STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- NEW: Hearing concludes with no immediate decision from judge

- Stinney is the youngest person to be executed by an American state since the 1800s

- According to police, he confessed to killing two girls, ages 7 and 11, in 1944

- Attorneys argued Tuesday at a hearing to determine whether there will be a new trial

updated 9:25 PM EST, Wed January 22, 2014

(CNN) -- Almost 70 years ago, South Carolina electrocuted 14-year-old George Stinney, the youngest person to be executed by an American state since the 1800s. Family members today say he's innocent, and while they can't bring him back, they want his name cleared.

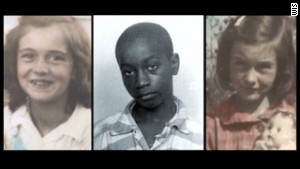

A black teen in the Jim Crow South, Stinney was accused of murdering two white girls, ages 7 and 11, as they hunted for wildflowers in Alcolu, about 50 miles southeast of Columbia.

Stinney, according to police, confessed to the crime. No witness or evidence that might vindicate him was presented during a trial that was over in fewer than three hours. An all-white jury convicted him in a flash, 10 minutes, and he was sentenced to "be electrocuted, until your body be dead in accordance with law. And may God have mercy on your soul," court documents say.

Fewer than three months after the girls' deaths, Stinney was escorted to an electric chair at a Columbia penitentiary, built for much larger defendants. The chair's straps were loose on Stinney's 5-foot-1-inch, 95-pound frame, and books were placed on the seat so he would fit in the chair.

When the switch was flipped, Stinney's body convulsed, dislodging the oversized mask and exposing his face to about 40 witnesses, including the slain girls' fathers, according to James Gamble, son of the Clarendon County sheriff at the time. Gamble recalled the execution for The Herald in Rock Hill a decade ago.

Now, attorneys for Stinney's family are demanding a new trial, saying the boy's confession was coerced and that Stinney had an alibi, his sister, Amie Ruffner, who claims she was with Stinney when the murders occurred.

"We think we have the opportunity here to make a difference and correct a wrong that's been there for 70 years," defense attorney Matt Burgess said.

Lawyers on both sides argued Tuesday at a hearing to determine whether there will be a new trial.

The defense put up witnesses related to Stinney and a forensic pathologist. Evidence in the case now seems to suggest Stinney was innocent and points to various violations of due process, Burgess said.

"South Carolina still recognizes George Stinney as a murderer. We felt that something needed to be done about that," he said.

(The police) were looking for someone to blame it on, so they used my brother as a scapegoat.

Amie Ruffner, sister of George Stinney

Amie Ruffner, sister of George Stinney

Third Circuit Solicitor Chip Finney feels differently.

"The fact of the matter is, it happened, and it occurred because of a legal system of justice that was in place and that, we -- for all we know, based on the record -- that it worked properly," he said, according to CNN affiliate WIS.

The two-day hearing concluded Wednesday with no immediate decision from the judge.

'They used my brother as a scapegoat'

Defense attorneys said Stinney's former cellmate, Wilford Hunter, issued a statement saying Stinney denied committing the crime, WIS reported.

"I didn't, didn't do it,' " Hunter recalled Stinney telling him. "He said, 'Why would they kill me for something I didn't do?' "

Ruffner, Stinney's sister, told CNN affiliate WLTX that she and Stinney saw Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, the day they died. Stinney and Ruffner were tending to their family's cow near some railroad tracks close to their home.

"They said, 'Could you tell us where we could find some maypops?' " Ruffner recalled. "We said, 'No,' and they went on about their business."

The girls were found the next day in a water-logged ditch with injuries to their head. Mary had a 2-inch laceration above her right eyebrow and a vertical laceration over her left, according to a 1944 medical examiners' report.

"Both of these are jagged and deep and there is a hole going straight through the cranial cavity from the one on the forehead. The frontal bone just above the right orbit is also definitely broken," the report says, adding there were also two bruised, lacerated areas on top of the head that appear to have been caused by a hammer.

"There is a punched out fracture of the skull beneath each of them," it says.

With Betty, "There were evidences of at least seven blows on the head," which, like Mary's injuries, appear to be the product of a "blunt instrument with a small round head about the size of a hammer. Some of these have only cracked the skull while two have punched definite holes in the skull. The back of the skull is nothing but a mass of crushed bones," the report says.

While the medical examiner noted no signs of sexual assault to Mary's body, there was some swelling on Betty's genitalia and a "slight bruise." Both girls' hymens were intact, according to the report.

Police would later say that Stinney confessed he wanted to have sex with Betty.

A handwritten statement from a law enforcement officer named H.S. Newman said that after finding the girls, "I arrested a boy by the name of George Stinney. He then made a confession and told me where to find a piece of iron about 15 inches long were (sic). He said he put it in a ditch about six feet from the bicycle."

I believe he got what he deserved, was put to death. He was old enough to know better.

Frankie Bailey Dyches, niece of victim

Frankie Bailey Dyches, niece of victim

A few days later, Ruffner told WLTX, police took Stinney and another of her brothers away in handcuffs while their parents were not at home. One brother was released, she said, while Stinney faced police questioning without his parents or a lawyer.

What followed, according to Stinney's supporters, was a farce of a trial in which Stinney's defense cross-examined no witnesses and presented no evidence or testimony in his favor.

"(The police) were looking for someone to blame it on, so they used my brother as a scapegoat," Ruffner said.

'There wasn't ever any doubt'

But not everyone believes Stinney's innocence is clear cut. The sheriff's son, Gamble, for one, told The Herald in his 2003 interview that he was in the back seat with Stinney as Gamble's father drove him to the prison in Columbia.

"There wasn't ever any doubt about him being guilty," he told the paper. "He was real talkative about it. He said, 'I'm real sorry. I didn't want to kill them girls.' "

Betty Binnicker's nieces also have their doubts, they told WIS.

"I was always told George Stinney killed her," Carolyn Geddings told the station.

Added Frankie Bailey Dyches, "I believe he got what he deserved, was put to death. He was old enough to know better."

Bailey Dyches added that she feels "justice was served, according to the laws in 1944 when this happened."

Neither relative believes the push for a new trial is warranted.

"I don't think somebody that was found guilty of a murder like he committed should be exonerated for any reason," Geddings told WIS. "And with him being gone as long as he's been gone, I think it's foolishness."

No comments:

Post a Comment