"Life, Loss And The Wisdom Of Rivers"

Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

“The past only comes back when the present runs so smoothly that it is like the sliding surface of a deep river,”Virginia Woolf wrote some years before she filled her coat-pockets with stones, waded into the River Ouse near her house, and, unwilling to endure what she had barely survived in the past, slid beneath the smooth surface of life.

One midsummer morning seven decades after Woolf was swallowed by the Ouse, Olivia Laing set out to walk the river’s banks from source to sea while navigating her own upheaval of the soul in the wake of heartbreak. She recorded her forty-two-mile existential expedition in To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface (public library) — one of those stunning, unclassifiable, uncommonly poetic books that seep into crevices of your psyche you didn’t know existed and settle into the groundwater of your being.

Laing writes:

I am haunted by waters. It may be that I’m too dry in myself, too English, or it may be simply that I’m susceptible to beauty, but I do not feel truly at ease on this earth unless there’s a river nearby. “When it hurts,” wrote the Polish poet Czeslaw Miłosz, “we return to the banks of certain rivers,” and I take comfort in his words, for there’s a river I’ve returned to over and again, in sickness and in health, in grief, in desolation and in joy.

Laing examines the particular pull of the Ouse and its riverine stretch across “233 square miles of land the shape of a collapsed lung,” haunted by Woolf yet animated by some singular spirit of its own:

For a while I used to swim with a group of friends at South-ease, near where her body was found. I’d enter the swift water in trepidation that gave way to ecstasy, tugged by a current that threatened to tumble me beneath the surface and bowl me clean to the sea. The river passed in that region through a chalk valley ridged by the Downs, and the chalk seeped into the water and turned it the milky green of sea glass, full of little shafts of imprisoned light. You couldn’t see the bottom; you could barely make out your own limbs, and perhaps it was this opacity which made it seem as though the river was the bearer of secrets: that beneath its surface something lay concealed.

It wasn’t morbidity that drew me to that dangerous place but rather the pleasure of abandoning myself to something vastly beyond my control. I was pulled to the Ouse as a magnet is pulled to metal, returning on summer nights and during the short winter days to repeat some walks, some swims through turning seasons until they amassed the weight of ritual.

Reflecting on the cataclysm that thrust her toward this riverine journey — “one of those minor crises that periodically afflict a life, when the scaffolding that sustains us seems destined to collapse” — and the aim of her unusual experiment, Laing writes:

I wanted somehow to get beneath the surface of the daily world, as a sleeper shrugs off the ordinary air and crests towards dreams.

Rivers may be among our richest existential metaphors — “Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river,” Borges proclaimed in his timeless meditation on time; “I do not think that the banks of a river suffer because they let the river flow,” Frida Kahlo wrote in celebrating her unconventional relationship with Diego Rivera — but they are also the raw material of our existence, the seedbed of civilization. Laing writes:

A river passing through a landscape catches the world and gives it back redoubled: a shifting, glinting world more mysterious than the one we customarily inhabit. Rivers run through our civilisations like strings through beads, and there’s hardly an age I can think of that’s not associated with its own great waterway. The lands of the Middle East have dried to tinder now, but once they were fertile, fed by the fruitful Euphrates and the Tigris, from which rose flowering Sumer and Babylonia. The riches of Ancient Egypt stemmed from the Nile, which was believed to mark the causeway between life and death, and which was twinned in the heavens by the spill of stars we now call the Milky Way. The Indus Valley, the Yellow River: these are the places where civilisations began, fed by sweet waters that in their flooding enriched the land. The art of writing was independently born in these four regions and I do not think it a coincidence that the advent of the written word was nourished by river water.

Native boat, Kongo River, circa 1915 (public domain)

But whatever rivers may nurture with their physical presence, Laing argues, they also foment some essential metaphysical part of our humanity:

There is a mystery about rivers that draws us to them, for they rise from hidden places and travel by routes that are not always tomorrow where they might be today. Unlike a lake or sea, a river has a destination and there is something about the certainty with which it travels that makes it very soothing, particularly for those who’ve lost faith with where they’re headed.

[…]A river moves through time as well as space. Rivers have shaped our world; they carry with them, as Joseph Conrad had it, “the dreams of men, the seed of commonwealths, the germs of empires.” Their presence has always lured people, and so they bear like litter the cast-off relics of the past.

