In Affordable Care Act case, context is key

Ruth Marcus

As with everything else here these days, the talk about the Affordable Care Act case before the Supreme Court next week will focus on ideological splits: Will any conservative justice join the four liberals all but certain to back the administration?

In fact, the correct conservative legal position would be to rule for the administration.

The case, King v. Burwell, concerns the availability of insurance subsidies in the 34 states that opted for federally run insurance exchanges rather than setting up their own. A subsection outlining how to calculate these subsidies refers to an “exchange established by the state.”First, it would demonstrate greater deference to the constitutional rights of states within a federal system. Second, it would reflect a restrained conception of the judicial role, respecting statutory language rather than legislating from the bench.

Thus, the argument of those out to destroy the law: If Congress wanted to subsidize customers in federal exchanges, it would have done that. So, for a statutory strict constructionist, case closed.

Not so fast.

I’ll dispense with the statutory interpretation issue first, and take guidance from Justice Antonin Scalia, an undoubted conservative, who literally wrote the book on statutory interpretation.

Scalia’s approach is termed “textualist,” in contrast to the loosey-goosier “purposivist” method of those who see the court’s role as reading a statute in light of its underlying legislative intent. A purposivist would have no trouble deciding this case: The Affordable Care Act is designed to cover as many uninsured as possible.

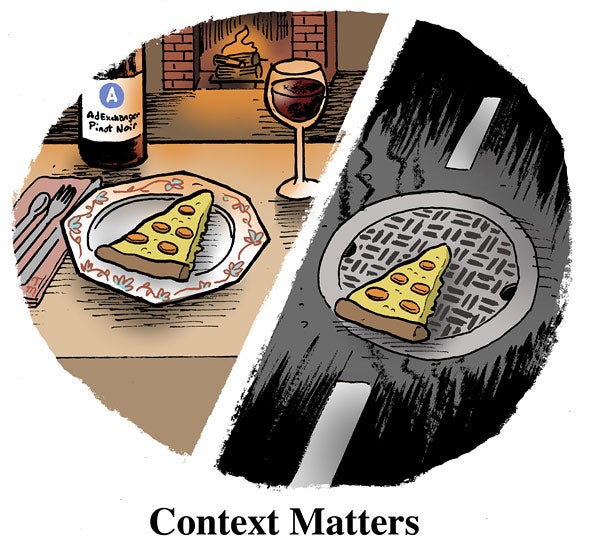

But a good textualist would rule for the government, too, looking solely to the structure and language of the law. First, “it is a fundamental canon of statutory construction that the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.”

That language comes from the Supreme Court’s 2000 ruling rejecting the Food and Drug Administration’s bid to regulate tobacco. It was written by then-Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and joined by Justices Scalia, Anthony Kennedy and Clarence Thomas. (Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito weren’t yet serving.)

In the ACA case, the text must be read in the context of other provisions that would be rendered absurd if subsidies were limited to state-operated exchanges.

To take one example: No one could buy insurance on federal exchanges because the statute defines an individual “qualified” to purchase as one who “resides in the state that established the exchange.”

So under the challengers’ reading, Congress would have taken the trouble to establish exchanges not only doomed to fail, because of the unavailability of subsidies, but that would have no customers at all.

A second rule of statutory construction is that Congress “does not alter the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme in vague terms or ancillary provisions — it does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes.” That comes from a 2001 Scalia opinion, joined by Kennedy and Thomas.

In this case, according to the challengers, Congress hid quite an elephant — a provision that even they agree would gut the law — in a five-word mousehole.

Which brings me to the states’-rights issue that, for conservatives, should be even more compelling. The ACA created federal exchanges as the states’ backup plan, respecting states’ rights to choose.

Under the challengers’ reading, this federalist flexibility would be transformed into federal punishment: Citizens of states that failed to establish exchanges would be deprived of subsidies, sending the federal exchanges into a death spiral. Individual insurance markets in those states would collapse, too, because other provisions in the law — such as requiring insurers to cover preexisting conditions — would still apply, driving sicker people into those markets and premium costs up.

All without any warning to states that these consequences were coming. The prospect that subsidies would not be available on state exchanges never arose during congressional debate. If Congress really intended to hammer states that failed to set up exchanges, would it have hidden its threat in an obscure subsection?

It’s indisputable that states were blindsided by this possibility. “Regardless of who runs the exchange, the end product is the same,” said Ohio Gov. John Kasich, a Republican. By “refusing to implement state-based exchanges, the state is ceding nothing,” said South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, also a Republican.

Interpreting the law to bar subsidies would embody the judicial activism the conservatives repeatedly disavow, elevating policy antipathy to the health-care law over settled legal principles.

Read more from Ruth Marcus’s archive

No comments:

Post a Comment