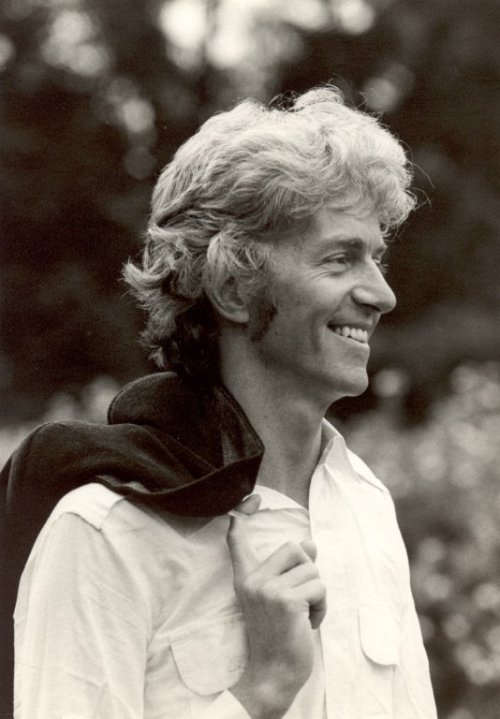

Derek Parfit has few memories of his past and almost never thinks about it,

a fact that he attributes to an inability to form mental images.

How to Be Good

An Oxford philosopher thinks he can distill all morality into a formula. Is he right?

BY LARISSA MACFARQUHAR

What makes me the same person throughout my life, and a different person from you? And what is the importance of these facts?I believe that most of us have false beliefs about our own nature, and our identity over time, and that, when we see the truth, we ought to change some of our beliefs about what we have reason to do.

You are in a terrible accident. Your body is fatally injured, as are the brains of your two identical-triplet brothers. Your brain is divided into two halves, and into each brother’s body one half is successfully transplanted. After the surgery, each of the two resulting people believes himself to be you, seems to remember living your life, and has your character. (This is not as unlikely as it sounds: already, living brains have been surgically divided, resulting in two separate streams of consciousness.) What has happened? Have you died, or have you survived? And if you have survived who are you? Are you one of these people? Both? Or neither? What if one of the transplants fails, and only one person with half your brain survives? That seems quite different—but the death of one person could hardly make a difference to the identity of another.

The philosopher Derek Parfit believes that neither of the people is you, but that this doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that you have ceased to exist, because what has happened to you is quite unlike ordinary death: in your relationship to the two new people there is everything that matters in ordinary survival—a continuity of memories and dispositions that will decay and change as they usually do. Most of us care about our future because it is ours—but this most fundamental human instinct is based on a mistake, Parfit believes. Personal identity is not what matters.

Parfit is thought by many to be the most original moral philosopher in the English-speaking world. He has written two books, both of which have been called the most important works to be written in the field in more than a century—since 1874, when Henry Sidgwick’s “The Method of Ethics,” the apogee of classical utilitarianism, was published. Parfit’s first book, “Reasons and Persons,” was published in 1984, when he was forty-one, and caused a sensation. The book was dense with science-fictional thought experiments, all urging a shift toward a more impersonal, non-physical, and selfless view of human life.

Suppose that a scientist were to begin replacing your cells, one by one, with those of Greta Garbo at the age of thirty. At the beginning of the experiment, the recipient of the cells would clearly be you, and at the end it would clearly be Garbo, but what about in the middle? It seems implausible to suggest that you could draw a line between the two—that any single cell could make all the difference between you and not-you. There is, then, no answer to the question of whether or not the person is you, and yet there is no mystery involved—we know what happened. A self, it seems, is not all or nothing but the sort of thing that there can be more of or less of. When, in the process of a zygote’s cellular self-multiplication, does a person start to exist? Or when does a person, descending into dementia or coma, cease to be? There is no simple answer—it is a matter of degrees.

Parfit’s view resembles in some ways the Buddhist view of the self, a fact that was pointed out to him years ago by a professor of Oriental religions. Parfit was delighted by this discovery. He is in the business of searching for universal truths, so to find out that a figure like the Buddha, vastly removed from him by time and space, came independently to a similar conclusion—well, that was extremely reassuring. (Sometime later, he learned that “Reasons and Persons” was being memorized and chanted, along with sutras, by novice monks at a monastery in Tibet.) It is difficult to believe that there is no such thing as an all-or-nothing self—no “deep further fact” beyond the multitude of small psychological facts that make you who you are. Parfit finds that his own belief is unstable—he needs to re-convince himself. Buddha, too, thought that achieving this belief was very hard, though possible with much meditation. But, assuming that we could be convinced, how should we think about it?

Is the truth depressing? Some may find it so. But I find it liberating, and consoling.

(Parfit’s words, in his books, in e-mails, and even in speech, all have a similar timbre—it is difficult to distinguish them. In all, a strong emotion is audible under restraint.)

When I believed that my existence was such a further fact, I seemed imprisoned in myself. My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.

It seems to a friend of Parfit’s that his theory of personal identity is motivated by an extreme fear of death. But Parfit doesn’t believe that he once feared death more than other people, and now he thinks he fears it less.

My death will break the more direct relations between my present experiences and future experiences, but it will not break various other relations.

Some people will remember him. Others may be influenced by his writing, or act upon his advice. Memories that connect with his memories, thoughts that connect with his thoughts, actions taken that connect with his intentions, will persist after he is gone, just inside different bodies.

This is all there is to the fact that there will be no one living who will be me. Now that I have seen this, my death seems to me less bad.

After Parfit finished “Reasons and Persons,” he became increasingly disturbed by how many people believed that there was no such thing as objective moral truth. This led him to write his second book, “On What Matters,” which was published this summer, after years of anticipation among philosophers. (A conference, a book of critical essays, and endless discussions about it preceded its appearance, based on circulated drafts.) Parfit believes that there are true answers to moral questions, just as there are to mathematical ones. Humans can perceive these truths, through a combination of intuition and critical reasoning, but they remain true whether humans perceive them or not. He believes that there is nothing more urgent for him to do in his brief time on earth than discover what these truths are and persuade others of their reality. He believes that without moral truth the world would be a bleak place in which nothing mattered. This thought horrifies him.