Echoing Woolf’s metaphor of the river as the permeable boundary between the present and the past, Laing writes:

At times, it feels as if the past is very near. On certain evenings, when the sun has dropped and the air is turning blue, when barn owls float above the meadow grass and a pared-down moon breaches the treeline, a mist will sometimes lift from the surface of the river. It is then that the strangeness of water becomes apparent. The earth hoards its treasures and what is buried there remains until it’s disinterred by spade or plough, but a river is more shifty, relinquishing its possessions haphazardly and without regard to the landlocked chronology historians hold so dear. A history compiled by way of water is by its nature quick and fluid, full of submerged life and capable, as I would discover, of flooding unexpectedly into the present.

Illustration from The River by Alessandro Sanna

The supreme allure of rivers may be the intoxicating interplay between what they reveal and what they conceal, and that may also be what makes the river such a wellspring of metaphors — for, as Nietzsche well knew, this duality is at the heart of every potent metaphor. In consonance with astrophysicist Janna Levin’s beautiful and disquieting intimation that truth may be something you can see “only out of the corner of your eye,” Laing writes:

There are sights too beautiful to swallow. They stay on the rim of the eye; it cannot contain them… We talk of drinking in a sight, but what of the excess that cannot be caught? So much goes by unseen… No matter how long I stayed outdoors, there was a world that would remain invisible to me, just at the cusp of perception, glimpsable only in fragments, as when the delphinium at dusk breathes back its unearthly, ultraviolet blue.

And yet the journey itself seems to train in Laing this essential receptivity to beauty — or, rather, to untrain the imperviousness to it that so-called civilization seeds in us, affirming Terry Tempest Williams’s assertion that beauty is our natural inheritance.

A century and a half after Laing’s compatriot Richard Jefferies insisted that “the hours when the mind is absorbed by beauty are the only hours when we really live,”she records one such sublime moment of surrender to beauty on the meadowy banks of the Ouse not far from the English Channel:

What a multitude of mirrors there are in the world! Each blade of grass seemed to catch the sun and toss it back to the sky.

[…]The wheat was preoccupying me. It had here reached another stage, the long greenish hairs unfurling and turning it into an ocean of grass, in which the wind moved as it will across water, folding the pile first back, now forth. The wind worked across it and so did the light, and I could not at first piece together how the trick was mastered. The stalks here, on this sloped field, were almost blue, a blue that increased from the boot upward like a flush, though later in the month they would grow gilded and then bleach daily until they were almost drained of colour, becoming the common straw that was once used to roof most of England and is still required by law for repairing the thatch of some listed buildings. The heads of the wheat were golden; the hairs that are known as the beard a watery greenish gold that became bronze towards the tip. When the wind flattened the heads — ah, that was it! — they caught the light, which rippled and rushed down the hill in little ebbs and flurries.

And yet, even as these internal transformations come abloom, Laing carries with her and continually revisits the heartache that set her off on the journey. In one of those cyclical thrusts into bleakness that are the hallmark of every grief, she writes:

It began to occur to me that the whole story of love might be nothing more than a wicked lie; that simply sleeping beside another body night after night gives no express right of entry to the interior world of their thoughts or dreams; that we are separate in the end whatever contrary illusions we may cherish; and that this miserable truth might as well be faced, since it will be dinned into one, like it or not, by the attritions of time if not by the failings of those we hold dear… It would be a long time before I trusted someone, for I’d seen how essentially unknowable even the best loved might prove to be.

Still, the most remarkable aspect of the human heart may be just how elastic our range of experience is — how, even at its most contracted by loss and turmoil, the heart can be seized with delight and surprised by visitations of acute joy. Laing is swallowed by one such moment when, delirious and almost euphoric with hunger and fatigue, she finally reaches the Ouse’s homecoming to the sea:

What a bay! What a day! I turned full circle, treading water, liking the way the land seemed to hold out two chalky arms to fend off or embrace the waves. I could see all the way to Seaford Head in the east, and in the west there were the two lighthouses that marked the mouth of the Ouse, gushing out into the Channel at a thousand tonnes a minute. There must have been the odd molecule drifting in these crashing waters that had travelled south beside me, working its way from the oak-shadowed source down the deep gulleys of Sheffield Park, across the gravel beds of Sharpsbridge, over the fish ladders at Barcombe Mills, past the wharves of Lewes and out through the maze-ways of the Brooks… I kicked out my legs and wallowed there in joy.

