Jack Lemmon in "The Apartment"

No Vacation Nation

America Is Dead Last

Americans Are More Devoted To Stress Than To The Relaxation Of Vacation

Countries With The Most Vacation Days

The Stark Disparities Of Paid Leave: The Rich Get Healed, The Poor Get Fired

“You were right—I do feel more productive standing.”

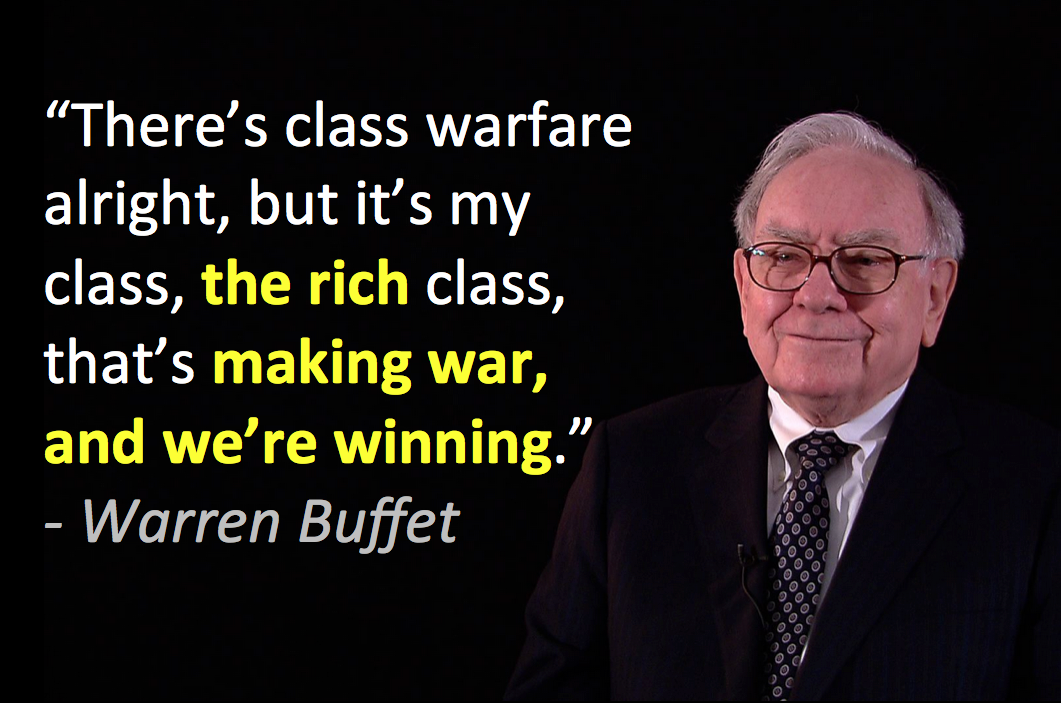

Alan: Our "social contract" is so frayed that American workers have come to adulate their oppressors or at least normalize their oppression.

"Plutocracy Triumphant"

Cartoon Compendium

"Politics And Economics: The 101 Courses You Wish You Had"

"Politics And Economics: The 101 Courses You Wish You Had"

Your

job will never love you: Stress and anxiety in our new job world

The economy has become so insecure that the very workers who should be wary of employers feel forced to defend them. Excerpted from "The Tumbleweed Society: Working and Caring in an Age of Insecurity"

Beth Mendel had had a successful career in design before she quit her job when her husband was relocated to Virginia from New York City, thinking that she would finally have a little time to be a stay-at-home mom with her four children. A tall woman with eyes crinkling in good humor behind horn-rimmed glasses, she sat across from me in a café, pulling her sweater more tightly around her as she narrated the move. They sold their apartment in the city, bought a house down south, and moved all four children into their new schools, with her parents joining them in the move, she recalled. But a few months later, the company called her husband back up north for an ominous meeting at headquarters; they fired him that day.

