Jane Austen’s Advice on Writing, in Letters to Her Teenage Niece

by Maria Popova

Epistles on the fine art of “speeding truth into the world.”

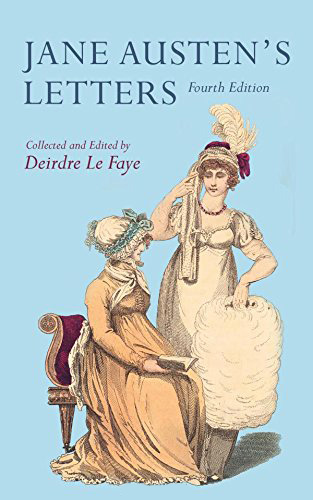

Despite being one of the most important writers our civilization ever produced, on whose labors humanity continues to feed, Jane Austen(December 16, 1775–July 18, 1817) left hardly any record of her opinions and theories on the craft she so masterfully wielded in practice. But a close reading of Jane Austen’s Letters (public library) reveals, here and there, little glimpses of the beloved author’s stylistic convictions — a fine, if modest, addition to this ongoing archive of notable wisdom on writing.

Despite being one of the most important writers our civilization ever produced, on whose labors humanity continues to feed, Jane Austen(December 16, 1775–July 18, 1817) left hardly any record of her opinions and theories on the craft she so masterfully wielded in practice. But a close reading of Jane Austen’s Letters (public library) reveals, here and there, little glimpses of the beloved author’s stylistic convictions — a fine, if modest, addition to this ongoing archive of notable wisdom on writing.

In one 1808 letter to her sister Cassandra, 33-year-old Austen admires a short piece by the English cricketer William Deedes, a friend of Cassandra’s — a glimpse of what she believes makes a good writer:

He has certainly great merit as a writer; he does ample justice to his subject, and without being diffuse is clear and correct… He certainly has a very pleasing way of winding up a whole, and speeding truth into the world.

In another letter from February of 1813, Austen recounts an atypically disappointing work by the English novelist, diarist, and playwright Frances “Fanny” Burney — whose writing Austen generally enjoyed and admired, and whose 1782 novel Cecilia heavily influenced the final pages of Pride and Prejudice— and offers a critique of its shortcomings:

The work is rather too light and bright and sparkling: it wants shade; it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story… something that would form a contrast, and bring the reader with increased delight to the playfulness and epigrammatism of the general style.

But her most explicit counsel on writing comes from a series of letters to her teenage niece, Anna. In August of 1814, 17-year-old Anna asked Austen for feedback on the novel she was writing, under the working title Which Is the Heroine — a title Austen liked “very well” and anticipated to “grow to like it very much in time.” Upon receiving the initial manuscript, Austen writes:

My dear Anna,—I am very much obliged to you for sending your MS. It has entertained me extremely; indeed all of us. I read it aloud to your grandmamma and Aunt Cass, and we were all very much pleased. The spirit does not droop at all.

Austen proceeds to comment on each of Anna’s characters and offers the first of a series of concretely rooted, generally extensible criticisms:

I do not like a lover speaking in the 3rd person; it is too much like the part of Lord Overtley, and I think it not natural.

In the same letter, Austen offers a warm disclaimer to her criticism — “If you think differently, however, you need not mind me.” — but a month later, having immersed herself in the book more thoroughly, she takes off the auntly hat and dons the writerly one. She readies Anna for some tough love:

Anna,—We have been very much amused by your three books, but I have a good many criticisms to make, more than you will like.

After complimenting a number of the girl’s characters and offering her take on the ideal length of a novel — roughly six times Anna’s first section of the novel, or a total of 288 pages — Austen makes a case against the abuses of clichéd phrases:

I have only taken the liberty of expunging one phrase of his which would not be allowable,—”Bless my heart!” It is too familiar and inelegant.

Though herself a master of detail, Austen cautions against overly precious particularities:

You describe a sweet place, but your descriptions are often more minute than will be liked. You give too many particulars of right hand and left.

She encourages the girl to focus on the relationships between the characters against a well-crafted backdrop of place:

You are now collecting your people delightfully, getting them exactly into such a spot as is the delight of my life. Three or four families in a country village is the very thing to work on, and I hope you will do a great deal more, and make full use of them while they are so very favorably arranged.

Toward the end of the letter, Austen makes a remark at first blush amusing in the context of today’s thriving young-adult genre, then rather sad coming from a woman revolutionizing literature from within the patriarchy, and finally reluctantly sage given the general fate of female characters in canon of literature:

You are but now coming to the heart and beauty of your story. Until the heroine grows up the fun must be imperfect… One does not care for girls until they are grown up.

Although one never sees Anna’s letters to Austen — Cassandra had many of her sister’s letters destroyed after her death — it seems like the shaky confidence of the aspiring writer was rattled rather vigorously, for her aunt sent the following assurance a few months later:

My dear Anna,—I have been very far from finding your book an evil, I assure you. I read it immediately and with great pleasure.

Anna never finished her novel. But when Austen died less than three years later, the young woman inherited her aunt’s unfinished manuscript of Sanditon and later became the first writer to attempt completing it. In 1869, she collaborated with her half-brother, James Edward Austen-Leigh, on A Memoir of Jane Austen— the first major biography of their famous aunt and the primary one for decades after its publication, eclipsed only by Jan Fergus’s 1991 biography Jane Austen: A Literary Life.

Couple Jane Austen’s Letters with this year’s finest biographies, memoirs, and history books.

No comments:

Post a Comment