"The Commons" And Happiness

"The Commons," All That We Share

Excerpt: C.S. Lewis memorably wrote that art and philosophy — in other words, the substance of what we call human culture — have no survival value but, rather, give value to survival. The kind of value he had in mind, of course, was spiritual. And yet half a century later, we’ve stifled our way into a system that assesses art and philosophy and human culture for their economic value as market commodities — they’ve been reduced to that depressingly derogatory term for cultural material: content.

The People’s Platform: An Essential Manifesto for Reclaiming Our Cultural Commons in the Age of Commerce

by Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

“We are embedded beings who create work in a social context, toiling shared soil in the hopes that our labor bears fruit. It is up to all of us whether this soil is enriched or depleted, whether it nurtures diverse and vital produce or allows predictable crops to take root and run rampant.”

C.S. Lewis memorably wrote that art and philosophy — in other words, the substance of what we call human culture — have no survival value but, rather, give value to survival. The kind of value he had in mind, of course, was spiritual. And yet half a century later, we’ve stifled our way into a system that assesses art and philosophy and human culture for their economic value as market commodities — they’ve been reduced to that depressingly derogatory term for cultural material: content.

C.S. Lewis memorably wrote that art and philosophy — in other words, the substance of what we call human culture — have no survival value but, rather, give value to survival. The kind of value he had in mind, of course, was spiritual. And yet half a century later, we’ve stifled our way into a system that assesses art and philosophy and human culture for their economic value as market commodities — they’ve been reduced to that depressingly derogatory term for cultural material: content.

One chilly autumn afternoon a few years ago, I sat on a park bench in Brooklyn with writer, activist, documentary filmmaker, and kindred cautious idealist Astra Taylor to talk about how and why we got here, and what we can do to save the ennobling thought-things that give value to human survival. Ours was one of many conversations Taylor had in the process of researching and writing her magnificent and enormously important manifesto for the survival of our cultural commons, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (public library) — a look at what the internet has promised us, how it has failed us in delivering on those promises, and what we can do to shed its burdens and carry its blessings forward.

Illustration from Theodor Nelson's pioneering 1974 book 'Computer Lib | Dream Machines' found in '100 Ideas that Changed the Web.' Click image for more.

Taylor writes:

As a consequence of the Internet, it is assumed that traditional gatekeepers will crumble and middlemen will wither. The new orthodoxy envisions the Web as a kind of Robin Hood, stealing audience and influence away from the big and giving to the small. Networked technologies will put professionals and amateurs on an even playing field, or even give the latter an advantage. Artists and writers will thrive without institutional backing, able to reach their audiences directly. A golden age of sharing and collaboration will be ushered in, modeled on Wikipedia and open source software.In many wonderful ways this is the world we have been waiting for. [But] in some crucial respects the standard assumptions about the Internet’s inevitable effects have misled us.

The argument regarding the internet’s impact, Taylor notes, has become bereft of nuance and has settled into one of two camps from which soundbites are fired at the other — techno-skeptics, in the tradition of Alvin Toffler, admonish us that we’ve become a herd of “skimmers, staying in the shallows of incessant stimulation,” while techno-optimists assure us that we’re “evolving into expert synthesizers and multitaskers, smarter than ever before.” Such polarization —like all polarization — seems rather impoverishing. Much of it pits technology against humanism which, as Krista Tippett has elegantly asserted of science and spirituality, ask wholly different questions rather than providing different answers to the same question. Indeed, Taylor targets this with exquisite precision:

These questions are important, but the way they are framed tends to make technology too central, granting agency to tools while sidestepping the thorny issue of the larger social structures in which we and our technologies are embedded.

