How do you like them apples?

Genesis 2:18-25

18-20 God said, “It’s not good for the Man to be alone; I’ll make him a helper, a companion.” So God formed from the dirt of the ground all the animals of the field and all the birds of the air. He brought them to the Man to see what he would name them. Whatever the Man called each living creature, that was its name. The Man named the cattle, named the birds of the air, named the wild animals; but he didn’t find a suitable companion.

21-22 God put the Man into a deep sleep. As he slept he removed one of his ribs and replaced it with flesh. God then used the rib that he had taken from the Man to make Woman and presented her to the Man.

How Naming Confers Dignity Upon Life and Gives Meaning to Existence

by Maria Popova

“Finding the words is another step in learning to see.”

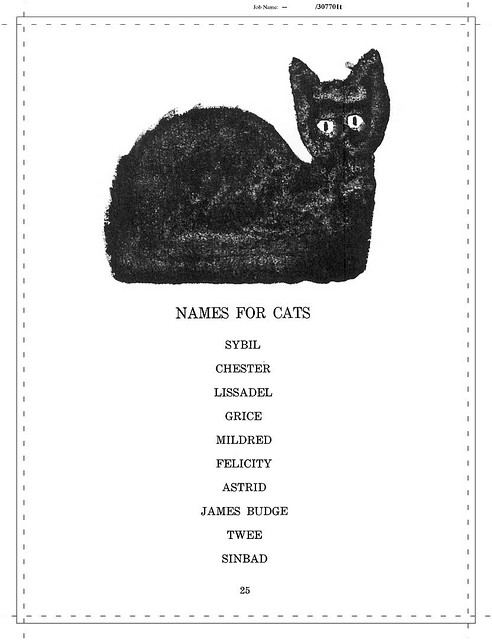

To name a thing is to acknowledge its existence as separate from everything else that has a name; to confer upon it the dignity of autonomy while at the same time affirming its belonging with the rest of the namable world; to transform its strangeness into familiarity, which is the root of empathy. To name is to pay attention; to name is to love. Parents name their babies as a first nonbiological marker of individuality amid the human lot; lovers give each other private nicknames that sanctify their intimacy; it is only when we began naming domesticated animals that they stopped being animals and became pets. (T.S. Eliot made a playful case for the profound potency of this act in “The Naming of Cats.”)

To name a thing is to acknowledge its existence as separate from everything else that has a name; to confer upon it the dignity of autonomy while at the same time affirming its belonging with the rest of the namable world; to transform its strangeness into familiarity, which is the root of empathy. To name is to pay attention; to name is to love. Parents name their babies as a first nonbiological marker of individuality amid the human lot; lovers give each other private nicknames that sanctify their intimacy; it is only when we began naming domesticated animals that they stopped being animals and became pets. (T.S. Eliot made a playful case for the profound potency of this act in “The Naming of Cats.”)

And yet names are words, and words have a way of obscuring or warping the true meanings of their objects. “Words belong to each other,” Virginia Woolf observed in the only surviving recording of her voice, and so they are more accountable to other words than to the often unnamable essences of the things they signify.

Illustration by Ben Shahn from 'Ounce Dice Trice' by poet Alastair Reid, an unusual children's book of imaginative names for ordinary things. Click image for more.

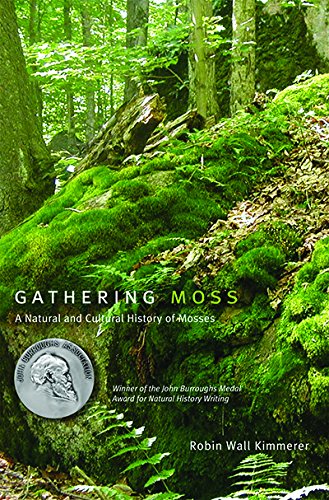

That duality of naming is what Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Thoreau of botany, explores with extraordinary elegance in Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (public library) — her beautiful meditation on the art of attentiveness to life at all scales.

As a scientist who studies the 22,000 known species of moss — so diverse yet so unfamiliar to the general public that most are known solely by their Latin names rather than the colloquial names we have for trees and flowers — Kimmerer sees the power of naming as an intimate mode of knowing. As the progeny of a long lineage of Native American storytellers, she sees the power of naming as a mode of sacramental communion with the world.

Reflecting on a peculiarity of the Adirondack mountains she calls home, where most rocks have been named — “Chair Rock,” “Elephant Rock,” “Burnt Rock” — and people use them as reference points in navigating the land around the lake, Kimmerer writes:

The names we use for rocks and other beings depends on our perspective, whether we are speaking form the inside or the outside of the circle. The name on our lips reveals the knowledge we have of each other, hence the sweet secret names we have for the ones we love. The names we give ourselves are a powerful form of self-determination, of declaring ourselves sovereign territory. Outside the circle, scientific names for mosses may suffice, but inside the circle, what do they call themselves?[…]I find strength and comfort in this physical intimacy with the land, a sense of knowing the names of the rocks and knowing my place in the world.

And yet, echoing Aldous Huxley’s admonition that the trap of language leads us to confuse the words for things with their essences, Kimmerer considers the limiting nature of names from her dual perspective as a scientist and a storyteller:

A gift comes with responsibility. I had no will at all to name the mosses in this place, to assign their Linnean epithets. I think the task given to me is to carry out the message that mosses have their own names. Their way of being in the world cannot be told by data alone. They remind me to remember that there are mysteries for which a measuring ape has no meaning, questions and answers that have no place in the truth about rocks and mosses.

Still, Susan Sontag wrote in contemplating the aesthetics of silence, “human beings are so ‘fallen’ that they must start with the simplest linguistic act: the naming of things.” Naming is an act of redemption and a special form of paying attention, which Kimmerer captures beautifully:

Having words for these forms makes the differences between them so much more obvious. With words at your disposal, you can see more clearly. Finding the words is another step in learning to see.[…]Having words also creates an intimacy with the plant that speaks of careful observation.

What is true of mosses is also true of every element of the world upon which we choose to confer the dignity of recognition. Drawing on her heritage — her family comes from the Bear Clan of the Potawatomi — Kimmerer adds:

In indigenous ways of knowing, all beings are recognized as non-human persons, and all have their own names. It is a sign of respect to call a being by its name, and a sign of disrespect to ignore it. Words and names are the ways we humans build relationships, not only with each other, but also with plants.[…]Intimate connection allows recognition in an all-too-often anonymous world… Intimacy gives us a different way of seeing.

Gathering Moss is one of the most beautifully written books I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. See more of it here, then complement this particular passage with poet and philosopher David Whyte on the deeper meanings of everyday words and a wonderful illustrated catalog of untranslatable words from around the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment