Dominican Preacher Bartolomé De Las Casas, 16th Century "Protector Of The Indians"

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2016/08/the-above-quotation-is-not-fabricated.htmlPersecution Of Heretics

The image below is found on page 345 of Samuel Moreland's "History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piedmont" published in London in 1658. It is one of a number of prints illustrating the massacre of the Waldenses in Provence in 1655. The woman being tortured to death here is Anna, daughter of Giovanni Charboniere of La Torre.

|

|

"Any Religion That Needs Fear To Thrive Is Bad Religion"

"Bad Religion: A Compendium"

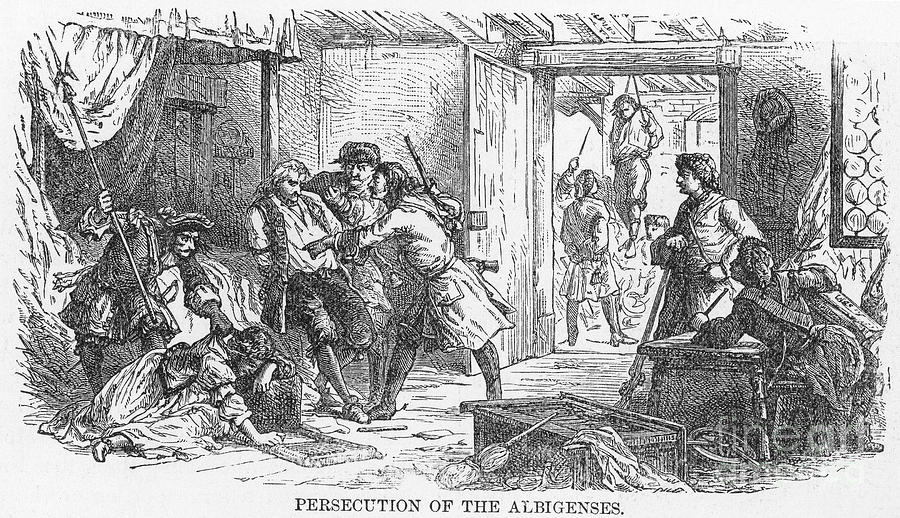

Albigensian Crusade

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Albigensian Crusade Part of the Crusades

Political map of Languedoc on the eve

of the Albigensian Crusade

Date 1209–1229 Location Languedoc, France Result Crusader victory

Belligerents

Kingdom of France

Crown of Aragon Commanders and leaders

Louis VIII of France

Peter II of Aragon †

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, in the south of France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crown and promptly took on a political flavour, resulting in not only a significant reduction in the number of practising Cathars, but also a realignment of the County of Toulouse, bringing it into the sphere of the French crown and diminishing the distinct regional culture and high level of influence of the Counts of Barcelona.

The medieval Christian sect of the Cathars, against whom the crusade was directed, originated from a reform movement within the Bogomil churches of Dalmatia and Bulgaria calling for a return to the Christian message of perfection, poverty and preaching. The reforms were a reaction against the often scandalous and dissolute lifestyles of the Catholic clergy in southern France. Their theology was basically dualist.[1] Several of their practices, especially their belief in the inherent evil of the physical world, which conflicted with the doctrines of the Incarnation of Christ and transubstantiation, brought them the ire of the Catholic establishment. They became known as the Albigensians, because there were many adherents in the city of Albi and the surrounding area in the 12th and 13th centuries.[2]

Between 1022 and 1163, they were condemned by eight local church councils, the last of which, held at Tours, declared that all Albigenses "should be imprisoned and their property confiscated," and by the Third Lateran Council of 1179.[3] Innocent III's diplomatic attempts to roll back Catharism[4] met with little success. After the murder of his legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in 1208, Innocent III declared a crusade against the Cathars. He offered the lands of the Cathar heretics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms. After initial successes, the French barons faced a general uprising in Languedoc which led to the intervention of the French royal army.

The Albigensian Crusade also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Dominican Order and the medieval inquisition.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229) was a 20-year military campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, in the south of France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crown and promptly took on a political flavour, resulting in not only a significant reduction in the number of practising Cathars, but also a realignment of the County of Toulouse, bringing it into the sphere of the French crown and diminishing the distinct regional culture and high level of influence of the Counts of Barcelona.

The medieval Christian sect of the Cathars, against whom the crusade was directed, originated from a reform movement within the Bogomil churches of Dalmatia and Bulgaria calling for a return to the Christian message of perfection, poverty and preaching. The reforms were a reaction against the often scandalous and dissolute lifestyles of the Catholic clergy in southern France. Their theology was basically dualist.[1] Several of their practices, especially their belief in the inherent evil of the physical world, which conflicted with the doctrines of the Incarnation of Christ and transubstantiation, brought them the ire of the Catholic establishment. They became known as the Albigensians, because there were many adherents in the city of Albi and the surrounding area in the 12th and 13th centuries.[2]

Between 1022 and 1163, they were condemned by eight local church councils, the last of which, held at Tours, declared that all Albigenses "should be imprisoned and their property confiscated," and by the Third Lateran Council of 1179.[3] Innocent III's diplomatic attempts to roll back Catharism[4] met with little success. After the murder of his legate, Pierre de Castelnau, in 1208, Innocent III declared a crusade against the Cathars. He offered the lands of the Cathar heretics to any French nobleman willing to take up arms. After initial successes, the French barons faced a general uprising in Languedoc which led to the intervention of the French royal army.

The Albigensian Crusade also had a role in the creation and institutionalization of both the Dominican Order and the medieval inquisition.

Contents

Origin[edit]

By the 12th century, organized groups of dissidents, such as the Waldensians and Cathars, were beginning to appear in the towns and cities of newly urbanized areas. In western Mediterranean France, one of the most urbanized areas of Europe at the time, the Cathars grew to represent a popular mass movement,[5] and the belief was spreading to other areas. Relatively few believers took the consolamentum to become full Cathars, but the movement attracted many followers and sympathisers.

The theology of the Cathars was dualistic, a belief in two equal and comparable transcendental principles; God, the force of good, and Satan, or the demiurge, the force of evil. They held that the physical world was evil and created by this demiurge, which they called Rex Mundi (Latin, "King of the World"). Rex Mundi encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful. The Cathar understanding of God was entirely disincarnate: they viewed God as a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the God of love, order and peace. Jesus was an angel with only a phantom body, and the accounts of him in the New Testament were to be understood allegorically. As the physical world and the human body were the creation of the evil principle, sexual abstinence (even in marriage) was encouraged.[1][6][7][8] Civil authority had no claim on a Cathar, since this was the rule of the physical world.

Deriving from earlier varieties of gnosticism, Cathar theology found its greatest success in the Languedoc. The Cathars were known as Albigensians because of their association with the city of Albi, and because the 1176 Church Council which declared the Cathar doctrine heretical was held near Albi.[9][10] In Languedoc, political control was divided among many local lords and town councils.[11] Before the crusade there was little fighting in the area and a fairly sophisticated polity. Western Mediterranean France itself was at that time divided between the Crown of Aragon and the county of Toulouse.

On becoming Pope in 1198, Innocent III resolved to deal with the Cathars and sent a delegation of friars to the province of Languedoc to assess the situation. The Cathars of Languedoc were seen as not showing proper respect for the authority of the French king or the local Catholic Church, and their leaders were being protected by powerful nobles,[12] who had clear interest in independence from the king.

One of the most powerful, Count Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse openly supported the Cathars and their independence movement. He refused to assist the delegation. He was excommunicated in May 1207 and an interdict was placed on his lands. The senior papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, seen as responsible for these actions, was killed and his death was attributed to supporters of the count.[3] This brought down more penalties on Count Raymond, but he soon agreed to reconcile with the Church and the excommunication was lifted. At the Council of Avignon (1209) Raymond was again excommunicated for not fulfilling the conditions of ecclesiastical reconciliation.[3] King Philip II of France decided to act against those nobles who permitted Catharism within their lands and undermined secular authority. Though the actual crusade lasted only two months, the internal conflict between the north and the south of France continued for some twenty years.

By the 12th century, organized groups of dissidents, such as the Waldensians and Cathars, were beginning to appear in the towns and cities of newly urbanized areas. In western Mediterranean France, one of the most urbanized areas of Europe at the time, the Cathars grew to represent a popular mass movement,[5] and the belief was spreading to other areas. Relatively few believers took the consolamentum to become full Cathars, but the movement attracted many followers and sympathisers.