We would have no reasons to try to decide how to live. Such decisions would be arbitrary. . . . We would act only on our instincts and desires, living as other animals live.

He feels himself surrounded by dangerous skeptics. Many of his colleagues not only do not believe in objective moral truth—they don’t even find its absence disturbing. They are pragmatic types who argue that the notion of moral truth is unnecessary, a fifth wheel: with it or without it, people will go on with their lives as they have always done, feeling strongly that some things are bad and others good, not missing the cosmic imprimatur. To Parfit, this is an appalling nihilism.

Subjectivists sometimes say that, even though nothing matters in an objective sense, it is enough that some things matter to people. But that shows how deeply these views differ. Subjectivists are like those who say, “God doesn’t exist in your sense, but God is love, and some people love each other, so in my sense God exists.”

Parfit is an atheist, but when it comes to moral truth he believes what Ivan Karamazov believed about God: if it does not exist, then everything is permitted.

In the way that he moves and carries himself, Parfit gives the impression of one who is unaware of being looked at, perhaps because he spends so much time alone. He clutches his computer bag. He fidgets. His hair is white and fluffy and has settled into a pageboy of the kind that was fashionable for men in the fifteenth century. He wears the same outfit every day: white shirt, black trousers.

There is something not-there about him, an unphysical, slightly androgynous quality. He lacks the normal anti-social emotions—envy, malice, dominance, desire for revenge. He doesn’t believe that his conscious mind is responsible for the important parts of his work. He pictures his thinking self as a government minister sitting behind a large desk, who writes a question on a piece of paper and puts it in his out-tray. The minister then sits idly at the desk, twiddling his thumbs, while in some back room civil servants labor furiously, come up with the answer, and place it in his in-tray. Parfit is less aware than most of the boundaries of his self—less conscious of them and less protective. He is helplessly, sometimes unwillingly, empathetic: he will find himself overcome by the mood of the person he is with, especially if that person is unhappy.

He has few memories of his past, and he almost never thinks about it, although his memory for other things is very good. He attributes this to his inability to form mental images. Although he recognizes familiar things when he sees them, he cannot call up images of them afterward in his head: he cannot visualize even so simple an image as a flag; he cannot, when he is away, recall his wife’s face. (This condition is rare but not unheard of; it has been proposed that it is more common in people who think in abstractions.) He has always believed that this is why he never thinks about his childhood. He imagines other people, in quiet moments, playing their memories in their heads like wonderful old movies, whereas his few memories are stored as propositions, as sentences, with none of the vividness of a picture. But, when it is suggested to him that an absence of images does not really explain an absence of emotional connection to his past, he concedes that this is so.

Parfit’s mother, Jessie, was born in India to two medical missionaries. She grew up to study medicine—she was a brilliant student and won many prizes. She joined the Oxford Group, a Christian movement, founded in the nineteen-twenties, whose members strove to adhere to the Four Absolutes: absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute unselfishness, and absolute love. Through the Oxford Group, she met Norman Parfit, the son of an Anglican clergyman, who was also studying to be a doctor. Norman was a bad student, but he was funny and gregarious and principled—he was a pacifist and a teetotaller. After he received the group’s permission to propose, he and Jessie married.

In 1935, soon after they became doctors, Norman and Jessie moved to western China to teach preventive medicine in missionary hospitals. Before they were able to begin work, they were required to spend a couple of years in the mountains studying Chinese. Jessie picked it up easily, but Norman simply could not learn the language, however hard he tried, and he despaired over his failure. Their first child, Theodora, was born in 1939, and their second, Derek, in 1942. Norman was drawn to Mao’s idealist ardor. He didn’t become a Communist, exactly, but he abandoned the conservative political views with which he was brought up. More significantly, both Norman and Jessie lost their faith. They disliked some of their fellow-missionaries, some of whom were quite racist, and they were struck by the irrelevance of Christianity to a sophisticated culture like China’s. Jessie shed her faith easily—she associated Christianity with the oppressive puritanism of her upbringing, and found purpose enough in public health. But Norman’s loss of faith was a catastrophe. Without God, his life had no meaning. He sank into a chronic depression that lasted until his death.

About a year after Derek was born, the family left China. They settled in Oxford, and had a third child, Joanna. When Derek was seven, he became religious and decided to be a monk. He prayed all the time and tried vainly to persuade his parents to go to church. But at eight he lost his faith: he decided that a good God would not send people to Hell, and so if his teachers were wrong about God’s goodness they must also be wrong about God’s existence. His argument was flawed but convincing—he never believed in God again.

Jessie and Norman had little in common and grew unhappy together, but they stayed married. Jessie took a second degree, became a psychiatrist, and ended up running London’s services for emotionally disturbed children. Norman worked at a low-level public-health job near Oxford. He was concerned about cancer and fluoridation, but he was too ineffectual to do much about either.

My father was a perfectionist, who achieved little. He labored for several weeks each year to write his Annual Report, whose text he continually revised. My mother would have written such a report in an hour or two. Though he was, in some ways, an intellectual, to whom moral and religious ideas mattered greatly, I believe that he read, as an adult, only two books: Thackeray’s “Henry Esmond,” which he was given, and “Away with All Pests,” which described a successful Chinese campaign to destroy disease-carrying flies.

All three children were sent to boarding school when they were young, so they didn’t know each other very well.

I remember becoming aware that, for most children, home was where they lived, and not merely, as it was for me, a place that I visited for brief interruptions to my main life that was lived at school.

Theodora and Derek were brilliant students, like their mother. Derek was sent to Eton, where he came first in every subject except mathematics. Joanna, like her father, was bad at everything. Her teeth stuck out. She was also much too tall—six feet at the age of eleven. When the family was together, it was awful—Norman was angry almost all the time. He often didn’t understand what his wife and elder children were talking about, and this made him feel inferior. He had a narrow life. He took refuge in two hobbies—tennis, which he didn’t play well, and stamp collecting, on which he spent several hours each evening. Parfit emerged from his childhood with the understanding that he and his mother and Theo were lucky and would live full lives, while Norman and Joanna were unlucky and would never be happy. For the rest of his life, his father and his younger sister represented for him everything that horrified him about suffering and unfairness.

