Musicked Down the Mountain: How Oliver Sacks Saved His Own Life by Literature and Song

by Maria Popova

The extraordinary survival story of “a creature of muscle, motion and music, all inseparable and in unison with each other.”

“Without music I should wish to die,” the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote in a 1920 letter to a friend. One fateful afternoon half a century later, beloved British neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks (b. July 9, 1933) — a Millay of the mind, a lover of poetry, and a scientist of enormous spiritual exuberance — came to live this sentiment as more than a dramatic hyperbole.

“Without music I should wish to die,” the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote in a 1920 letter to a friend. One fateful afternoon half a century later, beloved British neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks (b. July 9, 1933) — a Millay of the mind, a lover of poetry, and a scientist of enormous spiritual exuberance — came to live this sentiment as more than a dramatic hyperbole.

In his superb 1984 memoir A Leg to Stand On(public library), Dr. Sacks tells the story of an extraordinary experience he had atop a Norwegian mountain a decade earlier, on “an afternoon of peculiar splendor, earth and air conspiring in beauty, radiant, tranquil, suffused in serenity,” many miles from the nearest human being — an experience in which the only thing that stood between him and his death was music; an experience that brought him not merely near death but in an intimate tango with it danced to the sound of life itself.

With his Thoreauesque prose, Dr. Sacks recounts the August day on which he set out to climb a Norwegian fjørd up a steep mountain path and before descending into hell:

Saturday the 24th started overcast and sullen, but there was promise of fine weather later in the day… I looked forward to the walk with assurance and pleasure.I soon got into my stride — a supple swinging stride, which covers ground fast. I had started before dawn, and by half past seven had ascended, perhaps, to 2,000 feet. Already the early mists were beginning to clear. Now came a dark and piney wood, where the going was slower, partly because of knotted roots in the path and partly because I was enchanted by the world of tiny vegetation which sheltered in the wood, and was always stopping to examine a new fern, a moss, a lichen. Even so, I was through the woods by a little after nine, and had come to the great cone which formed the mountain proper and towered above the fjørd to 6,000 feet.

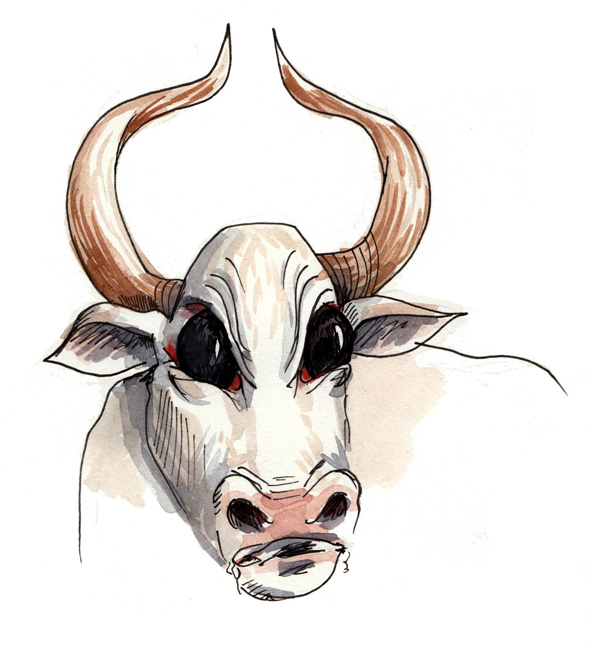

There, to his surprise, was a fence bearing an even more surprising sign: “BEWARE OF THE BULL!” Accompanying the cautionary verbal message was a visual one in the universal language of comic art: “a rather droll picture of a man being tossed.”

So absurd was the sign, so bizarre the very notion of a dangerous bull living up in the fjørd, that Dr. Sacks took it for a prank by the local villagers and carried on, walking past the fence and up the path, determined to make it to the top of the mountain by noon. Unperturbed by the awareness of this “not exactly a populous part of the world,” he felt rather liberated by the sense of solitude — the kind of soul-stretching solitude where, as Wendell Berry memorably put it, “one’s inner voices become audible.”

And, suddenly, his solitude was ruptured by a most prominent presence:

There were ambiguous moments when I would stop in uncertainty, while I descried the shrouded shapes before me. … But when it happened, it was not at all ambiguous!The real Reality was not such a moment, not touched in the least by ambiguity or illusion. I had, indeed, just emerged from the mist, and was walking round a boulder as big as a house, the path curving round it so that I could not see ahead, and it was this inability to see ahead which permitted the Meeting. I practically trod on what lay before me — an enormous animal sitting in the path, and indeed totally occupying the path, whose presence had been hidden by the rounded bulk of the rock. It had a huge horned head, a stupendous white body and an enormous mild milk-white face. It sat unmoved by my appearance, exceedingly calm, except that it turned its vast white face up towards me. And in that moment, in my terror, it changed, before my eyes, becoming transformed from magnificent to utterly monstrous. The huge white face seemed to swell and swell, and the great bulbous eyes became radiant with malignance. The face grew huger and huger all the time, until I thought it would blot out the universe. The bull became hideous — hideous beyond belief, hideous in strength, malevolence and cunning. It seemed now to be stamped with the infernal in every feature. It became, first a monster, and now the Devil.

Mustering a semblance of composure, Dr. Sacks spun on his heel mid-stride, turned around, and coolly began his descent. But the calm facade soon gave way to the irrepressible inner terror of the encounter:

I ran for dear life — ran madly, blindly, down the steep, muddy, slippery path, lost here and there in patches of mist. Blind, mad panic! — there is nothing worse in the world — nothing worse, and nothing more dangerous. I cannot say exactly what happened. In my plunging flight down the treacherous path I must have mis-stepped — stepped on to a loose rock, or into mid-air. It is as if there is a moment missing from my memory — there is “before” and “after,” but no “in-between.” One moment I was running like a madman, conscious of heavy panting and heavy thudding footsteps, unsure whether they came from the bull or from me, and the next I was lying at the bottom of a short sharp cliff of rock, with my left leg twisted grotesquely beneath me, and in my knee such a pain as I had never, ever known.

Always a master of extrapolating from the facts of his life the greater truths of human existence, he adds:

To be full of strength and vigor one moment and virtually helpless the next, in the pink and pride of health one moment and a cripple the next, with all one’s powers and faculties one moment and without them the next — such a change, such suddenness, is difficult to comprehend, and the mind casts about for explanations.

True to our tendency to leave our bodies after trauma, Dr. Sacks found himself, despite the excruciating pain, an almost disembodied observer of what was happening — but he used this disembodiment to his advantage, recasting his role in the unfolding drama from that of the patient to that of the professional physician. As if performing for an invisible audience of his students, he examined himself to determine the extent of the injury — “a complete rupture of the quadriceps tendon… muscle paralyzed and atonic.. unstable knee-joint… ripped out the cruciate ligaments.. considerable swelling, probably tissue and joint fluid, but tearing of blood vessels can’t be excluded…” — and proclaimed, aloud into the solitary stillness of the mountain air, that it was “a fascinating case!”

But he soon remembered that he was also the patient, the “case” in question:

Now, all of a sudden, the fearful sense of my aloneness rushed in upon me.

He realized, too, that at this altitude and latitude, he could easily freeze to death overnight, so his survival depended on being rescued before nightfall. He knew he had to climb down the mountain, closer to the villages, where his chances of being found would be higher.

What happened next was nothing short of astonishing — a supreme feat of the human spirit.

Mobilized by the life-or-death choice before him, Dr. Sacks found himself suddenly “very calm and composed.” Thanks to his personal quirk of carrying an umbrella at all times, he had used one as a walking stick up the mountain and had somehow clutched it by instinct during his fall. Ripping his anorak in two and snapping off the umbrella handle, he fashioned a makeshift splint for his limp leg — without one, he realized, he wouldn’t have been able to move.

Speaking to a truth we all too often forget or gloss over — the fact that “luck” is a contextual grace, relative rather than absolute — Dr. Sacks adds:

Mercifully, then, I had not torn an artery, or major vessel, internally… I had not fractured my spine or my skull in my fall. I had three good limbs, and the energy and strength to put up a good fight. And, by God, I would! This would be the fight of my life — the fight of one’s life which is the fight forlife.

What followed is a remarkable testament to how great art lodges itself in the soul, a Trojan horse of hope, installing in us a kind of dormant software of knowledge and resourcefulness activated in moments of acute need — like the need to fight for one’s life. As Neil Gaiman observed in his magnificent meditation on how stories last, great art “can furnish you with armor, with knowledge, with weapons, with tools you can take back into your life to help make it better.” That’s precisely what Dr. Sacks experienced as he realized that if he didn’t make it off the mountain by nightfall, he would likely freeze to death. Suddenly, he remembered Tolstoy’s Master and Man — a moving 1885 short story about a selfish master who undergoes a spiritual awakening as he brings his peasant back from the brink of hypothermia by lying on top of him to save his life. The memory of this story sparked a life-saving epiphany:

If only I had had a companion with me! The thought suddenly came to me once again, in the words from the Bible not read since childhood, and not consciously recollected, or brought to mind, at all: “Two are better than one … for if they fall, the one will lift up his fellow; but woe to him that is alone when he falleth, for he hath not another to help him up.” And, following immediately upon this, came a sudden memory, eidetically clear, of a small animal I had seen in the road, with a broken back, hoisting its paralyzed hindlegs along. Now I felt exactly like that creature. The sense of my humanity as something apart, something above animality and mortality — this too disappeared at that moment, and again the words of Ecclesiastes came to my mind: “For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; as the one dieth, so dieth the other … so that a man hath no pre-eminence above a beast.”

A series of such life-saving literary epiphanies followed, carrying Dr. Sacks’s spirit over the abyss of desperation and connecting once more to his work with patients:

While splinting my leg, and keeping myself busy, I had again “forgotten” that death lay in wait. Now, once again, it took the Preacher to remind me. “But,” I cried inside myself, “the instinct of life is strong within me. I want to live — and, with luck, I may still do so. I don’t think it is yet my time to die.” Again the Preacher answered, neutral, non-committal: “To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven. A time to be born, and a time to die; a time …” This strange, profound emotionless clarity, neither cold, nor warm, neither severe nor indulgent, but utterly, beautifully, terribly truthful, I had encountered in others, especially in patients, who were facing death and did not conceal the truth from themselves; I had marvelled, though in a way uncomprehendingly, at the simple ending of Tolstoy’s “Hadji Murad” — how, when Hadji has been fatally shot, “images without feelings” stream through his mind; but now, for the first time, I encountered this — in myself.

With this unfeeling clarity, he came up with the kind of idiosyncratic ingenuity that only grave necessity sparks:

I proceeded, using a mode of travel I had never used before — roughly speaking, gluteal and tripedal. That is to say, I slid down on my backside, heaving or rowing myself with my arms and using my good leg for steering and, when needed for braking, with the splinted, flail leg hanging nervelessly before me. I did not have to think out this unusual, unprecedented, and — one might think — unnatural way of moving. I did it without thinking, and very soon got accustomed to it. And anyone seeing me rowing swiftly and powerfully down the slopes would have said, “Ah, he’s an old hand at it. It’s second nature to him.”

Always extrapolating from the particular to the universal and using his personal experience as raw material for advancing his scientific work to the benefit of all humanity, he adds:

So the legless don’t need to be taught to use crutches: it comes “unthinkingly” and “naturally,” as if the person had been practicing it, in secret, all his life. The organism, the nervous system, has an immense repertoire of “trick movements” and “back-ups” of every kind — completely automatic strategies, which are held “in reserve.” We would have no idea of the resources which exist in potentia, if we did not see them called forth as needed.

In a sentiment that speaks to the same alignment of haste and hopelessness against which Kierkegaard admonished two centuries earlier, Dr. Sacks remarks:

I could not hurry — I could only hope.

At that point, he thought of crying for help, and did — “lustily, with huge yells, which seemed to echo and resound from one peak to another.” But the cries suddenly reawakened his terror of the bull and made him fear a vengeful attack by the beastly overlord of the fjørd. So he descended in perfect silence, too afraid to even whistle, as “the hours passed, silently, slithering.”

