Kremlin’s Move Against Wikipedia a Harbinger of Even Worse Ahead

Paul Goble

Window On Eurasia (Blog)

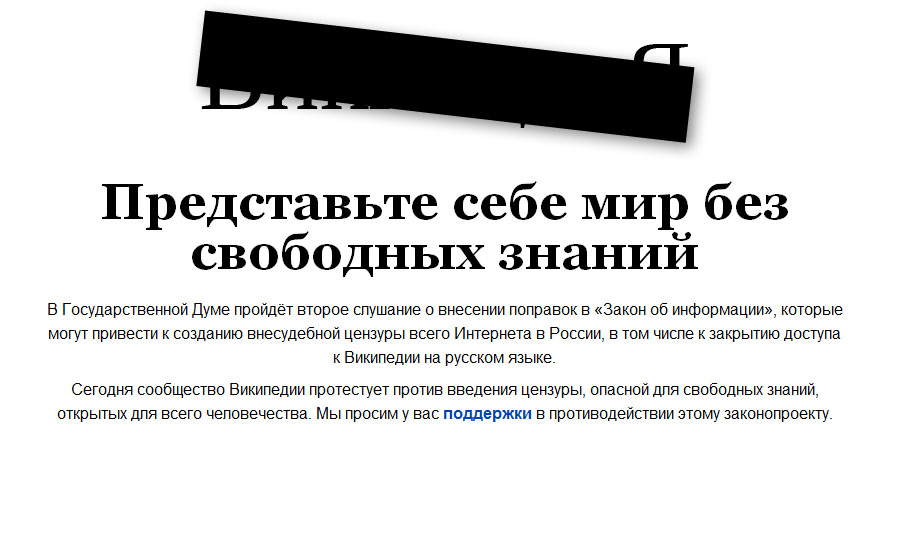

Staunton, August 25 – Russian officials said this morning that they had removed from the list of prohibited sites articles on Wikipedia about drugs after the editors of that site changed them following a Russian threat to block access to the entire Russian-language Wikipedia if the latter did not change them.

As a result, Moscow officials said, Russians now again have free access to the Russian-language of Wikipedia even though several hours earlier there were widespread reports that providers in some Russian regions were blocking the entire portal (echo.msk.ru/news/1609792-echo.html and grani.ru/Internet/m.243789.html).

If coverage of this event follows past practice, two things are almost certain. On the one hand, because Moscow has “backed down” after getting what it wanted most, many in both Russia and the West will dismiss as alarmist those who portray this as a dangerous extension of Russian government censorship.

Indeed, there are already those who are arguing that “the mass protest” of Internet users against what the Russian government sought to do was successful in getting the Kremlin to back down, thus setting the stage for all this to be proclaimed a triumph of democracy in Russia (kasparov.ru/material.php?id=55DBFC3C7E5CF).

And on the other, the way in which this case has played out will simultaneously make some reluctant to stand up to new Kremlin moves in this area, having deluded themselves into thinking that they are for domestic consumption and will always be reversed, and thus opening the way for even worse in the coming weeks and months.

Besides the obvious desire to censor the Internet which lies behind what Moscow has done, there are three especially disturbing aspects of this case: First, the court decision Moscow used was taken far from the center and from the kind of scrutiny that such cases normally get if they are within the ring road (kasparov.ru/material.php?id=55DC052AEBE4D).

Second, the case itself appears to have arisen because of demands for censorship by the Russian Orthodox Church, yet another indication of the Patriarchate’s growing influence on and interconnection with the Russian state and a development which by itself points to further efforts to promote its obscurantist agenda (kasparov.ru/material.php?id=55DC052AEBE4D).

And third, while Wikipedia did not simply cave into Moscow’s demands, it did take steps on its own to change the articles, thus opening the way for more such demands and more such changes in the future, especially if its editors or the editors of other such sites believe Moscow is really prepared to block access (versia.ru/vikipediya-sdelala-vse-chto-mogla-no-roskomnadzor-ne-privyk-k-soprotivleniyu).

The most likely reason Moscow backed down is not so much protests in Russia or abroad but rather the recognition of at least some in the Russian capital that blocking such portals is a fool’s errand. There are many ways to get around them, and Russians who use the Internet are familiar with them (echo.msk.ru/blog/nossik/1609780-echo/).

What everyone should remember is that the Wikipedia case was a kind of trial balloon, one that the Kremlin assumes will be a one-day wonder, and that in fact sets the stage both for a variety of new moves against the Internet outlined in Russia’s “digital sovereignty” law set to go into force on September 1 (profile.ru/rossiya/item/99212-osobennosti-tsifrovogo-suvereniteta).

Some of Moscow’s moves against freedom in this area are already taking off. Kseniya Kirillova of Novy Region-2 reports, for example, that Russian officials are now opening criminal cases against those who repost or even “like” anti-Kremlin articles on social media (nr2.com.ua/News/crime_and_accidents/V-Rossii-nachalas-ohota-na-layki--104552.html).

In a commentary on “Yezhednevny zhurnal” today, Igor Yakovenko puts what is happening in context. He begins by noting that tsarist censor Aleksandr Krasovsky in 1836 banned a book on the harmfulness of mushrooms because mushrooms are a favorite food of Orthodox Russians (ej.ru/?a=note&id=28458).

Now, in 2015, prosecutors in the village of Cherny Yar in Astrakhan oblast have done much the same thing with Wikipedia, and the “state-thinking” officials among the village’s 8,000 residents have gotten Moscow to go along with them and to play out the ban and then the lifting of the ban on Wikipedia, all in the name of protecting the Orthodox.

It is “unclear only why” such people would limit themselves to Wikipedia. Perhaps, the Moscow commentator says, they will move on to “ban the entire Internet as a whole, the Internet with its multitude of resources in which students and pupils can find materials for writing their works.”

“Following this logic,” Yakovenko says, “it is necessary to return even not to pre-internet times but directly to pre-literate ones when the transmission of knowledge took place by means of oral communication which undoubtedly improved their quality and the integrity of those studying.”

And he concludes: “for these people, it is not important that Russia’s prestige declines; it is important not to fall short in the eyes of the only source of power” they recognize. “The war with Ukraine has ever more thrown the Russian authorities back to a time when war was an end in itself.”

No comments:

Post a Comment