This cyclical interplay of joy and despair parallels the fate of the physical world. Beholding a dry riverbed where the Ouse meets the sea — the remains of Tide Mills Creek — Laing draws on her riverine journey to contemplate the largest questions of existence and its counterpoint:

It’s a mercy that time runs in one direction only, that we see the past but darkly and the future not at all. But we all have an inkling of what lies ahead, for against the ruins of the ages it is apparent that our time is nothing more than the passing of a shadow and that our lives… run like sparks through the stubble.

The tenacity of our physical remains, their unwillingness to fully disappear, is at odds with whatever spark provides our animation, for the whereabouts of that after death is a mystery yet to be unpicked. What is this world, really? We’re told we have infinite choice and yet there’s so much that occurs beyond the perimeters of our command. We do not know why we’re set down here and though we may choose the moment when we leave, not a single one of us can shift the position we’ve been assigned in time, nor bring back those we love once they have ceased to breathe.

Illustration from Cry, Heart, But Never Break, a Danish meditation on love and loss

In a sentiment evocative of poet Jane Hirshfield’s ode to the raw optimism of the natural world, Laing adds as she stands at the seashore where the Ouse ends:

These sound like cheerless thoughts, but they filled me with a strange exhilaration… Down in the riverbed, in this territory of vanishings, I might have been at loose in any time. The things that survived here did so against all odds, blooming into the teeth of the wind, amid the shifting beds of shingle. The plants rose from the stones like a conjurer’s trick, working roots down into hidden pockets of sabulous soil: white and gold stonecrops with their flowers like stars; the spiked leaves and overblown petals of yellow horned poppy; great outcrops of sea kelp, the leaves whittled into extraordinary shapes by the relentless churnings of the air… [I was] as purely happy as I’ve ever been right then, in that open passageway beneath the blue vault of sky, walking the measure allotted me, with winter on each side… I had the sense I’d fallen into some other world, adjacent to our own, and though I would at any moment be pitched back, I thought I might have grasped the knack of slipping to and fro.

It is not an accident but some elemental part of our humanity that the sea should catalyze such existential revelations at the borderline of the tragic and the transcendent. “Against this cosmic background,” Rachel Carson wrote when she invited the human imagination into the life of the sea decades before Laing walked the Ouse and shortly before Virginia Woolf drowned in it, “the lifespan of a particular plant or animal appears, not as drama complete in itself, but only as a brief interlude in a panorama of endless change.”

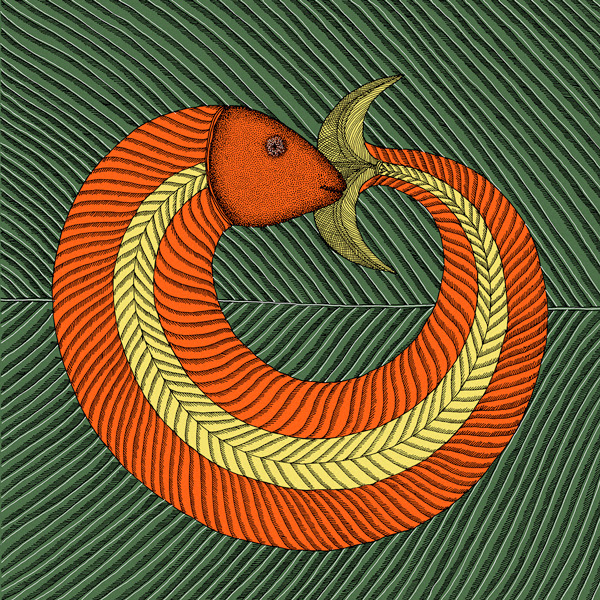

“Death and Rebirth” by artist Bhajju Shyam from Creation, an illustrated cosmogony based on Indian folklore mythology.

At this shoreside endpoint of her journey, Laing offers a poetic denouement:

Outside the Downs had disappeared, obliterated by a swelling wall of thunderheads. The cloud was growing as I watched, banking up into headwalls and cornices and deep ice-blue gullies. It looked like the aftermath of an explosion, like the world beyond the hills had been bombed to smithereens. But that’s how we go, is it not, between nothing and nothing, along this strip of life, where the ragworts nod in the repeating breeze? Like a little strip of pavement above an abyss, Virginia Woolf once said. And if she’s right, then the only home we’ll ever have is here. This is it, this spoiled earth. We crossed the river then and pulled away, and in the empty fields the lark still spilled its praise.

To the River is an immensely beautiful read in its entirety. Complement it with Laing’s subsequent existential experiment in the art of being alone, then revisit Virginia Woolf on the shock-receiving capacity necessary for being an artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment