|

(Photo: Danny Kim/New York Magazine)

When the governor of Michigan ran for the Republican nomination, in 1968, he tried to stand up against the more radical wing of his party. His defeat was swift, tragic, and, for his son, instructive. |

You could say that the end of the moderate-Republican Establishment—the days when the smoke-filled rooms started to empty of father figures, and the casual country-club banter was replaced by something angrier—began at the party’s 1964 convention, at the Cow Palace, just south of downtown San Francisco, a week that ended with Barry Goldwater nominated for president. Political revolutions are often apparent only in retrospect, but this one was obvious to everyone right away, as if some great national timing mechanism had been involved. The conservatives, arriving and feeling triumphant, gave the event an explosive, adolescent, rumspringa energy.

This atmosphere was alarming enough to George Romney, the governor of Michigan, that he arrived a few days early, to support an amendment to the official party platform that would denounce extremism of all types. After his testimony, which also included support for an enhanced civil-rights amendment, Romney found himself in conversation with a leading southern delegate. Romney’s amendment, the delegate explained, was a nonstarter. He “made it clear that there had been a platform deal that was a surrender to the southern segregationists,” Romney later wrote in a furious letter to Goldwater. Romney was too late. The trajectory of the party had already been arranged.

The feeling of right-wing ascendance was almost physical. Some young moderates compared the atmosphere to a Nazi rally. “The booing, the hissing—it was frightening,” says Walter De Vries, who was Romney’s chief political strategist. Dwight Eisenhower, who just four years earlier had been president and was still the moderates’ icon, would later tell reporters that his niece had been “molested” on the convention floor; the plutocratic New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, trying to give a speech condemning right-wing extremism, was booed and catcalled until no one could hear him. (Rockefeller, characteristically, gave as good as he got.) Romney’s camp had long regarded Michigan’s conservatives as provincial unmentionables, deeply angry men who showed up at state conventions armed with megaphones, trying to shout the governor down. But clearly they had figured something out. In his acceptance speech, Goldwater confirmed their power. “Extremism in the defense of liberty,” he said famously, “is no vice.”

The convention was, of course, not really anything like a Nazi rally, but the comparison suggests something about how essential the moderates believed their fight to be. It was obvious to them—in some cases for the last time in their political careers—exactly who was right and who was wrong. “With such extremists rising to official positions of leadership in the Republican party, we cannot recapture the respect of the nation and lead it to its necessary spiritual … and political rebirth,” Romney said. He walked out of his own party’s convention, taking with him De Vries and his 17-year-old son Mitt, and became, in that moment, a candidate for president in 1968. He also became an idea of himself—the tragic, alienated moderate Republican, a character he would spend nearly a decade performing, until, in 1972, he resigned from the Nixon administration and more or less retired from public life.

The matter of what, exactly, happened to George Romney, and what became of the progressive Republican tradition he embodied, has ghosted into the current presidential campaign, in which his own image has been overlaid with that of his son Mitt—taller and less blockily built, but the same jaw, the same hair, the same gestures, the same ringing, pressured manner of speech, caught in a similarly uneasy negotiation with conservatives. When Mitt Romney declared his candidacy for the presidency for the first time, in 2007, it was in Michigan, a state in which he’d never had a public role, in front of a Rambler, the compact car that was the triumph of his father’s business career, not his own. Politics had never preoccupied Mitt Romney growing up, and his family was surprised he had sought office at all; there is the hint that he only became a politician to complete his father’s legacy. “My dad is Mitt’s hero,” G. Scott Romney, Mitt’s older brother, told me. “And, look, I think my brother’s an exceptional person. But Mitt has said he’s a shadow of his father.”

De Vries was friends with the late, legendary Washington Post political reporter David Broder, and in 2007 spent much of his time researching a book he planned to write, with Broder’s help, about Mitt Romney, through the lens of his father’s politics. He gave the manuscript the working title Governors George and Mitt: Like Father, Like Son. But during the 2008 campaign, as De Vries was working on the manuscript, it began to occur to him that the attributes that had once drawn him to George were not so apparent in his son. The almost sacramental faith in the institutions of American life; the moral convictions so clear they frequently became rigid; the almost physical charisma—somehow none of that had survived.

One day, De Vries sat down at his computer and, with no clear precipitating cause, deleted the manuscript’s title. In its place, feeling peevish, he typed in a new one, The Political Mitt Romney: Not His Father’s Son. Then he called Broder, and told him that his thesis needed to change.

|

Romney visiting Chicago, accompanied by his wife, in September 1967.

