California Drought Becoming Political Football

***

No running water.

In many rural areas, it's been half a year since toilets flushed.

By Jennifer Medina

In many rural areas, it's been half a year since toilets flushed.

By Jennifer Medina

PORTERVILLE, Calif. — After a nine-hour day working at a citrus packing plant, her body covered in a sheen of fruit wax and dust, there is nothing Angelica Gallegos wants more than a hot shower, with steam to help clear her throat and lungs.

“I can just picture it, that feeling of finally being clean — really refreshed and clean,” Ms. Gallegos, 37, said one recent evening.

But she has not had running water for more than five months — nor is there any tap water in her near future — because of a punishing and relentless drought in California. In the Gallegos household and more than 500 others in Tulare County, residents cannot flush a toilet, fill a drinking glass, wash dishes or clothes, or even rinse their hands without reaching for a bottle or bucket.

Even more so than the Okies who came here fleeing the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, the people now living on this parched land are stuck. “We don’t have the money to move, and who would buy this house without water?” said Ms. Gallegos, who grew up in the area and shares a tidy mobile home with her husband and two daughters. “When you wake up in the middle of the night sick to your stomach, you have to think about where the water bottle is before you can use the toilet.”

Now in its third year, the state’s record-breaking drought is being felt in many ways: vanishing lakes and rivers, lost agricultural jobs, fallowed farmland, rising water bills, suburban yards gone brown. But nowhere is the situation as dire as in East Porterville, a small rural community in Tulare County where life’s daily routines have been completely upended by the drying of wells and, in turn, the disappearance of tap water.

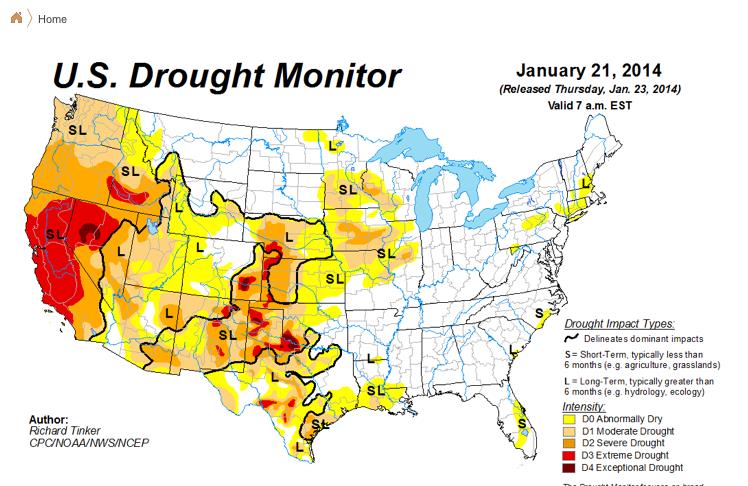

95% of California's land mass is suffering "severe, extreme or exceptiona" drought.

“Everything has changed,” said Yolanda Serrato, 54, who has spent most of her life here. Until this summer, the lawn in front of her immaculate three-bedroom home was a lush green, with plants dotting the perimeter. As her neighbors’ wells began running dry, Ms. Serrato warned her three children that they should cut down on hourlong showers, but they mostly rebuffed her. “They kept saying, ‘No, no, Mama, you’re just too negative,’ ” she said.

Then the sink started to sputter. These days, the family of five relies on a water tank in front of their home that they received through a local charity. The sole neighbor with a working well allows them to hook up to his water at night, saving them from having to use buckets to flush toilets in the middle of the night. On a recent morning, there was still a bit of the neighbor’s well water left, trickling out the kitchen faucet, taking over 10 minutes to fill two three-quart pots.

“You don’t think of water as privilege until you don’t have it anymore,” said Ms. Serrato, whose husband works in the nearby fields. “We were very proud of making a life here for ourselves, for raising children here. We never ever expected to live this way.”

Like Ms. Serrato, the vast majority of residents here in the Sierra Nevada foothills are Mexican immigrants, drawn to the state’s Central Valley to work in the expansive agricultural fields. Many here have spent lifetimes scraping together money to buy their own small slice of land, often with a mobile home sitting on top. Hundreds of these homes are hooked to wells that are treated as private property: When the water is there, it is solely controlled by owners. Because the land is unincorporated, it is not part of a municipal water system, and connecting to one would be prohibitively expensive.

The Gallegos family’s drinking water comes only from bottles, mostly received through donations but sometimes bought at the gas station. For showering, washing dishes and flushing toilets, the family relies on buckets filled with water from a tank set in the front lawn, which Mr. Gallegos replenishes every other day at the county fire station. Often, the water runs out before he returns home from his job as a mechanic, forcing Ms. Gallegos to wait for hours before she can clean.

The family has spent hundreds of dollars to wash their clothes at the laundromat and on paper goods to avoid washing dishes. Ms. Gallegos recently told her 10-year-old daughter that there was no money left to pay for her after-school cheerleading club.

The local high school has begun allowing students to arrive early and shower there. Parents often keep their children home from school if they have not bathed, worried that they could lose custody if the authorities deem the students too dirty, a rumor that county officials have tried to dismiss. Mothers who normally take pride in their home-cooked meals now rely on canned and fast food, because washing fresh vegetables uses too much water.

Ms. Serrato and others receive help from a local charity organization, the Porterville Area Coordinating Council, which opens its doors each weekday morning to hand out water. A whiteboard displays the distribution system: Families of four receive three cases of bottled water and two gallon jugs, families of six get four cases and four gallon jugs, and so on.

For months, families called county and state officials asking what they should do when their water ran out, only to be told that there was no public agency that could help them.

“Nobody knows where to go, who to talk to: These aren’t people who rely on government to help,” said Donna Johnson, 72, an East Porterville resident whose own well went dry in July. As she began learning that hundreds of her neighbors were also out of water, she used her own money to buy gallons of water, handed them out of her truck and compiled a list of those in need. County officials rely on her list as the most complete snapshot of who needs help; dozens are added each day. “It’s a slow-moving disaster that nobody knows how to handle,” Ms. Johnson said.

State officials say that at least 700 households have no access to running water, but they acknowledge that there could be hundreds more, with many rural well-owners not knowing whom to contact. Tulare County, just south of Fresno, recently began aggressively tracking homes without running water, delivering bottles to hundreds of homes and offering applications for biweekly water deliveries, using private donations and money from a state grant. In August, the county placed a 5,000-gallon tank of water in front of a fire station on Lake Success Road, and plans to add a second soon. A sign in English and Spanish declares, “Do not use for drinking,” but officials suspect that many do.

“We will give people water as long as we have it, but the truth is, we don’t really know how long that will be,” said Andrew Lockman, who leads the Tulare County Office of Emergency Services. “We can’t offer anyone a long-term solution right now. There is a massive gap between need and resources to deal with it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment