Walter Benjamin on Information vs. Wisdom and How the Novel and the News Killed Storytelling

by Maria Popova

“Counsel woven into the fabric of real life is wisdom. The art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out.”

I think often, and with billowing concern, about the role of storytellers in helping uscultivate wisdom in the age of information — a task increasingly challenging and increasingly important as we find ourselves bombarded with bits of disjoined information, devoid of the sensemaking context that only deft storytelling can impart. Listicles commandeer these bits into alleged order, furthering our collective delusion of mistaking information for truth and meaning; there is a reason, after all, why we call such disjointed bits of information “trivia” — the true material of wisdom is meaning, and the meaningful is the opposite of the trivial. Although the list may bethe origin of culture, truth and meaning are culture’s end goal. A listicle can never order information into truth, much less imbue it with meaning. Only the storyteller can transmute information — be it in the form of “objective” fact or “subjective” experience — into wisdom.

I think often, and with billowing concern, about the role of storytellers in helping uscultivate wisdom in the age of information — a task increasingly challenging and increasingly important as we find ourselves bombarded with bits of disjoined information, devoid of the sensemaking context that only deft storytelling can impart. Listicles commandeer these bits into alleged order, furthering our collective delusion of mistaking information for truth and meaning; there is a reason, after all, why we call such disjointed bits of information “trivia” — the true material of wisdom is meaning, and the meaningful is the opposite of the trivial. Although the list may bethe origin of culture, truth and meaning are culture’s end goal. A listicle can never order information into truth, much less imbue it with meaning. Only the storyteller can transmute information — be it in the form of “objective” fact or “subjective” experience — into wisdom.

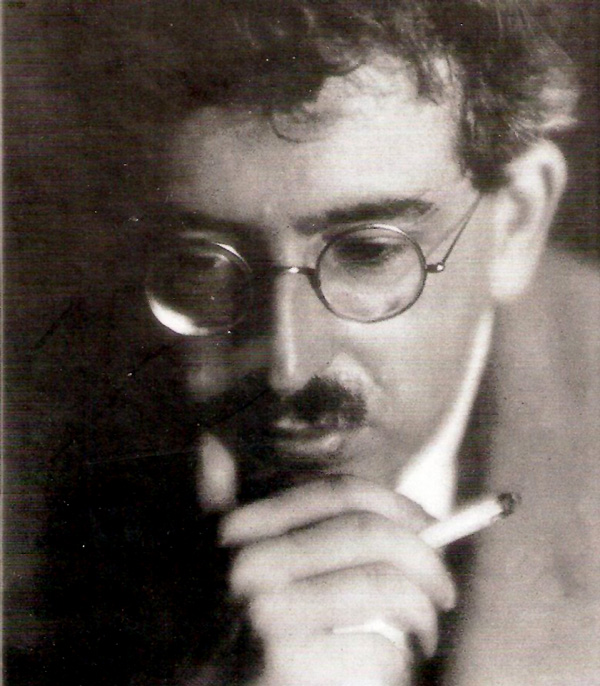

A century before the age of the listicle, German philosopher, cultural theorist, literary critic, and unflinching idealist Walter Benjamin (July 15, 1892–September 26, 1940) explored this dance between information and wisdom with great insight and prescience in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (public library) — a compendium of Benjamin’s ideas on language, literature, and life, originally published in 1968 and edited by the brilliant Hannah Arendt. In the introduction, Arendt envelops Benjamin’s genius in her own to describe him as “an alchemist practicing the obscure art of transmuting the futile elements of the real into the shining, enduring gold of truth.”

The most dazzling such transmutation takes place in an essay titled “The Storyteller,” in which Benjamin uses the work of 19th-century Russian writer Nikolai Leskov as a springboard for a higher-order meditation on the role of storytelling in society, the dangers of its decline, and how it shapes our relationship to truth, both public and private. The picture Benjamin paints begins in darkness but reaches toward the light.

He writes:

Familiar though his name may be to us, the storyteller in his living immediacy is by no means a present force. He has already become something remote from us and something that is getting even more distant… Viewed from a certain distance, the great, simple outlines which define the storyteller stand out in him, or rather, they become visible in him, just as in a rock a human head or an animal’s body may appear to an observer at the proper distance and angle of vision. This distance and this angle of vision are prescribed for us by an experience which we may have almost every day. It teaches us that the art of storytelling is coming to an end. Less and less frequently do we encounter people with the ability to tell a tale properly. More and more often there is embarrassment all around when the wish to hear a story is expressed. It is as if something that seemed inalienable to us, the securest among our possessions, were taken from us: the ability to exchange experiences.One reason for this phenomenon is obvious: experience has fallen in value. And it looks as if it is continuing to fall into bottomlessness.

A century ago, Benjamin directs his lament about the commodification of experience at the newspaper — a medium enjoying its commercial heyday, not without timelessly timely criticism — but it applies all the more piercingly to the whole buzzfeedery of today’s online news and entertainment industry:

Every glance at a newspaper demonstrates that it has reached a new low, that our picture, not only of the external world but of the moral world as well, overnight has undergone changes which were never thought possible.[…]Never has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power. A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.

Long before contemporary psychologists came to advocate for the enormous importance of practical wisdom in human life, Benjamin argues for the value — the practical use, even — of great storytelling in our lives:

An orientation toward practical interests is characteristic of many born storytellers… This points to the nature of every real story. It contains, openly or covertly, something useful. The usefulness may, in one case, consist in a moral; in another, in some practical advice; in a third, in a proverb or maxim. In every case the storyteller is a man who has counsel for his readers. But if today “having counsel” is beginning to have an old-fashioned ring, this is because the communicability of experience is decreasing. In consequence we have no counsel either for ourselves or for others. After all, counsel is less an answer to a question than a proposal concerning the continuation of a story which is just unfolding. To seek this counsel one would first have to be able to tell the story.

One can hear the echo of Rilke’s passionate exhortation to “live the questions” — a celebration of the uncertainty necessary for the telling of truth — in Benjamin’s case for the sensemaking power of story. To this he adds a point both piercing and prescient, which instantly strips of validity our essential illusion that the most pressing issues of our time are singular and unprecedented in human history:

Counsel woven into the fabric of real life is wisdom. The art of storytelling is reaching its end because the epic side of truth, wisdom, is dying out. This, however, is a process that has been going on for a long time. And nothing would be more fatuous than to want to see in it merely a “symptom of decay,” let alone a “modern” symptom. It is, rather, only a concomitant symptom of the secular productive forces of history, a concomitant that has quite gradually removed narrative from the realm of living speech and at the same time is making it possible to see a new beauty in what is vanishing.

And then he veers into an unexpected direction, at first striking and then strikingly brilliant in its intellectual elegance, as he identifies the true executioner of storytelling:

The earliest symptom of a process whose end is the decline of storytelling is the rise of the novel at the beginning of modern times. What distinguishes the novel from the story … is its essential dependence on the book. The dissemination of the novel became possible only with the invention of printing. What can be handed on orally, the wealth of the epic, is of a different kind from what constitutes the stock in trade of the novel. What differentiates the novel from all other forms of prose literature — the fairy tale, the legend, even the novella — is that it neither comes from oral tradition nor goes into it. This distinguishes it from storytelling in particular. The storyteller takes what he tells from experience — his own or that reported by others. And he in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to his tale. The novelist has isolated himself. The birthplace of the novel is the solitary individual, who is no longer able to express himself by giving examples of his most important concerns, is himself uncounseled, and cannot counsel others. To write a novel means to carry the incommensurable to extremes in the representation of human life. In the midst of life’s fullness, and through the representation of this fullness, the novel gives evidence of the profound perplexity of the living.

