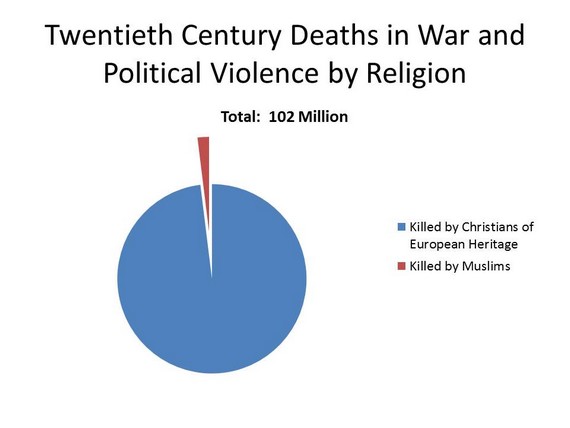

Alan: In the United States, it is well-documented that people who regularly go to church are happier than those who don't. It is also documented that the political views of American religious practitioners make the following chart completely comprehensible:

"Terrorism and The Other Religions"

Juan Cole

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2014/04/terrorism-and-other-religions-juan-cole.html

***

Hipsters and Squares: Psychologist Jerome Bruner on Myth, Identity, “Creative Wholeness” and How We Limit Our Happiness

by Maria Popova

How our cult of creativity, which replaced religion, is becoming a source of anguish rather than happiness.

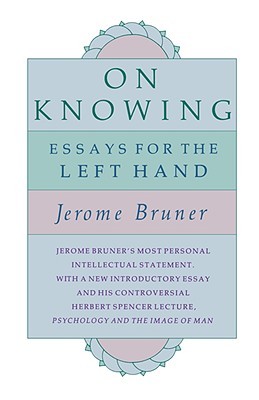

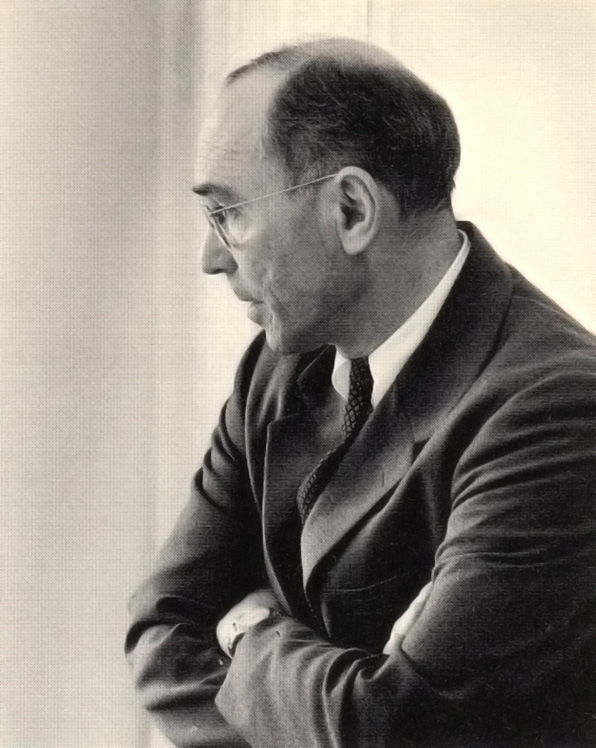

Today, we hang so much of our identity on our capacity to create, often confusing what we dofor who we are. And while creativity, by and large, is a positive force in the external world, its blind pursuit can be damaging to the inner. So admonishes the influential Harvard psychologist Jerome Bruner (b. October 1, 1915), celebrated for his contributions to cognitive psychology and learning theory in education, in his altogether fantastic 1962 anthology On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand (public library) — the same wonderful collection of essays that gave us Bruner’s theory of “effective surprise” and the 6 essential conditions for creativity. One of the essays, titled “Myth and Identity,” explores precisely that relationship between our modern myths, which shape our beliefs about creativity and happiness, and our often conflicted sense of identity.

Today, we hang so much of our identity on our capacity to create, often confusing what we dofor who we are. And while creativity, by and large, is a positive force in the external world, its blind pursuit can be damaging to the inner. So admonishes the influential Harvard psychologist Jerome Bruner (b. October 1, 1915), celebrated for his contributions to cognitive psychology and learning theory in education, in his altogether fantastic 1962 anthology On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand (public library) — the same wonderful collection of essays that gave us Bruner’s theory of “effective surprise” and the 6 essential conditions for creativity. One of the essays, titled “Myth and Identity,” explores precisely that relationship between our modern myths, which shape our beliefs about creativity and happiness, and our often conflicted sense of identity.