The theology of the Cathars was dualistic, a belief in two equal and comparable transcendental principles; God, the force of good, and Satan, or the demiurge, the force of evil. They held that the physical world was evil and created by this demiurge, which they called Rex Mundi (Latin, "King of the World"). Rex Mundi encompassed all that was corporeal, chaotic and powerful. The Cathar understanding of God was entirely disincarnate: they viewed God as a being or principle of pure spirit and completely unsullied by the taint of matter. He was the God of love, order and peace. Jesus was an angel with only a phantom body, and the accounts of him in the New Testament were to be understood allegorically. As the physical world and the human body were the creation of the evil principle, sexual abstinence (even in marriage) was encouraged.[1][6][7][8] Civil authority had no claim on a Cathar, since this was the rule of the physical world.

Deriving from earlier varieties of gnosticism, Cathar theology found its greatest success in the Languedoc. The Cathars were known as Albigensians because of their association with the city of Albi, and because the 1176 Church Council which declared the Cathar doctrine heretical was held near Albi.[9][10] In Languedoc, political control was divided among many local lords and town councils.[11] Before the crusade there was little fighting in the area and a fairly sophisticated polity. Western Mediterranean France itself was at that time divided between the Crown of Aragon and the county of Toulouse.

On becoming Pope in 1198, Innocent III resolved to deal with the Cathars and sent a delegation of friars to the province of Languedoc to assess the situation. The Cathars of Languedoc were seen as not showing proper respect for the authority of the French king or the local Catholic Church, and their leaders were being protected by powerful nobles,[12] who had clear interest in independence from the king.

One of the most powerful, Count Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse openly supported the Cathars and their independence movement. He refused to assist the delegation. He was excommunicated in May 1207 and an interdict was placed on his lands. The senior papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, seen as responsible for these actions, was killed and his death was attributed to supporters of the count.[3] This brought down more penalties on Count Raymond, but he soon agreed to reconcile with the Church and the excommunication was lifted. At the Council of Avignon (1209) Raymond was again excommunicated for not fulfilling the conditions of ecclesiastical reconciliation.[3] King Philip II of France decided to act against those nobles who permitted Catharism within their lands and undermined secular authority. Though the actual crusade lasted only two months, the internal conflict between the north and the south of France continued for some twenty years.

Military campaigns[edit]

The military campaigns of the crusade may be divided into several periods. The first, from 1209 to 1215, contained a series of great successes for the crusaders in Languedoc, with episodes of extreme violence such as the slaughter of the population of Béziers. The forces assembled mainly from the Ile de France and the north of France, led bySimon de Montfort, faced the nobility of Toulouse, led by Count Raymond VI of Toulouse and the Trencavel family that, as allies and vassals of the Crown of Aragon, sought help from King Peter II of Aragon. Peter II was killed in the course of the Battle of Muret in 1213.[13]

The captured lands were largely lost between 1215 and 1225 in a series of revolts and military reverses. The death of Simon de Montfort at Toulouse after the return of CountRaymond VII of Toulouse and the consolidation of Albigensian resistance supported by the forces of the Count of Foix and the Crown of Aragon, resulted in the military intervention of Louis VIII of France from 1226 with the support of Pope Honorius III.

The situation turned again following the intervention of the French king, Louis VIII, in 1226. He died in November of that year, but the struggle continued under King Louis IX, and the area was reconquered by 1229; the leading nobles made peace, culminating in the Treaty of Meaux-Paris in 1229, by the terms of which it was agreed that the County of Toulouse would be integrated into the French crown. After 1233, theInquisition was central to crushing what remained of Catharism. Resistance and occasional revolts continued, but the days of Catharism were numbered. Military action ceased in 1255.

The military campaigns of the crusade may be divided into several periods. The first, from 1209 to 1215, contained a series of great successes for the crusaders in Languedoc, with episodes of extreme violence such as the slaughter of the population of Béziers. The forces assembled mainly from the Ile de France and the north of France, led bySimon de Montfort, faced the nobility of Toulouse, led by Count Raymond VI of Toulouse and the Trencavel family that, as allies and vassals of the Crown of Aragon, sought help from King Peter II of Aragon. Peter II was killed in the course of the Battle of Muret in 1213.[13]

The captured lands were largely lost between 1215 and 1225 in a series of revolts and military reverses. The death of Simon de Montfort at Toulouse after the return of CountRaymond VII of Toulouse and the consolidation of Albigensian resistance supported by the forces of the Count of Foix and the Crown of Aragon, resulted in the military intervention of Louis VIII of France from 1226 with the support of Pope Honorius III.

The situation turned again following the intervention of the French king, Louis VIII, in 1226. He died in November of that year, but the struggle continued under King Louis IX, and the area was reconquered by 1229; the leading nobles made peace, culminating in the Treaty of Meaux-Paris in 1229, by the terms of which it was agreed that the County of Toulouse would be integrated into the French crown. After 1233, theInquisition was central to crushing what remained of Catharism. Resistance and occasional revolts continued, but the days of Catharism were numbered. Military action ceased in 1255.

Initial success 1209 to 1215[edit]

By mid-1209, around 10,000 crusaders had gathered in Lyon before marching south.[14] In June, Raymond of Toulouse, recognizing the disaster at hand, finally promised to act against the Cathars, and his excommunication was lifted.[15] The crusaders turned towards Montpellier and the lands of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel, aiming for the Cathar communities around Albi and Carcassonne. Like Raymond of Toulouse, Raymond-Roger sought an accommodation with the crusaders, but he was refused a meeting and raced back to Carcassonne to prepare his defences.[16]

By mid-1209, around 10,000 crusaders had gathered in Lyon before marching south.[14] In June, Raymond of Toulouse, recognizing the disaster at hand, finally promised to act against the Cathars, and his excommunication was lifted.[15] The crusaders turned towards Montpellier and the lands of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel, aiming for the Cathar communities around Albi and Carcassonne. Like Raymond of Toulouse, Raymond-Roger sought an accommodation with the crusaders, but he was refused a meeting and raced back to Carcassonne to prepare his defences.[16]

Massacre at Béziers[edit]

The crusaders captured the small village of Servian and then headed for Béziers, arriving on 21 July 1209. Under the command of the papal legate, Arnaud-Amaury,[17] they started to besiege the city, calling on the Catholics within to come out, and demanding that the Cathars surrender.[18] Both groups refused. The city fell the following day when an abortive sortie was pursued back through the open gates.[19] The entire population was slaughtered and the city burned to the ground. Contemporary sources give estimates of the number of dead ranging between 15,000 and 20,000. The latter figure appears in Arnaud-Amaury's report to the pope.[20] The news of the disaster quickly spread and afterwards many settlements surrendered without a fight.

The crusaders captured the small village of Servian and then headed for Béziers, arriving on 21 July 1209. Under the command of the papal legate, Arnaud-Amaury,[17] they started to besiege the city, calling on the Catholics within to come out, and demanding that the Cathars surrender.[18] Both groups refused. The city fell the following day when an abortive sortie was pursued back through the open gates.[19] The entire population was slaughtered and the city burned to the ground. Contemporary sources give estimates of the number of dead ranging between 15,000 and 20,000. The latter figure appears in Arnaud-Amaury's report to the pope.[20] The news of the disaster quickly spread and afterwards many settlements surrendered without a fight.

Fall of Carcassonne[edit]

The next major target was Carcassonne. The city was well fortified, but vulnerable, and overflowing with refugees.[21] The crusaders arrived on 1 August 1209. The siege did not last long.[22] By 7 August they had cut the city's water supply. Raymond-Roger sought negotiations but was taken prisoner while under truce, and Carcasonne surrendered on 15 August.[23] The people were not killed, but were forced to leave the town — naked according to Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay, "In their shifts and breeches" according to another source[who?]. Simon de Montfort was then appointed leader of the crusader army,[24] and was granted control of the area encompassing Carcassonne, Albi, and Béziers. After the fall of Carcassonne, other towns surrendered without a fight: Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Fanjeaux, Limoux, Lombersand Montréal all fell quickly during the autumn.[25] However, some of the towns that had surrendered later revolted.

The next major target was Carcassonne. The city was well fortified, but vulnerable, and overflowing with refugees.[21] The crusaders arrived on 1 August 1209. The siege did not last long.[22] By 7 August they had cut the city's water supply. Raymond-Roger sought negotiations but was taken prisoner while under truce, and Carcasonne surrendered on 15 August.[23] The people were not killed, but were forced to leave the town — naked according to Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay, "In their shifts and breeches" according to another source[who?]. Simon de Montfort was then appointed leader of the crusader army,[24] and was granted control of the area encompassing Carcassonne, Albi, and Béziers. After the fall of Carcassonne, other towns surrendered without a fight: Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Fanjeaux, Limoux, Lombersand Montréal all fell quickly during the autumn.[25] However, some of the towns that had surrendered later revolted.

