The Transformation Of Human Life By Lenses

Without eyeglasses, most scholars work would end in their forties.

Without eyeglasses, most scholars work would end in their forties.

"A Brief History Of Optics And Lenses"

http://www.museumofvision.org/exhibitions/?key=44&subkey=4&relkey=29

Alan: My Dad, William Wellington Archibald, was an optical engineer at Eastman Kodak Company

Alan: My Dad, William Wellington Archibald, was an optical engineer at Eastman Kodak Company

The Rebellious and Revolutionary Life of Galileo, Illustrated

by Maria Popova

How a college dropout reordered the heavens and forever changed our understanding of our place in the universe.

In 1564, Galileo Galilei was born into a world with no clocks, telescopes, or microscopes — a world that was believed to be the center of the universe, orbited by the sun and the moon and the stars. By the time he died seventy-seven years later, his ideas had planted the seed for the most significant scientific revolution in human history. In addition to his most notorious astronomical discoveries, which challenged centuries of religious dogma by dethroning Earth as the center of the universe andnearly cost him his life, Galileo alsoinvented modern timekeeping, created the microscope, inspired Shakespeare, and even provided a metaphorical model for understanding how culture evolves.

In 1564, Galileo Galilei was born into a world with no clocks, telescopes, or microscopes — a world that was believed to be the center of the universe, orbited by the sun and the moon and the stars. By the time he died seventy-seven years later, his ideas had planted the seed for the most significant scientific revolution in human history. In addition to his most notorious astronomical discoveries, which challenged centuries of religious dogma by dethroning Earth as the center of the universe andnearly cost him his life, Galileo alsoinvented modern timekeeping, created the microscope, inspired Shakespeare, and even provided a metaphorical model for understanding how culture evolves.