In a remark that calls to mind Virginia Woolf’s scathing view of all things middlebrow, Benjamin adds:

Hardly any other forms of human communication have taken shape more slowly, been lost more slowly. It took the novel, whose beginnings go back to antiquity, hundreds of years before it encountered in the evolving middle class those elements which were favorable to its flowering. With the appearance of these elements, storytelling began quite slowly to recede into the archaic; in many ways, it is true, it took hold of the new material, but it was not really determined by it. On the other hand, we recognize that with the full control of the middle class, which has the press as one of its most important instruments in fully developed capitalism, there emerges a form of communication which, no matter how far back its origin may lie, never before influenced the epic form in a decisive way. But now it does exert such an influence. And it turns out that it confronts storytelling as no less of a stranger than did the novel, but in a more menacing way, and that it also brings about a crisis in the novel.

And then, the essential point:

This new form of communication is information.

Paul Otlet's early-20th-century proto-internet, the Mundaneum, from 'Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age.' Click image for more.

The death of storytelling, Benjamin argues, is both the result and a further cause of this gaping rift between wisdom and information — a concern even more valid and worrisome today, in our story-yelling era driven by the illusion that the latest and the loudest are the most significant and most deserving of our attention. Benjamin writes:

It is no longer intelligence coming from afar, but the information which supplies a handle for what is nearest that gets the readiest hearing. The intelligence that came from afar — whether the spatial kind from foreign countries or the temporal kind of tradition — possessed an authority which gave it validity, even when it was not subject to verification. Information, however, lays claim to prompt verifiability. The prime requirement is that it appear “understandable in itself.” Often it is no more exact than the intelligence of earlier centuries was. But while the latter was inclined to borrow from the miraculous, it is indispensable for information to sound plausible. Because of this it proves incompatible with the spirit of storytelling.

Chiefly responsible for the decline of storytelling, Benjamin argues, is the rise of information. In a passage that calls to mind Susan Sontag’s monumental 1964 case against interpretation — for whom Benjamin was an influence; “Re-read … [Walter] Benjamin essays, often!” she wrote in her diary, where she extolled the virtues of rereading — he adds:

Every morning brings us the news of the globe, and yet we are poor in noteworthy stories. This is because no event any longer comes to us without already being shot through with explanation. In other words, by now almost nothing that happens benefits storytelling; almost everything benefits information. Actually, it is half the art of storytelling to keep a story free from explanation as one reproduces it… The most extraordinary things, marvelous things, are related with the greatest accuracy, but the psychological connection of the events is not forced on the reader. It is left up to him to interpret things the way he understands them, and thus the narrative achieves an amplitude that information lacks.[…]The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was new. It lives only at that moment; it has to surrender to it completely and explain itself to it without losing any time. A story is different. It does not expend itself. It preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time.

But the most perilous byproduct of the cult of information, and the greatest threat to storytelling, is something Benjamin identifies a century ago in such a way that any thinking person instantly recognizes it as triply troublesome today: our allergy to boredom and the resulting lost art of stillness. Boredom, after all, is the crucible of contemplation and creativity — legendary psychoanalyst Adam Phillips called the capacity for boredom “a developmental achievement for the child” and argued that it is essential for the creative life; philosopher Bertrand Russell saw it as central to the conquest of happiness; in his semantic sparring match, Kierkegaard first renounced it, only to extol its sister virtue of idleness. And yet today, we have lost all capacity for boredom. More than that, we have grown bored with thinking itself — we want to instantly know. We want ready-made information to fill the void of contemplative wisdom.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from 'Open House for Butterflies' by Ruth Krauss. Click image for more.

Benjamin caught the early symptoms of this civilizational malady and peered into its future metastasis with extraordinary prescience and precision. He argues for the importance of boredom in the art of listening between the lines, which is in turn central to storytelling:

There is nothing that commends a story to memory more effectively than that chaste compactness which precludes psychological analysis. And the more natural the process by which the storyteller forgoes psychological shading, the greater becomes the story’s claim to a place in the memory of the listener, the more completely is it integrated into his own experience, the greater will be his inclination to repeat it to someone else someday, sooner or later. This process of assimilation, which takes place in depth, requires a state of relaxation which is becoming rarer and rarer. If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away. His nesting places — the activities that are intimately associated with boredom — are already extinct in the cities and are declining in the country as well. With this the gift for listening is lost and the community of listeners disappears. For storytelling is always the art of repeating stories, and this art is lost when the stories are no longer retained. It is lost because there is no more weaving and spinning to go on while they are being listened to. The more self-forgetful the listener is, the more deeply is what he listens to impressed upon his memory. When the rhythm of work has seized him, he listens to the tales in such a way that the gift of retelling them comes to him all by itself. This, then, is the nature of the web in which the gift of storytelling is cradled. This is how today it is becoming unraveled at all its ends after being woven thousands of years ago in the ambience of the oldest forms of craftsmanship.

In a sentiment that calls to mind the only surviving recording of Virginia Woolf’s voice and Mary Oliver’s memorable assertion that “attention without feeling … is only a report,” Benjamin considers this craftsmanship aspect of storytelling:

The storytelling that thrives … is itself an artisan form of communication, as it were. It does not aim to convey the pure essence of the thing, like information or a report. It sinks the thing into the life of the storyteller, in order to bring it out of him again. Thus traces of the storyteller cling to the story the way the handprints of the potter cling to the clay vessel.

In yet another stroke of sublime divination, Benjamin quotes legendary French polymath Paul Valéry’s assertion that “modern man no longer works at what cannot be abbreviated” — prescient commentary on our modern lust for listicles, the ultimate form of abbreviation — and writes:

[Man] has succeeded in abbreviating even storytelling… From oral tradition and no longer permits that slow piling one on top of the other of thin, transparent layers which constitutes the most appropriate picture of the way in which the perfect narrative is revealed through the layers of a variety of retellings.

Citing Valéry again — who argued that an artisan’s work gets its “existence and value exclusively from a certain accord of the soul, the eye” — Benjamin returns to the craftsmanship aspect of storytelling with its implicit call for patience, which is even more endangered in our day than it was in his:

Soul, eye, and hand are brought into connection. Interacting with one another, they determine a practice. We are no longer familiar with this practice. The role of the hand in production has become more modest, and the place it filled in storytelling lies waste… That old co-ordination of the soul, the eye, and the hand … is that of the artisan which we encounter wherever the art of storytelling is at home. In fact, one can go on and ask oneself whether the relationship of the storyteller to his material, human life, is not in itself a craftsman’s relationship, whether it is not his very task to fashion the raw material of experience, his own and that of others, in a solid, useful, and unique way.

And therein lies the very point that makes Benjamin’s meditation so timely and so unshakably urgent today — this fashioning of experience into something “solid” and “useful” for human life is precisely the transmutation of information into wisdom that we, a century after Benjamin, are increasingly losing and desperately need. Benjamin writes:

Seen in this way, the storyteller joins the ranks of the teachers and sages. He has counsel — not for a few situations, as the proverb does, but for many, like the sage. For it is granted to him to reach back to a whole lifetime (a life, incidentally, that comprises not only his own experience but no little of the experience of others; what the storyteller knows from hearsay is added to his own). His gift is the ability to relate his life; his distinction, to be able to tell his entire life. The storyteller: he is the man who could let the wick of his life be consumed completely by the gentle flame of his story. This is the basis of the incomparable aura about the storyteller… The storyteller is the figure in which the righteous man encounters himself.

The full essay, in its eighteen-page entirety, is well worth reading, as is the rest of Benjamin’s wildly and widely rewarding Illuminations. Complement it with Benjamin’s thirteen commandments of writing and Nabokov on the three qualities of a great storyteller.

No comments:

Post a Comment