Mapping 61 Ancient Tattoos on a 5,300-Year-Old Mummy

Scientists used a modified Nikon camera to reveal previously unseen markings on Ötzi the Iceman's body.

Wearing a surgical mask and gown over a thick winter jacket, Marcello Melis stood at a glass operating table in a tiny ice chamber and examination room in Italy’s South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. His patient was a 5,300-year-old mummy nicknamed “Ötzi the Iceman.” And though Melis wanted to look beneath Ötzi’s caramel-colored skin, he held neither a scalpel nor forceps in his gloved hands. Rather, the tool for this procedure was a modified Nikon camera.Ötzi is legendary in science circles. Since finding the frozen mummy in the Italian Alps in 1991, researchers have conducted numerous tests to piece together his ancient tale. Genomic sequencing suggests that he had brown eyes, and came from Central Europe, as well as was lactose intolerant and predisposed for coronary heart disease. Analysis of a shoulder wound indicated he was fatally shot with an arrow that pierced an artery. And a CT scan showed he also suffered a hard blow to the head. Radiolab did a whole show about the murder mystery ofÖtzi’s demise. But what fascinated Melis and his colleagues most were the faded, yet still visible black tattoos that covered the mummy's wrists, ankles, and lower back.

The thing is: Researchers never knew how many tattoos Ötzi had, or why exactly he was inked in the first place. They’d previously counted somewhere between 47 and 55 black simple charcoal lines rubbed into the iceman’s skin, mostly around his joints. Some scientists believe that the tattoos were made using a sharp bone tool in an attempt to alleviate pain in these areas, perhaps an early form of acupuncture.

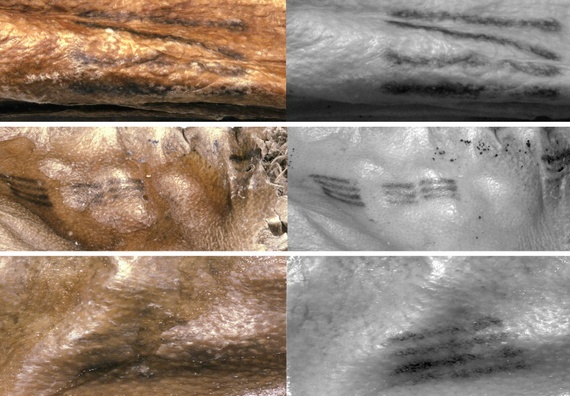

So Melis and his colleague Matteo Miccoli from Profilocolore, a spectral imaging company in Rome, teamed up with the museum’s mummy experts and used a camera technique called Hypercolorimetric Multispectral Imaging (HMI) to investigate. The idea was to analyze Ötzi under infrared and ultraviolet light, which might reveal details that couldn't otherwise be seen. Using specialized lenses on an otherwise ordinary Nikon and imaging software, Melis and his colleagues analyzed every pixel from the photos they took under seven different wavelengths of light to map Ötzi’s tattoos.

And it worked. Not only did Melis and his team get a more complete view of tattoos they already knew were there—they also uncovered new markings on parts of Ötzi’s body they never knew were decorated.

Before his work on Ötzi, Melis had used the HMI technique to collect clues for a more traditional sort of cold case. After Italian police found the bones of a missing man who had disappeared years earlier, Melis used the camera technique at the crime scene to identify traces of blood splattered on what looked like clean walls. The finding led a judge to reopen the case as a homicide. Melis also used the technique to reveal a Leonardo da Vinci mural hidden beneath a thick layer of soot in an Italian castle. Doctors use the technique to diagnose dermatological diseases such as melanoma that can be present beneath the surface of the skin—an application not unlike the method researchers used to identify Ötzi’s tattoos. “We thought we could use the same kind of technique to discover the tattoos on the mummy, because the tattoos go under the skin,” Melis said.

Melis and his team found a total of 61 tattoos across the mummy’s body—including a never before seen set located on his ribcage. They reported their findings last month in the Journal of Cultural Heritage. “The tattoo on the chest was really surprising, we did not expect to find a completely new tattoo,” said the anthropologist Albert Zink, head of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Research Academy in Italy, and an author on the paper.

The finding may challenge prevailing theories about the tattoos' therapeutic properties. In the paper, Zink suggests that because of its location, the new chest tattoo seems to contradict the idea that the markings only alleviated lower back and joint pain. “The question is now, ‘Is this also a treatment? Or is this symbolic, or even for a religious function?'” Zink said.

Walter Kean, a rheumatologist from McMaster University in Canada who was not involved with the study, previously published a paper suggesting Ötzi’s tattoos are related to pain in the iceman’s back, transitional vertebra, and legs. “If some or all of the iceman’s tattoos were used as markers for therapeutics—then the chest tattoos could easily be a marker for some form of chest pain which troubled the iceman,” he said in an email.

Frank Rühli, director of the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine in Zurich, Switzerland, who also was not involved with the most recent study, cautions against interpreting the chest markings as pain management signs. “It's fascinating work,” he said. “But for me atherosclerosis is not a good enough reasoning for the marks. I see it for the joints, but for the atherosclerosis I’m not very convinced.”

As the debate on whether the tattoos served a therapeutic, religious, or symbolic purpose continues, Melis notes that nobody knows the true meaning behind the subdermal markings. “Before we discovered the new ones they thought it was acupuncture,” said Melis. “But then we discovered one on the ribcage and we thought, ‘This is something that has nothing to do with the joints.’ So now the mystery is back.”

No comments:

Post a Comment