Trailblazing Philosopher Susanne Langer on How Our Questions Shape Our Answers and Direct Our Orientation of Mind

Maria Popova

“To maintain the state of doubt and to carry on systematic and protracted inquiry — these are the essentials of thinking,” John Dewey wrote in his increasingly timely 1910 meditation on how to cultivate reflective curiosity in an age of instant opinions. But the mechanisms by which we seek to resolve our doubt too often curtail our inquiry rather than protracting it — unsettled by uncertainty, we rush to answers that contract our questions rather than expanding our curiosity. Krista Tippett, one of the great question-expanders of our time, captures this beautifully: “Answers mirror the questions they rise, or fall, to meet.”

No one has addressed this osmotic relationship between question and answer more incisively than Susanne Langer (December 20, 1895–July 17, 1985) — one of modernity’s first women philosophers, whose work in philosophy of mind and philosophy of art has influenced generations of thinkers.

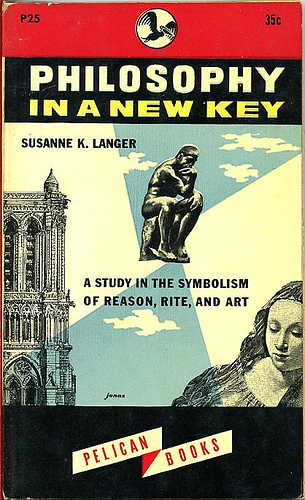

Langer writes in her magnificent 1942 book Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art (public library):

The “technique,” or treatment, of a problem begins with its first expression as a question. The way a question is asked limits and disposes the ways in which any answer to it — right or wrong — may be given. If we are asked: “Who made the world?” we may answer: “God made it,” “Chance made it,” “Love and hate made it,” or what you will. We may be right or we may be wrong. But if we reply: “Nobody made it,” we will be accused of trying to be cryptic, smart, or “unsympathetic.” For in this last instance, we have only seemingly given an answer; in reality we have rejected the question. The questioner feels called upon to repeat his problem. “Then how did the world become as it is?” If now we answer: “It has not ‘become’ at all,” he will be really disturbed. This “answer” clearly repudiates the very framework of his thinking, the orientation of his mind, the basic assumptions he has always entertained as commonsense notions about things in general. Everything has become what it is; everything has a cause; every change must be to some end; the world is a thing, and must have been made by some agency, out of some original stuff, for some reason.

In a sentiment which Hannah Arendt, another female trailblazer of intellectual life, would echo a generation later in her invigorating treatise on the life of the mind and the crucial distinction between thinking and knowing, Langer considers this tendency to reject the question with a non-answer:

These are natural ways of thinking. Such implicit “ways” are not avowed by the average man, but simply followed. He is not conscious of assuming any basic principles. They are what a German would call his “Weltanschauung,” his attitude of mind, rather than specific articles of faith. They constitute his outlook; they are deeper than facts he may note or propositions he may moot.

But, though they are not stated, they find expression in the forms of his questions. A question is really an ambiguous proposition; the answer is its determination. There can be only a certain number of alternatives that will complete its sense. In this way the intellectual treatment of any datum, any experience, any subject, is determined by the nature of our questions, and only carried out in the answers.

Many decades later, Philosophy in a New Key remains an intellectually electrifying and abidingly rewarding read. Complement it with John Dewey on how we think, René Descartes’s twelve timeless tenets of critical thinking, and Simone Weil on the purest and most fertile form of thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment