Alan: Ursula Le Guin was a favorite author of my University of Toronto mentor and teacher, Rev. J. Edgar Bruns, author of "The Christian Buddhism Of St. John: New Insights Into The Fourth Gospel."

My favorite work of fiction is LeGuin's "A Wizard of Earthsea."

A fabulous story expressed in exquisite language.

Ursula has also translated Lao Tzu's (Laosi's) "Tao Te Ching."

My favorite translation of "Tao Te Ching" (by Lionel Giles, 1905) is freely available online at http://sacred-texts.com/tao/salt/index.htm

"100 Children's Book To Read In A Lifetime"

***

Ursula K. Le Guin on Aging and What Beauty Really Means

by Maria Popova

“There are a whole lot of ways to be perfect, and not one of them is attained through punishment.”

“A Dog is, on the whole, what you would call a simple soul,” T.S. Eliot simpered in his beloved 1930s poem “The Ad-dressing of Cats,”proclaiming that “Cats are much like you and me.” Indeed, cats have a long history of being anthropomorphized in dissecting the human condition — but, then again, so do dogs. We’ve always used our feline and canine companions to better understand ourselves, but nowhere have Cat and Dog served a more poignant metaphorical purpose than in the 1992 essay“Dogs, Cats, and Dancers: Thoughts about Beauty” by Ursula K. Le Guin (b. October 21, 1929), found in the altogether spectacular volume The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (public library), which also gave us Le Guin, at her finest and sharpest, on being a man.

“A Dog is, on the whole, what you would call a simple soul,” T.S. Eliot simpered in his beloved 1930s poem “The Ad-dressing of Cats,”proclaiming that “Cats are much like you and me.” Indeed, cats have a long history of being anthropomorphized in dissecting the human condition — but, then again, so do dogs. We’ve always used our feline and canine companions to better understand ourselves, but nowhere have Cat and Dog served a more poignant metaphorical purpose than in the 1992 essay“Dogs, Cats, and Dancers: Thoughts about Beauty” by Ursula K. Le Guin (b. October 21, 1929), found in the altogether spectacular volume The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (public library), which also gave us Le Guin, at her finest and sharpest, on being a man.

Le Guin contrasts the archetypal temperaments of our favorite pets:

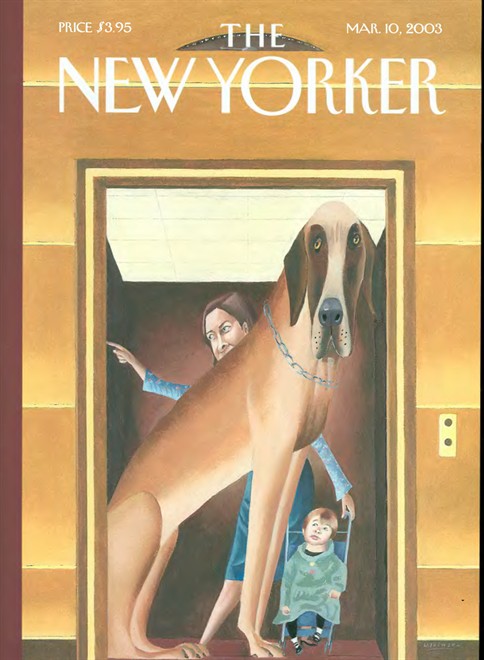

Dogs don’t know what they look like. Dogs don’t even know what size they are. No doubt it’s our fault, for breeding them into such weird shapes and sizes. My brother’s dachshund, standing tall at eight inches, would attack a Great Dane in the full conviction that she could tear it apart. When a little dog is assaulting its ankles the big dog often stands there looking confused — “Should I eat it? Will it eat me? I ambigger than it, aren’t I?” But then the Great Dane will come and try to sit in your lap and mash you flat, under the impression that it is a Peke-a-poo.

Cats, on the other hand, have a wholly different scope of self-awareness:

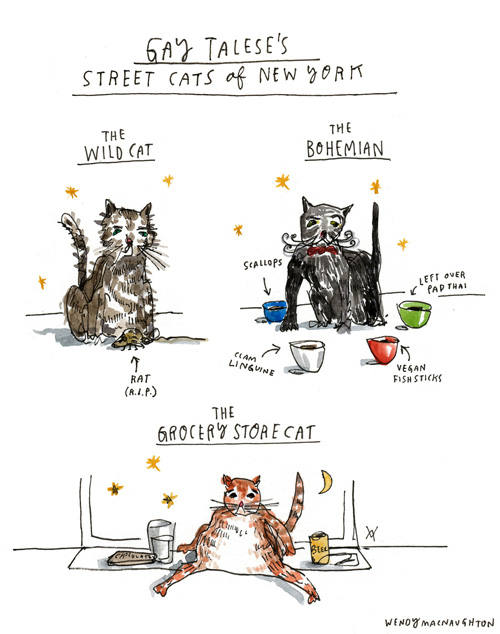

Cats know exactly where they begin and end. When they walk slowly out the door that you are holding open for them, and pause, leaving their tail just an inch or two inside the door, they know it. They know you have to keep holding the door open. That is why their tail is there. It is a cat’s way of maintaining a relationship.Housecats know that they are small, and that it matters. When a cat meets a threatening dog and can’t make either a horizontal or a vertical escape, it’ll suddenly triple its size, inflating itself into a sort of weird fur blowfish, and it may work, because the dog gets confused again — “I thought that was a cat. Aren’t I bigger than cats? Will it eat me?”

More than that, Le Guin notes, cats are aesthetes, vain and manipulative in their vanity. In a passage that takes on whole new layers of meaning twenty years later, in the heyday of the photographic cat meme, she writes:

Cats have a sense of appearance. Even when they’re sitting doing the wash in that silly position with one leg behind the other ear, they know what you’re sniggering at. They simply choose not to notice. I knew a pair of Persian cats once; the black one always reclined on a white cushion on the couch, and the white one on the black cushion next to it. It wasn’t just that they wanted to leave cat hair where it showed up best, though cats are always thoughtful about that. They knew where they looked best. The lady who provided their pillows called them her Decorator Cats.

A master of bridging the playful and the poignant, Le Guin returns to the human condition:

A lot of us humans are like dogs: we really don’t know what size we are, how we’re shaped, what we look like. The most extreme example of this ignorance must be the people who design the seats on airplanes. At the other extreme, the people who have the most accurate, vivid sense of their own appearance may be dancers. What dancers look like is, after all, what they do.

Echoing legendary choreographer Merce Cunningham’s contemplation of dance as “the human body moving in time-space,” Le Guin considers the dancers she knows and their extraordinary lack of “illusions or confusions about what space they occupy.” Recounting the anecdote of one young dancer who upon scraping his ankle exclaimed, “I have an owie on my almost perfect body!” Le Guin writes:

It was endearingly funny, but it was also simply true: his body is almost perfect. He knows it is, and knows where it isn’t. He keeps it as nearly perfect as he can, because his body is his instrument, his medium, how he makes a living, and what he makes art with. He inhabits his body as fully as a child does, but much more knowingly. And he’s happy about it.

Photograph from Helen Keller's life-changing visit to Martha Graham's dance studio. Click image for details.

What dance does, above all, is offer the promise of precisely such bodily happiness — not of perfection, but of satisfaction. Dancers, Le Guin argues, are “so much happier than dieters and exercisers.” She considers the impossible ideals of the latter, which cripple them in the same way that perfectionism cripples creativity in writing and art:

Perfection is “lean” and “taut” and “hard” — like a boy athlete of twenty, a girl gymnast of twelve. What kind of body is that for a man of fifty or a woman of any age? “Perfect”? What’s perfect? A black cat on a white cushion, a white cat on a black one . . . A soft brown woman in a flowery dress . . . There are a whole lot of ways to be perfect, and not one of them is attained through punishment.

And just like that, Le Guin pirouettes, elegantly but imperceptibly, from the lighthearted to the serious. Reflecting on various cultures’ impossible and often painful ideals of human beauty, “especially of female beauty,” she writes:

I think of when I was in high school in the 1940s: the white girls got their hair crinkled up by chemicals and heat so it would curl, and the black girls got their hair mashed flat by chemicals and heat so it wouldn’t curl. Home perms hadn’t been invented yet, and a lot of kids couldn’t afford these expensive treatments, so they were wretched because they couldn’t follow the rules, the rules of beauty.Beauty always has rules. It’s a game. I resent the beauty game when I see it controlled by people who grab fortunes from it and don’t care who they hurt. I hate it when I see it making people so self-dissatisfied that they starve and deform and poison themselves. Most of the time I just play the game myself in a very small way, buying a new lipstick, feeling happy about a pretty new silk shirt.

