Alan: Gregory Bateson observed that "Natural History is the antidote for piety." The following account is one of countless thousands that obliges recognition that traditional pieties -- while useful and even necessary for many religious believers -- are not enough for people for educated people who know that Natural History unfolds with a kind of "ravaging randomness" that casts "the work of Love" in ways that have little to do with traditional pieties and the assumption that God is in Complete Control.

In the Christian tradition, Yeshua himself spotlights the inadequacy of traditional pieties in the account of "The Man Born Blind."

More recently, Jesuit paleontogist/cosmologist Teilhard de Chardin, does Christianity (and all humankind) a great service by pointing out that "Research is adoration."

***

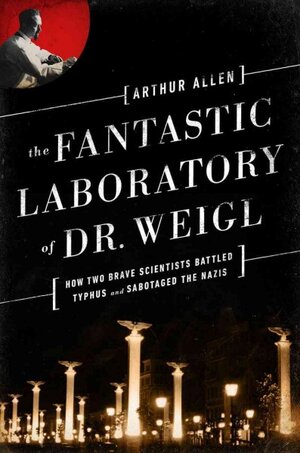

Dr. Rudolf Weigl in his lab.

Audio File: http://www.npr.org/2014/07/22/333734201/how-scientists-created-a-typhus-vaccine-in-a-fantastic-laboratory

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union during World War II, Nazi commanders had another worry besides the Red Army. Epidemics of typhus fever, which is transmitted by body lice, killed untold numbers of soldiers and civilians during and after World War I.

As World War II raged, typhus reappeared in war-torn areas and in Jewish ghettos, where cramped, harsh conditions were a perfect breeding ground for lice.

So the Nazis employed Dr. Rudolf Weigl to produce a typhus vaccine. Weigl created a technique that involved raising millions of infected lice in a laboratory and harvesting their guts to get the materials for a vaccine.

Lice that had been infected with typhus bacteria would be allowed to feed on human volunteers, says Arthur Allen, who wrote the new book The Fantastic Laboratory of Dr. Weigl. "And then, after about five days," Allen tells Fresh Air's Dave Davies,"[the lice] would be taken and dissected individually."

Scientists would pull out the "louse gut," where the typhus bacteria grow and multiply, put it in a pot and, basically, mash it up with a chemical solution to make the vaccine.

Weigl's lab in Lviv, Poland, sheltered Polish intellectuals and resistance fighters from the Nazis by employing them as lice feeders, meaning the volunteers allowed hundreds or thousands of lice — some infected with typhus, some not — to suck their blood. The lice were put in tiny cages that were attached to people's legs. To avoid catching the illness themselves, these human volunteers had to be clean, have healthy skin and be able to resist scratching.

"All the intellectual life basically migrated to Weigl's laboratory," Allen says. "There were ... tables full of mathematicians who would be doing their work as mathematicians while lice fed on their blood."

The lab sent weakened vaccines to the German army. And Weigl helped smuggle the stronger product to Jews in a Polish ghetto.

Allen says there was also a black market for the vaccine.

"It was one of the most valuable black market commodities," he says, "because it was thought as being one of the only ways you could save yourself from typhus in the ghetto."

Interview Highlights

On typhus symptoms, and how it spread

Typhus would begin with a terrible headache and back pains, leading to fever, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea; and around the time the fever began, there would be a rash that often broke out on the abdomen that was described as looking like little red jewels. ... And eventually you would have deafness, terrible hysterical fits of laughter and tears, and sometimes suicide. ... And sometimes the long-term effects could include things like loss of limbs — people were known to lose toes and fingers or a penis from gangrene.

... Back in the day ... everyone was carrying lice. And they were as much a part of our armature as our clothes. Typhus could happen in a number of different places where people were wearing their clothes and didn't change them.

... But basically, ... starting in the late 19th century, early 20th century, when people [started bathing more regularly], it became a disease that was really only associated with these very extreme situations of war — concentration camps, barracks, ghettos, places where people really didn't have running water, didn't [have] access to changes of clothes. And then it spread very quickly in these kinds of environments.

On how the disease is transmitted

People originally thought it was because of the bite, because the louse sticks a little needle into you to extract your blood. But it turns out that the mouth of the louse is actually sterile. And what happens is that as the louse bites you, it excretes, and you scratch because it itches. And when you scratch, you're sort of inoculating yourself with the bacteria that are in the louse poop, as it were.

On the Nazis' use of louse imagery

The Nazis ... always described the Jews as "vermin" and sometimes used the word "lice." ... And this was an ideology that was belittling and obviously also associating Jews with, sort of, filth and contamination, parasitism — all of these things that you metaphorically can link lice to.

[The Nazis] made it very concrete after they took over the first Polish cities. ... There were signs that went up all over Warsaw, for example ... that would have a picture of a bearded Jew with a louse that said, "Lice, Jews, typhus," to make that association in the minds [of] Poles — the idea of keeping them from protecting Jews, [of] seeing Jews as part of this invasive, parasitic, dangerous force that they had to avoid and exterminate.

On the underground community associated with Weigl's lab

During the interwar period, all of the intellectual life in Lviv, [Poland], was in the cafes. Well, the cafes were all closed during the Nazi occupation, or only Nazis went there, or collaborators. And all the intellectual life basically migrated to Weigl's laboratory.

People would go in there. ... There were geographers, poets, all kinds of biologists, every kind of walk of life. In particular, there were many university professors and students who worked there. There were also people from the Polish underground who worked there.

It was a perfect cover, to be an underground organizer, because you had this pass that said "typhus institute" on it. You showed that to a Nazi SS person. And, on the one hand, they were terrified that anyone having to do with this typhus institute could be infected with typhus, was dirty, was associated with Jews and lice. ... And, on the other hand, [the Nazis] were told not to bother these people because they were making a product that was key to the German health defense.

On the Weigl vaccine going to the German soldiers

There was a certain amount of sabotage that went on in the lab, where the doses of the vaccine that were headed for the Eastern front [to Germans] were sometimes weakened.

... In general, this was legitimate vaccine that did go to protect [the Jews'] enemies.

This is a conundrum and a paradox that's unavoidable, and it was something that everyone who worked [at the laboratories] had to struggle with. The fact was they were able to employ very few Jews of any kind in the laboratory.

And while this laboratory was protecting many people who were key Poles and key intellectuals and resistance fighters, the destruction of the ghetto was going on at the same time. ... It's something that everyone who worked there — everyone whose life was saved — had to deal with ethically, morally after and during the war.

On the approximately 30,000 vaccine doses that made their way to the Jewish ghettos

It was smuggled in various ways, but one method that Weigl had for doing this was to tell his bosses that they needed to do some experimental work with the vaccine to make sure that it was up to snuff, that it was working well. So this would be a pretense for bringing it into the ghetto and vaccinating people. ... This went on throughout the war.

On Weigl's reputation and legacy

Throughout his life and even into the '80s, there would be occasional remarks about [Dr. Weigl] in the press or in articles that he had been a collaborator.

It wasn't until after the fall of the Soviet Union [in 1991] that his reputation was rehabilitated. Some of the people who had gone to the United States or were still in Poland began to write articles.

... Then, eventually, word got to the Israeli authorities ... who recognized gentiles who did work to protect Jews during the Holocaust. [Israel] gave [Weigl] recognition belatedly in 2003 — he was named as "righteous among nations."

No comments:

Post a Comment