Most Americans have little knowledge of farmers.

The following article is

enlightening.

***

Is the Risk of Suicide Higher for Farmers?

By Justin Rohrlich and Alex Brokaw May 10, 2012

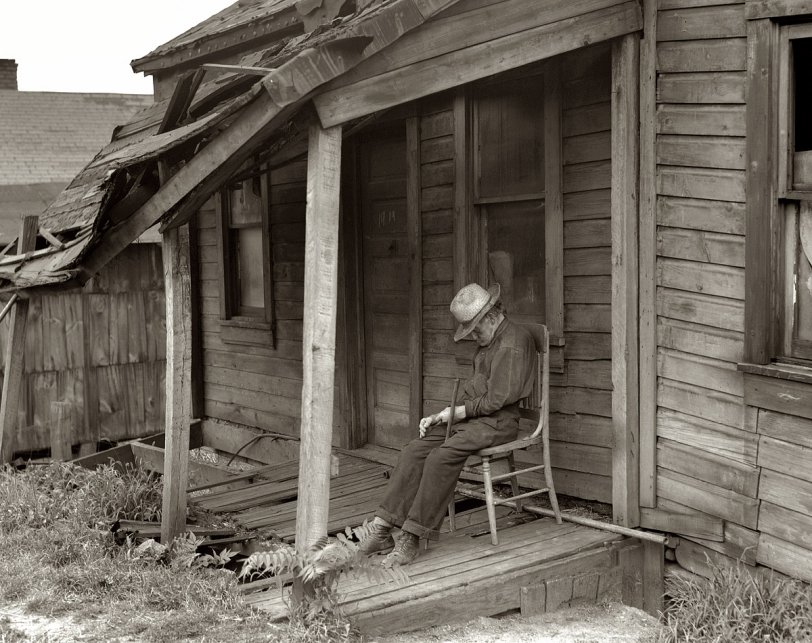

It's family farmers who are left exposed when the economy turns cloudy. The same 'frontier mentality' that has kept them hanging on for so long often holds them back from seeking help.

MINYANVILLE ORIGINAL

Stephen Diggle is bullish on farming.

The Singapore-based investor’s Vulpes Agricultural Land Investment Company, which currently owns corn farms in Illinois, and livestock and produce operations in Uruguay and New Zealand, announced plans to raise up to $150 million to expand operations into Africa and Eastern Europe.

“Yield-producing safe assets are intrinsically more interesting,” Diggle said in a recent interview.

Since 1935, the number of those yield-producing safe assets in the United States has gone from almost seven million to about two million. And, with fewer than 25% of all American farms earning gross revenues above $50,000, it’s family farmers -- not the Tysons (TSN) and Smithfields (SFD) of the world -- who are left exposed when the economy turns cloudy.

"I am convinced from evidence in our house that my husband listened to the grain markets on Monday at noon, as he usually did, heard them go lower again, and then committed suicide,” she explained.

Roger Hannan sits on the board of directors of the National Association for Rural Mental Health and provides mental health crisis outreach and intervention to farm and rural families in Illinois. He tells Minyanville that farmers today are “facing some of the same uncertainties as other business owners” in the US, but are not disproportionately at risk.

“I don’t see any major difference with the incidence of mental health crises on farms versus their town dwelling neighbors, maybe a little less,” Hannan says.

Dr. Eileen L. Fisher, PhD, Associate Director at the University of Iowa’s Center for Agricultural Safety and Health, has a different perspective.

She tells Minyanville, “Suicide rates for farmers in general are higher than the general population.”

Indeed, a 2004 Norwegian study of 17,295 adults found that male agricultural workers “had the highest level of depression of all occupational groups.” According to data compiled by R.J. Fetsch, professor of human development and family studies at the Colorado State University Extension, suicide has historically been “the most frequent external cause of death on farms and ranches.” And statistics show the suicide rate is higher among farmers than other occupations in the United States, as well as India, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

But why?

"The Agrarian Imperative," a 2010 paper by Michael R. Rosmann, PhD and published in theJournal of Agromedicine, “proposes a construct, the agrarian imperative, as an explanation for why people engage in agriculture.” Rosmann, a clinical psychologist and family farmer who is the Executive Director of AgriWellness, a non-profit organization that provides behavioral health services to “populations affected by rural crisis in agricultural communities,” suggests that “domesticating animals and cultivating land to produce food, fiber, and shelter allowed humans to proliferate.”

