Darwin's Battle with Anxiety

Charles Darwin was undoubtedly among the most significant thinkers humanity has ever produced. But he was also a man of peculiar mental habits, from his stringent daily routine to his despairingly despondent moods to his obsessive list of the pros and cons of marriage. Those, it turns out, may have been simply Darwin's best adaptation strategy for controlling a malady that dominated his life, the same one that afflicted Vincent van Gogh – a chronic anxiety, which rendered him among the legions of great minds evidencing the relationship between creativity and mental illness.

Charles Darwin was undoubtedly among the most significant thinkers humanity has ever produced. But he was also a man of peculiar mental habits, from his stringent daily routine to his despairingly despondent moods to his obsessive list of the pros and cons of marriage. Those, it turns out, may have been simply Darwin's best adaptation strategy for controlling a malady that dominated his life, the same one that afflicted Vincent van Gogh – a chronic anxiety, which rendered him among the legions of great minds evidencing the relationship between creativity and mental illness.

In My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind (public library) – his sweeping mental health memoir, exploring our culture of anxiety and its costs – The Atlanticeditor Scott Stossel examines Darwin's prolific diaries and letters, proposing that the reason the great scientist spent a good third of his waking hours on the Beagle in bed or sick, as well as the cause of his lifelong laundry list of medical symptoms, was his struggle with anxiety.

Stossel writes:

Observers going back to Aristotle have noted that nervous dyspepsia and intellectual accomplishment often go hand in hand. Sigmund Freud's trip to the United States in 1909, which introduced psychoanalysis to this country, was marred (as he would later frequently complain) by his nervous stomach and bouts of diarrhea. Many of the letters between William and Henry James, first-class neurotics both, consist mainly of the exchange of various remedies for their stomach trouble.

But for debilitating nervous stomach complaints, nothing compares to that which afflicted poor Charles Darwin, who spent decades of his life prostrated by his upset stomach.

That affliction of afflictions, Stossel argues, was Darwin's overpowering anxiety – something that might explain why his influential studies of human emotion were of such intense interest to him. Stossel points to a "Diary of Health" that the scientist kept for six years between the ages of 40 and 46 at the urging of his physician. He filled dozens of pages with complaints like "chronic fatigue, severe stomach pain and flatulence, frequent vomiting, dizziness ('swimming head,' as Darwin described it), trembling, insomnia, rashes, eczema, boils, heart palpitations and pain, and melancholy."

In 1865 – six years after the completion of The Origin of Species – a distraught 56-year-old Darwin wrote a letter to another physician, John Chapman, outlining the multitude of symptoms that had bedeviled him for decades:

For 25 years extreme spasmodic daily & nightly flatulence: occasional vomiting, on two occasions prolonged during months. Vomiting preceded by shivering, hysterical crying[,] dying sensations or half-faint. & copious very palid urine. Now vomiting & every passage of flatulence preceded by ringing of ears, treading on air & vision .... Nervousness when E leaves me.

"E" refers to his wife Emma, who loved Darwin dearly and who mothered his ten children – a context in which his "nervousness" does suggest anxiety's characteristic tendency to wring worries out of unlikely scenarios, not to mention being direct evidence of the very term "separation anxiety."

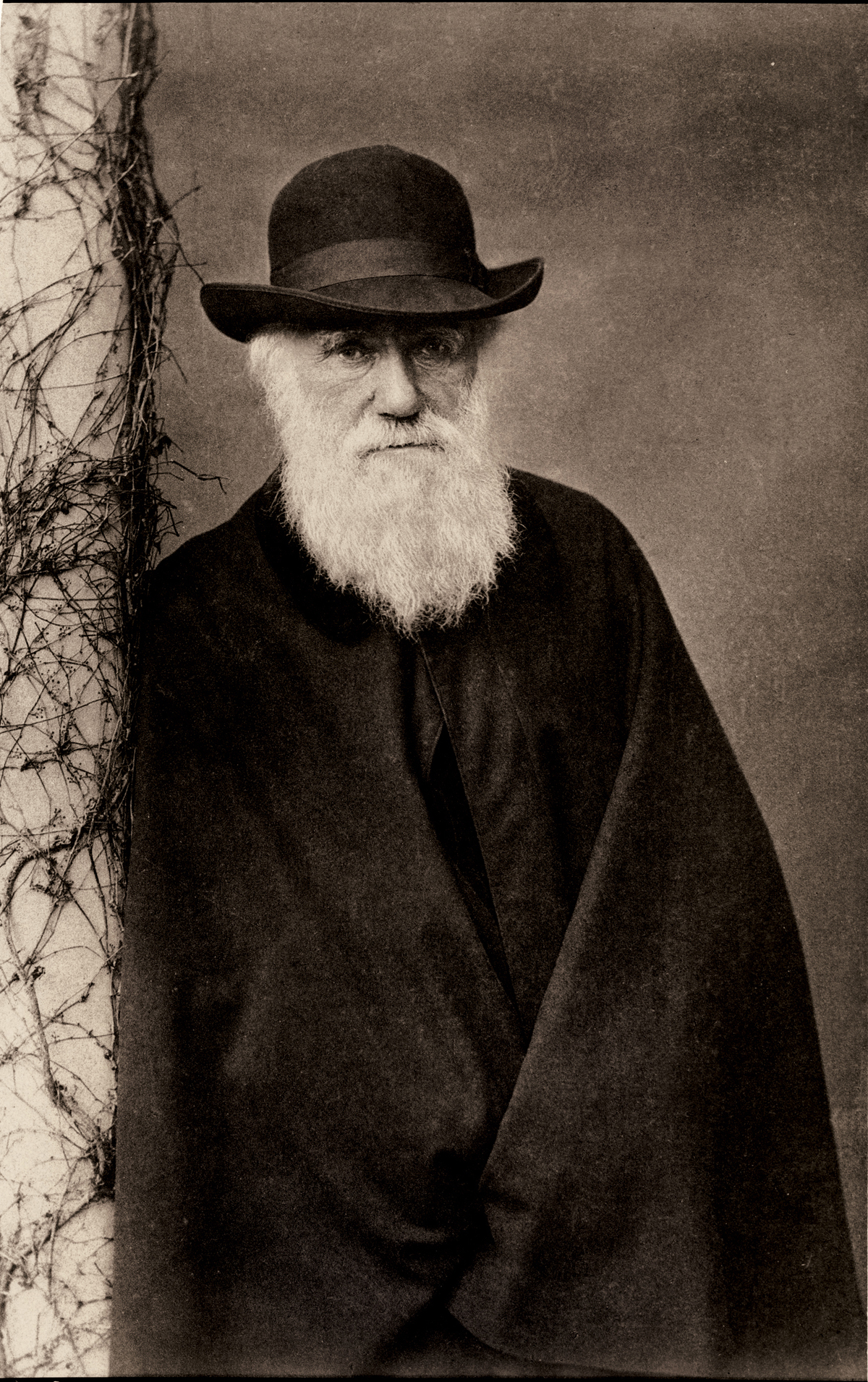

Illustration from The Smithsonian's Darwin: A Graphic Biography

Stossel chronicles Darwin's descent:

Darwin was frustrated that dozens of physicians, beginning with his own father, had failed to cure him. By the time he wrote to Dr. Chapman, Darwin had spent most of the past three decades – during which time he'd struggled heroically to write On the Origin of Species housebound by general invalidism. Based on his diaries and letters, it's fair to say he spent a full third of his daytime hours since the age of twenty-eight either vomiting or lying in bed.

Chapman had treated many prominent Victorian intellectuals who were "knocked up" with anxiety at one time or another; he specialized in, as he put it, those high-strung neurotics "whose minds are highly cultivated and developed, and often complicated, modified, and dominated by subtle psychical conflicts, whose intensity and bearing on the physical malady it is difficult to comprehend." He prescribed the application of ice to the spinal cord for almost all diseases of nervous origin.Chapman came out to Darwin's country estate in late May 1865, and Darwin spent several hours each day over the next several months encased in ice; he composed crucial sections of The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication with ice bags packed around his spine.The treatment didn't work. The "incessant vomiting" continued. So while Darwin and his family enjoyed Chapman's company ("We liked Dr. Chapman so very much we were quite sorry the ice failed for his sake as well as ours" Darwin's wife wrote), by July they had abandoned the treatment and sent the doctor back to London.Chapman was not the first doctor to fail to cure Darwin, and he would not be the last. To read Darwin's diaries and correspondence is to marvel at the more or less constant debilitation he endured after he returned from the famous voyage of the Beagle in 1836. The medical debate about what, exactly, was wrong with Darwin has raged for 150 years. The list proposed during his life and after his death is long: amoebic infection, appendicitis, duodenal ulcer, peptic ulcer, migraines, chronic cholecystitis, "smouldering hepatitis," malaria, catarrhal dyspepsia, arsenic poisoning, porphyria, narcolepsy, "diabetogenic hyper-insulism," gout, "suppressed gout," chronic brucellosis (endemic to Argentina, which the Beagle had visited), Chagas' disease (possibly contracted from a bug bite in Argentina), allergic reactions to the pigeons he worked with, complications from the protracted seasickness he experienced on the Beagle, and 'refractive anomaly of the eyes.' I've just read an article, "Darwin's Illness Revealed," published in a British academic journal in 2005, that attributes Darwin's ailments to lactose intolerance.

Various competing hypotheses attempted to diagnose Darwin, both during his lifetime and after. But Stossel argues that "a careful reading of Darwin's life suggests that the precipitating factor in every one of his most acute attacks of illness was anxiety." His greatest rebuttal to other medical theories is a seemingly simple, positively profound piece of evidence:

When Darwin would stop working and go walking or riding in the Scottish Highlands or North Wales, his health would be restored.

(Of course, one need not suffer from debilitating anxiety in order to reap the physical and mental benefits of walking, arguably one of the simplest yet most rewarding forms of psychic restoration and a powerful catalyst for creativity.)

My Age of Anxiety is a fascinating read in its totality. Complement it with a timeless antidote to anxiety from Alan Watts, then revisit Darwin's brighter side with his beautiful reflections on family, work, and happiness.

No comments:

Post a Comment