(Photo: Edward Kitch/AP)

|

The nostalgia for the progressive paternalism of Rockefeller and Romney is deep and sometimes desperate, particularly now, given the conservative grip on Republican politics. One way of viewing the 1968 election, the view that De Vries inclines toward, is as the moment when the conservative faction prevailed over George Romney’s progressivism, so fully converting the party to an individualist view of society that even Romney’s own son now embraces it.

But the story of the 1968 election is more complicated than that. The moderate Establishment wasn’t just attacked; it also collapsed from within. Faced with the crises of the late sixties, Romney turned repeatedly to the Establishment he believed in, only to find it had no solutions to offer. The effect of the ghost on Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign may not only be to supply a political ideal to which he can’t measure up, but to have created for him a vision of politics that long ago became impossible.

Spring, 1967.

As he began his presidential campaign, George Romney had never held office outside the state of Michigan and had rarely had to think about international affairs. When policy questions were made tangible, he could handle them nimbly, but he sometimes struggled when they grew more abstract. There were, everyone on his staff acknowledged, certain gaps.

And so in the spring of 1967, De Vries scheduled a series of weekend seminars, importing experts to meet with the governor at his summer home on rustic, carless Mackinac Island. The Romney camp had hired a young foreign-policy aide named Jonathan Moore, who one Friday evening arrived at the ferry dock to collect Henry Kissinger, and with him the machinery of the modern presidential campaign. They were to return to the Romney home on a horse and buggy, and Moore signaled Kissinger over; the horse released a “warm, moist” fart right into the professor’s face. “Kissinger gave a little cough,” Moore says, “and then sort of looked off into the distance and said, ‘I see we have a lot of ground to cover.’ ”

Ever since the 1964 convention, the Republican Party’s elders had tried to persuade Romney and Goldwater to reconcile, as a step toward reuniting the party’s progressives and conservatives. What they got instead was a catalogue of picayune slights and feuds and a growing ideological distance, a kind of nuclear-arms race in the arena of epistolary dictation to secretaries. For months the two men sniped at each other by letter, extending and then retracting invitations to meet, taking offense at tiny snubs. Romney drafted a statement disavowing extremists that he insisted Goldwater sign; Goldwater refused. Let’s “ask ourselves,” the conservative wrote to Romney, “who it was in the party who said, in effect: ‘If I can’t have my way, I’m not going to play?’ One of these men happens to be you.”

This feud revealed the shape of the party as 1968 approached—there would be a conservative candidate and a progressive one, and it was obvious early on that the progressive would be Romney. Rockefeller had given Romney his backing at the Dorado Beach Hotel in Puerto Rico, pledging significant northeastern support and offering the use of his policy staff.

In Michigan, particularly to the young men who clustered around him, George Romney seemed to embody the party’s future. “He was so atypical, so fresh,” De Vries says, “that he made the other Republicans seem gloomy by comparison.” Romney had the classic Republican convictions—enthusiasm for the market and for a less intrusive federal government, and a moral core to his politics. The labor-backed Democratic Party, for him, “was politically corrupt, morally wrong, economically unsound, and socially indefensible.” When he ran for office it was always as a modernizer. In 1963, President Kennedy had confided to his close friend Paul Fay, “The one fellow I don’t want to run against is Romney.”

But from his first campaign in Michigan, Romney downplayed his partisan affiliation. His first great fight was to successfully reform Michigan’s constitution, giving the state the right to tax more broadly, adding civil-rights protections, and reallocating political power from rural areas to the growing cities. His approach could be theatrical: He would barge into labor parades and union plants, environments where he was politically least welcome. When the young civil-rights activist Viola Liuzzo was killed in Alabama, he stomped to her Detroit door and told her family her death reminded him of Joan of Arc’s; he demonstrated for housing integration in Grosse Pointe. I mentioned to an old Romney aide named Bill Whitbeck that Romney seemed awfully willful. “Willful is kind of a weak word,” he said, and took a minute to think of another one. “Messianic,” he finally offered. “This guy was John Brown.”

|

The governor, guarded by an armed policeman as he tours the scene of the Detroit riots in July 1967.

(Photo: AP)

|

The messianic figure for the conservatives was already apparent in 1967: Ronald Reagan. But Reagan had been governor of California for less than a year and was adamant he would not run, so the most powerful force in the party had no natural champion. It did, however, have the former vice-president, a mainstream man who nonetheless saw where the wind was blowing. Nixon, one Republican insider had told David Broder, “is trying to take the remnant of this Goldwater thing and give it some respectability.”

When Nixon first organized his aides to plan his campaign, at the Waldorf Towers in New York, he laid out the odds, as he saw them. Romney was even money for the nomination; the odds against himself, Nixon said, were two to one. The opportunity lay in the South; he and his advisers counted up the delegates they might collect there and determined a southern-based strategy would be enough.

Nixon may not have been a perfect ideological fit for his supporters, but then Romney was a misfit, too. In place of the lived-in, slightly cynical centrism of the Eastern elite, Romney had an idealism about the country and its institutions that only an outsider could manage. Romney was terrible at jokes and didn’t even try to tell them, diverting instead into homilies. He possessed, Theodore H. White wrote, “a sincerity so profound that, in conversation, one was almost embarrassed”; his politics, another writer noticed, “sounded more religious than the average Mormon sermon.” Nixon, ever shrewd, was convinced that at some point in the campaign Romney’s support would buckle as Easterners eventually tired of him.

As the national campaign arrived in Michigan, the Romneyites started to feel their own difference—a cultural earnestness that might seem anachronistic, an idealism that others might no longer feel. “I felt like I was on some planet that I’d never known existed,” Moore says. At one evening seminar, Moore watched the governor ask Kissinger if he wanted a drink. Kissinger did. The governor had a little sideboard where he kept the alcohol, strictly for guests. Moore watched him, fumblingly, pour a glass that must have been 80 percent booze, a little bit of water splashed over the top. Romney extended the tumbler. Kissinger gave a tense grin and, after a second, accepted it.

If you forget for a moment the scrim of weirdness that shades even the word Mormon—the underwear, the rites, the space-alien temples, the fact that before a 19-year-old George Romney was sent on his mission he was taken inside the Salt Lake City temple and stripped and doused with anointing oils—what you are left with is a system of belief in which America itself is hallowed. Not just the abstract ideas of freedom, liberty, and self-determination, but the design of the country is believed by Mormons to be divinely inspired: the Constitution, the separation of legislative and executive powers, even the structure of the American corporation. Jesus appeared, in the Mormon tradition, not in Jerusalem or Rome but upstate New York. The most mundane spots on the map of American suburban sprawl are empowered and made holy: Palmyra, New York; Kirtland, Ohio; Nauvoo, Illinois.

Until early in the twentieth century, Mormons had a unique, supplicating position toward the United States: They believed the country had been touched by God, and it disdained them as members of a dangerous sect. It was in George Romney’s generation—and this is in some ways the story of George Romney’s own life—that Mormon culture remade itself, from an outlaw sect into the most buoyantly, enthusiastically American thing going.

George Romney was born in 1907 in a Mormon colony in Mexico, where his grandfather had moved the family two decades earlier after the American government outlawed polygamy. (George’s parents were monogamous.) Around his 5th birthday, the colony was ransacked by Mexican revolutionaries, and the family, returning to the U.S., effectively became nomads while his father chased work as a builder. By the time he was in the sixth grade, George had attended six elementary schools; the lowest point came in Idaho, when the family’s failed attempt at potato farming barely got them through the year. As a 12-year-old, George was already doing hard agricultural work, trimming the tops of sugar beets by hand.

In Romney’s papers, archived in the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, there is a long reminiscence he wrote about a trip he took back to the Mormon West with his father. George was 34 and already a success, and his essay reveals a tender nostalgia for rougher times. He recalled the polygamist families he’d known as a boy—the practice was “repugnant,” but the families had “high character” and “unity.” He visited the Mormon temple in St. George, Utah, and pronounced it as stylish as the White House. Traveling with his father, he thought about how frequently his family had been in “great distress,” and how infrequently he had realized this at the time.

|

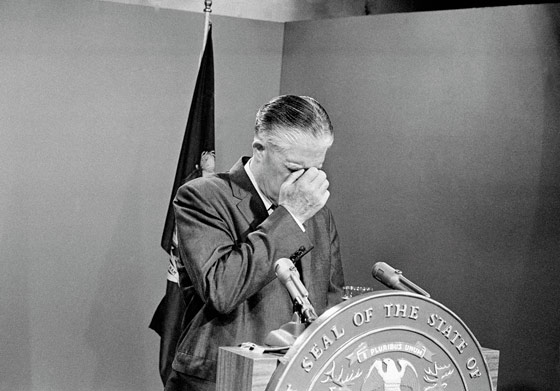

A moment of meditation before speaking live on television about the riots.