Suddenly, he came upon a seemingly insurmountable obstacle — a stream he had been reluctant to cross even on his able-bodied way up, which he now had to traverse somehow. Unable to “row” himself across it with his gluteal-tripedal technique, he flipped into a facedown position and, with rigid outstretched arms — lest we forget, Dr. Sacks had been a weightlifting champion just a few years earlier — he propelled himself across the rapid-flowing, ice-cold stream, his head barely above water, exhorting himself:

Hold on, you fool! Hold on for dear life! I’ll kill you if you let go — and don’t you forget it!

But when he made it to the other shore, he faced another fork in this otherworldly road between life and death, one chillingly familiar to mountaineers and polar adventurers alike:

Somehow my exhaustion became a sort of tiredness, an extraordinarily comfortable, delicious languor.“How nice it is here,” I thought to myself. “Why not a little rest — a nap maybe?”The apparent sound of this soft, insinuating, inner voice suddenly woke me, sobered me and filled me with alarm. It was not “a nice place” to rest and nap. The suggestion was lethal and filled me with horror, but I was lulled by its soft, seductive tones.“No,” I said fiercely to myself. “This is Death speaking — and in its sweetest, deadliest Siren-voice. Don’t listen to it now! Don’t listen to it ever! You’ve got to go on whether you like it or not. You can’t rest here — you can’t rest anywhere. You must find a pace you can keep up, and go on steadily.”This good voice, this “life” voice, braced and resolved me.

Another, life-saving Siren took over — music’s miraculous power to enliven, which he had witnessed in his patients and recorded in his now-legendary book-turned-movie Awakenings, published just a few months before his encounter with the taurine devil. He recounts:

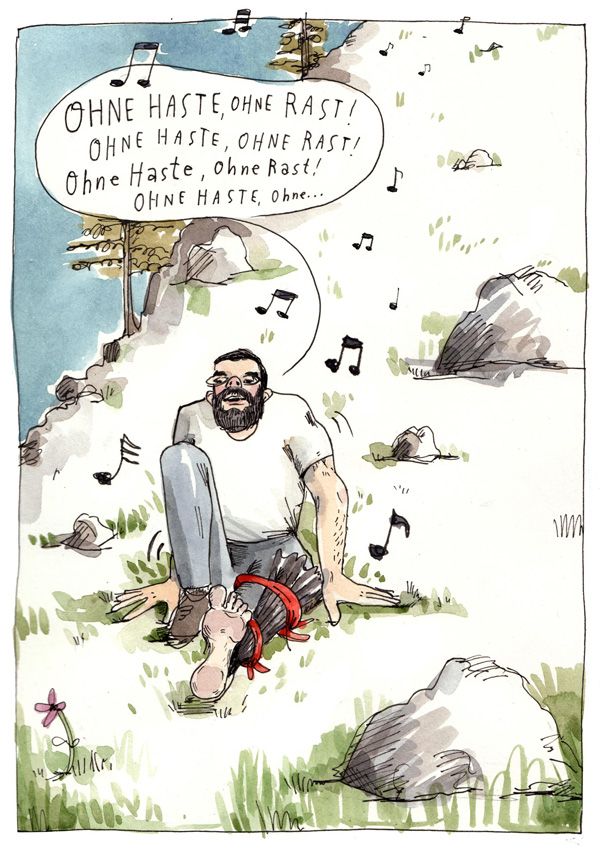

There came to my aid now melody, rhythm and music. Before crossing the stream, I had muscled myself along — moving by main force, with my very strong arms. Now, so to speak, I was musicked along. I did not contrive this. It happened to me. I fell into a rhythm, guided by a sort of marching or rowing song, sometimes the Volga Boatmen’s Song, sometimes a monotonous chant of my own, accompanied by these words “Ohne Haste, ohne Rast! Ohne Haste, ohne Rast!”(“Without haste, without rest”), with a strong heave on everyHaste and Rast. Never had Goethe’s words been put to better use!

Oh, how Goethe, himself an ardent advocate of science, would have rejoiced in knowing that his art was nothing short of life-saving for one of humanity’s greatest scientific minds. This melodic transcendence uncorked a surprising reservoir of perfectly paced strength Dr. Sacks didn’t know he had:

I no longer had to think about going too fast or too slow. I got into the music, got into the swing, and this ensured that my tempo was right. I found myself perfectly co-ordinated by the rhythm — or perhaps subordinated would be a better term: the musical beat was generated within me, and all my muscles responded obediently — all save those in my left leg which seemed silent — or mute? Does not Nietzsche say that when listening to music, we “listen with our muscles?” I was reminded of my rowing days in college, how the eight of us would respond as one man to the beat, a sort of muscle-orchestra conducted by the cox.Somehow, with this “music,” it felt much less like a grim anxious struggle. There was even a certain primitive exuberance, such as Pavlov called “muscular gladness.” And now, further, to gladden me more, the sun burst from behind the clouds, massaged me with warmth and soon dried me off. And with all this, and perhaps other things, I found my internal weather was most happily changed.

More than thirty years later, in his 2007 book Musicophilia, Dr. Sacks would come to illuminate the neurological underpinnings of this astounding connection between music and the mind. But here, one limp foot over the precipice of death atop the Norwegian mountain, he simply observed with awe the way in which music led his mind to mobilize his body into the rhythmic motion that would carry him to survival:

It was only after chanting the song in a resonant and resounding bass for some time that I suddenly realized that I had forgotten the bull. Or, more accurately, I had forgotten my fear — partly seeing that it was no longer appropriate, partly that it had been absurd in the first place. I had no room now for this fear, or for any other fear, because I was filled to the brim with music. And even when it was not literally (audibly) music, there was the music of my muscle-orchestra playing — “the silent music of the body,” in Harvey’s lovely phrase. With this playing, the musicality of my motion, I myself became the music — “You are the music, while the music lasts.” A creature of muscle, motion and music, all inseparable and in unison with each other — except for that unstrung part of me, that poor broken instrument which could not join in and lay motionless and mute without tone or tune.As a child I had once had a violin which got brutally smashed in an accident. I felt for my leg, now, as I felt long ago for that poor broken fiddle. Admixed with my happiness and renewal of spirit, with the quickening music I felt in myself, was a new and sharper and most poignant sense of loss for that broken musical instrument which had once been my leg. When will it recover? I thought to myself. When will it sound its own tune again? When will it rejoin the joyous music of the body?

At last, he could see the village in the distance — close enough to see it but not close enough for his cries for help to be heard, a tortuous rift between possibility and impossibility that once again reminded him of the interconnectedness of all life:

An anguish of yearning sharpened my eyes, a violent need to see my fellow men and, even more, to be seen by them. Never had they seemed dearer, or more remote… There was something impersonal, or universal, in my feeling. I would not have cried “Save me, Oliver Sacks!” but “Save this hurt living creature! Save life!,” the mute plea I know so well from my patients — the plea of all life facing the abyss, if it be strongly, vividly, rightly alive.

Slowly losing hope that he would live to see another tomorrow, his mind began unraveling the yarn of yesterdays of which a life is woven:

As the blue and golden hours passed, I continued steadily on my downward trek, which had become so smooth, so void of difficulties, that my mind could move free of the ties of the present… Hundreds of memories would pass through my mind, in the space between one boulder and the next, and yet each was rich, simple, ample, complete, and conveyed no sense of being hurried through… Entire scenes were re-lived, entire conversations re-played, without the least abbreviation. The very earliest memories were all of our garden — our big old garden in London, as it used to be before the war. I cried with joy and tears as I saw it — our garden with its dear old iron railings intact, the lawn vast and smooth, just cut and rolled (the huge old roller there in a corner); the orange-striped hammock with cushions bigger than myself, in which I loved to roll and swing for hours; and the enormous sunflowers, whose vast inflorescences fascinated me endlessly and showed me at five the Pythagorean mystery of the world…All of these thoughts and images, involuntarily summoned and streaming through my mind, were essentially happy, and essentially grateful. And it was only later that I said to myself “What is this mood?” and realized that it was a preparation for death. “Let your last thinks all be thanks,” as Auden says.

