Santa Claus Is More Real Than You Are

***

The Real Story Of Saint Nicholas

who tossed gold through the open windows of poor people

so they didn't sell their daughters into prostitution

***

Margaret Mead on Myth vs. Deception and What to Tell Kids about Santa Claus

by Maria Popova

How to instill an appreciation of the difference between “fact” and “poetic truth,” in kids and grownups alike.

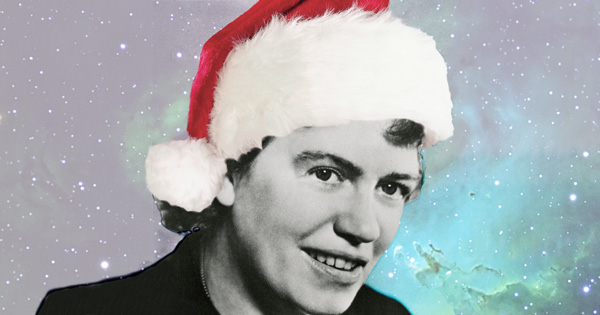

Few things rattle the fine line between the benign magic of mythology and the deliberate delusion of a lie more than the question of how, what, and whether to tell kids about Santa Claus. Half a century ago, Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901–November 15, 1978) — the world’s most influential cultural anthropologist and one of history’s greatest academic celebrities — addressed this delicate subject with great elegance, extending beyond the jolly Christmas character and into larger questions of distinguishing between myth and deception.

Few things rattle the fine line between the benign magic of mythology and the deliberate delusion of a lie more than the question of how, what, and whether to tell kids about Santa Claus. Half a century ago, Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901–November 15, 1978) — the world’s most influential cultural anthropologist and one of history’s greatest academic celebrities — addressed this delicate subject with great elegance, extending beyond the jolly Christmas character and into larger questions of distinguishing between myth and deception.

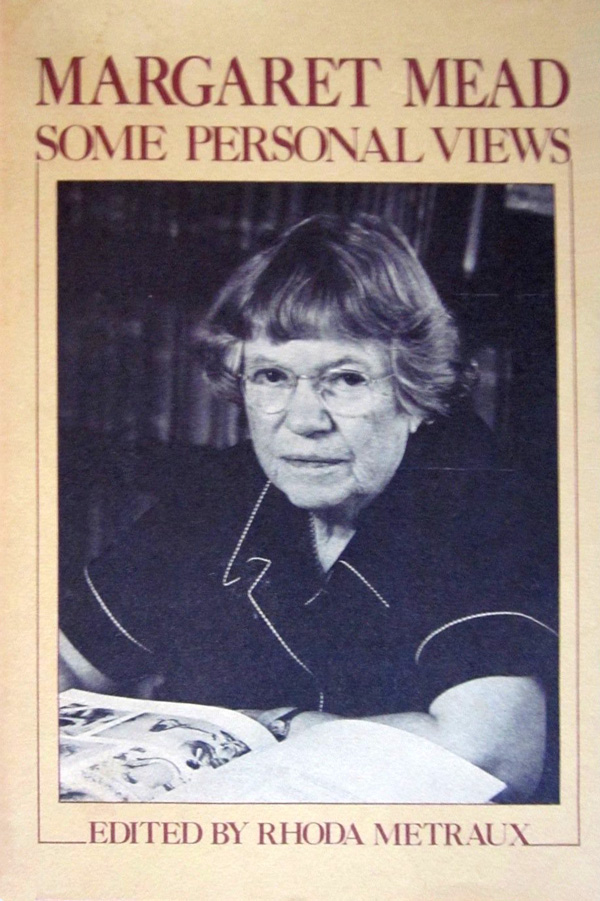

From the wonderful out-of-print volume Margaret Mead: Some Personal Views (public library) — the same compendium of Mead’s answers to audience questions from her long career as a public speaker and lecturer, which also gave us her remarkably timely thoughts on racism and law enforcement and equality in parenting — comes an answer to a question she was asked in December of 1964: “Were your children brought up to believe in Santa Claus? If so, what did you tell them when they discovered he didn’t exist?”

Mead’s response, which calls to mind Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit, is a masterwork of celebrating rational, critical thinking without sacrificing magic to reason:

Belief in Santa Claus becomes a problem mainly when parents simultaneously feel they are telling their children a lie and insist on the literal belief in a jolly little man in a red suit who keeps tabs on them all year, reads their letters and comes down the chimney after landing his sleigh on the roof. Parents who enjoy Santa Claus — who feel that it is more fun talk about what Santa Claus will bring than what Daddy will buy you for Christmas and who speak of Santa Claus in a voice that tells no lie but instead conveys to children something about Christmas itself — can give children a sense of continuity as they discover the sense in which Santa is and is not “real.”

With her great gift for nuance, Mead adds:

Disillusionment about the existence of a mythical and wholly implausible Santa Claus has come to be a synonym for many kinds of disillusionment with what parents have told children about birth and death and sex and the glory of their ancestors. Instead, learning about Santa Claus can help give children a sense of the difference between a “fact” — something you can take a picture of or make a tape recording of, something all those present can agree exists — and poetic truth, in which man’s feelings about the universe or his fellow men is expressed in a symbol.

Recalling her own experience both as a child and as a parent, Mead offers an inclusive alternative to the narrow Santa Claus myth, inviting parents to use the commercial Western holiday as an opportunity to introduce kids to different folkloric traditions and value systems:

One thing my parents did — and I did for my own child — was to tell stories about the different kinds of Santa Claus figures known in different countries. The story I especially loved was the Russian legend of the little grandmother, the babushka, at whose home the Wise Men stopped on their journey. They invited her to come with them, but she had no gift fit for the Christ child and she stayed behind to prepare it. Later she set out after the Wise Men but she never caught up with them, and so even today she wanders around the world, and each Christmas she stops to leave gifts for sleeping children.

But Mead’s most important, most poetic point affirms the idea that children stories shouldn’t protect kids from the dark:

Children who have been told the truth about birth and death will know, when they hear about Kris Kringle and Santa Claus and Saint Nicholas and the little babushka, that this is a truth of a different kind.

Margaret Mead: Some Personal Views is, sadly, long out of print — but it’s an immeasurable trove of Mead’s wisdom well worth the used-book hunt. Complement it with Mead’s beautiful love letters to her soulmate and the story of how she discovered the meaning of life in a dream.

No comments:

Post a Comment