C.S. Lewis on the Three Ways of Writing for Children and the Key to Authenticity in All Writing

by Maria Popova

“The only moral that is of any value is that which arises inevitably from the whole cast of the author’s mind.”

“I don’t write for children,” the late and great Maurice Sendak said in his final interview. “I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’”J.R.R. Tolkien had memorably articulated the same sentiment seven decades earlier, in asserting that there is no such thing as writing “for children,” and Neil Gaiman eloquently echoed it in a recent interview. But perhaps the greatest and most ardent advocate for this notion was C.S. Lewis.

“I don’t write for children,” the late and great Maurice Sendak said in his final interview. “I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’”J.R.R. Tolkien had memorably articulated the same sentiment seven decades earlier, in asserting that there is no such thing as writing “for children,” and Neil Gaiman eloquently echoed it in a recent interview. But perhaps the greatest and most ardent advocate for this notion was C.S. Lewis.

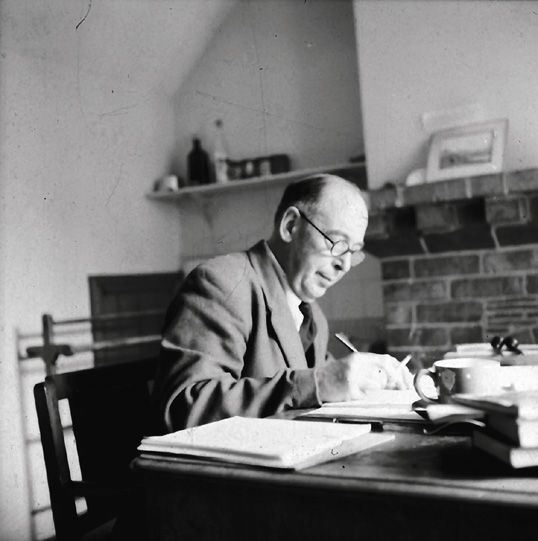

In the spring of 1952, Lewis delivered a magnificent and wonderfully dogma-defiant talk at the Library Association titled “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” eventually adapted into an essay and published in Lewis’s Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (public library).

Lewis begins by outlining the trifecta of approaches:

I think there are three ways in which those who write for children may approach their work; two good ways and one that is generally a bad way.I came to know of the bad way quite recently and from two unconscious witnesses. One was a lady who sent me the [manuscript] of a story she had written in which a fairy placed at a child’s disposal a wonderful gadget. I say ‘gadget’ because it was not a magic ring or hat or cloak or any such traditional matter. It was a machine, a thing of taps and handles and buttons you could press. You could press one and get an ice cream, another and get a live puppy, and so forth. I had to tell the author honestly that I didn’t much care for that sort of thing. She replied, ‘No more do I, it bores me to distraction. But it is what the modern child wants.’ My other bit of evidence was this. In my own first story I had described at length what I thought a rather fine high tea given by a hospitable faun to the little girl who was my heroine. A man, who has children of his own, said, ‘Ah, I see how you got to that. If you want to please grown-up readers you give them sex, so you thought to yourself, “That won’t do for children, what shall I give them instead? I know! The little blighters like plenty of good eating.” In reality, however, I myself like eating and drinking. I put in what I would have liked to read when I was a child and what I still like reading now that I am in my fifties.The lady in my first example, and the married man in my second, both conceived writing for children as a special department of ‘giving the public what it wants’. Children are, of course, a special public and you find out what they want and give them that, however little you like it yourself.

Illustration for Hans Christian Andersen's 'The Darning Needle' by Maurice Sendak, 1959. Click image for details.

Lewis counters this with the first of the two “good ways,” which may bear a superficial resemblance to the “bad” but is in actuality fundamentally different. This is the way of storytellers like Lewis Carroll and J.R.R. Tolkien, whose published work “grows out of a story told to a particular child with the living voice and perhaps ex tempore” — in Carroll’s case, little Alice Liddell, and in Tolkien’s, his own children. While this, too, may be a case of giving a child what he or she wants, the fact that it is a particular child means the author makes no attempt to treat all children like a “special public.” Lewis writes:

There is no question of “children” conceived as a strange species whose habits you have “made up” like an anthropologist or a commercial traveller. Nor, I suspect, would it be possible, thus face to face, to regale the child with things calculated to please it but regarded by yourself with indifference or contempt. The child, I am certain, would see through that. In any personal relation the two participants modify each other. You would become slightly different because you were talking to a child and the child would become slightly different because it was being talked to by an adult. A community, a composite personality, is created and out of that the story grows.

He follows this with the final “way” of writing for children, that of his own preference:

The third way, which is the only one I could ever use myself, consists in writing a children’s story because a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say: just as a composer might write a Dead March not because there was a public funeral in view but because certain musical ideas that had occurred to him went best into that form.[…]Where the children’s story is simply the right form for what the author has to say, then of course readers who want to hear that, will read the story or re-read it, at any age… I am almost inclined to set it up as a canon that a children’s story which is enjoyed only by children is a bad children’s story. The good ones last. A waltz which you can like only when you are waltzing is a bad waltz.

Illustration for the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen by Japanese artist Takeo Takei, 1928. Click image for details.

But Lewis’s most powerful point has less to do with the particular art-form of children’s literature and more to do with a broader cultural pathology. In discussing the fate of fantasy and fairy tales in society and in the hands of critics, he touches on our general tendency to treat adulthood as superior to childhood, a sort of existential upgrade, using childishness as a put-down and seeing immaturity as a negative quality. Lewis writes:

Critics who treat adult as a term of approval, instead of as a merely descriptive term, cannot be adult themselves. To be concerned about being grown up, to admire the grown up because it is grown up, to blush at the suspicion of being childish; these things are the marks of childhood and adolescence. And in childhood and adolescence they are, in moderation, healthy symptoms. Young things ought to want to grow. But the on into middle life or even into early manhood this concern about being adult is a mark of really arrested development: When I was ten I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.

He extends this to how we evaluate our creative and intellectual “growth” over the course of life:

The modern view seems to me to involve a false conception of growth. They accuse us of arrested development because we have not lost a taste we had in childhood. But surely arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new things? I now like hock, which I am sure I should not have liked as a child. But I still like lemon-squash. I call this growth or development because I have been enriched: where I formerly had only one pleasure, I now have two. But if I had to lose the taste for lemon-squash before I acquired the taste for hock, that would not be growth but simple change. I now enjoy Tolstoy and Jane Austen and Trollope as well as fairy tales and I call that growth: if I had had to lose the fairy tales in order to acquire the novelists, I would not say that I had grown but only that I had changed.

Just like every generation reports the alleged death of the novel, Lewis argues that “about once every hundred years some wiseacre gets up and tries to banish the fairy tale.” In a passage especially prescient in our age when fanciful untruths like creationism are still taught in classrooms, Lewis writes:

[The fairy tale] is accused of giving children a false impression of the world they live in. But I think no literature that children could read gives them less of a false impression. I think what profess to be realistic stories for children are far more likely to deceive them. I never expected the real world to be like the fairy tales. I think that I did expect school to be like the school stories. The fantasies did not deceive me: the school stories did. All stories in which children have adventures and successes which are possible, in the sense that they do not break the laws of nature, but almost infinitely improbable, are in more danger than the fairy tales of raising false expectations…This distinction holds for adult reading too. The dangerous fantasy is always superficially realistic. The real victim of wishful reverie does not batten on the Odyssey, The Tempest, or The Worm Ouroboros: he (or she) prefers stories about millionaires, irresistible beauties, posh hotels, palm beaches and bedroom scenes—things that really might happen, that ought to happen, that would have happened if the reader had had a fair chance. For, as I say, there are two kinds of longing. The one is an askesis, a spiritual exercise, and the other is a disease.

Lewis concludes with a beautiful and urgently important sentiment that applies as much to writing for children as it does to all writing, especially in our age ofquestionable motives for the written word, and perhaps most of all to life itself. It’s a poignant reminder that everything we put into the world is invariably the sum total of our lived experience and our personhood, and our journey, to attempt to sculpt the end result into something different would be not only an act of hypocrisy but also, inevitably, a guarantee of mediocrity. Lewis writes:

I rejected any approach which begins with the question ‘What do modern children like?’ I might be asked, ‘Do you equally reject the approach which begins with the question “What do modern children need?” — in other words, with the moral or didactic approach?’ I think the answer is Yes. Not because I don’t like stories to have a moral: certainly not because I think children dislike a moral. Rather because I feel sure that the question ‘What do modern children need?’ will not lead you to a good moral. If we ask that question we are assuming too superior an attitude. It would be better to ask ‘What moral do I need?’ for I think we can be sure that what does not concern us deeply will not deeply interest our readers, whatever their age. But it is better not to ask the question at all. Let the pictures tell you their own moral. For the moral inherent in them will rise from whatever spiritual roots you have succeeded in striking during the whole course of your life. But if they don’t show you any moral, don’t put one in. For the moral you put in is likely to be a platitude, or even a falsehood, skimmed from the surface of your consciousness. It is impertinent to offer the children that. For we have been told on high authority that in the moral sphere they are probably at least as wise as we. Anyone who can write a children’s story without a moral, had better do so: that is, if he is going to write children’s stories at all. The only moral that is of any value is that which arises inevitably from the whole cast of the author’s mind.Indeed everything in the story should arise from the whole cast of the author’s mind. We must write for children out of those elements in our own imagination which we share with children: differing from our child readers not by any less, or less serious, interest in the things we handle, but by the fact that we have other interests which children would not share with us. The matter of our story should be a part of the habitual furniture of our minds.

All of the writing in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories is absolutely fantastic, spanning everything from the nature of storytelling to why writers should read criticism of their own work to the role of science fiction in society. Complement it with Lewis’s letters to children on the secret of happiness and the only three duties in life.

No comments:

Post a Comment