Maya Angelou - NPR Obituary

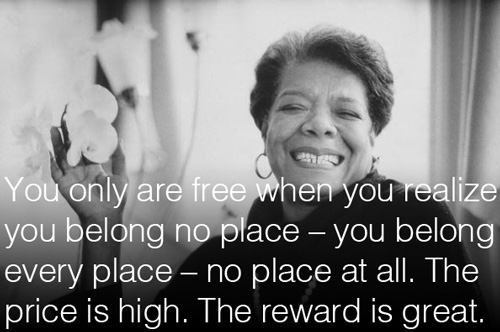

A woman "fearlessly ready to go home," ebulliently confident of God's unfailing Love.

http://www.npr.org/2014/05/28/316728741/the-life-of-poet-maya-angelou-from-poverty-to-presidential-prizes

Maya Angelou and the power of pain, audacity and joy

When the news broke this morning that Dr. Maya Angelou died at 86, after a long and almost outrageously full life, some of the early reaction I saw seemed to be preemptively defending her memory, anxious that the line of greeting cards she licensed or her tendency to present herself as a sage or presenter of maxims not be counted too heavily against her legacy.

It is true that Angelou’s tendency toward the sweeping made her a ripe target for parody in her lifetime. But on this afternoon of her death, it is impossible to separate that sense of grandeur from her audacity and her impact on American culture.

Francis Heaney, working at the now-defunct Modern Humorist, rewrote “On the Pulse of Morning,” the poem Angelou recited at Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993, to be about yoga training. “Here on the pulse of this new day/ May you have the grace under pressure to look / Straight into your student’s eyes, into / Your pupil’s face, your acolyte / And say simply / Very simply / With hope / I’m sorry you threw your back out, / please for the love of God don’t sue me,” Heaney wrote, skewering Angelou and the rise of a new fitness craze in a single stroke. Who can forget David Alan Grier’s spot-on impersonations of Angelou on Saturday Night Live, particularly in one bit where he played her as a spokeswoman for Froot Loops?

But as much as Angelou’s grandiosity could be and was lampooned, it was also a powerful weapon. If your project is to convince your readers and audiences that black women’s lives matter, both as subject material and as a statement of self-esteem, you had better be prepared to make strong claims of significance on their behalf to counteract centuries of abuse, neglect and invisibility. Angelou was.

Recalling her experience with her 1972 movie “Georgia, Georgia,” she made the case, in an interview with George Plimpton in 1990, that you could not substitute for a black woman’s perspective.

“In the theater and in film, racism and sexism stand at the door. I’m the first black female director in Hollywood; in order to direct, I went to Sweden and took a course in cinematography so I would understand what the camera would do,” Angelou told the Paris Review audience. “Though I had written a screenplay, and even composed the score, I wasn’t allowed to direct it. They brought in a young Swedish director who hadn’t even shaken a black person’s hand before. The film was Georgia, Georgia with Diana Sands. People either loathed it or complimented me. Both were wrong, because it was not what I wanted, not what I would have done if I had been allowed to direct it.”

Afro-American Sunyatta

Angelou knew the power of repeated injuries, and she was not afraid to demand they be treated with appropriate proportion.

“If growing up is painful for the Southern Black girl, being aware of her displacement is the rust on the razor that threatens the throat,” she wrote in “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings,” making clear the lethality of a constant litany of slights and insults.

That autobiography, a revelation when it was published in 1969 for its frank treatment of sexual violence, economic discrimination, racism and the inadequacies of the justice system, now feels a bit like “Casablanca.” If you read the former or watch the latter after first being exposed to their many imitators, it is easy for both to seem like cliches. But while “Casablanca” entered the flow of the culture, “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings” changed the course of that river, letting new tributaries feed into it, providing new jetties from which readers who did not see themselves in much literature could set sail in its waters.

Given the weight of some of Angelou’s subject matter, she could have been pulled under by it. Reading her poetry today, though, it is clear that one of her accomplishments was a persistent sense of fun, joy and sensuality.

Her poetry discussed fun as a defense against being pathologized as nothing but poor, in poems like “Weekend Glory,” where Angelou’s protagonist noted that “Folks write about me. / They just can’t see / how I work all week / at the factory. / Then get spruced up / and laugh and dance / And turn away from worry / with sassy glance.”

In “Phenomenal Woman,” Angelou declared that sensuality was neither predictable nor easily commodified, reminding readers of the poverty off their own standards of beauty: “Now you understand / Just why my head’s not bowed. / I don’t shout or jump about / Or have to talk real loud. / When you see me passing, / It ought to make you proud. / I say, / It’s in the click of my heels, / The bend of my hair, / the palm of my hand, / The need for my care.”

Joy could even conquer the past, as in “Still I Rise“: “Does my sexiness upset you?” Angelou asked her audience. “Does it come as a surprise / That I dance like I’ve got diamonds / At the meeting of my thighs? / Out of the huts of history’s shame / I rise / Up from a past that’s rooted in pain / I rise / I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide, / Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.”

Yes, she was. Whatever the contours she left on the sand, Angelou brought other travelers in with her, and our shores are richer for them.

No comments:

Post a Comment