Lastours and the castle of Cabaret[edit]

The next battle centred around Lastours and the adjacent castle of Cabaret. Attacked in December 1209, Pierre Roger de Cabaret repulsed the assault.[26]Fighting largely halted over the winter, but fresh crusaders arrived.[27] In March 1210, Bram was captured after a short siege.[28] In June the well-fortified city ofMinerve was besieged.[29] It withstood a heavy bombardment, but in late June the main well was destroyed and on July 22, the city surrendered.[30] The Cathars were given the opportunity to convert to Catholicism. Most did. The 140 who refused were burned at the stake.[31] In August the crusade proceeded to the stronghold of Termes.[32] Despite sallies from Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, the siege was solid, and in December the town fell.[33] It was the last action of the year.

By the time operations resumed in 1211, the actions of Arnaud-Amaury and Simon de Montfort had alienated several important lords, including Raymond de Toulouse,[34] who had been excommunicated again. The crusaders returned in force to Lastours in March and Pierre-Roger de Cabaret soon agreed to surrender. In May the castle of Aimery de Montréal was retaken; he and his senior knights were hanged, and several hundred Cathars were burned.[35] Cassès[36] and Montferrand[37] both fell easily in early June and the crusaders headed for Toulouse.[38] The town was besieged, but for once the attackers were short of supplies and men, and Simon de Montfort withdrew before the end of the month.[39] Emboldened, Raymond de Toulouse led a force to attack Montfort at Castelnaudary in September.[40] Montfort broke free from the siege[41] but Castelnaudary fell and Raymond's forces went on to liberate over thirty towns[42] before the counter-attack ground to a halt at Lastours, in the autumn. The following year much of the province of Toulouse was captured by Catholic forces.[43]

The next battle centred around Lastours and the adjacent castle of Cabaret. Attacked in December 1209, Pierre Roger de Cabaret repulsed the assault.[26]Fighting largely halted over the winter, but fresh crusaders arrived.[27] In March 1210, Bram was captured after a short siege.[28] In June the well-fortified city ofMinerve was besieged.[29] It withstood a heavy bombardment, but in late June the main well was destroyed and on July 22, the city surrendered.[30] The Cathars were given the opportunity to convert to Catholicism. Most did. The 140 who refused were burned at the stake.[31] In August the crusade proceeded to the stronghold of Termes.[32] Despite sallies from Pierre-Roger de Cabaret, the siege was solid, and in December the town fell.[33] It was the last action of the year.

By the time operations resumed in 1211, the actions of Arnaud-Amaury and Simon de Montfort had alienated several important lords, including Raymond de Toulouse,[34] who had been excommunicated again. The crusaders returned in force to Lastours in March and Pierre-Roger de Cabaret soon agreed to surrender. In May the castle of Aimery de Montréal was retaken; he and his senior knights were hanged, and several hundred Cathars were burned.[35] Cassès[36] and Montferrand[37] both fell easily in early June and the crusaders headed for Toulouse.[38] The town was besieged, but for once the attackers were short of supplies and men, and Simon de Montfort withdrew before the end of the month.[39] Emboldened, Raymond de Toulouse led a force to attack Montfort at Castelnaudary in September.[40] Montfort broke free from the siege[41] but Castelnaudary fell and Raymond's forces went on to liberate over thirty towns[42] before the counter-attack ground to a halt at Lastours, in the autumn. The following year much of the province of Toulouse was captured by Catholic forces.[43]

Toulouse[edit]

In 1213, forces led by King Peter II of Aragon, came to the aid of Toulouse.[44] The force besieged Muret,[45] but in September the Battle of Muret led to the death of King Peter,[46] and his army fled (this battle also marks the end of Catalan influence north of the Pyrenees and the definitive separation of the two geographical areas, Languedoc and Catalonia).

It was a serious blow for the resistance, and in 1214 the situation became worse: Raymond was forced to flee to England,[47] and his lands were given by the pope to the victorious Philip II,[citation needed] a stratagem which finally succeeded in interesting the king in the conflict. In November the always active Simon de Montfort entered Périgord[48] and easily captured the castles of Domme[49] and Montfort;[50] he also occupiedCastlenaud and destroyed the fortifications of Beynac.[51] In 1215, Castelnaud was recaptured by Montfort,[52] and the crusaders entered Toulouse. Toulouse was gifted to Montfort.[53] In April 1216 he ceded his lands to Philip.

In 1213, forces led by King Peter II of Aragon, came to the aid of Toulouse.[44] The force besieged Muret,[45] but in September the Battle of Muret led to the death of King Peter,[46] and his army fled (this battle also marks the end of Catalan influence north of the Pyrenees and the definitive separation of the two geographical areas, Languedoc and Catalonia).

