms of excess. In fact the concept of 'misrule', or a ritualised reversal of traditional social norms, was an important element of Christmas, and has been viewed by historians as a useful safety-valve for the tensions within English society. It was precisely this face of Christmas, however, that the Puritans of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England found so objectionable. In the 1580s, Philip Stubbes, the author of The Anatomie of Abuses, complained:

That more mischief is that time committed than in all the year besides,

what masking and mumming, whereby robbery whoredom, murder

and what not is committed? What dicing and carding, what eating and

drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used, more than in all

the year besides, to the great dishonour of God and impoverishing of the

realm.

In addition to this association with immorality and the concept of misrule, another of the central objections to the feast for the stricter English Protestants between 1560 and 1640 was its popularity among the papist recusant community. Within the late medieval Catholic church, Christmas had taken a subordinate position in the liturgical calendar to Easter. Its importance, however, had been growing and was further enhanced by the religious conflicts of the sixteenth century, for whereas, as John Bossy has recently pointed out, the more extreme Protestants had little time fox Christ's 'holy family', reformed Catholicism laid great stress on this area. The Tridentine emphasis on devotions to the Virgin Mary in particular elevated the status of the feast during which she was portrayed as a paragon of motherhood.

Certainly, English recusants seem to have retained a deep attachment to Christmas during Elizabeth I's reign and the early part of the seventeenth century. The staunchly Catholic gentlewoman, Dorothy Lawson, celebrated Christmas 'in both kinds... corporally and spiritually', indulging in Christmas pies, dancing and gambling. In 1594 imprisoned Catholic priests at Wisbech kept a traditional Christmas which included a hobby horse and morris dancing, and throughout the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Benedictine school at Douai retained the traditional festivities, complete with an elected 'Christmas King'. The Elizabethan Jesuit, John Gerard, relates in his autobiography how their vigorous celebration of Christmas and other feasts made Catholics particularly conspicuous at those times and, writing on the eve of the Civil War Richard Carpenter, a convert from Catholicism to Protestantism, observed that the recusant gentry were noted for their 'great Christmasses'. As a result, by the 1640s many English Protestants viewed Christmas festivities as the trappings of popery, anti-Christian 'rags of the Beast'.

The celebration of Christmas thus became just one facet of a deep religious cleavage within early seventeenth-century England which, by the middle of the century, was to lead to the breakdown of government, civil war and revolution. When the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made a concerted effort to abolish the Christian festival of Christmas and to outlaw the customs associated with it but the attempt foundered on the deep-rooted popular attachment to these mid-winter rites.

The controversy over how Christmas should be celebrated in London and the other Parliamentary centres surfaced in the early stages of the Civil War. In December 1642 Thomas .Fuller remarked, in a fast sermon delivered on Holy Innocents Day, that 'on this day a fast and feast do both justle together, and the question is which should take place in our affections'. While admitting that the young might be 'so addicted to their toys and Christmas sports that they will not be weaned from them', he advised the older generation among his listeners not to be 'transported with their follies, but mourn while they are in mirth'. The following December the issue led to violence in London when a crowd of apprentices attacked a number of shops in Cheapside which had opened for trading on Christmas Day and forced their owners, 'diverse holy Londoners', to close them. In reporting the incident Mercurius Civicus sympathised with the shopkeepers but argued that to avoid 'disturbance and uproars in the City' they should have waited 'till such time as a course shall be taken by lawful authority with matters of that nature'.

The following year, when Christmas Day fell on the last Wednesday in the month, the day set aside for a regular monthly fast, Parliament produced the anticipated legal rulings. On December 19th an ordinance was passed directing that the fast day should be observed in the normal way, but:

With the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance

our sins, and the sins of our forefathers who have turned this Feast,

pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him,

by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights...

Both Houses of Parliament attended fast sermons delivered by Presbyterian ministers on December 25th, 1644, the Commons hearing from Thomas Thorowgood that:

The providence of heaven is here become a Moderator appointing the

highest festival of all the year to meet with our monthly fast and be

ubdued by it.

In January 1645 the newly-published Directory of Public Worship, which outlined the basis of the new Presbyterian church establishment, affirmed bluntly that 'Festival days, vulgarly called Holy days, having no Warrant in the Word of God, are not to be continued'.

From 1646 onwards, with Parliament victorious over Charles I, the attack on the old church festivals intensified; as the Royalist author of the ballad The World is Turned Upside Down put it, 'Christmas was killed at Naseby fight'. In June 1647, a further Parliamentary ordinance abolished the feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun, and substituted as a regular holiday for students, servants and apprentices, the second Tuesday of every month. During the Christmas of 1647a number of ministers were taken into custody by the authorities for attempting to preach on Christmas Day, and one of them subsequently published his intended sermon under the title The Stillborn Nativity. Despite this government pressure, however, Christmas festivities remained popular, and successive regimes throughout the 1650s felt obliged to reiterate their objection to any observance of the feast.

In December 1650 the republican council of state urged the Rump of the Long Parliament to consider increasing the penalties for those caught attending 'those old superstitious obbservations', and in 1652 a proclamation published on Christmas Eve ordered that shops should be open and the markets kept on 25th, and that shopkeepers should be protected from violence or intimidation. Four years later, sitting on Christmas Day 1656, Oliver Cromwell's second Protectorate Parliament discussed a bill to prevent the celebrations in London. In 1657 the Council of State again urged the mayor and aldermen of London to clamp down on all celebrations in the capital, and a number of people attending church services on December 25th were held in custody and questioned by the army. Richard Cromwell's council repeated the injunctions to the mayor in December 1658. Insistent Puritan pressure, therefore, for the abolition of Christmas was kept up to within a few months of their fall from power at the Restoration, but it is clear even from the constant repetition of the government injunctions that it met with anything but willing acquiesence. In fact, the attack on Christmas produced instead a heated literary controversy and active, and on occasions violent measures to protect the traditional customs associated with the feast.

The debate as to whether Christmas should continue to be observed in the traditional manner was carried on in a series of rival works which appeared in the 1640s and 1650s, and which argued the case for both an educated and for a more popular audience. The intellectual debate began in 1644 with the appearance of the tract The Feast of Feasts, written by the Royalist clergyman Edward Fisher, and published in Oxford, the King's headquarters. This work introduced several of the main issues in the subsequent debate; whether the secular authorities had the right to legislate over the observance of church festivals and whether it could be proved that Jesus was born on December 25th. Fisher claimed that those who refused to recognise Christmas had 'revolted from the Church of Christ' and 'disgrace, hate, slander and persecute the most orthodox most eminent and chiefest of all the Reformed Churches, the Church of England'. He marshalled detailed scriptual and historical arguments to prove that the exact format of festivals was 'a thing indifferent' and thus within the power of civil government to organise. Dismissing all alternative datings of Christ's nativity, he asserted that 'the 25th day of December is the just, true and exact day of our Saviour's birth', and concluded with an exhortation to his readers to:

Stand fast and hold the traditions which we have been taught,

let us make them known to our children that the generations to come

may know them.