Le Guin, who writes about aging with more grace, humor, and dignity than any other writer I’ve read, turns to the particularly stifling ideal of eternal youth:

One rule of the game, in most times and places, is that it’s the young who are beautiful. The beauty ideal is always a youthful one. This is partly simple realism. The young arebeautiful. The whole lot of ’em. The older I get, the more clearly I see that and enjoy it.[...]And yet I look at men and women my age and older, and their scalps and knuckles and spots and bulges, though various and interesting, don’t affect what I think of them. Some of these people I consider to be very beautiful, and others I don’t. For old people, beauty doesn’t come free with the hormones, the way it does for the young. It has to do with bones. It has to do with who the person is. More and more clearly it has to do with what shines through those gnarly faces and bodies.

But what makes the transformations of aging so anguishing, Le Guin poignantly observes, isn’t the loss of beauty — it’s the loss of identity, a frustratingly elusive phenomenon to begin with. She writes:

I know what worries me most when I look in the mirror and see the old woman with no waist. It’s not that I’ve lost my beauty—I never had enough to carry on about. It’s that that woman doesn’t look like me. She isn’t who I thought I was.[...]We’re like dogs, maybe: we don’t really know where we begin and end. In space, yes; but in time, no.[...]A child’s body is very easy to live in. An adult body isn’t. The change is hard. And it’s such a tremendous change that it’s no wonder a lot of adolescents don’t know who they are. They look in the mirror — that is me? Who’s me?And then it happens again, when you’re sixty or seventy.

In a sentiment that calls Rilke to mind — “I am not one of those who neglect the body in order to make of it a sacrificial offering for the soul,” he memorably wrote,“since my soul would thoroughly dislike being served in such a fashion.” — Le Guin admonishes against our impulse to intellectualize out of the body, away from it:

Who I am is certainly part of how I look and vice versa. I want to know where I begin and end, what size I am, and what suits me… I am not “in” this body, I am this body. Waist or no waist.But all the same, there’s something about me that doesn’t change, hasn’t changed, through all the remarkable, exciting, alarming, and disappointing transformations my body has gone through. There is a person there who isn’t only what she looks like, and to find her and know her I have to look through, look in, look deep. Not only in space, but in time.[...]There’s the ideal beauty of youth and health, which never really changes, and is always true. There’s the ideal beauty of movie stars and advertising models, the beauty-game ideal, which changes its rules all the time and from place to place, and is never entirely true. And there’s an ideal beauty that is harder to define or understand, because it occurs not just in the body but where the body and the spirit meet and define each other.

And yet for all the ideals we impose on our earthy embodiments, Le Guin argues in her most poignant but, strangely, most liberating point, it is death that ultimately illuminates the full spectrum of our beauty — death, the ultimate equalizer of time and space; death, the great clarifier that makes us see that, asRebecca Goldstein put it, “a person whom one loves is a world, just as one knows oneself to be a world.” With this long-view lens, Le Guin remembers her own mother and the many dimensions of her beauty:

My mother died at eighty-three, of cancer, in pain, her spleen enlarged so that her body was misshapen. Is that the person I see when I think of her? Sometimes. I wish it were not. It is a true image, yet it blurs, it clouds, a truer image. It is one memory among fifty years of memories of my mother. It is the last in time. Beneath it, behind it is a deeper, complex, ever-changing image, made from imagination, hearsay, photographs, memories. I see a little red-haired child in the mountains of Colorado, a sad-faced, delicate college girl, a kind, smiling young mother, a brilliantly intellectual woman, a peerless flirt, a serious artist, a splendid cook—I see her rocking, weeding, writing, laughing — I see the turquoise bracelets on her delicate, freckled arm — I see, for a moment, all that at once, I glimpse what no mirror can reflect, the spirit flashing out across the years, beautiful.That must be what the great artists see and paint. That must be why the tired, aged faces in Rembrandt’s portraits give us such delight: they show us beauty not skin-deep but life-deep.

The Wave in the Mind remains the kind of book that stays with you for life — the kind of book that is life.

No comments:

Post a Comment