I was not, I believe, badly affected by my father’s depression. I was merely very sorry for him. That is because I was never closely related to him. He wasn’t good at interacting with children. Before I left for my years as a Harkness Fellow in the U.S., I noticed tears in my father’s eyes when he said goodbye to me. That moved me greatly at the time, and I find tears in my eyes as I type this sentence. That was the only time in which I had some sense of the love that my father, in his depressed and inarticulate way, felt for me.

In the early summer of 1961, Parfit, aged eighteen, travelled to New York. He was nearly turned down for a visa—the immigration officer saw that he was born in China and told him the Chinese quota was already full. He protested that he was British; the officer consulted with a colleague and informed him that he would get a visa since he was the sort of Chinese person they liked. He went to work at The New Yorker, as a researcher for The Talk of the Town. He stayed in a splendid high-ceilinged apartment on the Upper West Side with his sister Theo and several of her friends from Oxford—mostly returning Rhodes scholars. He brimmed with enthusiasms and self-confidence and issued pronouncements on all sorts of subjects, which amused some of the Rhodes scholars and irritated others.

He loved jazz, and went often to hear Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. He had always loved music, but he couldn’t play an instrument, because he couldn’t read the notes—he could slowly work them out, but not with any fluency. He hypothesized that there was some relationship between his inability to read music and his deficiencies at mathematics: he was not good at processing symbols.

He had wanted to be a poet since he was nine or ten. He published one poem, “Photograph of a Comtesse,” in The New Yorker the year after he worked there, and several in the Eton College Chronicle.

. . . A fierce tug on the lineJerked you back. You pulled at once—leaping betweenDelight and horror that the line you woundWas tearing a pointed hook through flesh. . . .You held the fish,Then lashed it savagely against the deckAnd threw the battered pulp far out to sea. . . .With sickness in your throat you went belowAnd lay half-sick till port.

He spent months laboring on his poetry, but he developed an obsession with the idea that not only should the lines of a poem rhyme but the words within each line should have internal assonances, with repeated patterns of consonants or vowels, as is the case in some Anglo-Saxon and German poetry. But it was so difficult to find words that had both the right sound and the right sense that he found he could no longer finish a poem. His obsession became crazier and more crippling. Now when he read his favorite poets—Shakespeare, Keats, Tennyson—their poems seemed to him badly flawed, because they had too few internal assonances. He understood that this was insane, but he couldn’t help it. Eventually, he realized that he stood no chance of becoming a good poet and gave up.

In the autumn of 1961, he went up to Oxford to read history. (He studied Modern History at Eton, which for England began when the Romans left, in 410.) He was a little bored by the subject, and briefly considered switching to P.P.E.—Philosophy, Politics and Economics. He was apprehensive about the mathematics that economics would involve, however, so he read a few pages of a textbook and came across a symbol he didn’t recognize—a line with a dot above and a dot below. He asked someone to explain it, and when he was told that it was a division sign he felt so humiliated that he decided to stick with history. After Oxford, he went back to America for two years on a Harkness Fellowship.

He decided to study philosophy. He attended a lecture by a Continental philosopher that addressed some important subject such as suicide or the meaning of life, but he couldn’t understand any of it. He went to hear an analytic philosopher who spoke on a trivial topic but was quite lucid. He wondered whether it was more likely that Continental philosophers would become more lucid or analytic philosophers less trivial. He decided that the second was more likely, and returned to Oxford. Almost at once, he achieved a dazzling success: he took an exam and won a Prize Fellowship at All Souls, which entitled him to room and board at the college for seven years, with no teaching duties. He studied with A. J. Ayer, Peter Strawson, and David Pears. He was electrified by the belligerence of philosophers—historians were much milder—although he worried that his delight was inconsistent with his disapproval of other pugilistic sports, such as boxing.

He moved into rooms at All Souls and settled into a monk-like existence. There was usually a woman in his life somewhere, but he spent very little time with her. Almost all his waking hours were spent at his desk. All Souls resembles a monastery. Its fifteenth-century stone arcades surround a vivid lawn that is immaculate because it is seldom used: All Souls has no undergraduates and is not often open to the public—its gates are shut. All his needs were taken care of by the college: he was housed, fed, and paid, and nothing in the way of emotional output was required of him. This was how his life had been since he went to boarding school, at ten, and it suited him. He had become, he realized, what psychiatrists call institutionalized—a person for whom living in an institution feels more normal than living in a family. The only thing that interfered with his work was a lack of sleep. He suffered from terrible insomnia—when he went to bed his brain kept racing, and there were many days when he was too exhausted to work. But when he was in his mid-thirties his doctor prescribed a tricyclic antidepressant, Amitriptyline, with which, along with a very large quantity of vodka, he could force himself into unconsciousness.

Sometime after he gave up the idea of being a poet, Parfit developed a new aesthetic obsession: photography. He drifted into it—a rich uncle gave him an expensive camera—but later it occurred to him that his interest in committing to paper images of things he had seen might stem from his inability to hold those images in his mind. He also believed that most of the world looked better in reproduction than it did in life. There were only about ten things in the world he wanted to photograph, however, and they were all buildings: the best buildings in Venice—Palladio’s two churches, the Doge’s Palace, the buildings along the Grand Canal—and the best buildings in St. Petersburg, the Winter Palace and the General Staff Building.

I find it puzzling how much I, and some other people, love architecture. Most of the buildings that I love have pillars, either classical or Gothic. There is a nice dismissive word that applies to all other buildings: “astylar.” I also love the avenues in the French countryside, perhaps because the trees are like rows of pillars. (There were eight million trees in French avenues in 1900, and now there are only about three hundred thousand.) There are some astylar buildings that I love, such as some skyscrapers. The best buildings in Venice and St. Petersburg, though very beautiful, are not sublime. What is sublime, I remember hearing Kenneth Clark say, are only the interiors of some late Gothic cathedrals, and some American skyscrapers.