Several years later, with Charles I defeated and the attack on Christmas mounting, Fisher found support for his position from the author of A Ha! Christmas and from George Palmer's The Lawfulness of the Celebration of Christ's Birthday Debated. The first of these works, published in December 1647, emphasised the charitable aspect of Christmas, arguing that:

At such time as Christmas, those who God Almighty hath given a good

share of the wealth of this world may wear the best, eat and drink

the best with moderation, so that they remember Christ's poor members

with mercy and charity, and this year requireth more charity than

ordinary because of the dearness of provision of corn and victuals.

Palmer, a Canterbury cleric, published his detailed arguments in favour of celebration in the following December. He claimed that the exact date of Christ's birthday was 'no great matter... so as we do solemnize one day thankfully so near the true day we can guess', and dismissed objections grounded on the Catholic origins of Christmas, arguing that 'the first Popes were such as did accompany us in the way to salvation and were not so bad as in latter times they have been, and are now'. Writing in May 1648, with the knowledge that riots in Canterbury the previous Christmas had by then developed into a full scale Royalist uprising in Kent, Palmer also warned Parliament that their continued opposition to Christmas might create further resentment which its enemies could harness 'as a fair cloak to put on for to begin a quarrell, and so to incite some better men to take part with them'.

The counter-attack upon these opinions began the same month with the publication of Christs Birth Mistimed by Robert Skinner, and of Certain Queries Touching the Rise and Observation of Christmas by Joseph Hemming, a Presbyterian minister in Staffordshire. Hemming presented sixteen questions or 'queries', which attacked Christmas on the grounds that the date of Christ's birth was uncertain, that the feast had no scriptural basis but was purely a human invention, and that it was a superstitious relic of popery. He argued that Christmas had begun as a Christian version of the Roman mid-winter feast of the Saturnalia and that customs such as Yule games and carols were relics of these pagan rites. The following November this point was repeated in greater detail by Thomas Mockett, rector of Gilston in Hertfordshire, in his work Christmas, The Christians Grand Feast. In order to encourage the citizens of ancient Rome to convert, argued Mockett, the early Christians came up with their own equivalent of the Saturnalia, thus bringing:

...all the heathenish customs and pagan rites and ceremonies that the

idolatrous heathens used, as riotous drinking, health drinking, gluttony,

luxury, wantonness, dancing, dicing, stage-plays, interludes, masks,

mummeries, with all other pagan sports and profane practices into the

Church of God.

The appearance of Hemming's queries prompted Edward Fisher to re-enter the literary contest. In January 1649 he re-published The Feast of Feasts under a new title A Christian Caveat to the Old and New Sabbatarians, and appended to it a new point-by-point refutation of Hemming. He defended Yule sports with the claim 'the body is God's as well as the spirit and therefore why should not God be glorified by showing forth the strength, quickness and agility of our body' and denounced his adversaries for viewing it as superstitious:

To eat mince pies, plum-pottage or brawn in December, to trim churches

or private houses with holly and ivy about Christmas, to stick roasting

pieces of beef with rosemary or to stick a sprig of rosemary in a collar

of brawn, to play cards or bowls, to hawk or hunt, to give money

to the servants or apprentices box, or to send a couple of capons

or any other presents to a friend in the twelve days.

Fisher's arguments were clearly very popular; some 6,000 copies of A Christian Caveat were sold in the early 1650s, and by the end of the decade the work had been reissued five times.

Other titles, adding further weight to the arguments for celebration, appeared in the 1650s; these included Allan Blayney's Festorum Metropolis, first published in August 1652 and reissued in January 1654, and Henry Hammond's A Letter of Resolution To Six Queries of Present Use in the Church of England, which appeared in November 1652. Both claimed that Christmas rituals should be seen as desirable visual symbols which encouraged devotion among the illiterate. These works were in turn countered for the abolitionists by John Collings, a Presbyterian preacher from Norwich, in his Responsoria ad Erratica Piscatoris published in February 1653; by Ezekial Woodward, the minister of Bray in Berkshire in Christmas Day the Old Heathen's Feasting Day published in February 1656; and by Giles Collier, minister of Blockley in Worcestershire, in an appendix to his Vindiciae Thesium de Sabbato, which appeared in August 1656.

In addition to these contributions to the learned debate, the same period saw the publication of other material clearly intended to appeal to the illiterate or semi-literate mass of the population in London and elsewhere. January 1646 saw the appearance of the satire The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas, which claimed to have been printed by 'Simon Minced-Pie for Cicely Plum Pottage'. It took the form of a discussion between a London town crier and a Royalist gentlewoman who was enquiring after Father Christmas' whereabouts. The crier tells the lady that before the war Christmas:

Had looked under the consecrated lawn sleeve as big as Bull beef,

just like Bacchus upon a tun of wine when the grapes hung shaking

about his ears; but since the Catholic liquor is taken from him he is

much wasted.

He admits that he had been popular with apprentices, servants and scholars and that 'wanton women dote after him' but informs her that he is now 'constrained to remain in the Popish quarters'. The woman replies that:

If ever the Catholics or bishops rule again in England they will set the

church doors open on Christmas Day, and we shall have mass at the

High Altar as was used when the day was first instituted, and not have the holy Eucharist barred out of school, as school boys do their masters against the festival. What, shall we have our mouths shut to welcome old Christmas. No, no, bid him come by night over the Thames and we will have a bark door open to let him in.

I will myself give him his diet for one year to try his fortune, this time

twelve months may prove better.

Several months later appeared The Complaint of Christmas written by the satirical Royalist poet, John Taylor. It related the story of Father Christmas' visit the previous December to the 'schismatical and rebellious' towns of London, Yarmouth, Newbury and Gloucester, where he had found:

... no sign or token of any Holy Day. The shops were open, the markets

were full, the watermen rowing, the carmen were a loading and

unloading, the porters were bearing, and all Trades were forbearing

to keep any respective memory of me or Christ...

Enquiring of a cobbler what had happened, he was told 'it was a pity ever Christmas was born, and that I was a papist and idolatrous Brat of the Beast, an old reveller sent from Rome into England'. Travelling on into the rural districts he found an old parson 'reduced to look like a skeleton' who informed him that 'many mad seduced people have madly risen against God and the king', and he was later accosted by a large crowd of tradesmen, apprentices and servants complaining that:

All the liberty and harmless sports, with the merry gambols, dances and

friscals [by] which the toiling plowswain and labourer were wont to be

recreated and their spirits and hopes revived for a whole twelve month

are now extinct and put out of use in such a fashion as if they never had

been. Thus are the merry lords of misrule suppressed by the mad lords

of bad rule at Westminster.

Taylor's Father Christmas beats a hasty retreat from England, hoping to return to find 'better entertainment' the next year.

Taylor continued his Royalist propaganda campaign in favour of Christmas several years later, publishing two titles in December 1652, Christmas In and Out and The Vindication of Christmas, their contents being extremely similar and large passages appearing in both. Father Christmas again visits England to find it in a miserable condition and the people complaining 'that Mr. Tax and Mr. Plunder had played a game at sweep stake among them'. He speaks to a London merchant 'a fox-furred Mammonist' who taunts him doth thou see anyone that hath an ear to live and thrive in the world to be so mad as to mind thee', When he complains about the weakness of the beer offered him, which 'warmed a man's heart like pangs of death in a frosty morning', he is told:

Alas, father Christmas, our high and mighty ale that would formerly

knock down Hercules and trip up the heels of a Giant is lately struck

in a deep consumption, the strength of it being quite gone with a blow

from Westminster, and there is a Tetter and Ringworm called Excise

doth make it look thinner than it would do.

In Devon, however, he encounters some 'country farmers' who make him far more welcome and celebrate Christmas in the traditional fashion; together they:

Discoursed merely without either profaneness or obscenity.

Some went to cards, others sung carols and pleasant songs...

the poor labouring hinds and maid servants with the ploughboys

went nimbly dancing; the poor toiling wretches being glad of my

company because they had little or no sport at all till I came

amongst them...

He leaves exhorting them to 'call home exiles, help the fatherless, cherish the widow, and restore every man his due'.

Another similar piece, Women Will Have Their Will or Give Christmas His Due, which appeared in December 1648, seems to have been aimed particularly at a female audience. It contained a dialogue between 'Mistress Custom', a victualler's wife in Cripplegate and 'Mistress New-Come' an army captain's wife 'living in Reformation Alley near destruction street'. New-Come finds Custom decorating her house for Christmas and they fall into a discussion about the feast. Custom exclaims that:

I should rather and sooner forget my mother that bare me and the paps

that gave me suck, than forget this merry time, nay if thou had'st ever

seen the mirth and jollity that we have had at those times when I was young, thou wouldst bless thyself to see it.

She claims that those who want to destroy Christmas are:

A crew of Tatter-demallions amongst which the best could scarce ever

attain to a calves-skin suit, or a piece of neckbeef and carrots on a

Sunday, or scarce ever mounted (before these times) to any office above the degree of scavenger of Tithingman at the furthest.

When New-Come suggests she should abandon her celebrations because they have been banned by the authority of Parliament, she replies:

...God deliver me from such authority; it is a Worser Authority than

my husband's, for though my husband beats me now and then,

yet he gives my belly full and allows me money in my purse...

Cannot I keep Christmas, eat good cheer and be merry without I go

and get a licence from the Parliament. Marry gap, come up here,

for my part I'll be hanged by the neck first.

Mistress New-Come then informs her that if she disregards Parliament, she will be tamed by 'the honest Godly part of the army', but Custom ignores this threat, dismissing her with the rhyme:

For as long as I do live

And have a jovial crew

I'll sit and rhat, and be Fat

And give Christmas his due.

These pro-Christmas royalist satires, which could themselves be easily and effectively recited in taverns and market places, were complemented by a number of popular songs and ballads in defence of the feast, and by regular references to Christmas in the widely-read newsbooks of the day. Reporting the closure of the London churches on Christmas Day 1643, the Royalist Mercurius Aulicus asked 'whither will this mad faction run at last', and in 1645 Mercurius Academicus claimed that the Parliamentary soldiers in Abingdon had been forced to work on 25th December 'to keep wood cheap in forbearing Christmas fires'. In 1647 Mercurius Pragmatius included a Christmas rhyme which ended:

Christmas, farewell, thy Day, I fear

And merry days are done

So they may keep Feasts all the year

Our Saviour shall have none.

And in 1649 Mercurius Melancholius reported a rumour that the army and Parliament intended to bring Charles I to trial on Christmas Day, commenting:

When they should have been at church praying God for that memorable

and unspeakable merry which he that day showed to mankind

in sending his only begotten son into the world for their salvation,

they were practising an accusation against His deputy here on earth.

Response from the Parliamentary newsbooks was muted and sporadic; in 1643 The Scottish Dove concluded a lengthy discussion of Christmas festivities with the advice:

Every Christian is bound so far as the celebration of Christ's nativity

or the other festival days are idolatrous or heathenish to endeavour

to have them purged.

The following December The Kingdom's Weekly Intelligencer defended the Parliamentary attack on the feast with the challenge:

If there be any man that reads this that have seen an Inns of Court

or a temple Christmas, speak your conscience, if you not think it was

a place like Hell itself and that God is with those that would reform

such abuses.

In December 1645 Mercurius Civicus included the standard Parliamentary case against observation in its issue for the week preceding Christmas, but thereafter Parliamentary comment is largely restricted to accounts of violations of the government's orders by those determined to celebrate the feast, The scale and variety of the polemical literature about Christmas during these years suggests that Parliamentary attempts to eradicate the festival aroused strong emotions. This impression is confirmed when we consider the more direct evidence of the responses and reactions of individuals and communities to this frontal assault upon some of their most abiding traditions. What then becomes abundantly clear is that the attack on Christmas was viewed with a sense of regret and unease by many in the country irrespective of their social rank. In 1644 The Parliament Scout admitted that 'the alteration of this day troubles the children and servants who are afraid the time will be engrossed by the Father and Master before theirs to play in', and several years later Charles I expressed his own deep anxiety at the abolition of church feasts to his Parliamentary captors. The experiences of the Essex Presbyterian minister Ralph Josselin were probably very typical. In 1639, as a newly-ordained curate, he had preached at Deane, but on December 22nd, 1643, he wrote in his diary:

I made a serious exhortation to lay aside the jollity and vanity of the

time that custom hath wedded us into.

By 1647 he believed he had 'weaned' many of his parishioners from their previous practices, but confessed that 'people hanker after sports and pastimes that they were wonted to enjoy'.

Many therefore simply defied the government, and despite the pressures and intimidation, refused to abandon their traditional practices. Ignoring the official closure of the churches, where and when they could congregations still gathered together on December 25th to celebrate Christ's nativity. In 1647 Parliament instructed its committee for plundered ministers to take action against 'diverse ministers' who had held Christmas Day services, and a number of churchwardens were subsequently imprisoned for allowing them to take place. The Anglican diarist John Evelyn could find no Christmas services to attend in 1652 or 1655, but in 1657 he joined a 'grand assembly' which celebrated the birth of Christ in Exeter House chapel in the Strand. Along with others in the congregation, he was afterwards arrested and held for questioning for some time by the army. Other services took place the same day in Fleet Street and at Garlick Hill where, according to an army report, those involved included 'some old choristers and new taught singing boys' and where 'all the people bowed and cringed as if there had been mass'.

Far less effective was Parliament's attempt to abolish the traditional holiday over the Christmas period. The Moderate Intelligencer reported in December 1645 that hardly any shops were open in London on Christmas Day, and following month The True Informer explained its failure to appear during Christmas week as a 'necessitous compliance with the temper and disposition of the vulgar who... would either have refused to buy or vend anything which is not absolutely necessary, or else would not be at leisure to look after intelligence, being wholly taken up with recreation'. On December 27th, 1650, Sir Henry Mildmay reported to the House of Commons that on the 25th there had been:

...very wilful and strict observation of the day commonly called

Christmas Day throughout the cities of London and Westminster,

by a general keeping of their shops shut up and that there were

contemptuous speeches used by some in favour thereof.

