Seventh District US Congressional Republican candidate, David Brat displays an immigration mailer by Congressman Eric Cantor during a press conference at the Capitol in Richmond, Va., Wednesday, May 28, 2014. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

***

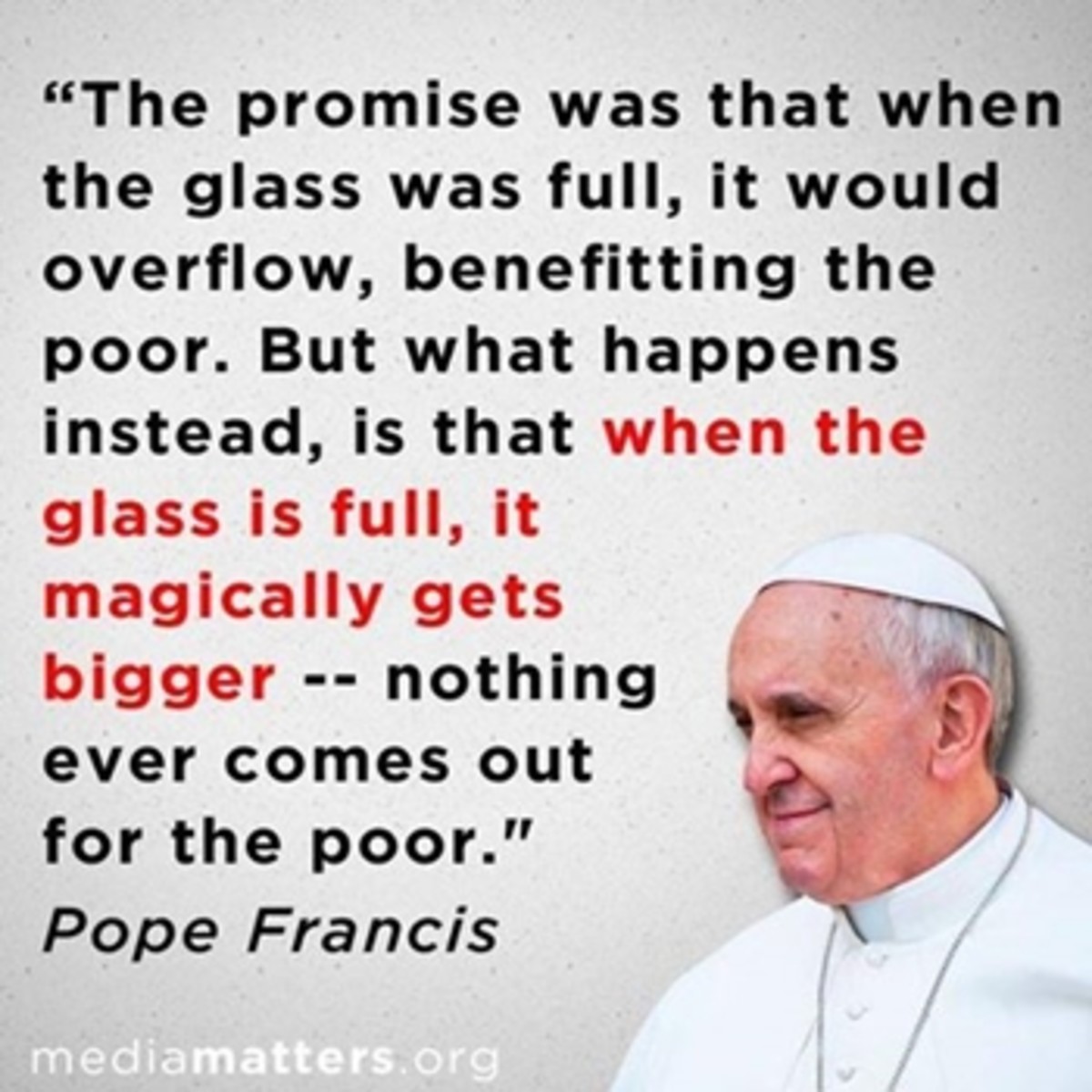

Pope Francis Links

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2013/11/pope-francis-links.html

***

Dave Brat’s unorthodox economics: Adam Smith ‘was from a red state’

Tea Party candidate Dave Brat defeated House Majority leader Eric Cantor (R-Va.) last night in a stunning defeat in a GOP Virginia primary. Brat's background is as economics professor at Randolph-Macon college, but his work is fairly unique and unorthodox in a profession that tends toward the opposite.