Newsgirls deliver newspapers in 1910. Public domain photograph by Lewis Hine (Library of Congress)

She notes that “new media” is quite a misnomer, for it implies both a counterpoint to and a supplanting of “old media” — and yet this is hardly the case. I, too, have often marveled at how much of Old Media’s legacy we’ve simply replicated and transposed onto new platforms — take, for instance, a newspaper editor’s remarkably prescient 1923 lament about commerce taking over cultural responsibility in journalism, or E.B. White’s 1975 admonition about the evils of corporate sponsorship in public media. Taylor agrees:

Many of the problems that plagued our media system before the Internet was widely adopted have carried over into the digital domain — consolidation, centralization, and commercialism — and will continue to shape it. Networked technologies do not resolve the contradictions between art and commerce, but rather make commercialism less visible and more pervasive… The pressure to be quick, to appeal to the broadest possible public, to be sensational, to seek easy celebrity, to be attractive to corporate sponsors—these forces multiply online where every click can be measured, every piece of data mined, every view marketed against. Originality and depth eat away at profits online, where faster fortunes are made by aggregating work done by others, attracting eyeballs and ad revenue as a result.

And yet her point is “not trying to deny the transformative nature of the Internet, but rather to recognize that we’ve lived with it long enough to ask tough questions” — questions that call on us to respond not with cynicism and resignation but with mobilized hope and lucid idealism as we peer forward into a more promising future for what proto-internet pioneer Vannevar Bush so poetically termed “the common record.” Taylor writes:

The truth is subtler: technology alone cannot deliver the cultural transformation we have been waiting for; instead, we need to first understand and then address the underlying social and economic forces that shape it. Only then can we make good on the unprecedented opportunity the Internet offers and begin to make the ideal of a more inclusive and equitable culture a reality. If we want the Internet to truly be a people’s platform, we will have to work to make it so.

Paul Otlet's Mundaneum, an early-twentieth-century analog internet human-powered by a primarily female staff who answered queries by hand. Click image for more.

For one thing, Taylor admonishes that the artists, writers, and other craftspeople of culture are being shortchanged by the machinery of commercial interest and corporate power. She writes:

Wealth and power are shifting to those who control the platforms on which all of us create, consume, and connect.[…]Cultural products are increasingly valuable only insofar as they serve as a kind of “signal generator” from which data can be mined. The real profits flow not to the people who fill the platforms where audiences congregate and communicate — the content creators — but to those who own them.[…]During this crucial moment of cultural and economic restructuring, artists themselves have been curiously absent from a conversation dominated by executives, academics, and entrepreneurs.

Some artists, of course, are raising their heads and challenging the this-is-how-it-should-be-done-because-this-is-how-it-has-always-been-done paradigm of culture’s relationship with commerce. And yet, pointing to another realm where we’ve lost our sense of nuance, Taylor argues that in our fetishism of openness at all costs — that is, at no cost — we’ve forgotten the actual, physical, inescapably tangible costs of creating what we designate by the ethereal term “culture.” In the final chapter, aptly titled “Drawing a Line,” she writes:

When we talk about the cultural commons, it should be self-evident that production is a precondition of access. An article needs to be researched and written before it can be read; a canvas must be painted before it can be shown. Yet we live in a society oddly reluctant to recognize that this is the case. Dominant economic theories emphasize exchange: the value of a good has nothing to do with how it was made but, instead, the price it can command in the marketplace.And when we try to break with the market to talk about gift economies, bestowing as opposed to buying, we still focus on the way things circulate rather than how they are created. More often than not, those who speak enthusiastically about the cultural commons stay safely inside what Karl Marx called “the noisy sphere” of consumption, “where everything takes place … in full view of everyone,” instead of descending into “the hidden abode of production,” which in fact shapes our world even if we choose to look the other way.This means we are telling only half the story.

For a glimpse of the other half, for instance, consider the fact that by this point — nearly nine years into it — just keeping Brain Pickings functionally running costs me more than my rent each month. How much it costs to produce a singleRadiolab episode or to merely keep Wikipedia’s servers going or to care for the millions of books preserved by The New York Public Library, I can only imagine — which is why I and many others donate to these creators and stewards of culture regularly. On top of these purely technical costs, of course, is the human labor — the time, thought, and love of bringing something to life — something meant to exist not because it is marketable but because it matters.