It was a serious blow for the resistance, and in 1214 the situation became worse: Raymond was forced to flee to England,[47] and his lands were given by the pope to the victorious Philip II,[citation needed] a stratagem which finally succeeded in interesting the king in the conflict. In November the always active Simon de Montfort entered Périgord[48] and easily captured the castles of Domme[49] and Montfort;[50] he also occupiedCastlenaud and destroyed the fortifications of Beynac.[51] In 1215, Castelnaud was recaptured by Montfort,[52] and the crusaders entered Toulouse. Toulouse was gifted to Montfort.[53] In April 1216 he ceded his lands to Philip.

Revolts and reverses 1216 to 1225[edit]

However, Raymond, together with his son, returned to the region in April 1216 and soon raised a substantial force from disaffected towns. Beaucaire was besieged in May and fell after three months; the efforts of Montfort to relieve the town were repulsed. Montfort then had to put down an uprising in Toulouse before heading west to capture Bigorre, but he was repulsed at Lourdes in December 1216. In September 1217, Raymond retook Toulouse while Montfort was occupied in the Foix region. Montfort hurried back, but his forces were insufficient to retake the town before campaigning halted. Montfort renewed the siege in the spring of 1218. While attempting to fend off a sally by the defenders, Montfort was struck and killed by a stone hurled from defensive siege equipment.[54] Popular accounts state that the city's artillery was operated by the women and girls of Toulouse.[54]

Innocent III died in July 1216 and with Montfort now dead, the crusade was left in temporary disarray. The command passed to the more cautious Philippe II, who was more concerned with Toulouse than heresy. The crusaders had taken Belcaire and besieged Marmande in late 1218 under Amaury de Montfort, son of the late Simon. While Marmande fell on June 3, 1219, attempts to retake Toulouse failed, and a number of Montfort holds also fell. In 1220, Castelnaudary was retaken from Montfort. He again besieged the town in July 1220, but it withstood an eight-month assault. In 1221, the success of Raymond and his son continued: Montréal and Fanjeaux were retaken and many Catholics were forced to flee. In 1222, Raymond died and was succeeded by his son, also named Raymond. In 1223, Philip II died and was succeeded by Louis VIII. In 1224, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carcassonne. The son of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel returned from exile to reclaim the area. Montfort offered his claim to the lands of Languedoc to Louis VIII, who accepted.

However, Raymond, together with his son, returned to the region in April 1216 and soon raised a substantial force from disaffected towns. Beaucaire was besieged in May and fell after three months; the efforts of Montfort to relieve the town were repulsed. Montfort then had to put down an uprising in Toulouse before heading west to capture Bigorre, but he was repulsed at Lourdes in December 1216. In September 1217, Raymond retook Toulouse while Montfort was occupied in the Foix region. Montfort hurried back, but his forces were insufficient to retake the town before campaigning halted. Montfort renewed the siege in the spring of 1218. While attempting to fend off a sally by the defenders, Montfort was struck and killed by a stone hurled from defensive siege equipment.[54] Popular accounts state that the city's artillery was operated by the women and girls of Toulouse.[54]

Innocent III died in July 1216 and with Montfort now dead, the crusade was left in temporary disarray. The command passed to the more cautious Philippe II, who was more concerned with Toulouse than heresy. The crusaders had taken Belcaire and besieged Marmande in late 1218 under Amaury de Montfort, son of the late Simon. While Marmande fell on June 3, 1219, attempts to retake Toulouse failed, and a number of Montfort holds also fell. In 1220, Castelnaudary was retaken from Montfort. He again besieged the town in July 1220, but it withstood an eight-month assault. In 1221, the success of Raymond and his son continued: Montréal and Fanjeaux were retaken and many Catholics were forced to flee. In 1222, Raymond died and was succeeded by his son, also named Raymond. In 1223, Philip II died and was succeeded by Louis VIII. In 1224, Amaury de Montfort abandoned Carcassonne. The son of Raymond-Roger de Trencavel returned from exile to reclaim the area. Montfort offered his claim to the lands of Languedoc to Louis VIII, who accepted.

