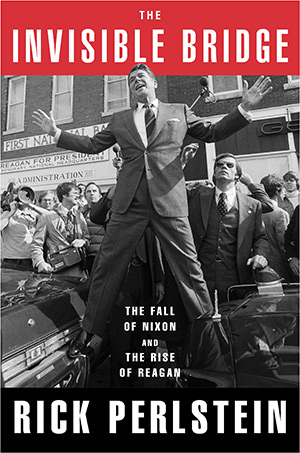

Photo by George Rose/Getty Images

"Future Generations Will Despise Ronald Reagan. Here's Why"

***

Excerpt: "This (kind of uproar) just isn’t what happens when Rick Perlstein releases a book. The first in his series, 2001’s Before the Storm, was praised by William F. Buckley. George Will called it “the best book yet on the social ferments that produced Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential candidacy”—in a largely positive review of Perlstein’s second book, Nixonland, which became a best-seller. What changed? This time Perlstein is writing about Ronald Reagan."

The Simplifier

By David Weigel

The third volume of Rick Perlstein’s history of modern conservatives chronicles the rise of Reagan.

If anyone is able to buy a copy of Rick Perlstein’s The Invisible Bridge, we’ll know that Craig Shirley lost. Last week, in advance of the Tuesday release of the third volume of Perlstein’s conservative movement history, right-winger Shirley claimed that Perlstein had plagiarized his book about Ronald Reagan’s 1976 primary challenge to President Gerald Ford. Shirley was asking for every copy of The Invisible Bridge to be destroyed, and for $25 million to be kindly deposited in his bank account.

Perlstein’s publisher did not budge. Shirley was credited in the book, after all, for saving the new author “3.76 months in research,” and the endnotes (published online, not in the book)slathered him with attributions. Simon and Schuster quickly rebutted the charges. The “plagiarism” story rocketed around the righty Internet anyway. The Daily Caller phoned up Shirley, who called the new book “a liberal’s version of conservative history.” TheWeekly Standard’s Fred Barnes, who had written the foreword to Shirley’s book, dutifully warned readers of the new controversy.

It was already plenty surreal, and then Roger Stone showed up. On Twitter, the Republican dirty trickster (whose avatar shows off his Richard Nixon back tattoo) asked whether the “lefty propagandist” was guilty of plagiarism. On Facebook, Stone continued his Purple Rose of Cairo act, walking from his history pages onto Perlstein’s wall, challenging and tweaking him. “Everyone in this controversy is a partisan,” wrote Stone, “but then, controversy sells books.”

This just isn’t what happens when Rick Perlstein releases a book. The first in his series, 2001’s Before the Storm, was praised by William F. Buckley. George Will called it “the best book yet on the social ferments that produced Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential candidacy”—in a largely positive review of Perlstein’s second book, Nixonland, which became a best-seller. What changed? This time Perlstein is writing about Ronald Reagan.

Goldwater, Nixon, Reagan—Perlstein has moved from covering a minor saint, to a martyr, to God. Thirteen years ago, when Perlstein profiled Goldwater’s movement, there had been only one recent biography of the Arizonan. There will be at least half a dozen new Reagan books this year alone, everything from a deep dive into the 1986 Reykjavik summit to a collection of leadership tips. Perlstein is challenging an image of the 40th president that is built on many such books, celebrated at Republican county dinners, and quoted by everyone from Ted Cruz (in his arguments for conservative revival) to Joe Scarborough (in his argument that no one should listen to Cruz).

Yes, technically, The Invisible Bridge is a history of January 1973 to August 1976, and Reagan’s own presidential campaign does not start until Page 546 (of 810). But in Perlstein’s telling, Reagan was the essential figure who understood that Americans wanted to revise their history in real time. The Invisible Bridge starts with Operation Homecoming, the negotiated release of Vietnam POWs that was preceded by years of patriotic kitsch. Perlstein recreates the mood by quoting copiously from letters to the editor, from columnists, POW speeches and TV broadcasts. He recalls that it was future right-wing Rep. Bob Dornan who came up with yellow armbands as trinkets of POW solidarity, and recovers forgotten tidbits about them, like how “a Wimbledon champ said that one cured his tennis elbow.”

The Invisible Bridge is bursting with these kinds of details. Perlstein seems to have inhaled every piece of news and pop culture from the period he’s covering. He finds reporters having to explain to their readers what “pro-life” means, the director of the CIA calling a reporter a “killer” (live on camera), and an Illinois legislator warring with the Equal Rights Amendment because “in Colorado, where they have ERA, men want to marry horses.”