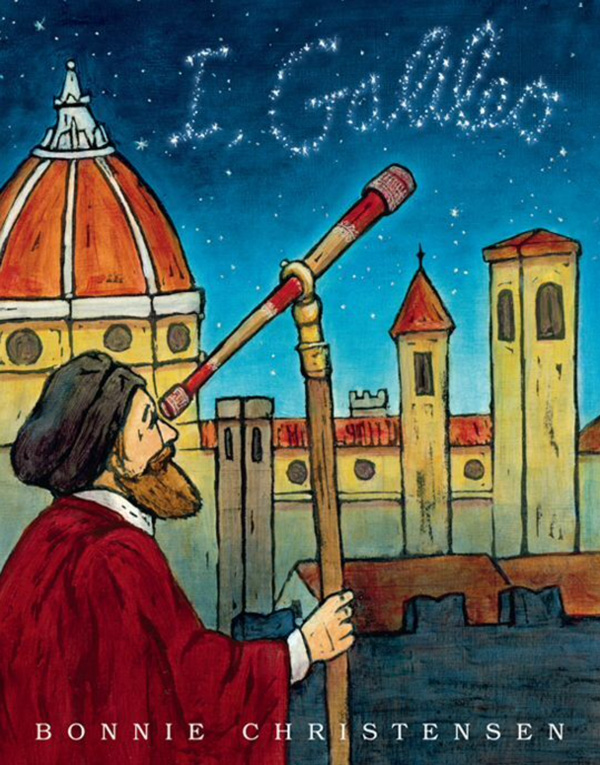

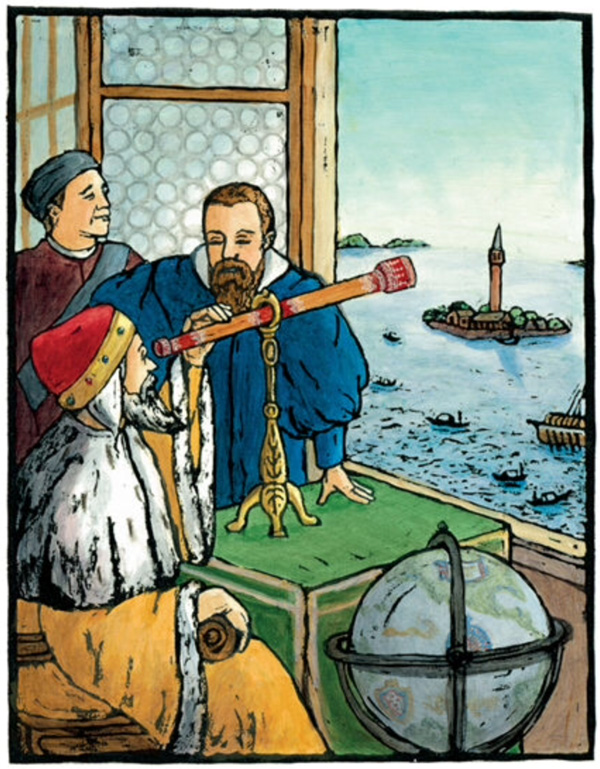

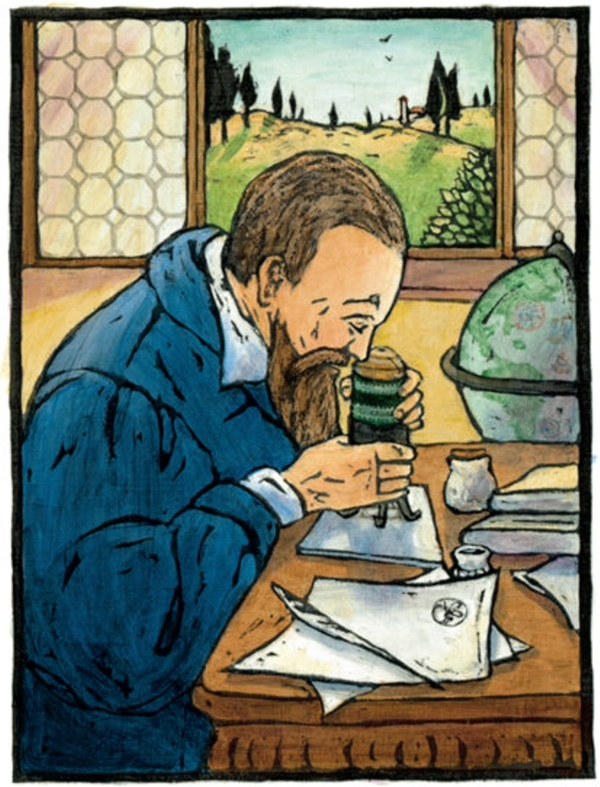

In I, Galileo (public library), writer and artist Bonnie Christensen — who also gave us the marvelous illustrated story of Nellie Bly — chronicles the life of the great Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, and philosopher, adding to both the finest picture-book biographies of cultural icons and the best children’s books celebrating science.

The story, quite possibly inspired by Ralph Steadman’s superb I, Leonardo, is told as a first-person autobiography narrated by Galileo himself. Christensen’s beautiful illustrations pay homage to the aesthetic sensibility of Galileo’s era, partway between the stained glass of European cathedrals and the artistic style of the Old Masters.

We meet Galileo as a blind old man, sentenced to lifelong house arrest by the Inquisition for his dogma-defying discoveries, then travel with him back in time.