He had been assigned to Virginia to downsize the operations there, she remembered, but when that job was done, he was too. Her eyes widening in a can-you-believe-it sort of gentle parody of their shock, Beth invited me to picture the scene. “It was like, ‘We think you’re valuable enough to move you down to Virginia,’ and then, ‘Sorry, we got rid of the plant, and now you’re not valuable anymore.’ It was horrible,” she said, recalling that fluctuations in the housing market meant there was no way they could easily return to their old life in New York. “So imagine him, he was definitely the hatchet man,” she told me. “And then he was hatcheted.”

Beth quickly went back to work, and has not stopped in the eight years since, switching careers to become a human resources manager for several different firms over the next decade. Her husband initially succumbed to a depression, and she would come home to find the kitchen dirty and the kids telling her that another day had gone by with Daddy not getting up from the sofa. Slowly, painfully, he regained his equilibrium enough to work, eventually finding his niche again but at much lower pay, as do a quarter of those displaced workers who find new jobs.

In talking about work, it is not that Beth embraces the new insecurity, exactly. She calls what happened to their family “horrible,” and remembers the trauma: “Oh my gosh, it was awful.” But she also tries hard to move on, with little phrases of acceptance dotting her narrative like mental shrugs. “Yeah, but, you know, hindsight’s 20/20,” she said. “There’s always bumps in the road,” and “What are you going to do?” These little phrases serve to keep her expectations about work low, and contain the emotions she allows herself to feel, since job insecurity is just what we can all predict, simply part of the new economy.

On the other hand, Beth maintains high expectations of herself at work, as a core part of her identity. “Well, I’m a—myself, I’m a very loyal employee. I—when I accept a job, I’m—there’s, you know, it’s in my heart, it’s in my gut,” she said, describing situations in which she thought she probably should have left a company earlier than she did. “Yeah, I don’t just go to a job nine to five, and at five o’clock, oh, it’s time, goodbye. No, that’s not me.” Beth identifies with the employer’s needs, even in an environment in which she knows, through bitter personal experience, that this sort of sentiment is unlikely to be reciprocated.

What do employers owe us, and what do we owe our employers? The question goes to the heart of what we think counts as honorable behavior, of our sense of what we can control, and of what we perceive as the place of ethics in paid labor. Contemporary transformations of work have included the erosion of the old social contract, in which employers promised some sort of job security in return for workers’ loyalty and effort. While that bargain was limited in time and its beneficiaries, increases in actual and perceived job insecurity suggest that for many employers, this set of obligations no longer applies. Yet, at the same time, full-time work continues to be a central component of identity for many, and for some populations— women, young adults—its importance has even increased. These opposing trends—the increases in actual and perceived job insecurity, which we might predict would promote less work attachment—and the increased intensity and cultural importance of full-time employment, which we might predict would promote more work attachment—generate a cultural and emotional collision in people’s lives.

With her opposing stances toward work—where she shrugs her shoulders about job insecurity but fervently avows her own dedication as a worker—Beth typifies a central paradox of our times. I call this lopsided calculus of obligation the “one-way honor system.” Of course, some employed in precarious work sounded a different note, in which they were careful to distinguish between their dedication to peak performance, which is one dimension of work commitment, and their intent to remain in a particular job over time; I discuss these high-performance, low-loyalty workers in greater detail in the next chapter. Furthermore, stably employed workers—those public school teachers, firefighters, people employed in small, longstanding family firms, and the like—maintained high expectations for their employers’ constancy, as well as their own.

Most of the rest, however, seemed to accept that insecurity prevails at work and, like Beth, excuse employers for “hatcheting,” even as they maintained high expectations for their own duty and dedication. Ultimately, the one-way honor system generates a set of very real enigmas: Why do people hold themselves to a different standard of loyalty than they expect of their employers? Given the widespread sense that employers have left the terms of the old social contract behind, why are employees still affirming their own dedication? Furthermore, how do people reconcile themselves emotionally to the uneven balance of obligation at work?

What we expect from employers

Most people in insecure work did not think employers owed their workforce very much at all, if anything. “I guess just respect and appreciation,” said Vicky, a white woman with a master’s degree and a household income of more than $500,000. “It would be nice to have job security, but I don’t know if that’s realistic.”

“I just think the employer is the superior, and they’re in control, they’re in charge. And if they decide to fire you, they can,” said Claudia, a married white saleswoman who recently had to declare bankruptcy. “Of course I could leave, but, I mean, I believe that . . . what’s the word, to be submissive to your employer, to obey their rules, I think we owe them—an employee owes their employer that. You know, when you’re working, you should be working.”

“I think they [employers] should definitely be grateful when they have a good employee,” said Lola, a Latina public school teacher who— unusually—survived a recent bout of layoffs, and talked like a precarious worker. Her tone implying that their responsibilities do not extend much further, Lola was the one whose phrase “And [their employees] are owed their paycheck and a certain amount of respect, I would say” we heard in the last chapter.

Here we are not talking about whether or not people are worried about losing their jobs, the standard measure of perceived job insecurity, but instead whether or not they should have to worry about losing their jobs. In essence, we are taking a measure of the good, of what counts as honorable in the definition of our obligations. Obligations can be tricky to decipher, because to some degree they only matter when they are tested, when circumstances are less than ideal. On some level, commitment and loyalty only become salient under stress: What does an employer owe to a highly valued employee who experiences some sort of home calamity? What about when the company is under stress or changes hands?

Phyllis, an African-American single mother recently laid off from a string of low-paying jobs, maintained that even good employees should not get special consideration from employers if they have a family situation or other emergency arise. “I think that employee needs to get a good, strong support system . . . outside of work. Keep it outside. Once you walk in that door, you’re in a different mode,” Phyllis said. “The employer owes absolutely nothing. And then once you get that into the relationship where you’re bringing it to the employer’s attention, it’s going to be all throughout your business. So no, no, leave it out.”

We might predict that those who are not particularly advantaged by the insecure economy—those at the bottom of the skill hierarchy, who would benefit from a system offering protection from the capricious forces of the job market—would be more likely to argue that employers owed some sort of loyalty, security, or dedication to their employees if those workers were experiencing a momentary emergency. Surely this more vulnerable population would feel more sympathy for the employee’s need for accommodation, than for the employer’s need for performance? Yet even most of those with low-skilled or lower-paying jobs seemed to put themselves in the employer’s shoes.

Fiona, who spent more than a decade as a single mother, had held the most jobs of those to whom I spoke (she stopped listing at eleven); several of those job changes had been involuntary. Even valuable employees need to keep up their productivity, she said. “I don’t think an employer owes an employee [who’s] not doing their job well anything.”

What we expect from employees

If employers owe little beyond respect, dignity, and pay, what do employees owe? According to most—even the stably employed—workers must give their all. Three-quarters of the people I spoke to talked about themselves as “workaholics,” “passionate,” with a “really overdrive work ethic.” Sometimes it felt like there was an ongoing arms race in the percentages people assigned to their own effort, with tales of giving “100 percent,” “110 percent,” “150 percent,” or even “200 percent” on the job. “When I work at a job, I work it as if it’s my own company,” said Nicki, an African-American woman with extensive caregiving obligations who had been laid off. “Their best interest is my best interest. Doing the best that I can to make sure that that company survives.” “My father, you know, ‘Work first, play second’ is how I was raised,” said Marin, who works for her husband’s company. “And [if] you’re due at work at eight, you’d better be there by 7:45, because if you’re not there by 7:45, you may as well not show up. So work has always been very important to me.” Marin’s words capture an aspect that is widely shared here—her relationship to work is personal, as a reflection of her character, of her identity, much as Beth attested.

No comments:

Post a Comment