Several newsbooks reported a similar complete closure in London in 1652, and on Christmas Day 1656 one MP remarked that 'one may pass from the Tower to Westminster and not a shop open, nor a creature stirring'.

With the churches and shops closed, the populace resorted to its traditional pastimes. In 1652 The Flying Eagle informed its readers that the 'taverns and taphouses' were full on Christmas Day, 'Bacchus bearing the bell amongst the people as if neither custom or excise were any burden to them', and claimed that 'the poor will pawn all to the clothes of their back to provide Christmas pies for their bellies and the broth of abominable things in their vessels, though they starve or pine for it all the year after'. In 1654 The Weekly Post reported the decoration of churches and rosemary and bays, and Francis Throckmorton, a student in Puritan Cambridge, paid 6d. for music and gave Christmas boxes to his servant, tailor and shoemaker. Three years later he spent Christmas at a country house in Worcestershire, where he exchanged presents and gave money to musicians and mummers. The same year John Evelyn invited in his neighbours after Christmas 'according to custom'.

In February 1656 Ezekial Woodward had to admit that 'the people go on holding fast to their heathenish customs and abominable idolatries, and think they do well'. The same fact was also obvious to those few MPs who attended the Commons on Christmas Day 1656. One complained that he had been disturbed the whole of the previous night by the preparations for 'this foolish day's solemnity', and John Lambert warned them that, as he spoke, the Royalists would be 'merry over their Christmas pies, drinking the King of Scots health, or your confusion'.

Particularly distressing for the MPs was the knowledge that disagreements over the observance of Christmas could lead to violence and civil disorder, and had on one occasion been the prelude to a full-scale Royalist uprising. In London on Christmas Day 1643 a mob of apprentices forced the closure of any shops which had opened for business. Four years later there was more trouble when a large crowd of Londoners gathered to prevent the mayor and his marshalls removing the Christmas decorations which some of the city porters had draped around the conduit in Cornhill. The confrontation ended in uproar, with arrests, injuries, and the bolting of the mayor's frightened horse. The Royalist newsbook Mercurius Elenticus claimed that one man subsequently died of his injuries in Newgate jail.

Nor was trouble confined to the capital. On Christmas Day 1646 at Bury St Edmunds a crowd of apprentices met together to prevent tradesmen opening for business. When the local magistrate and constables told them to disperse or risk imprisonment, a scuffle broke out and several people were injured. Far more serious incidents occurred the following December when, according to The Kingdom's Weekly Post, on Christmas Day:

... in some places in the country so eager were they of a sermon...

by such as they approved of that the church doors were kept with

swords and other weapons defensive and offensive whilst the

minister was in the pulpit.

In Norwich the weeks leading up to Christmas 1647 saw bitter in-fighting between the Puritan preachers, who petitioned the mayor for a 'more speedy and thorough reformation', and the apprentices who counter-petitioned that Christmas festivities should be permitted. Further south in Ipswich, those who wanted to observe Christmas took part in a 'great mutiny', and when their leaders were arrested they attempted to rescue them by force. In the resulting melee one eponymous rioter called Christmas 'whose name seemed to blow up the coals of his zeal to the observation of the day', was killed.

The most serious trouble, however, occurred in Canterbury where, in response to an order of the county committee outlawing Christmas celebrations, a large crowd gathered on Christmas Bay to demand a church service and ensure that shops remained shut. Fights again developed, a soldier was assaulted, and the mayor's house attacked. For several weeks the rioters controlled the city; they decorated doorways with holly bushes and, ominously for the government, adopted the slogan 'For God, King Charles, and Kent'. They were forced to surrender in early January but within six months large areas of Kent were involved in the second Civil War, a full-scale insurrection in support of Charles I. So too were some of the inhabitants of Norwich and Bury, also previous centres of pro-Christmas demonstrations. By the late 1640s, therefore, the Puritan equation of Christmas with Royalism had become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Traditional Christmas festivities duly returned to England with Charles II in 1660, and while the Restoration's association with maypoles and 'Merry England' may have been overstated in the past, there is no doubt that most English people were very glad that their Christmas celebrations were once more acceptable. According to The Kingdom's Intelligencer, at Maidstone in Kent, where there had been no Christmas Day services for seventeen years, on December 25th, 1660, several sermons were preached and communion administered, 'to the joy of many hundred Christians'. On the Sunday before Christmas, Samuel Pepys' church in London was decorated with rosemary and bays; on the 25th Pepys attended morning service and returned home to a Christmas dinner of shoulder of mutton and chicken. Predictably, he slept through the afternoon sermon, but he had revived sufficiently by the evening to read and play his lute. The Buckinghamshire gentry family, the Verneys, resumed their celebrations on a grand scale; in 1664 a family friend wrote that:

... the news at Buckingham is that you will keep the best Christmas

in the shire, and to that end have bought more fruit and spice than half

the porters in London can weigh out in a day.

Perhaps even the Puritan minister Ralph Josselin was secretly relieved; by 1662 he was again preaching on Christmas Day, and on December 25th, 1667, he wrote in his diary:

Preached and feasted my tenants and all my children with joy.

Lord sanctify.

The revolt against Charles I in the 1640s was led originally by men who believed that his government was determined to outlaw their traditional Calvinist religious beliefs and eventually to reunite the Church of England with Rome. The events of the Civil War soon brought to prominence among the Parliamentarians many Puritans whose psychological makeup made them suspicious of geniality, contemptuous of excess and paranoid about the anarchic potential of carnival. It was these men who launched the attack on the traditional Christian festivals of the English calendar. However, by perceiving these essentially harmless and deeply cherished folk customs to be a threat, they succeeded only in alienating large numbers from the new regime they had established. John Morrill has recently pointed out that the Parliamentary colonel John Lambert came to see the English people's persistent attachment to Christmas as a symbol of their refusal to accept his revolution. Much the same view was expressed by one contemporary Parliamentary pamphleteer who reported that the Royalists 'cry unto the people':

What, pull down common-prayer, plum pottage and Whitsun ales;

Was there ever such a sacrilege and profaneness. Rather than so,

come along to battle.

They admitted that 'grand festivals and lesser holy-days... are the main things which the more ignorant and common sort among them do fight for'. The attack on Christmas was thus one of the Parliamentarians' biggest mistakes, and one which was ironically the result of anxieties, originally misconceived but ultimately self-fulfilling.

Further Reading:

- John Morrill, Reactions to English Civil War (Macmillan, 1982) and England's Wars of Religion (forthcoming)

- John Bossy, Christianity in the West (Opus, 1985)

- William Hunt, The Puritan Movement (Harvard, 1983)

- Christopher Hill, Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England (Panther, 1969)

- Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971)

- Peter Clark and Paul Slack, Crisis and Order in English Towns 1500-1700 (Opus, 1976).

Chris Durston is senior lecturer in history at St Mary's, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham.