(Photo: Alvan Quinn/AP)

|

Mormons earn salvation, in part, through their deeds, and in this respect the religion is more like Catholicism than Protestantism. When scholars explain the extreme success some Mormons have had in business, they tend to emphasize this feature. But Matthew Bowman, a young historian at Hampden-Sydney College and the author of The Mormon People, thinks there is another implication, too. Institutions have an essential place in Mormon thought; they are the mechanisms by which the individual is transformed. In Romney’s private correspondence this theme is vivid: Asked repeatedly by young men for his advice, he suggests they dedicate themselves to their church, to their professional organizations, to volunteerism. This was the sustaining idea of his life—that buying in would bring rewards.

There was always a purposefulness about Romney, an intensity to his ascent up the social ladder. At 17, he fell in love with Lenore LaFount, the strikingly beautiful daughter of a successful Mormon businessman. (One day, she would be offered a studio contract by MGM.) His pursuit was assiduous. In Scotland, serving a church mission, he deflected accusations that the Mormons were out to steal Scottish lassies by brandishing a picture of Lenore; rather than finishing college, he followed her to Washington, D.C., and took a job as a stenographer in Senator David Walsh’s office to prove his dedication.

This won him Lenore (they would be married 64 years, and each morning he would place a fresh rose by her bedside); it also gave him a career. Soon, the Walsh job became a substantive staff position working on tariff policy, and from there he moved into a career as a lobbyist with Alcoa, and then went into the automotive industry. Three decades after his family went bust farming potatoes, Romney was overseeing Detroit’s work for the war effort, and this, too, had for him an Evangelical tone; by 1942 he was sending enthusiastic dispatches back to church headquarters detailing the “many miracles” he was watching American industry achieve.

After the war, Romney was hired as an assistant to the president of what would become American Motors, and eventually became president himself. By the late fifties, convinced that Detroit was betting too heavily on expensive, unnecessarily large cars, Romney committed his company to a smaller, cheaper, more efficient model, the Rambler, and the resulting success landed him on the cover of Time. In front of Congress, he testified against the concentration of power in large companies and unions; in Detroit, he built the beginnings of a political career, working to reform the city’s schools and, eventually, the Michigan constitution.

What was taking shape was his vision of a perfect society, one in which government need not intervene because the “independent sector”—community organizations, professional and religious groups, and American businesses—could fix social problems on their own. Whenever they were detailing a solution to a policy problem, Romney’s aides learned to look first to these groups before turning to the government. He believed “that these contexts would help the individual, that they would give meaning,” says De Vries. No one, after all, is more invested in a good elite than the outsider who has had to work to join it. “I think he believed that America would always work,” De Vries says, “because America had always worked for him.”

Summer, 1967.

The riot started Sunday at dawn in Detroit, July 23, 1967, after police tried to raid an unlicensed after-hours club, but it took several hours before it was clear that the crowds that gathered there, throwing bottles at the cops, were not going away. Romney’s aides were soon driving down Interstate 696 from Lansing to Detroit, and as Bill Whitbeck arrived the streets were almost empty of cars. “Eerie,” he remembers. From the freeway he could see smoke rising from the West Side, where the conflict had begun, but also from the East. As another group of aides inched along, trying to navigate the roadblocks, they noticed that the looting seemed strategic—some stores had been left alone while others on the same block had been emptied entirely. “We observed that we were the only white men in the area, driving,” they would write in a memo. “We decided that it would be to our advantage to leave the vicinity as soon as possible.”

Romney had been at home in Bloomfield Hills that first day, working on a foreign-policy speech, but in the evening he took a helicopter flight over the city to get a feel for the scale of the damage. The fires had spread over an area of eight square miles. Romney had asked a contingent of National Guardsmen to deploy to Detroit and stand by, but it wasn’t clear whether these forces could contain the violence. When he held a press conference with the Detroit mayor after midnight, the two officials told reporters that “the difficulty” now consumed 139 square miles, and Romney told reporters he had called the attorney general to request federal reinforcements. “It is the only prudent thing to do,” he said. But it was Lyndon Johnson’s attorney general, and Romney was a political threat, and so Washington seemed to delay: First, Romney was told the request needed to be in writing; then, when he sent a telegram, that he had used the wrong language. Romney, furious, was convinced that the Democratic White House was cynically stalling.

The city continued to burn. What would come to characterize the Detroit riots—and make them uniquely terrifying—was the presence of a novel figure, the radical black sniper. Two days into the riots, a group of 40 National Guardsmen and police were pinned down at Ford Hospital by snipers. A 51-year-old white woman named Helen Hall, visiting Detroit on business, was shot through the window of the Harlan House Motel. It now appears likely she was actually killed by a Guardsman’s errant bullet, but the cops at the time insisted it was a sniper with a deer rifle.

The imagery of Vietnam was replicating itself; for a few days, the ghetto really was a war zone. To Nixon, the implications were clear. “We must take the warnings to heart,” he would later declare, “and prepare to meet force with force if necessary.” The reaction to the riots, in his hands, was an incubator for the politics of white backlash. To court conservative voters, Nixon could play “the white side’s field marshal,” as the historian Rick Perlstein writes in Nixonland. In private, the former vice-president was negotiating with Senator Strom Thurmond the terms of Southern influence within the party—his White House would not oppose integration, but neither would it implement it speedily. In public, the riots allowed him to focus racial anxieties on something more immediate: the fear of violence. Nixon would tell a national radio audience, “our first commitment as a nation in this time of crisis and questioning must be a commitment to order.”

Romney’s perspective was different, and his reaction to the riots far more fraught. The governor had spent years working to improve Detroit’s black inner city, to incorporate it, to give it access to the broader society. Though his church refused to ordain black clergymen until 1978, Romney was deeply committed to civil rights and clearly felt a bond with members of another persecuted minority. One of his great causes was the integration of the suburbs (his aides called it the “Romney Right to Walk to Work Program”), so blacks could join the middle class, too.

But the black middle class itself was revolting. When Romney staffers drove through Detroit during the riots, they noticed that “the looting and the fire bombing was supported by a number of middle-income Negroes.” The black homeowners they interviewed refused to intervene; the black ministers they encountered blamed the extortionate practices of the burned businesses. Blacks were repudiating Romney’s buy-in from the left, just as Nixon was repudiating it from the right. Driving toward Woodward Avenue, on the city’s West Side, the staffers noticed that many buildings had signs written on them, in chalk or paint: “Soul Brother lives upstairs. Please do not burn.” “Soul Brother. Do Not Burn.” Then, simply: “Soul Brother.”

It took about a week for the violence to dissipate, once the troops sent by Washington finally arrived. Forty-three people were killed in the rioting; hundreds of stores were looted. Romney was, first, furious at the White House. His second reaction, De Vries says, was deeper: “I think he had a hard time explaining why this had happened.”

Fall, 1967.

On August 31, one month after the riots, Romney showed up at a Detroit television station for an interview on The Lou Gordon Program, which mattered quite a lot locally and not much at all to anyone else. The summer had both preoccupied and diminished him. When he could get away from Michigan, Romney was focusing on small campaign events where the force of his personality might move a few votes. Nixon, meanwhile, was running a brilliant mass-media campaign, soon to be orchestrated by his aide Roger Ailes—“no baby-kissing, no handshaking, no factory gates,” Nixon said. At the beginning of the year, the race had been a dead heat; now Romney was eleven points behind.

Romney had been devoting his attention to the wrong cataclysm. The race riots were important, their political aftereffects profound. But the crisis that the news reporters kept returning to—the question that for them defined who could handle the presidency—was not the riots but Vietnam, and here Romney had less familiarity, and even less clarity. On the eve of a big Vietnam speech, unsure of himself, he’d sent the draft to Rockefeller for approval. Now, as he trudged from doorstep to doorstep, the governor’s Vietnam position was still “unresolved,” Moore says. Reporters had noticed. At the taping that day, Gordon asked whether Romney had changed his position since 1965, when he had just returned from a rushed governors’ trip to Vietnam, when he said the intervention in Vietnam was “morally right.”

Romney moralized everything; whether something was morally right was the question that interested him the most. That trip, back when the war was smaller and still dimly understood, when the governor had pinned Purple Hearts on wounded soldiers, had convinced him to support the president. In the years since, his doubts had coalesced—as Johnson tried to bully him into support, as figures like Martin Luther King Jr. issued denunciations—and he was becoming “more and more convinced that the war was a mistake,” says Moore. “And yet he had this patriotic instinct he had to get past.”