The details matter—Ronald Reagan only made sense when the rest of America didn’t. Perlstein’s Reagan was introduced in Before the Storm as a talent who could explain conservatism for all the reasons Goldwater couldn’t. “Goldwater hardly ever mentioned a statistic,” Perlstein wrote. “He presumed you already knew what he meant. Reagan showed you … the stories went by faster than thought, like a seduction.”

In The Invisible Bridge, Perlstein explains that Reagan “had a way of telling a story that made it uncheckable.” He’d attribute facts and stories to “magazines” and “polls” without specifying which ones had come across his desk. (If you wonder how the existence of Google might have complicated this, remember what happened when Rand Paul started taking stories from Wikipedia.) Reagan defended Richard Nixon during Watergate so resolutely that the media started to write him off. When Gerald Ford was pursuing détente, Reagan warned that a weak America would “tempt the Soviet Union as it once tempted Hitler and the military rulers of Japan.” Perlstein’s every-news-clip-ever approach rewards a long read; he’ll quote Reagan’s welfare dissembling (a welfare-to-work program helped only 0.2 percent of recipients) and a few chapters later a woman on the street in New Hampshire will praise what Reagan did for those welfare moochers.

Perlstein also enjoys quoting the tastemakers who got it wrong. Before the Storm ended with Arthur Schlesinger predicting that Republicans would “lose every election” if they became too conservative. The Invisible Bridge ends with Elizabeth Drew concluding that Reagan is “too old” to run for president in 1980. (Perlstein graciously apologizes to Drew in the end notes.)

Conservative authors and Republican politicians love those lines, and love (retrospectively) how underrated Reagan was. Perlstein’s Reagan is incredibly talented, but he wins because the conditions are right for him to win. The country’s inward-looking, self-deprecating mood after Watergate was just that—a mood. It passed. It would be replaced by “a liturgy of absolution” and “cult of optimism.” “Others told you Vietnam was a crime, a waste—or, at best, something very, very complex,” writes Perlstein. “It took Ronald Reagan to explain how simple the whole thing was.”

Photo courtesy J. Cohn

So we remember 1974 and Watergate for the duplicity of a Republican administration. But the total collapse in confidence that government worked and could be trusted was, long term, a victory for conservatism. In the shorter term, the appetite for congressional investigations and exposés was sated in about a year, sped along when Democrats kept finding information that makes the Kennedys look worse than Nixon. One year after Nixon’s resignation, the Washington Post’s Katherine Graham was telling fellow publishers “to see a conspiracy and cover-up in everything is as myopic as to believe that no conspiracies or cover-ups exist.”

Conspiracies do exist. The best of Perlstein’s many, many lost-culture digressions are a study of a school curriculum backlash in West Virginia and a long look at the1975 bailout of New York City. (You know: “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”) Both are examples of how the New Right, with its origins in the Goldwater movement, “could lose a battle, suck it up, and then regroup to fight a thousand battles more.” In the school battles, the young Heritage Foundation found a populist cause that needed intellectual might, and the young direct mail movement found one that still raises gobs of money.

The conspiracy against New York was far more vast. Perlstein describes this as an early application of what Naomi Klein would dub “the shock doctrine.” Bankers saw New York’s crisis as an opportunity to force cutbacks that normal, labor politics would have prevented. Ford’s Treasury Secretary, William Simon, argued “nothing has destroyed New York’s finances but the liberal political formula.” This became conventional wisdom in no time, so much that a young Ken Auletta was soon blaming New York’s failure on a “noble experiment in local socialism and income distribution.”

Again, conservatives aren’t going to disagree with that. They’ll disagree with Perlstein’s view of the crisis, and vehemently disagree with a picture of Reagan that restores how he was viewed before presidency, deification, and landmark construction.

They shouldn’t sweat it. Reagan’s legacy has left too many Republicans hoping that a clone or simulacrum will come along and solve their political problems. Perlstein, while giving Reagan his due, rejects Great Man theory. Conservatives can win when the conditions are right, and when people embrace patriotism while rejecting the state. Imagine what Reagan could have done with Obamacare or the IRS story. Then consider how well Republicans have done, how much they've been able to exploit the Obama administration’s failures, without him.

---

The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan by Rick Perlstein. Simon and Schuster.

No comments:

Post a Comment