Trek on El Camino de Santiago becomes a metaphor for life:

by Elizabeth Simpson

When I was a kid, we played a game called chalk the walk.

We’d split into two groups, with one getting a head start to pick a hiding place, draw arrows on the sidewalk and then hide while the other group followed our arrows in search of us.

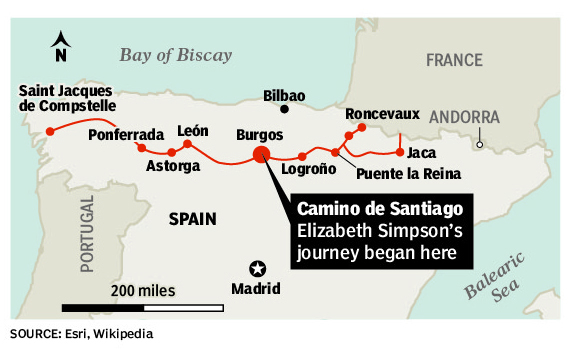

That game came to mind this summer when I spent two weeks on the Camino de Santiago, a 500-mile trail across northern Spain that’s marked with yellow arrows painted on curbs, signs, and sometimes, splashed right on the road.

That game came to mind this summer when I spent two weeks on the Camino de Santiago, a 500-mile trail across northern Spain that’s marked with yellow arrows painted on curbs, signs, and sometimes, splashed right on the road.

Every year, some 200,000 people trudge or bike along this centuries-old trail that goes from the French-Spanish border to Santiago de Compostela, where legend has it the remains of St. James lie.

The routine goes like this:

Wake. Walk. Eat. Sleep.

Repeat.

That might sound boring, but on a pilgrimage through picturesque towns, it’s exhilarating for these reasons:

You shed the ballast of daily life by taking only what you can carry.

You live in the moment of the next step, leaving how far you walk, where you will stay, up to the road.

You share stories with people from all over the world who walk on this faith:

The Camino provides.

I first heard about the Camino, or The Way of St. James, at my daughter’s graduation from Virginia Tech in 2012. Commencement speaker Annie Hesp, a Tech foreign language instructor, had led student groups there and also convinced actors Martin Sheen and Emilo Estevez to host a showing of their movie “The Way” on campus the previous year.

The father-son team made the 2010 movie, which is about a father who hikes the trail in honor of his son who died on the first day of his journey, as a labor of love. An upswing in popularity of the trail followed.

Alan: This summer, my 17 year old son Danny and I trekked the 75 mile stretch of El Camino de Santiago, La Ruta Portuguesa, from the splendid city of Tui (Tuy) on the Spanish side of the Portuguese border due north to Compostela where, according to tradition, el apostol Santiago's bones are buried. It was an inimitable experience for us both - a total "keeper" whose memory will bring satisfaction to my deathbed.

I’d forgotten about the idea until my parish priest, Father Brian Rafferty, took the pilgrimage. His doing so led me to buy “A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago,” by John Brierley.

I’d forgotten about the idea until my parish priest, Father Brian Rafferty, took the pilgrimage. His doing so led me to buy “A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago,” by John Brierley.

Before long I discovered my cousin had been hiking the most popular route from the French border to Santiago in pieces for the last several years.

He planned a segment in June that started in Burgos, across the high central plateau called the Meseta.

The next thing I knew, I was buying my first pair of hiking boots.

Between then and mid-June, I fielded questions from friends that went like this:

“So you must do a lot of hiking.”

“Nope, this will be my first experience.”

“Do you know Spanish?”

“Uh, no.”

“You and your cousin must be very close.”

“You and your cousin must be very close.”

“Umm, not really.”

Iglesia de Santa Maria in Castrojeriz on the Camino de Santiago in northern Spain. (Elizabeth Simpson | The Virginian-Pilot)

But I had reached the age my mother was when she died of cancer, a reminder not to put off notions. My industry was downsizing, shedding colleagues unceremoniously into jobs where the vacation clock started over again.

I wanted to put down my cell phone, get out of the car, and live in the moment.

So off I went.

From the moment I set foot on the trail in Burgos, I knew I had made the right decision.

I loved the cadence of walking. The absence of Wi-Fi. The majestic vistas of pastures brimming with poppies, checkerboard fields of wheat and sunflowers, red-roofed villages nestled into valleys.

No GPS, no pinging cell phone, just the inner compass of my body telling me when to slow down and get something to eat and rest.

We fell into a routine of walking, taking a long breakfast, walking again, stopping for the day in the afternoon. Showering, washing clothes in the bathroom sink, hanging them out to dry.

We ate Spanish style, with our largest meal midafternoon, then tapas and wine on a patio with pilgrims who happened along.

They spanned the globe. Most were doing the whole trek, which takes about a month.

You can imagine who fits into that category: students, teachers, retired people. Those who had lost their jobs. Those who had quit their jobs. People in transition.

There was a Frenchman, Alain Bouffier, who had retired just months before, and left from his doorstep.

A Spaniard who had hiked the trail several times already, but had recently had surgery to remove part of his stomach and wanted to see if he could do one more.