Bruner begins with some essential definitions:

Myth … is at once an external reality and the resonance of the internal vicissitudes of man.

But while he acknowledges that the central function of myth is “to effect some manner of harmony between the literalities of experience and the night impulses of life,” Bruner cautions against assuming an opposition of the two — of “the grammar of experience and the grammar of myth” — as they are complementary rather than clashing, something best manifested in the relationship between myth and personality. Bruner writes:

Consider first myth as projection, to use the conventional psychoanalytic term. I would prefer the term “externalization” better to make clear that we are dealing here with … the human preference to cope with events that are outside rather than inside. Myth, insofar as it is fitting, provides a ready-made means of externalizing human plight by embodying and representing them in storied plot and characters.

Externalizing our inner life in such a way, Bruner argues, provides a “basis for communion” among us:

By the subjectifying of our worlds through externalization, we are able, paradoxically enough, to share communally in the nature of internal experience.

It also enables us to work through our inner turmoils in a unique way, something Adam Phillips echoed more than half a century later in reflecting onthe parallels between psychoanalysis and storytelling. Bruner puts it elegantly as he considers the defining psychic malady of our time:

If one is to contain the panicking spread of anxiety, one must be able to identify and put a comprehensible label upon one’s feelings better to treat them again, better to learn from experience… Myth, perhaps, serves in place of or as a filter for experiences.[…]What is the art form of myth? Principally it is drama; yet for all its concern with preternatural forces and characters, it is realistic drama that … tells of “origins and destinies”… Knowing through art has the function of connecting through metaphor what before had no apparent kinship [and] the art form of the myth connects the daemonic world of impulse with the world of reason by a verisimilitude that conforms to each.

Considering the early myths — those of Ancient Greece and the Christian tradition — Bruner points to two key mythic plots that emerge in the struggle to give shape to our experiences: “the plot of innocence and the plot of cleverness.” But modernity, he argues, has thrown into tumult both ideals, resulting in an “internal clamor of identities” that ends up threatening our happiness and our capacity for creative fulfillment.

Illustration from 'The Iliad and the Odyssey: A Giant Golden Book' by Alice and Martin Provensen. Click image for details.

In one particularly prescient passage, Bruner writes:

In our own time, in the American culture, there is a deep problem generated by the confusion that has befallen the myth of the happy [person]… We are no longer a “mythologically instructed community.” And so one finds a new generation struggling to find or to create a satisfactory and challenging mythic image.Two such images seem to be emerging in the new generation. One is that of the hipsters and the squares; the other is the idealization of creative wholeness. The first is the myth of the uncommitted wandering hero, capable of the hour’s subjectivity — its “kicks” — participating in a new inwardness. It is the theme of reduction to the essential persona, the hero able to filter out the clamors of an outside world, an almost masturbatory ideal.

Bruner points to the original “hipsters” and notes the similarity between the mythmaking of real-life identity and that of character in fiction:

It is not easy to create a myth and to emulate it at the same time. James Dean and Jack Kerouac, Kingsley Amis and John Osborne, the Teddy Boys and the hipsters: they do not make a mythological community. They represent mythmaking in process as surely as Hemingway’s characters or Scott Fitzgerald’s.

Bruner considers one especially toxic and limiting myth — that of “the full creative [person],” a notion all the more zealously pursued in our present age of endless creativity conferences, spiritual retreats for corporate executives, and workplaces that seek to disguise a cubicle farm as a hybrid of playground and university. Bruner describes the ancestry of our modern condition:

It is … the middle-aged executive sent back to the university by the company for a year, wanting humanities and not sales engineering; it is this man telling you that he would rather take life classes Saturday morning at the museum school than be president of the company; it is the adjectival extravaganza of the word “creative,” as in “creative advertising.” It is as if, given the demise of the myths of creation and their replacement by a scientific cosmogony that for all its formal beauty lacks metaphoric force, the theme of creating becomes internalized, creating anguish rather than, as in the externalized myths, providing a basis for psychic relief and sharing. Yet this self-contained image of creativity becomes, I think, the basis for a myth of happiness. But perhaps between the death of one myth and the birth of its replacement there must be a reinternalization, even to the point of [a cult of the ego]. That we cannot yet know. All that is certain is that we live in a period of mythic confusion that may provide the occasion for a new growth of myth, myth more suitable for our times.

One is left wondering whether our present time is one of reconciliation or of even greater “mythic confusion.”

On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand is a magnificent read in its entirety, further exploring questions of creativity, identity, metaphor, and the role of art in the human experience. Complement with Maya Angelou on the internalization of identity.

No comments:

Post a Comment