French royal intervention[edit]

In November 1225, at a Council of Bourges, Raymond, like his father, was excommunicated. The council gathered a thousand churchmen to authorize a tax on their annual incomes, the "Albigensian tenth", to support the crusade, though permanent reforms intended to fund the papacy in perpetuity foundered.[55] Louis VIII headed the new crusade into the area in June 1226. Fortified towns and castles surrendered without resistance. However, Avignon, nominally under the rule of the German emperor, did resist, and it took a three-month siege to force its surrender that September. Louis VIII died in November and was succeeded by the child king Louis IX. But Queen-regent Blanche of Castile allowed the crusade to continue under Humbert de Beaujeu. Labécède fell in 1227 and Vareilles in 1228. While besieging Toulouse, the crusaders systematically laid waste to the surrounding landscape: uprooting vineyards, burning fields and farms, slaughtering livestock.[56] Raymond did not have the manpower to intervene. Eventually Queen Blanche offered Raymond a treaty recognizing him as ruler of Toulouse in exchange for his fighting the Cathars, returning all church property, turning over his castles and destroying the defenses of Toulouse. Moreover, Raymond had to marry his daughter Jeanne to Louis' brother Alphonse, with the couple and their heirs obtaining Toulouse after Raymond's death, and the inheritance reverting to the king in the event that they did not have issue, as eventually proved to be the case. Raymond agreed and signed the Treaty of Paris at Meaux on April 12, 1229. He was then seized, whipped and briefly imprisoned.

In November 1225, at a Council of Bourges, Raymond, like his father, was excommunicated. The council gathered a thousand churchmen to authorize a tax on their annual incomes, the "Albigensian tenth", to support the crusade, though permanent reforms intended to fund the papacy in perpetuity foundered.[55] Louis VIII headed the new crusade into the area in June 1226. Fortified towns and castles surrendered without resistance. However, Avignon, nominally under the rule of the German emperor, did resist, and it took a three-month siege to force its surrender that September. Louis VIII died in November and was succeeded by the child king Louis IX. But Queen-regent Blanche of Castile allowed the crusade to continue under Humbert de Beaujeu. Labécède fell in 1227 and Vareilles in 1228. While besieging Toulouse, the crusaders systematically laid waste to the surrounding landscape: uprooting vineyards, burning fields and farms, slaughtering livestock.[56] Raymond did not have the manpower to intervene. Eventually Queen Blanche offered Raymond a treaty recognizing him as ruler of Toulouse in exchange for his fighting the Cathars, returning all church property, turning over his castles and destroying the defenses of Toulouse. Moreover, Raymond had to marry his daughter Jeanne to Louis' brother Alphonse, with the couple and their heirs obtaining Toulouse after Raymond's death, and the inheritance reverting to the king in the event that they did not have issue, as eventually proved to be the case. Raymond agreed and signed the Treaty of Paris at Meaux on April 12, 1229. He was then seized, whipped and briefly imprisoned.

After 1229[edit]

The Inquisition was established in 1234 to uproot the remaining Cathars.[57] Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it succeeded in crushing Catharism as a popular movement and driving its remaining adherents underground.[57] Punishments for Cathars who refused to recant ranged from cross wearing and pilgrimage to imprisonment and burning.

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged by the troops of the seneschal of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne.[58] On 16 March 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, where over 200 Cathar Perfects were burnt in an enormous pyre at the prat dels cremats ("field of the burned") near the foot of the castle.[58]

The Inquisition was established in 1234 to uproot the remaining Cathars.[57] Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it succeeded in crushing Catharism as a popular movement and driving its remaining adherents underground.[57] Punishments for Cathars who refused to recant ranged from cross wearing and pilgrimage to imprisonment and burning.

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged by the troops of the seneschal of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne.[58] On 16 March 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, where over 200 Cathar Perfects were burnt in an enormous pyre at the prat dels cremats ("field of the burned") near the foot of the castle.[58]

Genocide[edit]

Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide, referred to the Albigensian Crusade as "one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[59]

Mark Gregory Pegg writes that "The Albigensian Crusade ushered genocide into the West by linking divine salvation to mass murder, by making slaughter as loving an act as His sacrifice on the cross".[60] Robert E. Lerner argues that Pegg's classification of the Albigensian Crusade as a genocide is inappropriate, on the grounds that it "was proclaimed against unbelievers... not against a 'genus' or people; those who joined the crusade had no intention of annihilating the population of southern France... If Pegg wishes to connect the Albigensian Crusade to modern ethnic slaughter, well—words fail me (as they do him)."[61] Laurence Marvin is not as dismissive as Lerner regarding Pegg's contention that the Albigensian Crusade was a genocide; he does however take issue with Pegg's argument that the Albigensian Crusade formed an important historical precedent for later genocides including the Holocaust.[62]

Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Solveig Björnson describe the Albigensian Crusade as "the first ideological genocide".[63] Kurt Jonassohn and Frank Chalk (who together founded the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies) include a detailed case study of the Albigensian Crusade in their genocide studies textbookThe History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies, authored by Joseph R. Strayer and Malise Ruthven.[64]

Colin Tatz likewise classifies the Albigensian Crusade as a genocide.[65]

***

Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide, referred to the Albigensian Crusade as "one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[59]

Mark Gregory Pegg writes that "The Albigensian Crusade ushered genocide into the West by linking divine salvation to mass murder, by making slaughter as loving an act as His sacrifice on the cross".[60] Robert E. Lerner argues that Pegg's classification of the Albigensian Crusade as a genocide is inappropriate, on the grounds that it "was proclaimed against unbelievers... not against a 'genus' or people; those who joined the crusade had no intention of annihilating the population of southern France... If Pegg wishes to connect the Albigensian Crusade to modern ethnic slaughter, well—words fail me (as they do him)."[61] Laurence Marvin is not as dismissive as Lerner regarding Pegg's contention that the Albigensian Crusade was a genocide; he does however take issue with Pegg's argument that the Albigensian Crusade formed an important historical precedent for later genocides including the Holocaust.[62]

Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Solveig Björnson describe the Albigensian Crusade as "the first ideological genocide".[63] Kurt Jonassohn and Frank Chalk (who together founded the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies) include a detailed case study of the Albigensian Crusade in their genocide studies textbookThe History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies, authored by Joseph R. Strayer and Malise Ruthven.[64]

Colin Tatz likewise classifies the Albigensian Crusade as a genocide.[65]

***

Alan: As prelude to the following article on "killing infidels," I will mention my long-standing astonishment that the Book of Deuteronomy not only permits, but obliges entire communities to stone children to death for the crime of "being children." I know of no command in any other religion's sacred scripture that is so zealous in slaughtering its own children.... "for being children."

The Most Bloodthirsty Obligation In Any Of The World's Sacred Scriptures Is Found In The Bible

Yes, the Bible Does Say to Kill Infidels

January 22, 2015 by 1680 Comments

Conservative Christians love to rail against the many verses in the Quran that command Muslims to kill non-Muslims, but they also ignore the verses in the Bible commanding the same thing and things that are every bit as barbaric. Tim Wildmon of the American Family Association flat out denies that such verses exist at all:

“The Quran has explicit admonitions or instructions for followers of Allah to do violence and harm against the infidel,” Wildmon fumed. “There’s nothing like that in the Bible, that tells the Christian to go out and decapitate the infidel.”

The video:

How about Deuteronomy 17:

Deuteronomy 17If there be found among you, within any of thy gates which the LORD thy God giveth thee, man or woman, that hath wrought wickedness in the sight of the LORD thy God, in transgressing his covenant; 17:3 And hath gone and served other gods, and worshipped them, either the sun, or moon, or any of the host of heaven, which I have not commanded; 17:4 And it be told thee, and thou hast heard of it, and enquired diligently, and, behold, it be true, and the thing certain, that such abomination is wrought in Israel; 17:5 Then shalt thou bring forth that man or that woman, which have committed that wicked thing, unto thy gates, even that man or that woman, and shalt stone them with stones, till they die.

Or Deuteronomy 13:

6 If your very own brother, or your son or daughter, or the wife you love, or your closest friend secretly entices you, saying, “Let us go and worship other gods” (gods that neither you nor your ancestors have known, 7 gods of the peoples around you, whether near or far, from one end of the land to the other), 8 do not yield to them or listen to them. Show them no pity. Do not spare them or shield them. 9 You must certainly put them to death. Your hand must be the first in putting them to death, and then the hands of all the people. 10 Stone them to death, because they tried to turn you away from the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. 11 Then all Israel will hear and be afraid, and no one among you will do such an evil thing again.12 If you hear it said about one of the towns the Lord your God is giving you to live in 13 that troublemakers have arisen among you and have led the people of their town astray, saying, “Let us go and worship other gods” (gods you have not known), 14 then you must inquire, probe and investigate it thoroughly. And if it is true and it has been proved that this detestable thing has been done among you, 15 you must certainly put to the sword all who live in that town. You must destroy it completely, both its people and its livestock. 16 You are to gather all the plunder of the town into the middle of the public square and completely burn the town and all its plunder as a whole burnt offering to the Lord your God. That town is to remain a ruin forever, never to be rebuilt.

No comments:

Post a Comment