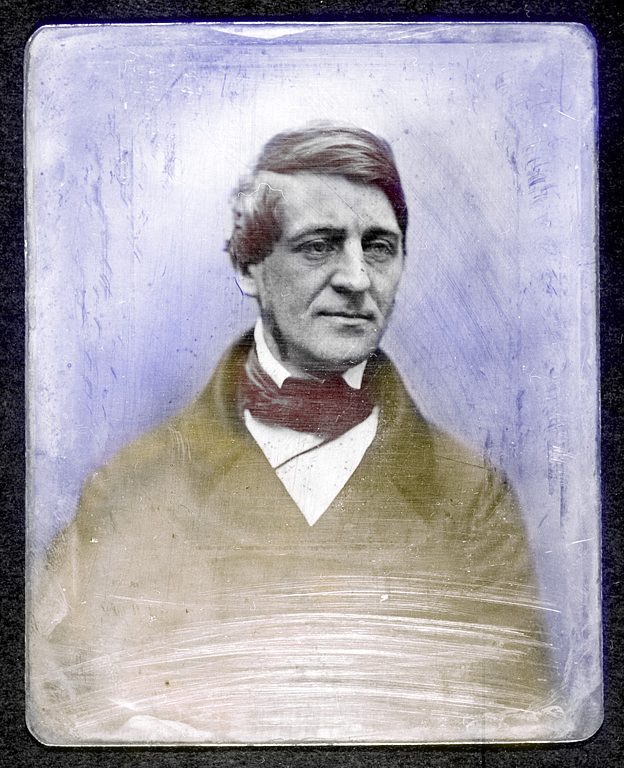

Truth and Tenderness: Ralph Waldo Emerson on Friendship and Its Two Essential Conditions

by Maria Popova

“What is so delicious as a just and firm encounter of two, in a thought, in a feeling?”

It’s been argued that friendship is a greater gift than romantic love (though it’s not uncommon for one to turn abruptly into the other), but whatever the case, friendship is certainly one of the most rewarding fruits of life — from the sweetness of childhood friendships to the trickiness of workplace ones. This delicate dance has been examined by thinkers from Aristotle toFrancis Bacon to Thoreau, but none more thoughtfully than by Ralph Waldo Emerson. In an essay on the subject, found in his altogether soul-expanding Essays and Lectures (public library; free download), Emerson considers the intricate dynamics of friendship, beginning with our often underutilized innate capacities:

It’s been argued that friendship is a greater gift than romantic love (though it’s not uncommon for one to turn abruptly into the other), but whatever the case, friendship is certainly one of the most rewarding fruits of life — from the sweetness of childhood friendships to the trickiness of workplace ones. This delicate dance has been examined by thinkers from Aristotle toFrancis Bacon to Thoreau, but none more thoughtfully than by Ralph Waldo Emerson. In an essay on the subject, found in his altogether soul-expanding Essays and Lectures (public library; free download), Emerson considers the intricate dynamics of friendship, beginning with our often underutilized innate capacities:We have a great deal more kindness than is ever spoken. Barring all the selfishness that chills like east winds the world, the whole human family is bathed with an element of love like a fine ether. How many persons we meet in houses, whom we scarcely speak to, whom yet we honor, and who honor us! How many we see in the street, or sit with in church, whom, though silently, we warmly rejoice to be with! Read the language of these wandering eyebeams. The heart knoweth…The emotions of benevolence … from the highest degree of passionate love, to the lowest degree of good will, they make the sweetness of life.

More than mere gratification of the heart, however, Emerson celebrates friendship as something that expands and enriches our intellectual landscape:

Our intellectual and active powers increase with our affection. The scholar sits down to write, and all his years of meditation do not furnish him with one good thought or happy expression; but it is necessary to write a letter to a friend, and, forthwith, troops of gentle thoughts invest themselves, on every hand, with chosen words.

But beyond the rewards of emotion and intellect lies an even deeper satisfaction — that of the soul:

What is so delicious as a just and firm encounter of two, in a thought, in a feeling? How beautiful, on their approach to this beating heart, the steps and forms of the gifted and the true! The moment we indulge our affections, the earth is metamorphosed; there is no winter, and no night; all tragedies, all ennuis vanish; all duties even; nothing fills the proceeding eternity but the forms all radiant of beloved persons. Let the soul be assured that somewhere in the universe it should rejoin its friend, and it would be content and cheerful alone for a thousand years.

For Emerson, friendship isn’t something that can be willed or forced but, rather, the natural byproduct of our interaction with the world. A century and a half before the modern social web, he pens a passage that rings with extraordinary poignancy and prescience today:

We weave social threads of our own, a new web of relations; and, as many thoughts in succession substantiate themselves, we shall by-and-by stand in a new world of our own creation, and no longer strangers and pilgrims in a traditionary globe. My friends have come to me unsought.

Drawing from 'The Lion and the Bird' by Marianne Dubuc, a tender illustrated story about loyalty and the gift of friendship. Click image for more.

In the deepest of friendships, Emerson finds an element of reverie as the two friends amplify each other’s goodness through a boundless generosity of spirit:

I must feel pride in my friend’s accomplishments as if they were mine, and a property in his virtues. I feel as warmly when he is praised, as the lover when he hears applause of his engaged maiden. We over-estimate the conscience of our friend. His goodness seems better than our goodness, his nature finer, his temptations less. Everything that is his, — his name, his form, his dress, books and instruments, — fancy enhances. Our own thought sounds new and larger from his mouth.

But even the most absolute of friendships, Emerson argues, have a certain pace of presence and absence, a natural rhythm of “comings and goings” that should be respected rather than bemoaned as a weakness in the relationship:

The soul environs itself with friends, that it may enter into a grander self-acquaintance or solitude; and it goes alone, for a season, that it may exalt its conversation or society. This method betrays itself along the whole history of our personal relations. The instinct of affection revives the hope of union with our mates, and the returning sense of insulation recalls us from the chase. Thus every man passes his life in the search after friendship, and if he should record his true sentiment, he might write a letter like this, to each new candidate for his love:Dear Friend:—

If I was sure of thee, sure of thy capacity, sure to match my mood with thine, I should never think again of trifles, in relation to thy comings and goings. I am not very wise; my moods are quite attainable; and I respect thy genius; it is to me as yet unfathomed; yet dare I not presume in thee a perfect intelligence of me, and so thou art to me a delicious torment. Thine ever, or never.

To rush these rhythms or force friendship to comply to a specific fantasy, Emerson gently admonishes, would be an assault on the relationship:

Our friendships hurry to short and poor conclusions, because we have made them a texture of wine and dreams, instead of the tough fiber of the human heart. The laws of friendship are great, austere, and eternal, of one web with the laws of nature and of morals. But we have aimed at a swift and petty benefit, to suck a sudden sweetness.

In a sentiment that John Steinbeck would come to echo a century later in the context of love, writing to his teenage son that “the main thing is not to hurry [for] nothing good gets away,” Emerson argues that to be impatient in friendship is to mistrust the depth of the relationship and to deny the resilience and immutability of the friend’s affections:

Our impatience is thus sharply rebuked. Bashfulness and apathy are a tough husk in which a delicate organization is protected from premature ripening. It would be lost if it knew itself before any of the best souls were yet ripe enough to know and own it. Respect the naturalangsamkeit [German for the slowness of natural development] which hardens the ruby in a million years, and works in duration, in which Alps and Andes come and go as rainbows. The good spirit of our life has no heaven which is the price of rashness. Love, which is the essence of God, is not for levity, but for the total worth of man. Let us not have this childish luxury in our regards, but the austerest worth; let us approach our friend with an audacious trust in the truth of his heart, in the breadth, impossible to be overturned, of his foundations.[...]I do not wish to treat friendships daintily, but with roughest courage. When they are real, they are not glass threads or frost-work, but the solidest thing we know.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from 'I’ll Be You and You Be Me' by Ruth Krauss, 1954. Click image for more.

And yet how rare it is to have a friend with whom one can be earnest to the point of absoluteness — who doesn’t require the veneer of self-consciousness and the shield of cynicism. Echoing Aristotle’s assertion that a friend holds a mirror up to us and thus brings us closer to ourselves, Emerson outlines the two key elements of a true, solid, soul-fortifying friendship:

There are two elements that go to the composition of friendship, each so sovereign, that I can detect no superiority in either, no reason why either should be first named. One is Truth. A friend is a person with whom I may be sincere. Before him, I may think aloud. I am arrived at last in the presence of a man so real and equal that I may drop even those undermost garments of dissimulation, courtesy, and second thought, which men never put off, and may deal with him with the simplicity and wholeness, with which one chemical atom meets another. Sincerity is the luxury allowed, but diadems and authority, only to the highest rank, thatbeing permitted to speak truth as having none above it to court or conform unto. Every man alone is sincere. At the entrance of a second person, hypocrisy begins… We cover up our thought from him under a hundred folds.[...]The other element of friendship is tenderness. We are holden to men by every sort of tie, by blood, by pride, by fear, by hope, by lucre, by lust, by hate, by admiration, by every circumstance and badge and trifle, but we can scarce believe that so much character can subsist in another as to draw us by love. Can another be so blessed, and we so pure, that we can offer him tenderness? When a man becomes dear to me, I have touched the goal of fortune.

In another stroke of exalting prescience, Emerson bemoans — more than a century before our networking-preoccupied, self-promotional society — the superficiality and transactional ego-stroking that defines most human interactions, the vacant “chat of markets or reading-rooms.” (We all know the people who bestow upon professional relations and marginal acquaintances the misplaced label “friend” in an act of name-dropping or self-inflation — an injustice against true friendship.) Emerson laments:

To most of us society shows not its face and eye, but its side and its back. To stand in true relations with men in a false age, is worth a fit of insanity, is it not? We can seldom go erect. Almost every man we meet requires some civility, — requires to be humored; he has some fame, some talent, some whim of religion or philanthropy in his head that is not to be questioned, and which spoils all conversation with him. But a friend is a sane man who exercises not my ingenuity, but me. My friend gives me entertainment without requiring any stipulation on my part. A friend, therefore, is a sort of paradox in nature. I who alone am, I who see nothing in nature whose existence I can affirm with equal evidence to my own, behold now the semblance of my being in all its height, variety and curiosity, reiterated in a foreign form; so that a friend may well be reckoned the masterpiece of nature.[...]I hate the prostitution of the name of friendship to signify modish and worldly alliances.

He returns to the greatest gift of true friendship:

[Friendship] is for aid and comfort through all the relations and passages of life and death. It is fit for serene days, and graceful gifts, and country rambles, but also for rough roads and hard fare, shipwreck, poverty, and persecution… We are to dignify to each other the daily needs and offices of man’s life, and embellish it by courage, wisdom and unity. It should never fall into something usual and settled, but should be alert and inventive, and add rhyme and reason to what was drudgery.

But Emerson argues, as I too have long believed, that the fruits of friendship are best harvested in one-on-one companionship rather than larger social situations. He explores the inverse correlation between the quality of connection and conversation and the number of friends involved:

I find this law of one to one, peremptory for conversation, which is the practice and consummation of friendship. Do not mix waters too much. The best mix as ill as good and bad. You shall have very useful and cheering discourse at several times with two several men, but let all three of you come together, and you shall not have one new and hearty word. Two may talk and one may hear, but three cannot take part in a conversation of the most sincere and searching sort. In good company there is never such discourse between two, across the table, as takes place when you leave them alone. In good company, the individuals at once merge their egotism into a social soul exactly co-extensive with the several consciousnesses there present. No partialities of friend to friend, no fondnesses of brother to sister, of wife to husband, are there pertinent, but quite otherwise. Only he may then speak who can sail on the common thought of the party, and not poorly limited to his own. Now this convention, which good sense demands, destroys the high freedom of great conversation, which requires an absolute running of two souls into one.

Returning to the building blocks of true friendship, Emerson points out that the most valuable friendships don’t spring from a filter bubble of like-mindedness but, rather, from the perfect osmosis of shared values and just enough discrepancy in tastes and sensibilities to broaden our horizons:

Friendship requires that rare mean betwixt likeness and unlikeness, that piques each with the presence of power and of consent in the other party… I hate, where I looked for a manly furtherance, or at least a manly resistance, to find a mush of concession. Better be a nettle in the side of your friend, than his echo. The condition which high friendship demands is ability to do without it… Let it be an alliance of two large formidable natures, mutually beheld, mutually feared, before yet they recognize the deep identity which beneath these disparities unites them.

(A phrase like “a mush of concession” reminds you of just how daring a writer Emerson was in his era, and how original he remains in ours.)

Illustration by Ben Shecter from 'The Hating Book' by Charlotte Zolotow, 1953. Click image for more.

He returns once more to the organic formation of true friendship and the reverie with which its natural rhythms should be beheld, the room we should give a friend to breathe and grow and just be:

Friendship demands a religious treatment. We talk of choosing our friends, but friends are self-elected. Reverence is a great part of it. Treat your friend as a spectacle. [Your friend] has merits that are not yours, and that you cannot honor, if you must needs hold him close to your person. Stand aside; give those merits room; let them mount and expand. Are you the friend of your friend’s buttons, or of his thought? To a great heart he will still be a stranger in a thousand particulars, that he may come near in the holiest ground…Leave this touching and clawing. Let him be to me a spirit.

To entrust a friend with the burden of our own wholeness, he suggests, is not only to place an unbearable weight on the relationship but also to relinquish vital personal responsibility:

We must be our own before we can be another’s… The least defect of self-possession vitiates, in my judgment, the entire relation. There can never be deep peace between two spirits, never mutual respect until, in their dialogue, each stands for the whole world.

Illustration by André François from 'Little Boy Brown,' a vintage ode to friendship by Isobel Harris. Click image for more.

Emerson ends by considering the dual art of what it takes to have a friend and to be one:

Wait, and thy heart shall speak. Wait until the necessary and everlasting overpowers you, until day and night avail themselves of your lips. The only reward of virtue, is virtue; the only way to have a friend is to be one.

A patience with the rhythms of relationships and an attentive sensitivity to their dynamics, he argues, will eventually elevate the true friendships over the false ones, over those of unequal investment of affections and effort, which will invariably fall away to reveal the immutable:

It has seemed to me lately more possible than I knew, to carry a friendship greatly, on one side, without due correspondence on the other. Why should I cumber myself with regrets that the receiver is not capacious? It never troubles the sun that some of his rays fall wide and vain into ungrateful space, and only a small part on the reflecting planet. Let your greatness educate the crude and cold companion. If he is unequal, he will presently pass away… But the great will see that true love cannot be unrequited. True love transcends the unworthy object, and dwells and broods on the eternal, and when the poor interposed mask crumbles, it is not sad, but feels rid of so much earth, and feels its independency the surer… The essence of friendship is entireness, a total magnanimity and trust.

Complement this with Andrew Sullivan’s beautiful reflections on friendship. Emerson’s Essays and Lectures includes equally insightful meditations on love, heroism, intellect, prudence, self-reliance, and more. The entire volume is available, and highly recommended, as a free download.

No comments:

Post a Comment