“In other words,” continues Rosmann, “agriculture yielded survival advantages for the human species. Genetic and anthropological evidence is accruing which suggests that acquiring territories of land to produce these necessities has an inherited basis which is encoded into our genetic material.”

However, while farming may be in our collective DNA, Dr. Rosmann’s research concludes that the “inability to farm successfully…is also associated with an increased probability of suicide.”

“The same traits that motivate farmers to be successful are associated with depression and suicide if their farming objectives aren't met,” Rosmann says.

Unfortunately, the higher prices many farmers have gotten for their output over the past couple of years have also increased input costs (higher beef prices offset by higher feed prices, for example), making “farming objectives” extremely difficult to meet.

One subset of the farming industry has suffered considerable hardship in the past few years -- dairy farming. Being a dairyman was recently ranked as the second-worst job in America on Careercast's 2012 “Worst Jobs List.”

"Physical labor, declining job opportunities, a poor work environment and high stress are all pervasive attributes," the description read.

Michael Marsh, CEO of Western United Dairymen in Modesto, California, confirms to Minyanville that “our farmers are under a great deal of stress.”

“Everyone’s chasing corn ethanol dollars now,” Marsh says. “Fall, 2008, there was a tremendous uptick in feed costs that raced right past the revenues farmers were generating and took away any profit margin they had. Then, around Christmas, we had the first producer in the state commit suicide down in the Hanford area.”

While Marsh believes the “rough economy will continue for the next couple of months,” he forecasts “some price relief going into the summer.”

“Our competitors in Australia and New Zealand dry their herds in winter,” Marsh explains. “As that milk supply goes off market, and as long as demand is there, I’m guessing our milk price will stay consistent going into the fall.”

That consistent price? Fourteen dollars per hundredweight, or 12 gallons. The problem is, it costs $18 to produce $14 worth of milk. Add to that a tight credit environment, and it becomes clearer why California has lost roughly 20% of its dairy farms since 2008.

“RaboBank is working with folks, American AgCredit, and a few others,” Marsh says. “Bank of America (BAC) is still involved in the processing side, though they’ve pulled out of the farming side. A lot of financial institutions are just really trying to avoid dairy in their portfolios.”

Some farmers have lived through this before. Others have chosen not to.

The higher incidence of suicide on farms is often tied to severe economic distress. After the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease and BSE, or mad cow, the suicide rate among British livestock producers went up by as much as 1,000%. As dairy prices cratered in 2008, calls to the Sowing the Seeds of Hope suicide help line, serving farmers in seven Midwestern states, jumped by 20%. Fourteen Colorado farmers and ranchers killed themselves, twice the number reported five years earlier. One shot himself dead following his banker’s warning to make his payments or risk “being cut off.”

Being “cut off” in a literal sense is troublesome for those living in isolated rural areas. Dr. Steven R. Kirkhorn, MD, MPH, Medical Director of the National Farm Medicine Center in Marshfield, Wisconsin, tells Minyanville that farm suicide “is an issue of concern, but one we are lacking data to adequately address the problem.”

“Depression in the farm community is under-reported, partially due to cultural issues of self-reliance and just as importantly, lack of access to behavioral health specialists,” Kirkhorn says. “This is an issue that is not addressed satisfactorily by any Agricultural Health or Safety Center that I am aware of and the assessment and care is scattered throughout the rural area. Many of those who need help don’t have insurance that will cover behavioral health services and if they do, the waiting times may be months to be seen.”

Beyond a dearth of accessible care, the cultural issues Kirkhorn mentions are significant.

Western United’s Michael Marsh believes the “frontier mentality” to which many modern farmers still subscribe is a key component.

“It’s that mindset of, ‘Me against the elements and we’re gonna be survivors'," he says. "Let’s say your farm operation started in your family in 1880s and stayed in [the] family all these years. It comes to 2010 and you’re the generation that loses the family legacy. Your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents built it, and here you have the business and all these beautiful animals and barns and milking parlors and employees and then, one day, it’s gone. It’s pretty easy to see how depressing that might be.”

It’s a theory shared by Michael Rosmann, who, in a 2003 conference presentation to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, noted:

Further, some maintain the pesticides farmers use are causing behavioral issues leading to suicides down the line.

