A new study concludes that modern humans arrived in Europe much earlier than previously believed, and that they may have overlapped with Neanderthals for as many as 5,400 years before the latter vanished. Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London explains the studies significance.

"Neanderthals Died Out 10,000 Years Earlier Than Thought, With Help From Modern Humans"

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/08/140820-neanderthal-dating-bones-archaeology-science/?google_editors_picks=true***

Modern Humans Arrived in Europe Earlier Than Previously Thought, Study Finds

Researchers Conclude Species Overlapped With Neanderthals for Long Period

Aug. 20, 2014

A new study concludes that modern humans arrived in Europe much earlier than previously believed, and clarifies more specifically the long time period they overlapped with Neanderthals.

The significant overlap bolsters a theory that the two species met, bred and possibly exchanged or copied vital toolmaking techniques. It represents another twist in an enduring puzzle about human origins: why we triumphed while the better adapted and similarly intelligent Neanderthals died out.

The study was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

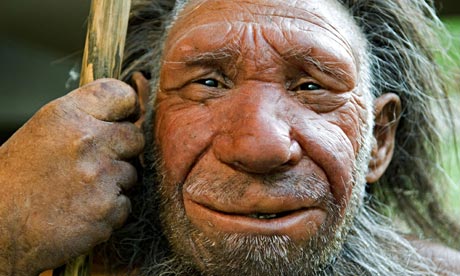

Neanderthals are our closest known extinct relatives, with about 99.5% of DNA in common with humans. They had a brain size similar to ours and much stronger bodies. They were also likely better adapted to Europe's bitter climate and had survived several ice ages. Modern humans, by contrast, arrived in Europe from sultry Africa.

Scientists have struggled to pinpoint when and how the Neanderthals disappeared in Europe. A big reason is that radiocarbon dating of material older than 30,000 years is unreliable because contamination of the samples can make them appear much younger.

An international team of scientists has now used improved techniques—including methods to remove contamination, plus more sophisticated chemical treatments—to more accurately date samples of bone, shell and charcoal dug up at 40 archaeological sites from Russia to Spain.

Neanderthals originally emerged from Africa and lived in Europe, Russia and the Middle East at least 200,000 years ago and possibly for tens of thousands of years before that.

Research suggests that modern humans first left Africa roughly 60,000 years ago and first headed eastward. Previous estimates have indicated that modern humans arrived in Neanderthal-dominated Europe about 40,000 years ago, and that some Neanderthals continued to persist in parts of the continent until just 32,000 years ago. Then they vanished, leaving the continent to humans.

The Nature study offers a significant revision of that timeline. It concludes that modern humans arrived considerably earlier—about 45,000 years ago—and that the two groups overlapped for anywhere from 2,600 years to 5,400 years before the Neanderthals died out.

Did the overlap mean that two groups in Europe met? Did they breed? Did they exchange or copy tools or other behaviors, a process known as "acculturation"? There is no hard evidence to answer those questions, but there are signs that some contact may have occurred.

For example, around 45,000 years ago, Neanderthal tools suddenly became more sophisticated and they also started to use symbolic artifacts such as body ornaments—just as Homo sapiens arrived in Europe.

"It's possible that the two groups met and that the Neanderthals copied humans in such behaviors, but we don't have any proof," says Sahra Talamo, a radiocarbon expert at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, who wasn't involved in the Nature study. "But another question is: who copied who?"

The study doesn't directly address the issue, but says there was "ample time for the transmission of cultural and symbolic behaviors, as well as possible genetic exchanges, between the two groups."

Even if the Neanderthals copied human technology, it remains a mystery why the better-adapted group died out while humans endured. Several factors could have contributed to their demise. They could have been out-competed by humans. The Neanderthal hunter-gatherers also may have lived in small groups scattered across Europe and were therefore cut off from one another.

"That presents a real problem for genetic diversity," which can significantly reduce the population and hurt a species' ability to survive, says Tom Higham, a radiocarbon scientist at the University of Oxford and a lead author of the Nature paper.

The Neanderthal legacy hasn't entirely vanished, though. In 2010, researchers showed that as much as 4% of the Neanderthal DNA survives in the genome of most people alive today—proof that the two groups mated and had offspring.

Chris Stringer of London's Natural History Museum notes that significant interbreeding had probably already occurred in the Middle East more than 50,000 years ago, "so the dating evidence now indicates that the two populations could have been in some kind of contact with each other for up to 20,000 years," first in the Middle East and then later in Europe.

Write to Gautam Naik at gautam.naik@wsj.com

No comments:

Post a Comment