An 83-year-old artist from Oregon who was walking the trail in bits, staying in the smaller towns, stopping to set up her easel and paint.

An Australian who read about the Camino in a book, sold her business, trained, came last year, and fell on the first day coming down the Pyrenees.

She hopped, using walking sticks, to the next town and took a bus to Pamplona, where an X-ray showed a broken leg that sent her back home, where she had surgery to insert a plate in her leg.

Now, a year later, Jennifer Mackay, the never-say-die 60-year-old Aussie, was back to finish what she started.

Her advice: Take one step at a time. And don’t fall. (Get up if you do!)

Jennifer Mackay, a hiker from Australia, fell and broke her leg last year on the first day of her trek. She came back this year to finish the trail. (Elizabeth Simpson | The Virginian-Pilot)

People hike the Camino for many reasons. The beauty of the hike. The cultural and historical features of a trail with stretches of 2,000-year-old Roman-built roads. Some walk off pain or disappointment or boredom.

They also walk for the same spiritual reasons people have hiked it since the Middle Ages.

Churches, both adobe-walled humble ones and majestic cathedrals, adorn the trail. There’s a monastery where nuns wash your aching feet. Priests give special blessings at pilgrim Masses.

You never know where the pray-with-your-feet journey will lead.

One afternoon we arrived at ruins near Castrojeriz that were once a king’s palace and then a monastery of San Antón, the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony, dedicated to caring for the sick who came along the Camino.

Now it’s become an “albergue,” a hostel, run by volunteers in spartan conditions.

No electricity, no hot water, no Internet.

We picked out beds in the bunkhouse and shared a communal, candlelit dinner with a North Carolina hiker between high school and college, a Phoenix teacher and the two albergue volunteers, one from Ireland, the other from California.

The talk eventually led to the buzz about a 41-year-old woman who had quit her job in Arizona and disappeared off the trail in April near Astorga.

What happened to her? Would we ever know? One of the volunteers lamented that the news could dissuade women from hiking alone on a trail that’s always been known as a safe one. Still, it’s a story no one takes lightly. Roadside memorials attest to those who have died along the way.

But for the most part it’s an accommodating trail for the young and the old – a woman hiking with her baby, for instance, and hikers well into their 80s.

Father Gerard Postlethwaite, an English priest who had hiked the trail himself and has also taken a group of his parishioners, also dropped by San Antón to give us a special blessing using a sprig of rosemary and holy water.

He sees the trail as a metaphor for life, and a glimpse of the kingdom of God, where everyone helps each other home, crossing boundaries of language and culture and religion.

You see it at every turn: A couple tending each other’s blisters. A group of women who wander off track, but get stopped by Spanish farmers pointing out the right way.

I got turned around one night in Sahagún, coming back from an evening prayer at a church. Dark was settling in, my phone’s cellular off, so I stopped an elderly couple: “Por favor, donde esta la plaza mayor?”

My halting Spanish flagged me as a “peregrino,” or pilgrim.

The couple could have gestured me to where I needed to go. Instead they walked me to the street where it was a straight shot ahead to the plaza, where children were still playing with their parents and grandparents in the evening light.

When I was planning my trip in the spring, I had thought of taking a bus at some point to skip ahead to the end – I wanted to see Santiago de Compostela, after all – but decided to let the moment move me.

That was a point of the trip after all, to avoid over-planning. I found myself appreciating every step along the way, enjoying the company of my cousin – getting past the small talk of family reunions to the nub of our lives. I decided not to skip to the end. A bonus was hooking up in León with my cousin’s son, and granddaughter, Franca, who turned 10 on the trail.

It’s the age I felt on the whole of my journey, that age when everything feels fresh and anything is possible and it’s OK to play outside all day.

The lessons of the Camino can be learned anywhere along the trail; first that it’s about the journey rather than the destination.

The Camino way is not to judge, knowing everyone walks his or her own path. Some keep a blistering pace; others take their time.

I soon appreciated the simplicity of doing a 100-mile middle stretch, wondering whether I’ll ever finish. I hope to return, but I’ll wait to see where the yellow arrows of life lead me.

In the meantime, I think of Father Gerard’s words, that the Camino makes sense only if you live differently when you get home:

Live simply. Tend to others. Appreciate every step, misstep and detour.

And watch for the arrows.

Elizabeth Simpson, 757-222-5003, elizabeth.simpson@pilotonline.com

Pilgrim statue in Leon, with yellow arrow directing hikers on the way.

For more information on the Camino, check out these websites:

American Pilgrims on the Camino: bit.ly/1IclnAv

This organization provides information and issues pilgrim credentials, documents that authenticate your journey, which some of the “albergues” require.

Here’s a description from the website about lodging:

An albergue operates essentially like a youth hostel except that they exist for pilgrims. They provide basic overnight facilities. Most have dormitory-type sleeping arrangements, usually two-tiered bunks, and communal bathing and toilet facilities. Some have a set price, typically 6 to 10 euros a night; others operate on donations. Some serve meals; some have cooking facilities available; some have neither.

Online forum of Camino hikers: bit.ly/1EfZzc9

No comments:

Post a Comment