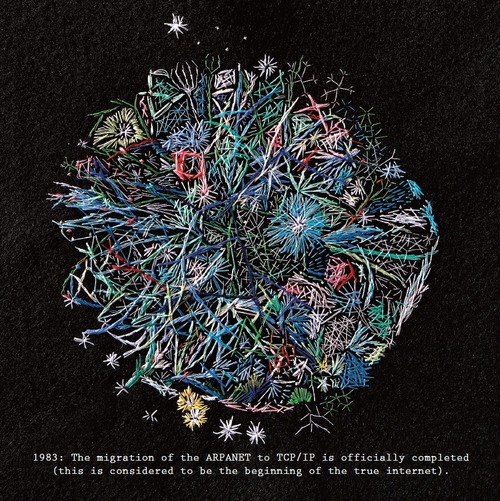

Embroidered map of the infant Internet in 1983 by Debbie Millman (courtesy of the artist)

Taylor captures this ecosystem of costs that create value beautifully:

A material reality supports the digital commons in all its facets: hardware, infrastructure, and content.[…]Creativity and commerce have a complex relationship and, in many ways, a necessary one. Nonetheless, a market in creative goods is different from creative marketing, and the latter is growing at the expense of the former. The mercantile climate has moved to the center; what was once an attribute has become a dominant feature.

Half a century after E.F. Schumacher exhorted us to stop prioritizing products over people and consumption over creativity, Taylor argues that the root cause of disturbing the vital balance between the two by drowning culture in commerce is the rise of ad-supported media. She considers the corner into which we’ve squeezed ourselves by relinquishing creative integrity for commercial profit:

The technology is still in its infancy, but we should pause to reflect on the profound nature of this transformation. Right now there are artists who agonize over whether to license their work for commercial purposes, and yet we have a situation where our very likeness is used to hawk doughnuts or shoes or whatever it may be without explicit permission being granted first. There are people going deeply into debt so they can work as journalists and truth tellers, but “sponsored content” is what they are told will pay the bills.

She worries that these changes will permeate the very fabric of what we believe is possible, and slowly warp our social standards:

Why worry about selling out when you are already an ad and have been your whole life? Why fret over the ethics of promoting yourself when you are already being used to promote something else? Under the “open” model, where the distinction between commercial and noncommercial has melted away, everything is for sale. When there is no distinction between inner and outer, our bonds with family and friends, our private desires and curiosities, all become commodities. We are sold out in advance, branded whether we want to be or not.[…]While it may look like we are getting something for nothing, advertising-financed culture is not free. We pay environmentally, we pay with our self-esteem, and we pay with our attention, privacy, and knowledge.

And yet all is not lost — far from it. While Taylor’s critique is not of the soft, compliment-sandwich kind, it is also inherently a beacon of hope rather than despair. She offers a number of strategies for fortifying our cultural commons and possible directions for expanding the horizon of the possible and living up to our potential as a species capable of honorable and ennobling deeds:

One positive step may be something deceptively simple: an effort to raise consciousness about something we could call sustainable culture. “Culture” and “cultivate” share the same root, after all: “Coulter,” a cognate of “culture,” means the blade of a plowshare. It is not a reach to align the production and consumption of culture with the growing appreciation of skilled workmanship and artisanal goods, of community food systems and ethical economies. The aims of this movement may be extended and adapted to describe cultural production and exchange, online and off.[…]We are embedded beings who create work in a social context, toiling shared soil in the hopes that our labor bears fruit. It is up to all of us whether this soil is enriched or depleted, whether it nurtures diverse and vital produce or allows predictable crops to take root and run rampant. The notion of sustainable culture forces us to recognize that the digital has not rendered all previously existing institutions obsolete. It also challenges us to figure out how to improve them.

In the remainder of The People’s Platform, which is at once immensely important and full of Taylor’s deeply enjoyable prose, she goes on to examine how we can outgrow the limiting models we’ve inherited and find more ambitious new ways of making our world more beautiful, intelligent, and full of meaning. Complement it with this history of 100 ideas that changed the web, then revisit Belgian idealist Paul Otlet’s early-twentieth-century vision for a democratic “internet” and dear old E.B. White on the role and responsibility of the writer.

No comments:

Post a Comment