Just as the sun set and dusk began descending with its promise of darkness and death, the improbable happened: Two reindeer hunters, a father and a son, emerged atop a nearby rock as though out of thin air, saw that struggling “creature of muscle, motion and music,” and ran toward him. Dr. Sacks recounts:

I had become almost totally unaware of the environment, having, at some level, given up all thoughts of rescue and life, so that rescue, when it came, came from nowhere, a miracle, a grace, at the very last moment.

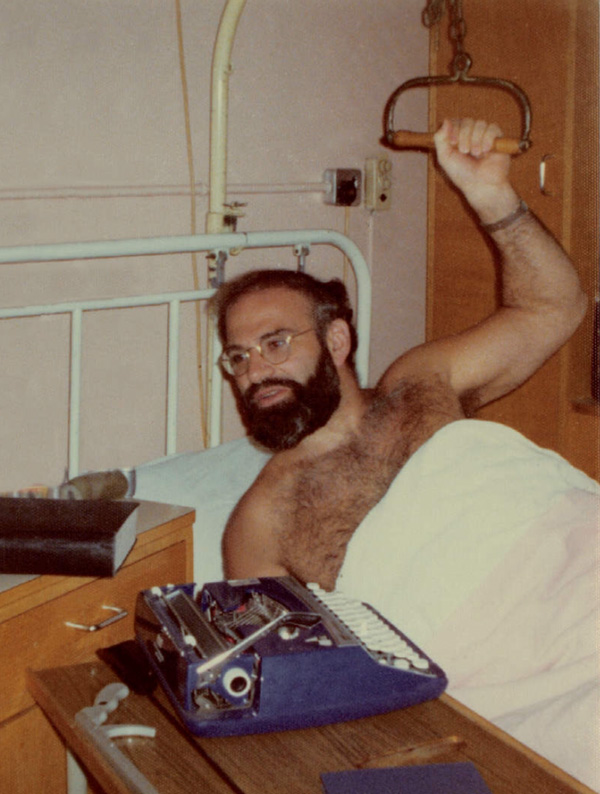

As if this miraculous salvation by literature, music, and human kindness wasn’t already a most remarkable testament to Dr. Sacks’s genius and tenacity of spirit, the story took an even more moving turn as he found himself at the hospital, at once immensely grateful for his life and terrified of the long journey toward an uncertain recovery:

There was to be another story or, perhaps, another act in the same strange complex drama, which I found utterly surprising and unexpected at the time and almost beyond my comprehension or belief.

Bedridden in a small Norwegian hospital, in the so-called care of an uncaring and downright hostile nurse, he found most anguishing of all the complete privation of music. He longed for it “hungrily, thirstily, desperately.” At last, a friend brought him a tape recorder with a single cassette — Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto.

Dr. Sacks recounts the reprise of music’s enlivening role in the story of his survival:

It was (and remains) a matter of amazement to me that this charming, trifling piece of music should have had such a profound and, as it turned out, decisive effect on me. From the moment the tape started, from the first bars of the Concerto, something happened, something of the sort I had been panting and thirsting for, something that I had been seeking more and more frenziedly with each passing day, but which had eluded me. Suddenly, wonderfully, I was moved by the music. The music seemed passionately, wonderfully, quiveringly alive — and conveyed to me a sweet feeling of life. I felt, with the first bars of the music, a hope and an intimation that life would return to my leg — that it would be stirred, and stir, with original movement, and recollect or recreate its forgotten motor melody. I felt, in those first heavenly bars of music, as if the animating and creative principle of the whole world was revealed, that life itself was music, or consubstantial with music; that our living moving flesh, itself, was “solid” music — music made fleshy, substantial, corporeal.[…]The sense of hopelessness, of interminable darkness, lifted… A sense of renewal grew upon me.

In the remainder of A Leg to Stand On — a book as invigorating as Mendelssohn’s concerto — Dr. Sacks goes on to explore the mysterious machinery that carries the human mind and body to recovery after serious injury. Complement it with Dr. Sacks on storytelling and the psychology of writing and his breathtaking autobiography, which remains one of the most rewarding reading experiences of my life.

No comments:

Post a Comment