From the December, 2008 edition of Environmental Health Perspectives, a peer-reviewed journal from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences:

They write:

Ultimately, though the suicide rate among farmers is demonstrably higher in most parts of the world, some accounts can paint an inaccurate picture of an “epidemic,” rather than a steady, elevated state that must be addressed. Ron Herring, a professor of government at Cornell University, interviewed Indian farmers in 2006 after 200,000 suicides in 10 years.

He called "the media construction baseless," and told the Cornell Chronicle, “Farmers were insulted and incredulous: If farmers committed suicide every time they fell into debt, they said, there would be no farmers.”

What does the future hold for the hard-working men and women who put food on our plates? The USDA Economic Research Service has food prices up across the board, year-over-year. Milk, on the other hand, is expected to stay below the 2011 price. Still, John Frey, Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Center for Dairy Excellence, has a decidedly optimistic forecast.

“2012 will be a historic year,” he tells Minyanville. “We are going to produce 200 billion pounds of milk for the first time ever.”

Frey points out that it took the dairy industry -- which trades milk by weight, not volume -- 62 years to go from 100 billion pounds to 150 billion, but only 20 years to reach 200 billion from 150 billion.

“The average person might wonder, ‘Where does all of this milk go?’” he says. “Well, can you say Greek yogurt? Can you say new varieties of low fat fluid milk? And don’t forget, Americans have an insatiable appetite for cheese.”

2010 and 2011 were good years for milk and Frey admits to a bit of excess supply currently in the market.

“So, here we are in 2012 and we do have a slight imbalance of supply and demand,” he says. “Margins are certainly forecast to be significantly lower, perhaps by as much as one-third, and it’s going to be a year of pulling back in our industry.”

With that said, Frey is certain all will be okay. He rightfully describes the dairy business as “an incredible business with incredible people” and says he is “nothing short of amazed at how our industry came through in 2009.”

“Though, of course,” he adds, “we certainly hope that it doesn’t result in any similar tragedies like we saw then.”

Stephen Diggle is bullish on farming.

The Singapore-based investor’s Vulpes Agricultural Land Investment Company, which currently owns corn farms in Illinois, and livestock and produce operations in Uruguay and New Zealand, announced plans to raise up to $150 million to expand operations into Africa and Eastern Europe.

“Yield-producing safe assets are intrinsically more interesting,” Diggle said in a recent interview.

Since 1935, the number of those yield-producing safe assets in the United States has gone from almost seven million to about two million. And, with fewer than 25% of all American farms earning gross revenues above $50,000, it’s family farmers -- not the Tysons (TSN) and Smithfields (SFD) of the world -- who are left exposed when the economy turns cloudy.

"The only thing I will regret is leaving the children and you. This farming has brought me a lot of memories, some happy, but most of all grief. The grief has finally won out -- the low prices, bills piling up, just everything. The kids deserve better and so do you. I just don't know how to do it. This is all I know and it's just not good enough anymore. I'm just so tired of fighting this game, because it is a losing battle. Everything is gone, wore out or shot, just like me.”That’s what an Iowa farmer wrote to his wife before he killed himself in 1999. Currently the US Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, was the Governor of Iowa at the time. He shared the letter -- and a note from the farmer’s widow, whose identity was kept private -- at that year’s National Governors’ Meeting.

"I am convinced from evidence in our house that my husband listened to the grain markets on Monday at noon, as he usually did, heard them go lower again, and then committed suicide,” she explained.

Roger Hannan sits on the board of directors of the National Association for Rural Mental Health and provides mental health crisis outreach and intervention to farm and rural families in Illinois. He tells Minyanville that farmers today are “facing some of the same uncertainties as other business owners” in the US, but are not disproportionately at risk.

“I don’t see any major difference with the incidence of mental health crises on farms versus their town dwelling neighbors, maybe a little less,” Hannan says.

Dr. Eileen L. Fisher, PhD, Associate Director at the University of Iowa’s Center for Agricultural Safety and Health, has a different perspective.

She tells Minyanville, “Suicide rates for farmers in general are higher than the general population.”

Indeed, a 2004 Norwegian study of 17,295 adults found that male agricultural workers “had the highest level of depression of all occupational groups.” According to data compiled by R.J. Fetsch, professor of human development and family studies at the Colorado State University Extension, suicide has historically been “the most frequent external cause of death on farms and ranches.” And statistics show the suicide rate is higher among farmers than other occupations in the United States, as well as India, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

But why?

"The Agrarian Imperative," a 2010 paper by Michael R. Rosmann, PhD and published in theJournal of Agromedicine, “proposes a construct, the agrarian imperative, as an explanation for why people engage in agriculture.” Rosmann, a clinical psychologist and family farmer who is the Executive Director of AgriWellness, a non-profit organization that provides behavioral health services to “populations affected by rural crisis in agricultural communities,” suggests that “domesticating animals and cultivating land to produce food, fiber, and shelter allowed humans to proliferate.”

“In other words,” continues Rosmann, “agriculture yielded survival advantages for the human species. Genetic and anthropological evidence is accruing which suggests that acquiring territories of land to produce these necessities has an inherited basis which is encoded into our genetic material.”

However, while farming may be in our collective DNA, Dr. Rosmann’s research concludes that the “inability to farm successfully…is also associated with an increased probability of suicide.”

“The same traits that motivate farmers to be successful are associated with depression and suicide if their farming objectives aren't met,” Rosmann says.

Unfortunately, the higher prices many farmers have gotten for their output over the past couple of years have also increased input costs (higher beef prices offset by higher feed prices, for example), making “farming objectives” extremely difficult to meet.

One subset of the farming industry has suffered considerable hardship in the past few years -- dairy farming. Being a dairyman was recently ranked as the second-worst job in America on Careercast's 2012 “Worst Jobs List.”

"Physical labor, declining job opportunities, a poor work environment and high stress are all pervasive attributes," the description read.

Michael Marsh, CEO of Western United Dairymen in Modesto, California, confirms to Minyanville that “our farmers are under a great deal of stress.”

“Everyone’s chasing corn ethanol dollars now,” Marsh says. “Fall, 2008, there was a tremendous uptick in feed costs that raced right past the revenues farmers were generating and took away any profit margin they had. Then, around Christmas, we had the first producer in the state commit suicide down in the Hanford area.”

While Marsh believes the “rough economy will continue for the next couple of months,” he forecasts “some price relief going into the summer.”

“Our competitors in Australia and New Zealand dry their herds in winter,” Marsh explains. “As that milk supply goes off market, and as long as demand is there, I’m guessing our milk price will stay consistent going into the fall.”

That consistent price? Fourteen dollars per hundredweight, or 12 gallons. The problem is, it costs $18 to produce $14 worth of milk. Add to that a tight credit environment, and it becomes clearer why California has lost roughly 20% of its dairy farms since 2008.

“RaboBank is working with folks, American AgCredit, and a few others,” Marsh says. “Bank of America (BAC) is still involved in the processing side, though they’ve pulled out of the farming side. A lot of financial institutions are just really trying to avoid dairy in their portfolios.”

Some farmers have lived through this before. Others have chosen not to.

The higher incidence of suicide on farms is often tied to severe economic distress. After the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease and BSE, or mad cow, the suicide rate among British livestock producers went up by as much as 1,000%. As dairy prices cratered in 2008, calls to the Sowing the Seeds of Hope suicide help line, serving farmers in seven Midwestern states, jumped by 20%. Fourteen Colorado farmers and ranchers killed themselves, twice the number reported five years earlier. One shot himself dead following his banker’s warning to make his payments or risk “being cut off.”

Being “cut off” in a literal sense is troublesome for those living in isolated rural areas. Dr. Steven R. Kirkhorn, MD, MPH, Medical Director of the National Farm Medicine Center in Marshfield, Wisconsin, tells Minyanville that farm suicide “is an issue of concern, but one we are lacking data to adequately address the problem.”

“Depression in the farm community is under-reported, partially due to cultural issues of self-reliance and just as importantly, lack of access to behavioral health specialists,” Kirkhorn says. “This is an issue that is not addressed satisfactorily by any Agricultural Health or Safety Center that I am aware of and the assessment and care is scattered throughout the rural area. Many of those who need help don’t have insurance that will cover behavioral health services and if they do, the waiting times may be months to be seen.”

Beyond a dearth of accessible care, the cultural issues Kirkhorn mentions are significant.

Western United’s Michael Marsh believes the “frontier mentality” to which many modern farmers still subscribe is a key component.

“It’s that mindset of, ‘Me against the elements and we’re gonna be survivors'," he says. "Let’s say your farm operation started in your family in 1880s and stayed in [the] family all these years. It comes to 2010 and you’re the generation that loses the family legacy. Your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents built it, and here you have the business and all these beautiful animals and barns and milking parlors and employees and then, one day, it’s gone. It’s pretty easy to see how depressing that might be.”

It’s a theory shared by Michael Rosmann, who, in a 2003 conference presentation to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, noted:

“To farmers, ‘the land is everything.’ Ownership of a family farm is the triumphant result of the struggles of multiple generations. Losing the family farm is the ultimate loss -- bringing shame to the generation that has let down their forbearers and dashing the hopes for successors.”Of course, farmers also have ready access to guns and other lethal means; chillingly, Australia’s National Centre for Farmer Health asserts, “Sometimes what looks like a ‘farm accident’ is actually a suicide.”

Further, some maintain the pesticides farmers use are causing behavioral issues leading to suicides down the line.

From the December, 2008 edition of Environmental Health Perspectives, a peer-reviewed journal from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences:

“A study of farmers finds that those with the highest number of lifetime exposure days to agricultural pesticides were 50% more likely to be diagnosed with clinical depression than those with the fewest application days and were 80% more likely if they had applied a class of insecticide called organophosphates.”Organophosphates, which are contained in many common agricultural insecticides like Dursban from Dow AgroScience (DOW) and Aztec from American Vanguard (AVD), are also fingered as substances that can lead to depression -- and ultimately, suicide -- by AgriWellness’ Michael Rosmann and Dr. Lorann Stallones, MPH, PhD, an epidemiologist at Colorado State University.

They write:

“Many healthcare practitioners, even those in agricultural areas, are not aware that organophosphate and carbamate insecticide poisoning can lead to depression. There are established links between acute poisoning from organophosphate compounds and increased risk of suicide.Amazingly, it is even suggested that treating depression resulting from pesticide poisoning with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (i.e. Prozac (LLY), Zoloft (PFE), Paxil (GSK),Celexa (FPI), and Luvox (JAZZ)) may actually increase the risk of suicide.

“Acute exposures to organophosphates and carbamates produce headache, nausea, muscle twitching, diarrhea, excessive salivation and sweating, difficulty breathing and severe exposures can lead to pulmonary edema, seizures and death.”

Ultimately, though the suicide rate among farmers is demonstrably higher in most parts of the world, some accounts can paint an inaccurate picture of an “epidemic,” rather than a steady, elevated state that must be addressed. Ron Herring, a professor of government at Cornell University, interviewed Indian farmers in 2006 after 200,000 suicides in 10 years.

He called "the media construction baseless," and told the Cornell Chronicle, “Farmers were insulted and incredulous: If farmers committed suicide every time they fell into debt, they said, there would be no farmers.”

What does the future hold for the hard-working men and women who put food on our plates? The USDA Economic Research Service has food prices up across the board, year-over-year. Milk, on the other hand, is expected to stay below the 2011 price. Still, John Frey, Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Center for Dairy Excellence, has a decidedly optimistic forecast.

“2012 will be a historic year,” he tells Minyanville. “We are going to produce 200 billion pounds of milk for the first time ever.”

Frey points out that it took the dairy industry -- which trades milk by weight, not volume -- 62 years to go from 100 billion pounds to 150 billion, but only 20 years to reach 200 billion from 150 billion.

“The average person might wonder, ‘Where does all of this milk go?’” he says. “Well, can you say Greek yogurt? Can you say new varieties of low fat fluid milk? And don’t forget, Americans have an insatiable appetite for cheese.”

2010 and 2011 were good years for milk and Frey admits to a bit of excess supply currently in the market.

“So, here we are in 2012 and we do have a slight imbalance of supply and demand,” he says. “Margins are certainly forecast to be significantly lower, perhaps by as much as one-third, and it’s going to be a year of pulling back in our industry.”

With that said, Frey is certain all will be okay. He rightfully describes the dairy business as “an incredible business with incredible people” and says he is “nothing short of amazed at how our industry came through in 2009.”

“Though, of course,” he adds, “we certainly hope that it doesn’t result in any similar tragedies like we saw then.”

Read more: http://www.minyanville.com/business-news/editors-pick/articles/commodities-commodity-prices-farming-family-farms/5/10/2012/id/40924#ixzz1uUHikT1j

No comments:

Post a Comment