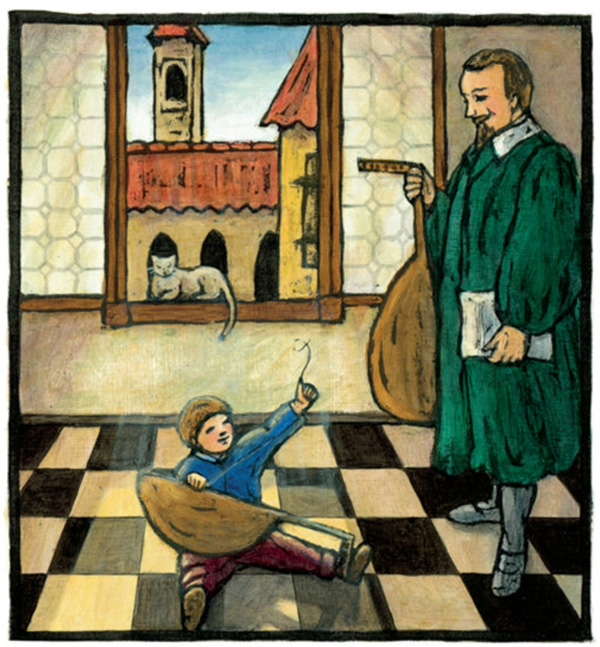

In childhood, his father’s revolutionary theories bridging music and mathematics instilled in the young boy an ethos of challenging convention; at eleven, he was sent to a monastery for his formal education and decided to become a monk, which alarmed his father into sending him to medical school instead; in late adolescence, he dropped out of medical school without a degree.

For the remainder of his adolescence, Galileo was essentially homeschooled and self-taught, conducting various fascinating experiments with his father — such as manipulating the length, tension, and thickness of a string to produce notes of a different pitch.

But his voracious scientific curiosity came at a cost — by twenty-five, Galileo was already quite unpopular for doing away with tradition, from refusing to wear the professorial robes his peers wore to challenging Aristotle’s sacred laws of physics.

Aristotle, the famous ancient Greek philosopher, claimed a heavy object would fall faster than a light objet. I disagreed. To prove my point, I dropped two cannonballs of different weights from the leaning tower. Just as I predicted, they fell at the exact same rate of speed. But the public was not convinced, even in the face of scientific proof. I was not invited to continue teaching at the University of Pisa.

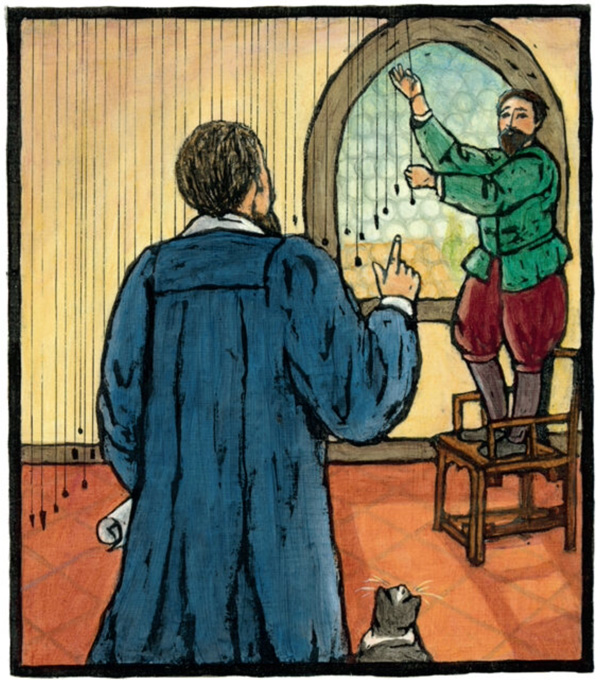

And yet Galileo persevered, continuing to challenge the dogmas of ancient science and religion. His seminal pendulum insight sparked modern timekeeping and his famous telescopic observations, an attraction for Italian royalty, proved that Sun, not the Earth, was what the heavenly bodies orbited.

Aware of how radical and possibly dangerous his discovery was, Galileo remained silent for seven years, during which he inverted the direction of his curiosity and used his lens-making skills to invent the microscope.

When he eventually published his findings, he did indeed incur the wrath of the Inquisition and was locked away in the hills of Arcetri, where he died a blind old man having seen the truth of the universe. His ideas lived on to usher in a whole new era of science and culture, forever changing our relationship to the cosmos and to ourselves.

Complement Christensen’s I, Galileo with the illustrated story of pioneering Persian astronomer and polymath Ibn Sina, then revisit the picture-book biographies of other trailblazing shapers of culture: Jane Goodall, Pablo Neruda, Frida Kahlo, e.e. cummings, and Albert Einstein.

No comments:

Post a Comment