For liberals, one of the few bright spots of this week's election was the resounding defeat of two so-called "personhood" ballot initiatives, which would have extended constitutional rights to embryos.

As ThinkProgress's Tara Culp-Ressler explained:

In Colorado, Amendment 67—which sought to update the state’s criminal code to define fetuses as children—failed by a large 64 percent to 36 percent margin. It marks the third time that Colorado voters have rejected personhood.

Meanwhile, in North Dakota, an effort to overhaul the state’s constitution to protect “the inalienable right to life of every human being at any stage of development” looked like it was poised to pass. Personhood proponents were hopeful that the conservative state would hand them their first major victory, galvanizing the push for similarly restrictive laws in other states. But Amendment 1 was defeated by similarly wide margins as the initiative in Colorado.

This is a familiar story by now. In 2011, voters in ultra-red Mississippi faced a personhood measure which would have virtually outlawed all abortions—and rejected it with an overwhelming majority. In all, the pro-life movement has pushed for such "personhood" bills five times since 2008, and all five have failed.

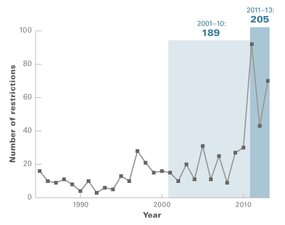

This trouncing might seem unusual given the overall winning streak anti-abortion activists have been on. Between 2011 and 2013, states passed more abortion restrictions than in the three previous decades combined, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

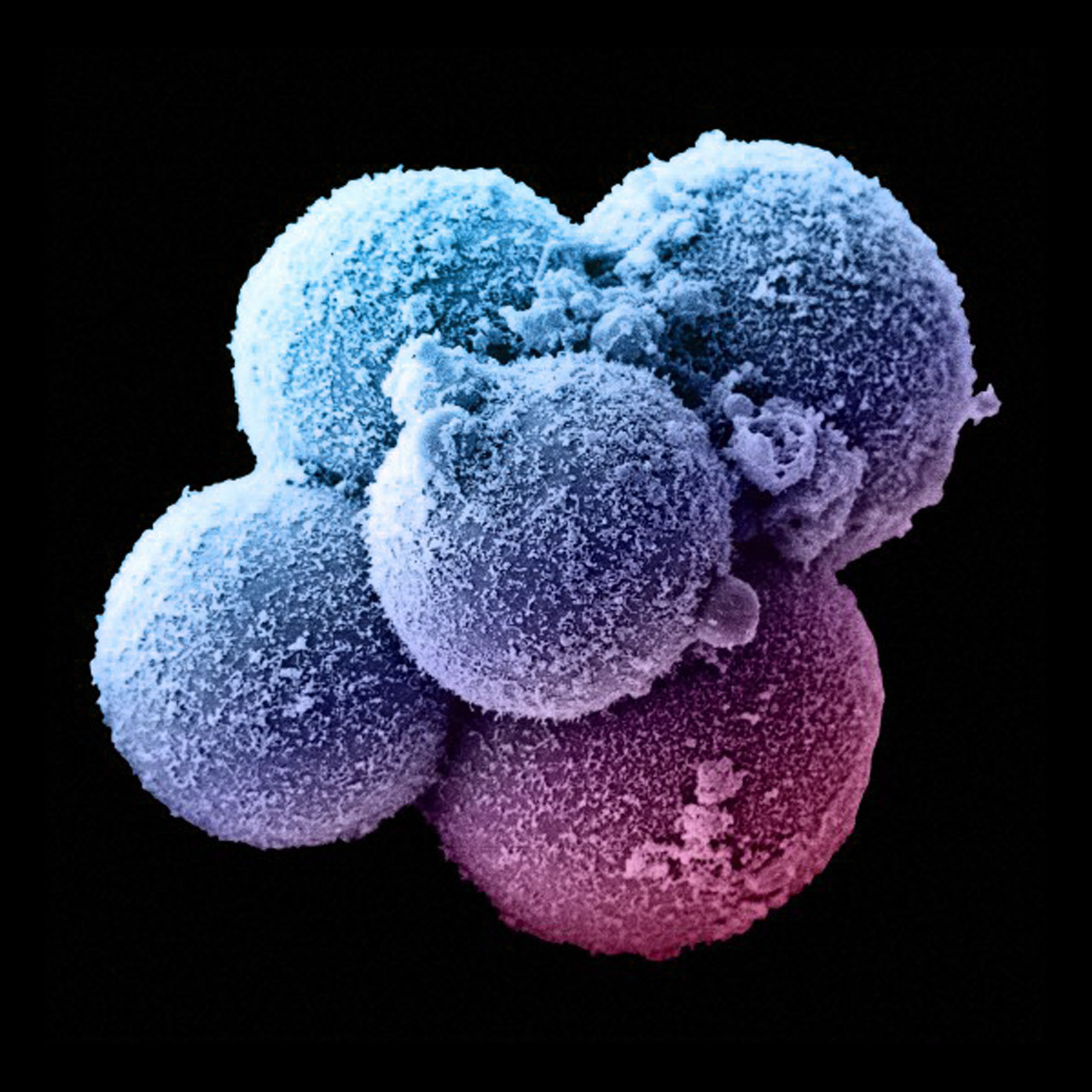

Human Zygote

Most people do not believe that the zygote pictured above is a "human person."

Those who do believe it is a "human person" do so from religious conviction,

not from common sense informed by Reason.

"Abortion Is Sinful"

With pro-lifers seemingly on a roll, what explains the pushback against personhood?

There are two basic branches of the pro-life movement. They both believe abortion is wrong, but one group—let's call them the "incrementalists"— believe the best way to end abortion is to gradually chip away at the availability of abortion until the procedure is so hard to obtain that it practically never happens. This wing is responsible for measures like Texas's HB2, which mandated that abortion providers gain hospital admitting privileges and meet the standards of ambulatory surgical centers. They're behind most of the abortion restrictions we've seen in the past couple of years, like forcing women to look at sonograms of their fetuses before they terminate their pregnancies, 20-week abortion bans, and limitations on medication abortion.

The other branch, let's call them "absolutists," believe the best way to stop abortion is to, well, stop abortion. That means in all cases, preferably with an across-the-board law. Personhood measures fall in this category because they would mean that "unborn human beings" meet the legal definition of a "child." This wing is motivated by the fact that no matter how many incremental restrictions are passed, there will still be some women somewhere who will manage to follow all the rules and get an abortion.

“Step-by-step measures haven’t stopped the killing,” Linda J. Theis, president of an absolutist group that broke away from Ohio Right to Life, told The New York Times in 2011.

The absolutists haven't been doing as well, though, because most voters are relatively moderate on abortion. The electorate has been almost evenly split between the "pro-life" and "pro-choice" campssince about 2000. Even if they oppose abortion in theory, most people would probably support the right of rape victims to get one—something this most recent Colorado measure would have outlawed.

What's more, personhood laws are written using very vague language—often purposefully so—so people aren't quite sure what their effect would be. North Dakota's Measure 1, for example, would have added a paragraph to the state constitution that said: "the inalienable right to life of every human being at any stage of development must be recognized and protected."

"The impact was uncertain and the thing itself was uncertain," said Mary Ziegler, a law professor at Florida State University who has studied the abortion debate.

"Voters just aren’t comfortable with restrictions that are that absolute."

The incremental approaches have proven far more popular. Tennessee, for example, passed a measure Tuesday that gives the General Assembly more flexibility to legislate abortion laws, as my colleague Emma Green wrote.

The issue facing the absolutists, Ziegler says, is that "voters are not comfortable with abortion, and they aren't comfortable with banning it."

Tuesday's election might signal the twilight of such statewide personhood ballot initiatives, if only because these defeats come at a huge political cost: They're demoralizing to activists, and they make politicians think they don't have to pay attention to pro-life voters, Ziegler says.

But the personhood movement itself, which has been around since the 1970s, isn't going anywhere. Instead, it looks like it will take a page from the incrementalists' book, moving on to push personhood measures at the city-by-city level, as the Personhood Alliance announced in a recent press release. This strategy rests on the logic that even though the Mississippi measure failed overall in 2011, it was supported by majorities in several counties.

"We know that at the local level, Planned Parenthood and the media can't match our network of churches and our tight knit conservative communities," Les Riley of Personhood Mississippi said in a statement.

Meanwhile, Ziegler said the North Dakota initiative might be seen as a bit of an innovation from the personhood movement, a kind of a middle ground between an outright ban and an incremental law and a way to get voters to decide on a statement of principle—in this case, that all fetuses are people.

These types of uber-vague initiatives could succeed in the future "if the movement does a better job of convincing voters that they know what this means," Zieger says. "But that’s the only thing that was different in this cycle. Otherwise it was the same people losing the same fight."

No comments:

Post a Comment