"Get Me Off Your Fucking Mailing List" is an actual science paper accepted by a journal

The paper above, titled "Get me off your fucking mailing list," has been accepted by the International Journal of Advanced Computer Technology.

Let us explain.

The journal, despite its distinguished name, is a predatory open-access journal, as noted by io9. These sorts of low-quality journals spam thousands of scientists, offering to publish their work for a fee.

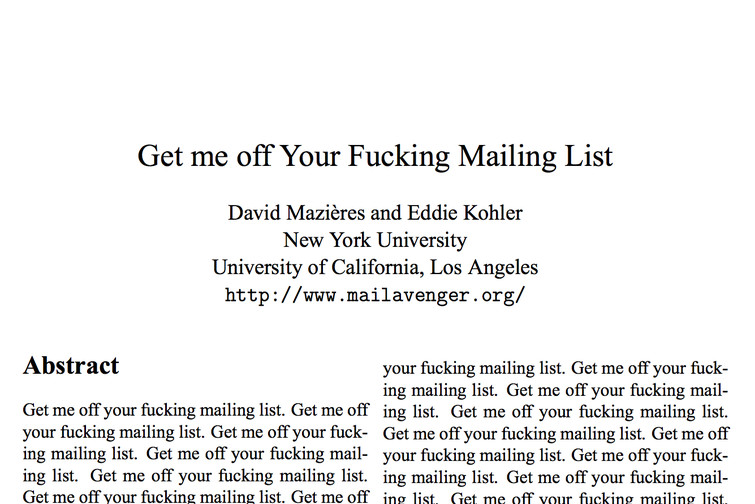

In 2005, computer scientists David Mazières and Eddie Kohler created this highly profane ten-page paper as a joke, to send in replying to unwanted conference invitations. It literally just contains that seven-word phrase over and over, along with a nice flow chart and scatter-plot graph:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2478224/Screen_Shot_2014-11-21_at_9.53.24_AM.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2478226/Screen_Shot_2014-11-21_at_9.53.39_AM.0.png)

According to the blog Scholarly Open Access, this PDF made the rounds, and an Australian computer scientist named Peter Vamplew sent it to the International Journal of Advanced Computer Technology in response to spam from the journal. Apparently, he thought the editors might simply open and read it.

Instead, they automatically accepted the paper — with an anonymous reviewer rating it as "excellent" — and requested a fee of $150.

This incident is pretty hilarious. But it's a sign of a bigger problem in science publishing. This journal is one of many online-only, for-profit operations that take advantage of inexperienced researchers under pressure to publish their work in any outlet that seems superficially legitimate. They're very different from respected, rigorous journals like Science and Nature that publish much of the research you read about in the news. Most troublingly, the predatory journals don't conduct peer-review — the process where other scientists in the field evaluate a paper before it's published.

This isn't the first time a predatory publisher has been exposed

In a several different cases, reporters have intentionally exposed low-quality journals by submitting substandard material to see if it would get published.

Last April, for instance, a reporter for the Ottawa Citizen named Tom Spears wrote an entirely incoherent paper on soils, cancer treatment, and Mars, and submitted it to 18 online, for-profit journals. Eight of them quickly accepted it, asking for $1,000 to $5,000 in exchange for publication.

Last year, science reporter John Bohannonconducted a similar stunt, with the cooperation of the prestigious journal Science. He submitted a less absurd, but deeply flawed paper about the cancer-fighting properties of a chemical extracted from lichen to 340 of these journals, and got it accepted by 60 percent of them. Using IP addresses, Bohannon discovered that the journals that accepted his paper weredisproportionately located in India and Nigeria.

Earlier this year, I carried out a sting of a predatory book publisher — a company that uses the same basic strategy, but publishes physical books of academic theses and dissertations. When they contacted me offering to publish my undergraduate thesis for no fee, I agreed, so I could write an article about it. They gained the permanent rights to my work — along with the ability to sell copies of it for exorbitant prices online — but failed to notice that I'd stuck in a totally irrelevant sentence in towards the end, highlighting the fact that they publish without proofreading or editing.

Compared to these stunts, though, "Get me off your fucking mailing list" is even more troubling. It shows that for this one journal — which claims to conduct peer review — an actual human never laid eyes on the paper before it was accepted.

Inside the weird world of predatory journals

The existence of these dubious publishers can be traced to the early 2000's, when the first open-access online journals were founded. Instead of printing each issue and making money by selling subscriptions to libraries, these journals were given out for free online, and supported themselves largely through fees paid by the actual researchers submitting work to be published.

The first of these journals were and are legitimate — PLOS ONE, for instance, rejected Bohannon's lichen paper because it failed peer review. But these were soon followed by predatory publishers — largely based abroad — that basically pose as legitimate journals so researchers will pay their processing fees.

Over the years, the number of these predatory journals has exploded. Jeffrey Beall, a librarian at the University of Colorado, keeps an up-to-date list of them to help researchers avoid being taken in; it currently has 550 publishers and journals on it.

Still, new ones pop up constantly, and it can be hard for a researcher — or a review board, looking at a resume and deciding whether to grant tenure — to track which journals are bogus. Journals are often judged on their impact factor (a number that rates how often their articles are cited by other journals), and Spears reports that some of these journals are now buying fake impact factors from fake rating companies to seem more legitimate.

Scientists view this industry as a problem for a few reasons: it reduces trust in science, allows unqualified researchers to build their resumes with fake or unreliable work, and makes research for legitimate scientists more difficult, as they're forced to wade through dozens of worthless papers to find useful ones.

Correction: This article previously said the article was published by the journal. It was only accepted, because the author didn't want to pay $150.

No comments:

Post a Comment