Privilege And Pressure: A Memoir Of Growing Up Black And Elite In 'Negroland'

NPR

http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/09/08/438536006/privilege-and-pressure-a-memoir-of-growing-up-black-and-elite-in-negrolandExcerpt: "Nothing highlighted our privilege more than the menace to it. Inside the race we were the self-designated aristocrats, educated, affluent, accomplished; to Caucasians we were oddities, underdogs and interlopers. White people who, like us, had manners, money, and education… But wait: “Like us” is presumptuous for the 1950s. Liberal whites who saw that we too had manners, money, and education lamented our caste disadvantage. Less liberal or non-liberal whites preferred not to see us in the private schools and public spaces of their choice. They had ready a bevy of slights: from skeptics the surprised glance and spare greeting; from waverers the pleasantry, eyes averted; from disdainers the direct cut. Caucasians with materially less than us were given license by Caucasians with more than them to subvert and attack our privilege. Caucasian privilege lounged and sauntered, draped itself casually about, turned vigilant and commanding, then cunning and devious. We marveled at its tonal range, its variety, its largesse in letting its humble share the pleasures of caste with its mighty. We knew what was expected of us. Negro privilege had to be circumspect: impeccable but not arrogant; confident yet obliging; dignified, not intrusive."

“You’ve got to tell the world how to treat you,” James Baldwin told Margaret Mead in their revelatory conversation on power and privilege. “If the world tells you how you are going to be treated, you are in trouble.” The many modes of telling and the many types of trouble are what trailblazing journalist, longtime New York Times theater critic, and Pulitzer winner Margo Jefferson (b. October 17, 1947) explores in Negroland: A Memoir (public library) — a masterwork of both form and substance.

Jefferson transforms her experience of growing up in an affluent black family into a lens on the broader perplexities of privilege and its provisional nature. Her piercing cultural insight unfolds in uncommonly beautiful writing, both honoring the essence of the memoir form — a vehicle for reaching the universal from the outpost of the personal — and defying its conventions through enlivening narrative experimentation.

Jefferson, who came of age in an era when the biological fallacies of racial difference still ran rampant, writes:

I was taught to avoid showing off.

I was taught to distinguish myself through presentation, not declaration, to excel through deeds and manners, not showing off.But isn’t all memoir a form of showing off?In my Negroland childhood, this was a perilous business.Negroland is my name for a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty. Children in Negroland were warned that few Negroes enjoyed privilege or plenty and that most whites would be glad to see them returned to indigence, deference, and subservience. Children there were taught that most other Negroes ought to be emulating us when too many of them (out of envy or ignorance) went on behaving in ways that encouraged racial prejudice.Too many Negroes, it was said, showed off the wrong things: their loud voices, their brash and garish ways; their gift for popular music and dance, for sports rather than the humanities and sciences. Most white people were on the lookout, we were told, for what they called these basic racial traits. But most white people were also on the lookout for a too-bold display by us of their kind of accomplishments, their privilege and plenty, what they considered their racial traits. You were never to act undignified in their presence, but neither were you to act flamboyant. Showing off was permitted, even encouraged, only if the result reflected well on your family, their friends, and your collective ancestors.

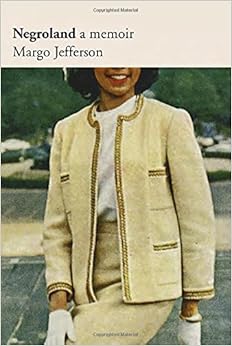

Jefferson and her older sister in Canada, during the family’s 1956 cross-country road trip.

What is perhaps most disorienting about visibilia like race, age, and gender is that they externalize the inner contradictions with which we live — those tug-of-wars between dignity and self-doubt, between the yearning to belong and the fear that we don’t. Jefferson captures these dimensions beautifully:

Nothing highlighted our privilege more than the menace to it. Inside the race we were the self-designated aristocrats, educated, affluent, accomplished; to Caucasians we were oddities, underdogs and interlopers. White people who, like us, had manners, money, and education… But wait: “Like us” is presumptuous for the 1950s. Liberal whites who saw that we too had manners, money, and education lamented our caste disadvantage. Less liberal or non-liberal whites preferred not to see us in the private schools and public spaces of their choice. They had ready a bevy of slights: from skeptics the surprised glance and spare greeting; from waverers the pleasantry, eyes averted; from disdainers the direct cut. Caucasians with materially less than us were given license by Caucasians with more than them to subvert and attack our privilege.

Caucasian privilege lounged and sauntered, draped itself casually about, turned vigilant and commanding, then cunning and devious. We marveled at its tonal range, its variety, its largesse in letting its humble share the pleasures of caste with its mighty. We knew what was expected of us. Negro privilege had to be circumspect: impeccable but not arrogant; confident yet obliging; dignified, not intrusive.

Among the most poignant threads in Jefferson’s cultural memoir is the paradoxical notion of privilege earned. Privilege, after all, is granted by definition — earned privilege is the simulacrum of privilege, staked at the entrance to the power club and demanding the price of admission: endless self-contortion.

A self-described “chronicler of Negroland, a participant-observer, an elegist, dissenter and admirer; sometime expatriate, ongoing interlocutor,” Jefferson writes:

That’s the generic version of a story. Here’s the specific version: the midwestern, midcentury story of a little girl, one of two born to an attractive couple pleased with their lives and achievements, wanting the best for their children and wanting their children to be among the best.

To be successful, professionally and personally.And to be happy.Children always find ways to subvert while they’re busy complying. This child’s method of subversion? She would achieve success, but she would treat it like a concession she’d been forced to make. For unto whomsoever much is given, of her shall be much required. She came to feel that too much had been required of her. She would have her revenge. She would insist on an inner life regulated by despair… She embraced her life up to a point, then rejected it, and from that rejection have come all her difficulties.

See more here.

No comments:

Post a Comment