Although he admired some skyscrapers, he believed that architecture had generally declined since 1840, and the world had grown uglier. On the other hand, anesthetics were discovered around the same time, so the world’s suffering had been greatly reduced. Was the trade-off worth it? He was not sure.

He believed that he had little native talent for photography, but that by working hard at it he would be able to produce, in his lifetime, a few good pictures. Between 1975 and 1998, he spent about five weeks each year in Venice and St. Petersburg.

I may be somewhat unusual in the fact that I never get tired or sated with what I love most, so that I don’t need or want variety.

He disliked overhead lights, in which category he included the midday sun, but he loved the horizontal rays at the two ends of the day. He waited for hours, reading a book, for the right sort of light and the right sort of weather.

When he came home, he developed his photographs and sorted them. Of a thousand pictures, he might keep three. When he decided that a picture was worth saving, he took it to a professional processor in London and had the processor hand-paint out all aspects of the image that he found distasteful, which meant all evidence of the twentieth century—cars, telegraph wires, signposts—and usually all people. Then he had the colors repeatedly adjusted, although this was enormously expensive, until they were exactly what he wanted—which was a matter of fidelity not to the scene as it was but to an idea in his head.

Other than his trips to Venice and St. Petersburg, the only reason he left All Souls for any length of time was to travel to America, to teach. He had appointments at Harvard, Rutgers, and N.Y.U.: he wanted students, because he found that it was discouragingly difficult to persuade older philosophers to change their minds. He also needed students, because only they would talk philosophy with him for twelve hours at a stretch and then wake up the next day wanting to do it again. Older philosophers (and his students from past years were now in this category) had children and spouses; they sat on academic committees and barbecued in their back yards. Only he stayed the same—as fervently single-minded as they were, too, when they were young. When he found a bright new student to mentor, he devoted hours to reading his work and writing comments. (He did this for many colleagues as well: he read with astonishing speed, and would often return a manuscript with densely argued comments that were longer than the manuscript itself, even if the manuscript was a book.)

When he was in America, he was compelled to procure his own food. Because he didn’t want to waste time on choice or preparation, he developed rigid routines that he could follow without thinking. For years, according to a colleague, he made the same meal every morning for breakfast, which he conceived of as a recipe for maximum health: sausage links, green peppers, yogurt, and a banana, all in one bowl. One day, the colleague’s nutritionist wife explained to him that this was not a particularly healthy meal, and suggested a better meal; the next day he switched to the new meal and never varied it.

He was always conscious of how little time he had. When he had to go from one building to another on a big American campus, he ran. But his routines were not just about time-saving: he found himself constantly returning to the same thoughts, philosophical and otherwise—that was just the way his mind worked. “At one point, I spent a year at Harvard when he was visiting there and we would go out to dinner,” Larry Temkin, a philosopher and former student of his, says. “We went to the same place, a Thai restaurant, every time, and every time he would order some curry and I would order something that had pineapples and rice and cashews. And every time he’d say, ‘Larry, isn’t that boring, don’t you want some of my curry?’ I’d say, ‘No, Derek, I don’t like curry, it’s too spicy for me.’ And then the next week we’d go to the same restaurant, and he would order the same meal, and I would order the same meal, and he’d say, ‘Larry, isn’t that boring, don’t you want some of this?’ And I’d say, ‘No, Derek, I really don’t, you like the curries, but they’re too spicy for me.’ And the next week the same thing would happen again. It was like ‘Groundhog Day.’ ”

Theo Parfit married an American, settled outside Washington, D.C., and had three children. She studied social work and became an expert on families. She wrote about how to hold families together in a crisis, and about ways to involve families in the education of their children. Although she lived far away, she kept in touch with her parents and siblings and cousins. She tried to see her brother when he came to the East Coast, as he frequently did, to teach, but usually he didn’t call. He didn’t do this to avoid her—it simply didn’t occur to him, because he was thinking about philosophy. She knew this, and tried not to feel hurt. When they did see each other, he was very friendly.

Parfit lived near his parents in Oxford, and saw them once a week, for Sunday lunch. His mother read up on philosophy to try to understand his work, but since Parfit saw her only with his father they couldn’t talk much about it. His father was baffled by him; he couldn’t understand why he became a philosopher—he thought he ought to have been a scientist. He tried, unsuccessfully, to interest his son in tennis.

Joanna struggled to find work. Finally, she managed to qualify as a nanny. She became pregnant and had a son, Tom, whom she raised on her own. A few years later, she adopted a daughter. She loved her children, but they didn’t make her happy. Every few months, she telephoned Parfit to talk to him about how depressed she was and how badly things were going. He dreaded those calls. Then, in her thirties, she died in a car crash.

She had not made a will, and after she died there was a harrowing fight over her son. Her daughter was re-adopted quickly, but Jessie was determined that Tom should be placed in a family she knew. The trouble was, his placement was in the hands of the local council, and Jessie so antagonized the council with her uncompromising opinions and her upper-middle-class accent that it sought actively to thwart her. Jessie was in agony, and Parfit became very emotionally involved. The case ended up in court, and he wrote a long and passionate brief supporting his mother. At last, the case was resolved in their favor. Jessie died soon afterward, although she was not sick or particularly old. Once Tom was safely placed with his new family, nearby, Parfit never saw him.

As the years went by, Theo came to accept that although her brother loved her, it was simply not important to him to spend time with his family. He was extremely softhearted, and she knew that in a crisis he would always help her, but deepening ties to his past through continuity, valuing blood as a source of kinship—these were just not part of who he was. Years later, Parfit wrote to her in a letter that they had reacted to their unhappy family in opposite ways. They were like the Rhine and the Danube: they begin very close, but then they diverge—one flows to the Atlantic, the other to the Black Sea.

Sometime around 1982 or ’83, the philosopher Janet Radcliffe Richards moved from London to Oxford, having ended her first marriage. She had become well known a few years earlier for writing “The Skeptical Feminist,” a fierce attack on anti-rational tendencies in the women’s movement, and was teaching philosophy of science at the Open University. She was very beautiful and very feminine. She attended a seminar that Parfit was teaching. She had never encountered anyone like him: he was obviously a strange person, but not in any of the usual ways. Afterward, Amartya Sen, a friend, who was co-teaching the seminar, greeted her, and, when she left, Parfit asked Sen who she was.

D.P.: I read some of Sam Scheffler’s recent work and he’s arguing that people care about the future of humanity much more than they realize. And I think that’s right, actually.J.R.R.: The Future of Humanity Institute people keep talking about engineering humans to make them more moral. I haven’t got a clear enough view of what it would be, because it would have to be something so different from humans that I’m not sure why bother, any more than turn everybody into termites or something.D.P.: Oh no! You could—J.R.R.: The essence of us is that the things we value are close connections and families and groups, and that necessarily means that we care about other people less.

At the time, Parfit was preparing the manuscript of “Reasons and Persons” for the printer. This involved a certain amount of anxiety, but the enormous intellectual labor that had consumed him for fifteen years was over. He was entering a rare transitional moment, between decades-long periods of total philosophical immersion, in which his mind was, for a short time, receptive to other things.

Parfit read Richards’s book and wrote her a letter about it, suggesting that they meet and discuss it further. He went out and bought three identical black suits. They met. He offered to rent her a computer. (He had just discovered computers—he had bought one secondhand and was very excited about it.) With unpracticed but single-minded diligence, he pursued her.

She was bewildered. An eminent philosopher had sent her a letter that in tone and content resembled an academic article, and now he was offering to rent her a computer. How much did it cost to rent a computer? He had not named an amount. He certainly seemed very interested in talking with her, and he was charming and brilliant and unexpectedly good-looking, but what was he up to? He never flirted—he talked to her exactly as he would talk to a man. After a time, she deduced from the sheer frequency of his attentions that his interest must be romantic, but this was not apparent in his behavior. She began to wonder if he would propose to her before they had kissed.

D.P.: I think there’s great scope for change, even with no genetic changes.J.R.R.: Oh, I wasn’t talking about with no genetic changes, I was talking about the genetic ones they were talking about. Of course there’s scope for change, but the question is how much they’re going to work with the material we’ve got, and how much they’re going to change it—and they want to change it a lot. You could see there could be a society of some kind of being that lived in perfect harmony, but I can’t quite see the point.D.P.: Well, Nick Bostrom said that it’s no good having moral intelligent robots if they’re not conscious, so he is aware that you have to make sure they’re conscious.J.R.R.: I suppose I just have trouble thinking that there is a point in having things exist if they aren’t things that are wanted by things that already happen to exist. I can’t see the point of bringing anything into existence out of nothing. I don’t see why the world is better with creatures in it than not, especially as there’s so much suffering.

Richards didn’t realize how unusual this transitional moment was in Parfit’s life. Soon, having won her, Parfit burrowed back into his work. At first, this was fine—she didn’t want a man around all the time—but then they decided to buy a house together. They had intended to look in Oxford, but Parfit lost his heart to a beautiful eighteenth-century house near Avebury, a Neolithic henge monument in Wiltshire. He had to have it—he bid the price up and was terribly anxious until the deed was signed. Then, happy to have won his house, he sat in his study with the blinds down. Ten minutes away, there was a glorious bluebell wood, and he loved bluebell woods—one of his fears about global warming was that it would get too hot for bluebells—but Richards couldn’t get him to go there. It existed: that was enough. Eventually, she realized that her need for human company, modest as it was, was greater than he was capable of meeting. They sold the house, she bought a house in London, and he went back to his rooms in All Souls. From then until he retired, more than ten years later, they spent very little time together, although they spoke on the phone several times a day.

Around the mid-nineties, Parfit started reading Kant. He hadn’t read him seriously before because he had always found him irritating—his appalling sentences (it was Kant, he felt, who had made really bad writing philosophically acceptable), his grandiloquence, his infuriating inconsistencies and glaring mistakes. He felt that the crucial Kantian idea of autonomy, for instance, was just a blatant cheat: Kant wanted there to be a universally valid moral law, and he wanted every person to have the moral autonomy to determine the law for himself, and he just couldn’t accept that you couldn’t have both those things at once.

I asked a Kantian, “Does this mean that, if I don’t give myself Kant’s Imperative as a law, I am not subject to it?” “No,” I was told, “you have to give yourself a law, and there’s only one law.” This reply was maddening, like the propaganda of the so-called People’s Democracies of the old Soviet bloc, in which voting was compulsory and there was only one candidate. And when I said “But I haven’t given myself Kant’s Imperative as a law,” I was told “Yes you have.”

Things that mattered enormously to Kant—moral autonomy, motive—didn’t seem that important to Parfit. He thought that individual selves were less significant than other people thought they were, so he wasn’t that interested in motive; he thought that moral truths existed independently of human will, so he wasn’t going to place much value on autonomy in Kant’s sense. The driving force behind Parfit’s moral concern was suffering. He couldn’t bear to see someone suffer—even thinking about suffering in the abstract could make him cry. He believed that no one, not even a monster like Hitler, could deserve to suffer at all. (He realized that there were practical reasons to lock such people up, but that was a different issue.)

Parfit’s first love in moral philosophy was someone completely unlike Kant—Henry Sidgwick, the British consequentialist, best known for “The Methods of Ethics.” Sidgwick was very boring. He was so boring that he even considered himself boring. He was boring because he was very, very thorough. He would hedge each claim with so many potential rebuttals, and counter-rebuttals, and counter-counter-rebuttals, that a reader was apt either to throw the book down in exasperation or to become so muddled in the jostling of hypothetical interlocutors that he had no idea what he was supposed to think. Sidgwick realized this, but he felt that it was more important to be careful than to be exciting, and that whatever value his work possessed depended on that care. He was a modest man. Kant wrote of his “Critique” that it “rests on a fully secured foundation, established forever; it will prove to be indispensable too for the noblest ends of mankind in all future ages”; Sidgwick wrote of his “Methods” that it “solves nothing, but may clear up the ideas of one or two people, a little.” But though there were other philosophers more original and more brilliant, Parfit felt that Sidgwick’s “Methods,” in its precise, dull way, captured more important truths about morality than any other book ever written. It was not surprising to him that a plodder like Sidgwick should write a better book than a genius like Plato or Kant, since he believed that philosophy was like science—over time, it made progress.