So what are Brat's economic beliefs? Well, he's focused on, to his mind, two related questions: why rich countries are so rich, and what ethics has to do with economics. Let's look at them both.

What makes countries rich, according to Brat

Like all economists, Brat talks about technology when he talks about long-term growth. His 1996 paper "Cross-Country R&D and Growth: Variations on a Theme of Mankiw-Romer-Weil" looks at how differences in research spending help explain differences in wealth. The tricky thing, though, is that new inventions don't just stay where they were invented—there are "spillovers." So will more R&D in rich countries make all countries more or less equal? "An unambiguous answer," Brat concludes, "cannot be given."

But innovation isn't just about R&D. It's also about the kinds of institutions that can encourage and sustain it. Brat's 2004 paper, "All Democracies Created Equal? 195 Years Might Matter," argues that countries that have been democratic for longer tend to grow faster than others. Though he "found the positive relationship we were expecting," Brat concedes that he's "not confident that our result is robust across all specifications." In other words, it's not a statistical slam dunk.

Brat on ethics and capitalism

Brat tries to take this kind of historical argument even further by reviving Max Weber's thesis about the Protestant ethic and the rise of capitalism. "Give me a country in 1600 that had a Protestant led contest for religious and political power," he writes, "and I will show you a country that is rich today"—discounting the idea that this is a spurious correlation.

In short, Brat thinks that culture matters—and so does ethics. Now, that's not a word you hear economists use very much nowadays, but Brat points out that they used to. In an unpublished 2005 paper, he insists that "[Adam] Smith was from a red state," because "the culture and context which produced him was overwhelmingly Protestant."

This meant, according to Brat, that unlike economists today, Smith "knew that the world of thought must be unified"—that "positive analysis and normative analysis must meet in the end." In other words, Brat thinks economists have to get back to telling us how to live, and not just how to live efficiently. Or at least be explicit about it, so we can judge whether we like the ethics behind their economics.

As Zach Beauchamp points out, Brat thinks that most economists have smuggled a utilitarian ethic—maximizing the most good for the most people—into economic analysis, without debating whether there are other, better ethics.

Alan: Like most Christian conservatives, Brat voices no concern for "structural sin," believing instead that all solutions arise from "preaching the gospel" in order to "change hearts and minds." In this constricted view, there is no need to enact direct political remedies - in addition to personal reformation. In fact, human affairs are both personal and social so that rugged individualism's exclusive focus on "the personal" denies the necessary polarity of existence itself. Without two poles, ideologues routinely resort to absolutism, thus gladdening the hearts of corporatists while simultaneously ensuring the prolongation - indeed, the exacerbation -- of inequalities.

Conservative Christians ignore Christendom's bedrock belief in "the disciplines of virtue" thus exempting themselves from any collective responsibility beyond the scope of family and local congregation.

John Kenneth Galbraith put it best:

We are our brother's keeper and no amount of specious self-aggrandizement will vacate that truth.

What would be a better ethic? Well, for Brat that's simple enough: Christianity. He realizes that markets can fail, but he doesn't think regulation is the answer. He thinks religion is. "If markets are bad, which they are, that means people are bad, which they are," he says in a 2011 paper. The answer is to "preach the gospel and change hearts and souls," so we can "make all of the people good"—which means "markets will be good" too.

Not exactly Dodd-Frank.

Matt O'Brien is a reporter for Wonkblog covering economic affairs. He was previously a senior associate editor at The Atlantic.

No comments:

Post a Comment