The Spirit Of Sauntering: Wandering In The Holy Land. Henry David Thoreau

Art and the Mind’s Eye: How Drawing Trains You to See the World More Clearly and to Live with a Deeper Sense of Presence

by Maria Popova

A passionate case for learning “to search into the cause of beauty, and penetrate the minutest parts of loveliness.”

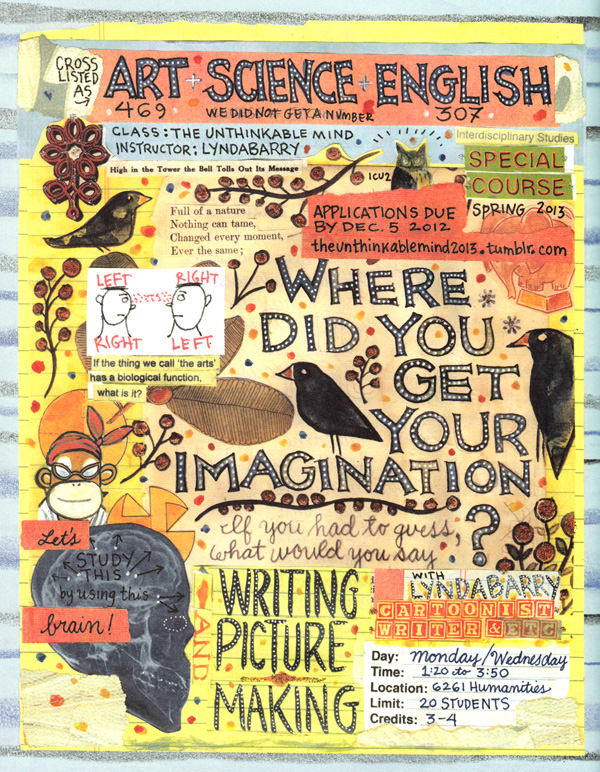

“It’s only when we look with eyes of love that we see as the painter sees,” Henry Miller wrote in his forgotten 1968 gem To Paint Is to Love Again. Drawing, indeed, transforms the secret passageway between the eye and the heart into a two-way street — while we are wired to miss the vast majority of what goes on around us, learning to draw rewires us to see the world differently, to love it more intimately by attending to and coming to cherish its previously invisible details. This, perhaps, is why beloved artist Lynda Barry teaches visual storytelling as the infinitely rewarding art of “being present and seeing what’s there.”

“It’s only when we look with eyes of love that we see as the painter sees,” Henry Miller wrote in his forgotten 1968 gem To Paint Is to Love Again. Drawing, indeed, transforms the secret passageway between the eye and the heart into a two-way street — while we are wired to miss the vast majority of what goes on around us, learning to draw rewires us to see the world differently, to love it more intimately by attending to and coming to cherish its previously invisible details. This, perhaps, is why beloved artist Lynda Barry teaches visual storytelling as the infinitely rewarding art of “being present and seeing what’s there.”

More than a century before Miller and a century and a half before Barry, the great Victorian art critic, philosopher, and philanthropist John Ruskin(February 8, 1819–January 20, 1900) examined the psychology of why drawing helps us see the world more richly in a fantastic piece unambiguously titled Essay on the Relative Dignity of the Studies of Painting and Music, and the Advantages to be Derived from Their Pursuit, penned when he was only nineteen. It is included in the first volume of the altogether indispensable The Works of John Ruskin (public library | free ebook).

It’s a beautiful meditation triply timely today, in an age when we — having succumbed to the “aesthetic consumerism” of photography — are likelier to view the world through our camera phones and likelier still to point those at ourselves rather than at nature’s infinite and infinitely overlooked enchantments. To draw today is to reclaim the dignity and private joy of seeing amid a culture obsessed with looking in public.

Ruskin writes:

Let two persons go out for a walk; the one a good sketcher, the other having no taste of the kind. Let them go down a green lane. There will be a great difference in the scene as perceived by the two individuals. The one will see a lane and trees; he will perceive the trees to be green, though he will think nothing about it; he will see that the sun shines, and that it has a cheerful effect, but that the trees make the lane shady and cool; and he will see an old woman in a red cloak; — et voilà tout!But what will the sketcher see? His eye is accustomed to search into the cause of beauty, and penetrate the minutest parts of loveliness. He looks up, and observes how the showery and subdivided sunshine comes sprinkled down among the gleaming leaves overhead, till the air is filled with the emerald light, and the motes dance in the green, glittering lines that shoot down upon the thicker masses of clustered foliage that stand out so bright and beautiful from the dark, retiring shadows of the inner tree, where the white light again comes flashing in from behind, like showers of stars; and here and there a bough is seen emerging from the veil of leaves, of a hundred varied colours, where the old and gnarled wood is covered with the brightness, — the jewel brightness of the emerald moss, or the variegated and fantastic lichens, white and blue, purple and red, all mellowed and mingled into a garment of beauty from the old withered branch. Then come the cavernous trunks, and the twisted roots that grasp with their snake-like coils at the steep bank, whose turfy slope is inlaid with flowers of a thousand dyes, each with his diadem of dew: and down like a visiting angel, looks one ray of golden light, and passes over the glittering turf — kiss, — kiss, — kissing every blossom, until the laughing flowers have lighted up the lips of the grass with one bright and beautiful smile, that is seen far, far away among the shadows of the old trees, like a gleam of summer lightening along the darkness of an evening cloud.Is not this worth seeing? Yet if you are not a sketcher you will pass along the green lane, and when you come home again, have nothing to say or to think about it, but that you went down such and such a lane.

Drawing not only grants us a more intimate presence with the world but also extends an irresistible invitation for storytelling — that old woman in the red cloak, Ruskin argues, would be a mere passing stranger for the non-sketcher but the sketcher’s mind will envelop her in “an immense deal of speculation” as he seeks to place her properly in the context of the landscape, invariably playing out various possible stories of who she is and how she ended up there. This impulse for creative speculation, Ruskin asserts, is at the core of how the artist sees the world differently:

From the most insignificant circumstance, — from a bird on a railing, a wooden bridge over a stream, a broken branch, a child in a pinafore, or a waggoner in a frock, does the artist derive amusement, improvement, and speculation. In everything it is the same; where a common eye sees only a white cloud, the artist observes the exquisite gradations of light and shade, the loveliness of the mingled colours — red, purple, grey, golden, and white; the graceful roundings of form, the shadowy softness of the melted outline, the brightness without lustre, the transparency without faintness, and the beautiful mildness of the deep heaven that looks out among the snowy cloud with its soft blue eyes; — in fact, the enjoyment of the sketcher from the contemplation of nature is a thing which to another is almost incomprehensible. If a person who had no taste for drawing were at once to be endowed with both the taste and power, he would feel, on looking out upon nature, almost like a blind man who had just received his sight.

The Works of John Ruskin is a trove of timeless wisdom in its totality. Complement this particular piece with Miller’s wonderful To Paint Is to Love Again and Ruskin on the value of imperfection in creative work. If you’re looking to learn this enormously rewarding way of seeing, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain is by far the best initiation.

Thanks, Rob

No comments:

Post a Comment