As he read deeper and deeper into Kant, he began to feel that the grandiloquence and inconsistency that had irritated him in the past were the product of an emotional nature so passionately extreme that it was simply incapable of Sidgwick’s careful self-criticism. For Kant, something was never just good, it was necessary; there was little “most” or “some” in Kant, only “all” or “none.” Parfit recognized that he, too, was an emotional extremist who found it difficult to accept answers that fell between everything and nothing. But as he began to appreciate Kant—he came to believe that Kant was the greatest moral philosopher since the ancient Greeks—he began to be more and more troubled by the ways in which Kant diverged from Sidgwick, and by the way that modern Kantians disagreed with modern consequentialists and both disagreed with contractualists. Kantians thought that you should act according to categorical moral principles that you believe ought to be followed by everyone; you should not lie, for instance, even if a murderer asks you to tell him where your friend is, so he can kill him. The important thing is to do your duty, whatever happens as a result. But consequentialists believed that results—consequences—were everything: what was important was not motive or adherence to rules but bringing about as much good as possible. Contractualists believed that the crucial thing was consent: the way to figure out what to do was to imagine the principles to which nobody could reasonably object. The trick was to arrange the thought experiment so the consent wasn’t the kind of pseudo consent that had so irritated Parfit in Kant—it had to be the consent of plausibly self-interested people, not rational ghosts.

There were brilliant philosophers of good faith in all three camps, he knew, so why were their disagreements so intractable? If philosophers just as clever and well versed as he was disagreed with him, how could he be sure he was right? What if he could prove that their differences were only an illusion of perspective—that at a certain point all three approaches converged, like climbers scaling different sides of a mountain and meeting at the summit? Then he would be able to feel much more confident in his conviction that moral truths existed and it was possible to discover them.

In 2002, he gave the Tanner Lectures on Human Values at U.C. Berkeley, proposing an early draft of his solution. He began circulating a book manuscript titled “Climbing the Mountain.” One of his moves was to point out the problems with so-called “act consequentialism” as opposed to “rule consequentialism.” Act consequentialists were purists: they believed that each action should be considered on its own merits, with the one simple idea of increasing well-being. But not only did this pose the considerable practical problem that most people would likely be pretty bad at anticipating the consequences of their actions; it would also make social life virtually impossible. It might make sense to lie to a murderer, but if there were no rules about lying it would be difficult to trust anyone—even the lie to the murderer would be ineffective. Similarly, it might in one case seem right for a mother to sacrifice her child so that ten strangers could live, but a society in which mothers were always eager to sacrifice their children for strangers would be dreadful, so better to have a rule favoring maternal love and let the occasional stranger perish.

Parfit’s main task, however, was to prove that Kantianism and rule consequentialism were not actually in conflict. To do this, he needed to perform surgery on Kant’s Formula of Universal Law, the formula that Kant had claimed to be the supreme principle of morality: “I ought never to act except in such a way that I could also will that my maxim should become a universal law.” Many Kantians had given up on this formula (Kant had many others), concluding that it simply didn’t help to distinguish right from wrong. But Parfit went to work on it, hacking off a piece here, suturing on a piece there, until he had arrived at a version that seemed to him to combine the best elements of Kantianism and contractualism: “Everyone ought to follow the principles whose universal acceptance everyone could rationally will.” He argued that these principles would be the same ones that were espoused by rule consequentialism. Then, at last, he was in a position to propose his top-of-the-mountain formula, which he called the Triple Theory:

An act is wrong just when such acts are disallowed by some principle that is optimific, uniquely universally willable, and not reasonably rejectable.

The theory’s principles were consequentialist because they would lead to the best results (optimific); Kantian because they were universally willable; and contractualist because no person could reasonably reject them.

Parfit wanted his book to be as close to perfect as it could possibly be. He wanted to have answered every conceivable objection. To this end, he sent his manuscript to practically every philosopher he knew, asking for criticisms, and more than two hundred and fifty sent him comments. He labored for years to fix every error. As he corrected his mistakes and clarified his arguments, the book grew longer. He had originally conceived of it as a short book; it became a long book, and then a very long book supplemented by an even longer book—fourteen hundred pages in all. People began to wonder if he would ever finish.

With his Triple Theory, Parfit believed that he had achieved convergence between three of the main schools of moral thought, but even this didn’t satisfy him. There were still major philosophers outstanding whom he admired but whose views disturbed him. He marshalled every possible argument, however quixotic, to prove that what appeared to be irreconcilable differences were merely errors of little significance.

When Hume claims . . . that such preferences are not contrary to reason, he is forgetting, or mis-stating, his normative beliefs. We should distinguish between Hume’s stated view and his real view. Though Nietzsche makes some normative claims that most of us would strongly reject, some of these claims are not wholly sane, and others depend on ignorance or false beliefs about the relevant non-normative facts. And Nietzsche often disagrees with himself.

There were so many facts we did not yet know, Parfit felt, so many distorting influences of which we were not yet aware, and it was always so easy to make mistakes. However hopeless the situation might appear, it seemed to him that, in the end, humans converged toward moral progress.

When Parfit was young, one of the most dazzling figures on the philosophical scene was Bernard Williams. Williams was thirteen years older than Parfit and already had a formidable reputation. He was urbane, seductive, and witty—he was famous for his eviscerating put-downs and scathing repartee. He acknowledged the originality of Parfit’s work, but, socially, he was dismissive. Williams was a club man, a college man, full of High Table bonhomie; Parfit would gobble his dinner and, while other fellows met for brandies, dessert, and cigars, he would hurry back to his room.

Williams lived a rich, worldly life. He had flown Spitfires in the Air Force. He had lived for years in a large house in London with his first wife, the politician Shirley Williams, their daughter, and another couple. He had an affair with another man’s wife and left his wife for her; they married and had two sons. He sat on royal commissions and government committees, issuing opinions on pornography, drug abuse, private schools, and gambling. (He had done, he liked to say, all the vices.) He wrote about opera.

Williams had started out in classics, and his thinking was formed as much by Greek tragedy as by philosophy—he saw the world in terms of fate, shame, and luck. He thought most moral philosophy was empty and boring. He disdained both Kantianism and consequentialism, and devoted much of his career to destroying them. Both required you to think impersonally, impartially, out of duty, considering others to be as important as yourself; but we cannot andshould not become impartial, he argued, because doing so would mean abandoning what gives human life meaning. Without selfish partiality—to people you are deeply attached to, your wife and your children, your friends, to work that you love and that is particularly yours, to beauty, to place—we are nothing. We are creatures of intimacy and kinship and loyalty, not blind servants of the world.

If he had a highest value, it was authenticity. To him, the self was, in the end, all we have. But, in most cases, this wasn’t much—most people were stupid and cruel. Williams enjoyed his life, but he was a pessimist of the bleakest sort. He told a student that the last stanza of Matthew Arnold’s poem “Dover Beach” summed up his view of things:

Ah, love, let us be trueTo one another! for the world, which seemsTo lie before us like a land of dreams,So various, so beautiful, so new,Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain . . .

Williams thought that meta-ethics—questions about the existence and nature of moral truths—was especially pointless. The idea of moral truth was a delusion, he thought—the fantasy of an “argument that will stop them in their tracks when they come to take you away.” Philosophy was an art, not a science, an enterprise not of discovery but of conflict. Williams did not propose a moral theory of his own. He was skeptical that any such theory could be plausible, and anyway his brilliance was fundamentally destructive.

Parfit admired Williams more than almost anyone he knew. “Once, Derek showed me a photograph of Bernard Williams when he was provost of King’s College, Cambridge,” Larry Temkin says. “Bernard was standing on the roof of King’s College with a kind of haughty, British, aristocratic look—you know, master of all he surveys, and all of Cambridge was shown below in the distance. And Derek said, ‘Isn’t he wonderful?’ I’ve seen that only once before with him, with a picture of Rudolph Nureyev. Nureyev was in the air, way above the ground, and he had that look on his face—in a certain way it was similar to the one Bernard had—he knew, as he was floating, that he was sort of godlike. And Derek said, ‘Look at that—isn’t that just amazing?’ ”

Because he admired Williams so much, it greatly distressed him that their views were so far apart. What he found most disturbing was Williams’s view of meta-ethics. Williams believed that there were no objectively true answers to questions of right and wrong, or even to questions of prudence. To him, morality was a human system that arose from human wants and remained dependent on them. This didn’t mean that people felt any less fiercely about moral questions—if someone felt that cruelty was vile, he could believe it wholeheartedly even if he didn’t think that that vileness was an objective fact, like two plus two equals four. But, to Parfit, if it wasn’t true that cruelty was wrong, then the feeling that it was vile was just a psychological fact—flimsy, contingent, apt to be forgotten.

For morality to matter, there had to be real reasons to care about it—objective facts about what was good and worth achieving. But if, like Williams, you believed that our only reasons for acting were our desires, then if a person desired bad or crazy things—to cause someone great pain; to cause himself great pain—there could be no decisive argument against pursuing them.

Williams says that, rather than asking Socrates’ question “How ought we to live?” we should ask, “What do I basically want?” That, I believe, would be a disaster. There are better and worse ways to live.

After years of agonizing over his inability to convince Williams of his position, Parfit decided that it only appeared that Williams rejected the idea of moral truths—that in fact he simply didn’t have the concept. Williams had often said that he didn’t understand what it would mean to have the sort of reasons Parfit talked about. Parfit had always taken this to be a rhetorical gambit, but now he thought that maybe Williams meant it literally. After all, he was a very brilliant philosopher, and if he said he didn’t understand something, then one ought to believe him. This thought came as a relief: if all those years he and Williams had not actually been disagreeing but just talking past each other, then there was hope for convergence after all.

But there could never be any real convergence. Williams died in 2003. Even years later, Parfit would tell people over and over again how he had loved him. He would break down in tears when he thought of how he had never been able to get Williams to see what he saw about the truth, and now he never would.

Parfit moved out of All Souls last year. Since then, he and Richards have been living together in a brick terrace house in Oxford that he bought some years ago in preparation for this moment. They are more or less camping—the house is in need of considerable repair, and they are sharing it with two Latvian construction workers, who sleep in what will eventually be the dining room. The house was built for a smaller, daintier species than twenty-first-century humans—Parfit, who is quite tall, strides through its pocket rooms and up its tiny, twisting staircases like Alice in Wonderland. But the house dates from the right era—before 1840—and stands among others of its kind on a quiet, empty lane near the Ashmolean Museum.

D.P.: Oh gosh, you’re like those gloomy Scandinavians.J.R.R.: I am?D.P.: Well, you said it’s not worth having new conscious beings, given all the suffering. The gloomy Scandinavians think life, even at its best, is only just worth living.J.R.R.: No, no, it isn’t that, it’s just that, if nothing existed, I don’t see why it would count as better if things started existing. I can see the value of things once you’ve got people existing.D.P.: Well, that’s the person-affecting view. You haven’t read Part Four of “Reasons and Persons.”

Now that Parfit no longer lives in college, he and Richards eat dinner together most nights. By explicit mutual agreement, they never discuss his new book. She has not read it yet. They do, however, talk about philosophy.

D.P.: Suppose we discovered some technique whereby we could lengthen all of our lives so that we live happily for a few hundred years, but the cost is we’d all be sterile—so we’d be the last generation. Now, your view might be, Well, there’s no moral objection to that. It’s not going to be worse for the people who don’t exist—they’re never going to exist, so there’s no one for whom it’s going to be worse.