Somehow that resistance broke on The Lou Gordon Program. In Vietnam, Romney told the host, referring to his 1965 trip, “I just had the greatest brainwashing that anybody can get … Not only by the generals, but also by the diplomatic corps over there, and they do a very thorough job.” More recently, he had “gone into the history of Vietnam, all the way back into World War II and before, and as a result I have changed my mind … I no longer believe that it was necessary for us to get involved in South Vietnam.” He went on, issuing a torrent of national guilt—“We have created this conflict that is now a test between Communism and freedom there.” The governor, normally controlled, was on a rare bender, and Gordon let him go.

Brainwashing had a specific connotation then: It was the term used to describe the ways in which the Communist state sought to control people’s minds; it conjured images of The Manchurian Candidate. The reference suggested that Romney was paranoid and naïve, and perhaps it also subtly reinforced the suspicion that his religion might be a cult. The Detroit News, for years his firmest supporter in the press, condemned him, and so did virtually everyone else—the chairman of the Republican party in Iowa, even his old friend Robert McNamara. In the Gallup poll, Nixon’s lead ballooned to 26 points. But Romney kept trying to explain his own alienation, kept doubling down. “I’m concerned about truth and credibility in government,” Romney began a fund-raising speech in Oregon seven days later. “I believe we face a credibility crisis in America today.” He blamed the Johnson administration, and then he went further: The crisis, he said, “involves a growing disbelief in some of our nation’s basic truths.”

Nobody in the Romney campaign, with the exception of George Romney himself, thought that beginning the fall of 1967 with a tour of the American ghetto was a very good idea. The national polls were getting worse, and in New Hampshire, site of the first primary, they were disastrous. The tour seemed strangely off-point; there was possibly not a single Republican vote to be won in Watts. But Romney himself seemed on a mission. “We must rouse ourselves from our comfort, pleasure, and preoccupations and listen to the voices from the ghetto,” he said in one speech. It was, after all, his campaign. He went.

The trip required advance men for seventeen cities. In Saint Louis, Bill Whitbeck followed close behind as Romney disappeared into a housing project where a woman “poured out this tale of woe—son killed, daughter raped. A searing experience.” In Washington, D.C., Romney met with Marion Barry; in Rochester, with Saul Alinsky, near portraits of Stokely Carmichael and Malcolm X. “I am more convinced than ever before that unless we reverse our course, build a new America, the old America will be destroyed,” he said.

Romney was talking into a vacuum. Republicans weren’t interested in the problems of the ghetto, and the ghetto wasn’t interested in Romney’s solutions. On his tour, as the historian Geoffrey Kabaservice writes inRule and Ruin, Romney was convinced that “independent citizens groups and local private-sector institutions could make a greater impact than federal programs in improving life in the slums.” What stayed with his staffers was the loneliness of Romney in the ghetto, the earnestness of the endeavor but also its delusion.

In Watts one day, Romney and Lenore were sitting in the back of a sedan, being chauffeured to the airport by a local driver, with Romney’s bodyguard riding shotgun. According to a story that circulated all through the campaign, Romney leaned forward: “Say, what is that word they keep saying to me? I don’t understand, it begins with an M…” The driver and the bodyguard racked their brains as Romney tried to pronounce it, working his western consonants around an inner-city accent. Then the driver straightened up and said, “Governor, I think what they’re saying is”—and here he let his voice get kind of ghetto—“mo’fucka.” And then, because Romney was legendarily a Mormon and these vulgarities may have been somewhat beyond him, the driver clarified: “Motherfucker, sir.” And Romney sank back into his seat, like a part of the car that had been mechanically retracted.

From within the Romney campaign—which is to say, from the unreconstructed core of country-club Republicanism—a kind of closeted leftward migration was under way. Moore had become so incensed with the Vietnam War that when he voted in 1972, it was for the Democratic peace candidate George McGovern. By the early seventies, De Vries had abandoned Republicans and was working for progressive Democratic candidates in North Carolina. And yet Romney, his alienation just as deep, did not follow them. Something kept him back.

The governor was not an intellectual. He found uncertainty uncomfortable. But on my second morning going through Romney’s papers, I found some notes he had made, on the stationery of the 1966 Midwestern Governors’ Conference. Beneath some doodles, from nowhere, Romney turned philosophical: “A great issue of our time: Does the urgent need to correct social injustice justify disobedience to law?” Something about this question seemed very important to him. “Need for Revelation,” Romney wrote, and he underlined that last word, Revelation.

He was having deep doubts. This was how liberals perceived the crises of the sixties. What followed was a searching internal inquiry, which Romney kept up over eight pages of furious scrawls, citing Martin Luther King Jr. in favor of radicalism in the name of justice, and Socrates and Abraham Lincoln against. Romney wrote down another quote: “Conscious of the fact that I cannot separate myself from the time in which I am living, I have decided to become a part of it.” The thought, improbably, is from Camus.

There are occasional moments in George Romney’s political career (the ghetto tour, for instance) in which you can feel his certainty dislodge, his attachment to the Republican Party loosen, his political commitments—to an American Establishment he would never fully inhabit, to an underclass culturally foreign to him, to a vision of the future swiftly becoming out of date—buckle under their contradictions. But if those notes from 1966 hold any insight, it is that in these moments of internal crisis, his faith was always decisive. His sprawling inquiry eventually turned to Christ, and then to some notes on Mormon teaching, recalling Joseph Smith’s admonishment to obey the law of the United States, even as it had discriminated against the Mormon Church. “God has given the answer,” Romney wrote. Mormons had made a compact with the United States: a deep loyalty in return for acceptance. “As Latter-Day-Saints,” Romney wrote, “let us obey the commandment of God to obey the law. Article of Faith.”

By November, Romney had had it. His campaign’s operating budget had been halved, and the line was that all of the remaining staffers were preparing memos explaining why the collapse was not their fault. Nixon flew into New Hampshire to give weekend speeches in front of crowds of 5,000; Romney trudged around milk plants. On a National Governors’ Conference cruise in the Virgin Islands, he visited Nelson Rockefeller’s cabin three times, pleading with the New York governor to run so that he could drop out. Rockefeller wouldn’t let him.

Romney kept going. His focus seemed on something other than winning. In November, he formally announced his candidacy in Detroit, giving a roaring speech about civil rights. Bill Whitbeck was sitting in the crowd, and the guy next to him said, “The governor wouldn’t give that speech in Missouri, would he?” Whitbeck said he would. Just after Christmas, a campaign pollster concluded that Nixon’s support in New Hampshire outnumbered Romney’s five to one. By the end of February, two weeks before the New Hampshire primary—before anyone had cast a vote for him—Romney dropped out. Mitt was in France at the time, on his church mission. “Your mother and I are not personally distressed,” George wrote his son. “As a matter of fact, we are relieved.”

Even before Romney’s breakdown on The Lou Gordon Program, he seemed bound to lose. And yet that word—brainwashing—betrays a great deal. What Romney had blurted out was that the destabilization of the sixties had reached those who believed most in the American Establishment. The military, the presidency, the centers of authority in American life could no longer be trusted. When Romney was asked by a reporter about American greatness, whether the country really compared with imperial Britain or ancient Greece, he replied, “It’s an open question.”

It is possible to think of the difference between George and Mitt Romney as a series of adaptive changes, in which the original moderate instincts have devolved so completely that Mitt’s response to a rising and angry conservatism resembles Nixon’s far more than his father’s. Perhaps Mitt noticed, following the 1968 campaign intently from Europe, that it was Nixon’s opportunism, his skill at exploiting fears of unsettling demographic change, that won. But it is also true that George Romney’s cherished institutions have lost their power, and the vision in which they would make a better society has collapsed. In Mitt’s politics, his father’s fervent progressivism has become instead an ideologically empty pragmatism that succumbs to whatever his audience wants to hear. What remains is the peculiar character of the current Republican nominee for president, an organization man without organizations.

By 1972, the era of the moderate Republican was already mostly over. One Friday, Whitbeck picked Romney up at the Detroit airport and drove the former governor home to Bloomfield Hills. Romney was, by this point, three and a half years into a job in which he had long ago become irrelevant but which he refused to leave, as Nixon’s secretary of Housing and Urban Development. There he had tried and failed to persuade the White House to pursue a policy of racial integration in housing, which is to say he tried and failed to implant some progressive habits in the heart of the modern Republican party, that odd amalgam of privilege and alienated rage. Romney was contemplative, and they talked about Washington for a while, until they were nearly home. “Bill,” Romney said then, quietly, “politics will break your heart.”

No comments:

Post a Comment