Such long-cherished activities necessarily often led to drunkenness, promiscuity and other forms of excess. In fact the concept of 'misrule', or a ritualised reversal of traditional social norms, was an important element of Christmas, and has been viewed by historians as a useful safety-valve for the tensions within English society. It was precisely this face of Christmas, however, that the Puritans of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England found so objectionable. In the 1580s, Philip Stubbes, the author of The Anatomie of Abuses, complained:

That more mischief is that time committed than in all the year besides,

what masking and mumming, whereby robbery whoredom, murder

and what not is committed? What dicing and carding, what eating and

drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used, more than in all

the year besides, to the great dishonour of God and impoverishing of the

realm.

In addition to this association with immorality and the concept of misrule, another of the central objections to the feast for the stricter English Protestants between 1560 and 1640 was its popularity among the papist recusant community. Within the late medieval Catholic church, Christmas had taken a subordinate position in the liturgical calendar to Easter. Its importance, however, had been growing and was further enhanced by the religious conflicts of the sixteenth century, for whereas, as John Bossy has recently pointed out, the more extreme Protestants had little time fox Christ's 'holy family', reformed Catholicism laid great stress on this area. The Tridentine emphasis on devotions to the Virgin Mary in particular elevated the status of the feast during which she was portrayed as a paragon of motherhood.

Certainly, English recusants seem to have retained a deep attachment to Christmas during Elizabeth I's reign and the early part of the seventeenth century. The staunchly Catholic gentlewoman, Dorothy Lawson, celebrated Christmas 'in both kinds... corporally and spiritually', indulging in Christmas pies, dancing and gambling. In 1594 imprisoned Catholic priests at Wisbech kept a traditional Christmas which included a hobby horse and morris dancing, and throughout the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Benedictine school at Douai retained the traditional festivities, complete with an elected 'Christmas King'. The Elizabethan Jesuit, John Gerard, relates in his autobiography how their vigorous celebration of Christmas and other feasts made Catholics particularly conspicuous at those times and, writing on the eve of the Civil War Richard Carpenter, a convert from Catholicism to Protestantism, observed that the recusant gentry were noted for their 'great Christmasses'. As a result, by the 1640s many English Protestants viewed Christmas festivities as the trappings of popery, anti-Christian 'rags of the Beast'.

The celebration of Christmas thus became just one facet of a deep religious cleavage within early seventeenth-century England which, by the middle of the century, was to lead to the breakdown of government, civil war and revolution. When the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made a concerted effort to abolish the Christian festival of Christmas and to outlaw the customs associated with it but the attempt foundered on the deep-rooted popular attachment to these mid-winter rites.

The controversy over how Christmas should be celebrated in London and the other Parliamentary centres surfaced in the early stages of the Civil War. In December 1642 Thomas .Fuller remarked, in a fast sermon delivered on Holy Innocents Day, that 'on this day a fast and feast do both justle together, and the question is which should take place in our affections'. While admitting that the young might be 'so addicted to their toys and Christmas sports that they will not be weaned from them', he advised the older generation among his listeners not to be 'transported with their follies, but mourn while they are in mirth'. The following December the issue led to violence in London when a crowd of apprentices attacked a number of shops in Cheapside which had opened for trading on Christmas Day and forced their owners, 'diverse holy Londoners', to close them. In reporting the incident Mercurius Civicus sympathised with the shopkeepers but argued that to avoid 'disturbance and uproars in the City' they should have waited 'till such time as a course shall be taken by lawful authority with matters of that nature'.

The following year, when Christmas Day fell on the last Wednesday in the month, the day set aside for a regular monthly fast, Parliament produced the anticipated legal rulings. On December 19th an ordinance was passed directing that the fast day should be observed in the normal way, but:

The controversy over how Christmas should be celebrated in London and the other Parliamentary centres surfaced in the early stages of the Civil War. In December 1642 Thomas .Fuller remarked, in a fast sermon delivered on Holy Innocents Day, that 'on this day a fast and feast do both justle together, and the question is which should take place in our affections'. While admitting that the young might be 'so addicted to their toys and Christmas sports that they will not be weaned from them', he advised the older generation among his listeners not to be 'transported with their follies, but mourn while they are in mirth'. The following December the issue led to violence in London when a crowd of apprentices attacked a number of shops in Cheapside which had opened for trading on Christmas Day and forced their owners, 'diverse holy Londoners', to close them. In reporting the incident Mercurius Civicus sympathised with the shopkeepers but argued that to avoid 'disturbance and uproars in the City' they should have waited 'till such time as a course shall be taken by lawful authority with matters of that nature'.

The following year, when Christmas Day fell on the last Wednesday in the month, the day set aside for a regular monthly fast, Parliament produced the anticipated legal rulings. On December 19th an ordinance was passed directing that the fast day should be observed in the normal way, but:

With the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance

our sins, and the sins of our forefathers who have turned this Feast,

pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him,

by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights...

Both Houses of Parliament attended fast sermons delivered by Presbyterian ministers on December 25th, 1644, the Commons hearing from Thomas Thorowgood that:

The providence of heaven is here become a Moderator appointing the

highest festival of all the year to meet with our monthly fast and be

ubdued by it.

In January 1645 the newly-published Directory of Public Worship, which outlined the basis of the new Presbyterian church establishment, affirmed bluntly that 'Festival days, vulgarly called Holy days, having no Warrant in the Word of God, are not to be continued'.

From 1646 onwards, with Parliament victorious over Charles I, the attack on the old church festivals intensified; as the Royalist author of the ballad The World is Turned Upside Down put it, 'Christmas was killed at Naseby fight'. In June 1647, a further Parliamentary ordinance abolished the feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun, and substituted as a regular holiday for students, servants and apprentices, the second Tuesday of every month. During the Christmas of 1647a number of ministers were taken into custody by the authorities for attempting to preach on Christmas Day, and one of them subsequently published his intended sermon under the title The Stillborn Nativity. Despite this government pressure, however, Christmas festivities remained popular, and successive regimes throughout the 1650s felt obliged to reiterate their objection to any observance of the feast.

In December 1650 the republican council of state urged the Rump of the Long Parliament to consider increasing the penalties for those caught attending 'those old superstitious obbservations', and in 1652 a proclamation published on Christmas Eve ordered that shops should be open and the markets kept on 25th, and that shopkeepers should be protected from violence or intimidation. Four years later, sitting on Christmas Day 1656, Oliver Cromwell's second Protectorate Parliament discussed a bill to prevent the celebrations in London. In 1657 the Council of State again urged the mayor and aldermen of London to clamp down on all celebrations in the capital, and a number of people attending church services on December 25th were held in custody and questioned by the army. Richard Cromwell's council repeated the injunctions to the mayor in December 1658. Insistent Puritan pressure, therefore, for the abolition of Christmas was kept up to within a few months of their fall from power at the Restoration, but it is clear even from the constant repetition of the government injunctions that it met with anything but willing acquiesence. In fact, the attack on Christmas produced instead a heated literary controversy and active, and on occasions violent measures to protect the traditional customs associated with the feast.

The debate as to whether Christmas should continue to be observed in the traditional manner was carried on in a series of rival works which appeared in the 1640s and 1650s, and which argued the case for both an educated and for a more popular audience. The intellectual debate began in 1644 with the appearance of the tract The Feast of Feasts, written by the Royalist clergyman Edward Fisher, and published in Oxford, the King's headquarters. This work introduced several of the main issues in the subsequent debate; whether the secular authorities had the right to legislate over the observance of church festivals and whether it could be proved that Jesus was born on December 25th. Fisher claimed that those who refused to recognise Christmas had 'revolted from the Church of Christ' and 'disgrace, hate, slander and persecute the most orthodox most eminent and chiefest of all the Reformed Churches, the Church of England'. He marshalled detailed scriptual and historical arguments to prove that the exact format of festivals was 'a thing indifferent' and thus within the power of civil government to organise. Dismissing all alternative datings of Christ's nativity, he asserted that 'the 25th day of December is the just, true and exact day of our Saviour's birth', and concluded with an exhortation to his readers to:

Stand fast and hold the traditions which we have been taught,

let us make them known to our children that the generations to come

may know them.

Several years later, with Charles I defeated and the attack on Christmas mounting, Fisher found support for his position from the author of A Ha! Christmas and from George Palmer's The Lawfulness of the Celebration of Christ's Birthday Debated. The first of these works, published in December 1647, emphasised the charitable aspect of Christmas, arguing that:

At such time as Christmas, those who God Almighty hath given a good

share of the wealth of this world may wear the best, eat and drink

the best with moderation, so that they remember Christ's poor members

with mercy and charity, and this year requireth more charity than

ordinary because of the dearness of provision of corn and victuals.

Palmer, a Canterbury cleric, published his detailed arguments in favour of celebration in the following December. He claimed that the exact date of Christ's birthday was 'no great matter... so as we do solemnize one day thankfully so near the true day we can guess', and dismissed objections grounded on the Catholic origins of Christmas, arguing that 'the first Popes were such as did accompany us in the way to salvation and were not so bad as in latter times they have been, and are now'. Writing in May 1648, with the knowledge that riots in Canterbury the previous Christmas had by then developed into a full scale Royalist uprising in Kent, Palmer also warned Parliament that their continued opposition to Christmas might create further resentment which its enemies could harness 'as a fair cloak to put on for to begin a quarrell, and so to incite some better men to take part with them'.

The counter-attack upon these opinions began the same month with the publication of Christs Birth Mistimed by Robert Skinner, and of Certain Queries Touching the Rise and Observation of Christmas by Joseph Hemming, a Presbyterian minister in Staffordshire. Hemming presented sixteen questions or 'queries', which attacked Christmas on the grounds that the date of Christ's birth was uncertain, that the feast had no scriptural basis but was purely a human invention, and that it was a superstitious relic of popery. He argued that Christmas had begun as a Christian version of the Roman mid-winter feast of the Saturnalia and that customs such as Yule games and carols were relics of these pagan rites. The following November this point was repeated in greater detail by Thomas Mockett, rector of Gilston in Hertfordshire, in his work Christmas, The Christians Grand Feast. In order to encourage the citizens of ancient Rome to convert, argued Mockett, the early Christians came up with their own equivalent of the Saturnalia, thus bringing:

...all the heathenish customs and pagan rites and ceremonies that the

idolatrous heathens used, as riotous drinking, health drinking, gluttony,

luxury, wantonness, dancing, dicing, stage-plays, interludes, masks,

mummeries, with all other pagan sports and profane practices into the

Church of God.

The appearance of Hemming's queries prompted Edward Fisher to re-enter the literary contest. In January 1649 he re-published The Feast of Feasts under a new title A Christian Caveat to the Old and New Sabbatarians, and appended to it a new point-by-point refutation of Hemming. He defended Yule sports with the claim 'the body is God's as well as the spirit and therefore why should not God be glorified by showing forth the strength, quickness and agility of our body' and denounced his adversaries for viewing it as superstitious:

To eat mince pies, plum-pottage or brawn in December, to trim churches

or private houses with holly and ivy about Christmas, to stick roasting

pieces of beef with rosemary or to stick a sprig of rosemary in a collar

of brawn, to play cards or bowls, to hawk or hunt, to give money

to the servants or apprentices box, or to send a couple of capons

or any other presents to a friend in the twelve days.

Fisher's arguments were clearly very popular; some 6,000 copies of A Christian Caveat were sold in the early 1650s, and by the end of the decade the work had been reissued five times.

Other titles, adding further weight to the arguments for celebration, appeared in the 1650s; these included Allan Blayney's Festorum Metropolis, first published in August 1652 and reissued in January 1654, and Henry Hammond's A Letter of Resolution To Six Queries of Present Use in the Church of England, which appeared in November 1652. Both claimed that Christmas rituals should be seen as desirable visual symbols which encouraged devotion among the illiterate. These works were in turn countered for the abolitionists by John Collings, a Presbyterian preacher from Norwich, in his Responsoria ad Erratica Piscatoris published in February 1653; by Ezekial Woodward, the minister of Bray in Berkshire in Christmas Day the Old Heathen's Feasting Day published in February 1656; and by Giles Collier, minister of Blockley in Worcestershire, in an appendix to his Vindiciae Thesium de Sabbato, which appeared in August 1656.

In addition to these contributions to the learned debate, the same period saw the publication of other material clearly intended to appeal to the illiterate or semi-literate mass of the population in London and elsewhere. January 1646 saw the appearance of the satire The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas, which claimed to have been printed by 'Simon Minced-Pie for Cicely Plum Pottage'. It took the form of a discussion between a London town crier and a Royalist gentlewoman who was enquiring after Father Christmas' whereabouts. The crier tells the lady that before the war Christmas:

Had looked under the consecrated lawn sleeve as big as Bull beef,

just like Bacchus upon a tun of wine when the grapes hung shaking

about his ears; but since the Catholic liquor is taken from him he is

much wasted.

He admits that he had been popular with apprentices, servants and scholars and that 'wanton women dote after him' but informs her that he is now 'constrained to remain in the Popish quarters'. The woman replies that:

If ever the Catholics or bishops rule again in England they will set the

church doors open on Christmas Day, and we shall have mass at the

High Altar as was used when the day was first instituted, and not have the holy Eucharist barred out of school, as school boys do their masters against the festival. What, shall we have our mouths shut to welcome old Christmas. No, no, bid him come by night over the Thames and we will have a bark door open to let him in.

I will myself give him his diet for one year to try his fortune, this time

twelve months may prove better.

Several months later appeared The Complaint of Christmas written by the satirical Royalist poet, John Taylor. It related the story of Father Christmas' visit the previous December to the 'schismatical and rebellious' towns of London, Yarmouth, Newbury and Gloucester, where he had found:

... no sign or token of any Holy Day. The shops were open, the markets

were full, the watermen rowing, the carmen were a loading and

unloading, the porters were bearing, and all Trades were forbearing

to keep any respective memory of me or Christ...

Enquiring of a cobbler what had happened, he was told 'it was a pity ever Christmas was born, and that I was a papist and idolatrous Brat of the Beast, an old reveller sent from Rome into England'. Travelling on into the rural districts he found an old parson 'reduced to look like a skeleton' who informed him that 'many mad seduced people have madly risen against God and the king', and he was later accosted by a large crowd of tradesmen, apprentices and servants complaining that:

All the liberty and harmless sports, with the merry gambols, dances and

friscals [by] which the toiling plowswain and labourer were wont to be

recreated and their spirits and hopes revived for a whole twelve month

are now extinct and put out of use in such a fashion as if they never had

been. Thus are the merry lords of misrule suppressed by the mad lords

of bad rule at Westminster.

Taylor's Father Christmas beats a hasty retreat from England, hoping to return to find 'better entertainment' the next year.

Taylor continued his Royalist propaganda campaign in favour of Christmas several years later, publishing two titles in December 1652, Christmas In and Out and The Vindication of Christmas, their contents being extremely similar and large passages appearing in both. Father Christmas again visits England to find it in a miserable condition and the people complaining 'that Mr. Tax and Mr. Plunder had played a game at sweep stake among them'. He speaks to a London merchant 'a fox-furred Mammonist' who taunts him doth thou see anyone that hath an ear to live and thrive in the world to be so mad as to mind thee', When he complains about the weakness of the beer offered him, which 'warmed a man's heart like pangs of death in a frosty morning', he is told:

Alas, father Christmas, our high and mighty ale that would formerly

knock down Hercules and trip up the heels of a Giant is lately struck

in a deep consumption, the strength of it being quite gone with a blow

from Westminster, and there is a Tetter and Ringworm called Excise

doth make it look thinner than it would do.

In Devon, however, he encounters some 'country farmers' who make him far more welcome and celebrate Christmas in the traditional fashion; together they:

Discoursed merely without either profaneness or obscenity.

Some went to cards, others sung carols and pleasant songs...

the poor labouring hinds and maid servants with the ploughboys

went nimbly dancing; the poor toiling wretches being glad of my

company because they had little or no sport at all till I came

amongst them...

He leaves exhorting them to 'call home exiles, help the fatherless, cherish the widow, and restore every man his due'.

Another similar piece, Women Will Have Their Will or Give Christmas His Due, which appeared in December 1648, seems to have been aimed particularly at a female audience. It contained a dialogue between 'Mistress Custom', a victualler's wife in Cripplegate and 'Mistress New-Come' an army captain's wife 'living in Reformation Alley near destruction street'. New-Come finds Custom decorating her house for Christmas and they fall into a discussion about the feast. Custom exclaims that:

I should rather and sooner forget my mother that bare me and the paps

that gave me suck, than forget this merry time, nay if thou had'st ever

seen the mirth and jollity that we have had at those times when I was young, thou wouldst bless thyself to see it.

She claims that those who want to destroy Christmas are:

A crew of Tatter-demallions amongst which the best could scarce ever

attain to a calves-skin suit, or a piece of neckbeef and carrots on a

Sunday, or scarce ever mounted (before these times) to any office above the degree of scavenger of Tithingman at the furthest.

When New-Come suggests she should abandon her celebrations because they have been banned by the authority of Parliament, she replies:

...God deliver me from such authority; it is a Worser Authority than

my husband's, for though my husband beats me now and then,

yet he gives my belly full and allows me money in my purse...

Cannot I keep Christmas, eat good cheer and be merry without I go

and get a licence from the Parliament. Marry gap, come up here,

for my part I'll be hanged by the neck first.

Mistress New-Come then informs her that if she disregards Parliament, she will be tamed by 'the honest Godly part of the army', but Custom ignores this threat, dismissing her with the rhyme:

For as long as I do live

And have a jovial crew

I'll sit and rhat, and be Fat

And give Christmas his due.

These pro-Christmas royalist satires, which could themselves be easily and effectively recited in taverns and market places, were complemented by a number of popular songs and ballads in defence of the feast, and by regular references to Christmas in the widely-read newsbooks of the day. Reporting the closure of the London churches on Christmas Day 1643, the Royalist Mercurius Aulicus asked 'whither will this mad faction run at last', and in 1645 Mercurius Academicus claimed that the Parliamentary soldiers in Abingdon had been forced to work on 25th December 'to keep wood cheap in forbearing Christmas fires'. In 1647 Mercurius Pragmatius included a Christmas rhyme which ended:

Christmas, farewell, thy Day, I fear

And merry days are done

So they may keep Feasts all the year

Our Saviour shall have none.

And in 1649 Mercurius Melancholius reported a rumour that the army and Parliament intended to bring Charles I to trial on Christmas Day, commenting:

When they should have been at church praying God for that memorable

and unspeakable merry which he that day showed to mankind

in sending his only begotten son into the world for their salvation,

they were practising an accusation against His deputy here on earth.

Response from the Parliamentary newsbooks was muted and sporadic; in 1643 The Scottish Dove concluded a lengthy discussion of Christmas festivities with the advice:

Every Christian is bound so far as the celebration of Christ's nativity

or the other festival days are idolatrous or heathenish to endeavour

to have them purged.

The following December The Kingdom's Weekly Intelligencer defended the Parliamentary attack on the feast with the challenge:

If there be any man that reads this that have seen an Inns of Court

or a temple Christmas, speak your conscience, if you not think it was

a place like Hell itself and that God is with those that would reform

such abuses.

In December 1645 Mercurius Civicus included the standard Parliamentary case against observation in its issue for the week preceding Christmas, but thereafter Parliamentary comment is largely restricted to accounts of violations of the government's orders by those determined to celebrate the feast, The scale and variety of the polemical literature about Christmas during these years suggests that Parliamentary attempts to eradicate the festival aroused strong emotions. This impression is confirmed when we consider the more direct evidence of the responses and reactions of individuals and communities to this frontal assault upon some of their most abiding traditions. What then becomes abundantly clear is that the attack on Christmas was viewed with a sense of regret and unease by many in the country irrespective of their social rank. In 1644 The Parliament Scout admitted that 'the alteration of this day troubles the children and servants who are afraid the time will be engrossed by the Father and Master before theirs to play in', and several years later Charles I expressed his own deep anxiety at the abolition of church feasts to his Parliamentary captors. The experiences of the Essex Presbyterian minister Ralph Josselin were probably very typical. In 1639, as a newly-ordained curate, he had preached at Deane, but on December 22nd, 1643, he wrote in his diary:

I made a serious exhortation to lay aside the jollity and vanity of the

time that custom hath wedded us into.

By 1647 he believed he had 'weaned' many of his parishioners from their previous practices, but confessed that 'people hanker after sports and pastimes that they were wonted to enjoy'.

Many therefore simply defied the government, and despite the pressures and intimidation, refused to abandon their traditional practices. Ignoring the official closure of the churches, where and when they could congregations still gathered together on December 25th to celebrate Christ's nativity. In 1647 Parliament instructed its committee for plundered ministers to take action against 'diverse ministers' who had held Christmas Day services, and a number of churchwardens were subsequently imprisoned for allowing them to take place. The Anglican diarist John Evelyn could find no Christmas services to attend in 1652 or 1655, but in 1657 he joined a 'grand assembly' which celebrated the birth of Christ in Exeter House chapel in the Strand. Along with others in the congregation, he was afterwards arrested and held for questioning for some time by the army. Other services took place the same day in Fleet Street and at Garlick Hill where, according to an army report, those involved included 'some old choristers and new taught singing boys' and where 'all the people bowed and cringed as if there had been mass'.

Far less effective was Parliament's attempt to abolish the traditional holiday over the Christmas period. The Moderate Intelligencer reported in December 1645 that hardly any shops were open in London on Christmas Day, and following month The True Informer explained its failure to appear during Christmas week as a 'necessitous compliance with the temper and disposition of the vulgar who... would either have refused to buy or vend anything which is not absolutely necessary, or else would not be at leisure to look after intelligence, being wholly taken up with recreation'. On December 27th, 1650, Sir Henry Mildmay reported to the House of Commons that on the 25th there had been:

...very wilful and strict observation of the day commonly called

Christmas Day throughout the cities of London and Westminster,

by a general keeping of their shops shut up and that there were

contemptuous speeches used by some in favour thereof.

Several newsbooks reported a similar complete closure in London in 1652, and on Christmas Day 1656 one MP remarked that 'one may pass from the Tower to Westminster and not a shop open, nor a creature stirring'.

With the churches and shops closed, the populace resorted to its traditional pastimes. In 1652 The Flying Eagle informed its readers that the 'taverns and taphouses' were full on Christmas Day, 'Bacchus bearing the bell amongst the people as if neither custom or excise were any burden to them', and claimed that 'the poor will pawn all to the clothes of their back to provide Christmas pies for their bellies and the broth of abominable things in their vessels, though they starve or pine for it all the year after'. In 1654 The Weekly Post reported the decoration of churches and rosemary and bays, and Francis Throckmorton, a student in Puritan Cambridge, paid 6d. for music and gave Christmas boxes to his servant, tailor and shoemaker. Three years later he spent Christmas at a country house in Worcestershire, where he exchanged presents and gave money to musicians and mummers. The same year John Evelyn invited in his neighbours after Christmas 'according to custom'.

In February 1656 Ezekial Woodward had to admit that 'the people go on holding fast to their heathenish customs and abominable idolatries, and think they do well'. The same fact was also obvious to those few MPs who attended the Commons on Christmas Day 1656. One complained that he had been disturbed the whole of the previous night by the preparations for 'this foolish day's solemnity', and John Lambert warned them that, as he spoke, the Royalists would be 'merry over their Christmas pies, drinking the King of Scots health, or your confusion'.

Particularly distressing for the MPs was the knowledge that disagreements over the observance of Christmas could lead to violence and civil disorder, and had on one occasion been the prelude to a full-scale Royalist uprising. In London on Christmas Day 1643 a mob of apprentices forced the closure of any shops which had opened for business. Four years later there was more trouble when a large crowd of Londoners gathered to prevent the mayor and his marshalls removing the Christmas decorations which some of the city porters had draped around the conduit in Cornhill. The confrontation ended in uproar, with arrests, injuries, and the bolting of the mayor's frightened horse. The Royalist newsbook Mercurius Elenticus claimed that one man subsequently died of his injuries in Newgate jail.

Nor was trouble confined to the capital. On Christmas Day 1646 at Bury St Edmunds a crowd of apprentices met together to prevent tradesmen opening for business. When the local magistrate and constables told them to disperse or risk imprisonment, a scuffle broke out and several people were injured. Far more serious incidents occurred the following December when, according to The Kingdom's Weekly Post, on Christmas Day:

... in some places in the country so eager were they of a sermon...

by such as they approved of that the church doors were kept with

swords and other weapons defensive and offensive whilst the

minister was in the pulpit.

In Norwich the weeks leading up to Christmas 1647 saw bitter in-fighting between the Puritan preachers, who petitioned the mayor for a 'more speedy and thorough reformation', and the apprentices who counter-petitioned that Christmas festivities should be permitted. Further south in Ipswich, those who wanted to observe Christmas took part in a 'great mutiny', and when their leaders were arrested they attempted to rescue them by force. In the resulting melee one eponymous rioter called Christmas 'whose name seemed to blow up the coals of his zeal to the observation of the day', was killed.

The most serious trouble, however, occurred in Canterbury where, in response to an order of the county committee outlawing Christmas celebrations, a large crowd gathered on Christmas Bay to demand a church service and ensure that shops remained shut. Fights again developed, a soldier was assaulted, and the mayor's house attacked. For several weeks the rioters controlled the city; they decorated doorways with holly bushes and, ominously for the government, adopted the slogan 'For God, King Charles, and Kent'. They were forced to surrender in early January but within six months large areas of Kent were involved in the second Civil War, a full-scale insurrection in support of Charles I. So too were some of the inhabitants of Norwich and Bury, also previous centres of pro-Christmas demonstrations. By the late 1640s, therefore, the Puritan equation of Christmas with Royalism had become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Traditional Christmas festivities duly returned to England with Charles II in 1660, and while the Restoration's association with maypoles and 'Merry England' may have been overstated in the past, there is no doubt that most English people were very glad that their Christmas celebrations were once more acceptable. According to The Kingdom's Intelligencer, at Maidstone in Kent, where there had been no Christmas Day services for seventeen years, on December 25th, 1660, several sermons were preached and communion administered, 'to the joy of many hundred Christians'. On the Sunday before Christmas, Samuel Pepys' church in London was decorated with rosemary and bays; on the 25th Pepys attended morning service and returned home to a Christmas dinner of shoulder of mutton and chicken. Predictably, he slept through the afternoon sermon, but he had revived sufficiently by the evening to read and play his lute. The Buckinghamshire gentry family, the Verneys, resumed their celebrations on a grand scale; in 1664 a family friend wrote that:

... the news at Buckingham is that you will keep the best Christmas

in the shire, and to that end have bought more fruit and spice than half

the porters in London can weigh out in a day.

Perhaps even the Puritan minister Ralph Josselin was secretly relieved; by 1662 he was again preaching on Christmas Day, and on December 25th, 1667, he wrote in his diary:

Preached and feasted my tenants and all my children with joy.

Lord sanctify.

The revolt against Charles I in the 1640s was led originally by men who believed that his government was determined to outlaw their traditional Calvinist religious beliefs and eventually to reunite the Church of England with Rome. The events of the Civil War soon brought to prominence among the Parliamentarians many Puritans whose psychological makeup made them suspicious of geniality, contemptuous of excess and paranoid about the anarchic potential of carnival. It was these men who launched the attack on the traditional Christian festivals of the English calendar. However, by perceiving these essentially harmless and deeply cherished folk customs to be a threat, they succeeded only in alienating large numbers from the new regime they had established. John Morrill has recently pointed out that the Parliamentary colonel John Lambert came to see the English people's persistent attachment to Christmas as a symbol of their refusal to accept his revolution. Much the same view was expressed by one contemporary Parliamentary pamphleteer who reported that the Royalists 'cry unto the people':

What, pull down common-prayer, plum pottage and Whitsun ales;

Was there ever such a sacrilege and profaneness. Rather than so,

come along to battle.