J.R.R.: I’m just not convinced that it is worse. I can see that we have feelings that it is, but I can’t see any objective way in which nonexistence is worse than existence. Maybe it is.D.P.: You don’t mean that if a child dies young who would’ve had a very good life, nothing bad has happened because the child doesn’t exist, and not existing isn’t a bad state to be in!J.R.R.: I think once you’ve started, the reasons are there for the existing people.D.P.: Well, I agree they’re not exactly the same, but the point in common—J.R.R.: Yes, well, they can have a point in common without it being the morally relevant point in common. You can’t just say things resemble each other in some respects, therefore you draw the same inferences.D.P.: So would your view be—J.R.R.: I haven’t really got much of a view.

Last August, after nearly thirty years together, they married. They went to the registry office, then brought a picnic to the river and went punting. Although they married partly for tax reasons, Parfit found himself unexpectedly delighted by the change. Richards’s sister took photographs of him that day, squinting into the sun, wearing a red tie, beaming.

Meanwhile, Richards was helping him through the last throes of his book’s production. He had involved himself in every detail—the font, the size of the type, the darkness of the type, the color of the paper, the printing of the jacket. He had finished the book he had toiled over with his whole mind for fifteen years, just as he was moving out of the college he had lived in for more than forty years, and in the same week he had married, after nearly seventy years of living more or less alone. The shock of these three transformative events in such a short time was more than he understood. One evening, Richards was helping him pack up his rooms, and everything was chaos around him; he was supposed to fly to America the next day, and he was trying to print out proofs of his book so he could take them with him on the plane. He had a wireless connection from his room to the college office where the printer was, so he set the thing going, and ran downstairs to check on it, but then something went wrong, so he ran up again, and down again, becoming more and more frantic. And then suddenly he collapsed. He seemed to give up.

I can’t remember what’s happening.

Richards took him to the doctor. He had transient global amnesia, a syndrome sometimes precipitated by overwhelming mental stress. He didn’t remember getting married. He didn’t remember having written his book. The doctor asked him if he knew who Richards was.

Yes. She’s the love of my life.

He recovered his memory after a few hours, but smaller aftershocks have continued. Many times he has broken down in tears—while giving a public lecture, in conversation, in class. Once again he is in a transitional moment, having finished a book, and submerged parts of his life are surfacing. He is more conscious than ever of a shortness: how much more time does he have?

A fourteen-year-old girl wants a baby. If she has one, she will be unable to give him a good start in life. If she has her first baby at twenty-five instead, she will be able to give him a better start in life—but that would be a different baby. So whom is she harming by giving birth at fourteen? No one. Not the baby, as long as his life is worth living.

Suppose we who are living now decide to ignore global warming, with the result that the lives of future people are much harder. It would seem that we have made things worse for those future people. But, in fact, as long as their lives are worth living this is not the case—because if we had acted differently, the world would have been different, and those particular people would never have existed (in the same way that if cars had not been invented most people alive today would never have been born). So, although we have made the world worse in the future, we have made life worse for no one. Parfit calls this conundrum the Non-Identity Problem. He believes that it makes no difference: we still have just as much reason to avoid making life worse for people in the future. But he worries—rightly, as it turns out—that other people may draw the opposite conclusion: since global warming will not make particular future people worse off, it may seem less bad.

Parfit has always been preoccupied with how to think about our moral responsibilities toward future people. It seems to him the most important problem we have. Besides the issue of global warming, there is the issue of population. It would seem that if the earth were teeming with many billions of people, making everyone’s life worse, that would be bad. But what if the total sum of human happiness would be higher with many billions of people whose lives were barely worth living—higher, that is, than with a smaller population of well-off people? Wouldn’t the first situation be, in some moral sense, better? Parfit calls this the Repugnant Conclusion. It seems absurd, but, at least for a consequentialist, its logic is difficult to counter.

The future makes everything more complicated, which is, apart from its enormous importance, why he likes to think about it. The first paper Parfit wrote after he began to study philosophy was on the metaphysics of time. Now this is the subject to which he plans to return. There are so many things about time that he finds puzzling.

When people describe time’s passage, they often say that we are moving into the future, or that future events are getting closer, or that nowness, or the quality of being Now, is moving down the series of events like a spotlight moving along a line of chorus girls. But these claims, though they can seem deeply true, make no sense.

Why, Parfit wonders, are we so biased toward the future? Was this tendency produced by natural selection? We are upset when we are told that in the future we shall have to endure a day of great pain, but many people do not care at all if they are told that they endured pain in the past that has been forgotten; and yet the past pain is just as real. We don’t have the same bias with other people: if we learn that a loved person suffered greatly before he died, we are upset by this, even though it’s over. The past is just as real as the present. If someone we loved is dead, that person isn’t real now. But that’s just like the fact that people who are far away aren’t real here.

I am now inclined to believe that time’s passage is an illusion. Since I strongly want time’s passage to be an illusion, I must be careful to avoid being misled.

Parfit is very struck by how little time humans have existed on the earth compared with how long they may exist in the future. He remembers as a boy hearing Bertrand Russell on the radio, talking about memories of his grandfather, who was born in 1792. When Parfit thinks about the future, he wonders whether life for future people will be better or worse than it is now. He wants to be optimistic, but he cannot ignore the terrible suffering that people have endured in the past. Has it all been worth it? Has the sum of human happiness outweighed the sum of suffering?

I am weakly inclined to believe that the past has been in itself worth it. But this may be wishful thinking.

He sees that we have the ability to make the future much better than the past, or much worse, and he knows that he will not live to discover which turns out to be the case. He knows that the way we act toward future generations will be partly determined by our beliefs about what matters in life, and whether we believe that anything matters at all. This is why he continues to try so desperately to prove that there is such a thing as moral truth.

I am now sixty-seven. To bring my voyage to a happy conclusion, I would have to resolve the misunderstandings and disagreements that I have partly described. I would need to find ways of getting many people to understand what it would be for things to matter, and of getting these people to believe that certain things really do matter. I cannot hope to do these things myself. But . . . I hope that, with art and industry, some other people will be able to do these things, thereby completing this voyage. ♦

No comments:

Post a Comment