Michel de Montaigne

Wikipedia

***

Don’t worry about death, pay attention, read a lot, give up control, embrace imperfection.

“Living has yet to be generally recognized as one of the arts,” Karl De Schweinitz wrote in his 1924 guide to the art of living. But this is an art best understood not as a set of prescriptive techniques but, per Susan Sontag’s definition of art, a form of consciousness — which means an understanding that is constantly evolving.

“Living has yet to be generally recognized as one of the arts,” Karl De Schweinitz wrote in his 1924 guide to the art of living. But this is an art best understood not as a set of prescriptive techniques but, per Susan Sontag’s definition of art, a form of consciousness — which means an understanding that is constantly evolving.

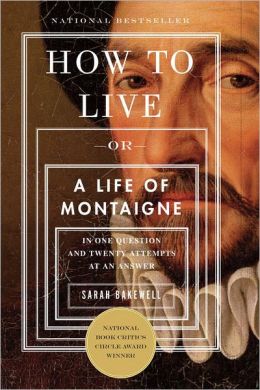

In How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer(public library), British biographer and philosophy scholar Sarah Bakewell traces “how Montaigne has flowed through time via a sort of canal system of minds” and argues that some of the most prevalent hallmarks of our era — our compulsive immersion in various forms of lifestreaming, our incessant social sharing, our constant oscillation between introspection and extraversion as we observe our private experiences more closely than ever so we can record and frame them more perfectly in public — can be traced down to this one proto-blogger, the godfather of the essay as a genre:

This idea — writing about oneself to create a mirror in which other people recognize their own humanity — has not existed forever. It had to be invented. And, unlike many cultural inventions, it can be traced to a single person: Michel Eyquem de Montaigne, a nobleman, government official, and winegrower who lived in the Périgord area of southwestern France from 1533 to 1592.

What separated Montaigne from other memoirists of his day was that he didn’t write about his daily deeds and his achievements — rather, he contemplated the meaning of life from all possible angles, and in the process popularized the essay as a form. He began writing fairly late in life, when he was thirty-nine, and continued for twenty years, halted only by his death in 1592. The 107 essays he penned range across the entire spectrum of human concerns — from the grandly existential, like death and the art of living, to the universally human, like fear and friendship and sadness and love, to the seemingly trivial, like the customs of dress. Above all, however, he was interested in the simple yet infinitely profound question of how to live — which, Bakewell is careful to point out, is quite different from the ethical prescription of how we should live. She writes:

Moral dilemmas interested Montaigne, but he was less interested in what people ought to do than in what they actually did. He wanted to know how to live a good life — meaning a correct or honorable life, but also a fully human, satisfying, flourishing one. This question drove him both to write and to read, for he was curious about all human lives, past and present. He wondered constantly about the emotions and motives behind what people did. And since he was the example closest to hand of a human going about its business, he wondered just as much about himself.

Despite the enormity of social and cultural change that has transpired in the centuries since Montaigne’s writings, however, what makes them endure and enthrall is their timeless relatability — that special skill he had of speaking to the most universal preoccupations of the human condition, yet speaking to each of us individually, leaving us with an unshakable sense of being seen and understood down to the depths of our most private selves. Indeed, writer Bernard Levin captured this beautifully in a 1991 Times article, observing: “I defy any reader of Montaigne not to put down the book at some point and say with incredulity: ‘How did he know all that about me?’” Blackwell considers how Montaigne was able to do that so elegantly:

Montaigne was the first writer to create literature that deliberately worked in this way, and to do it using the plentiful material of his own life rather than either pure philosophy or pure invention. He was the most human of writers, and the most sociable. Had he lived in the era of mass networked communication, he would have been astounded at the scale on which such sociability has become possible: not dozens or hundreds in a gallery, but millions of people seeing themselves bounced back from different angles.[…]From the first sixteenth-century neighbor or friend to browse through a draft from Montaigne’s desk to the very last human being (or other conscious entity) to extract it from the memory banks of a future virtual library, every new reading means a new Essays. Readers approach him from their private perspectives, contributing their own experience of life. At the same time, these experiences are molded by broad trends, which come and go in leisurely formation. Anyone looking over four hundred and thirty years of Montaigne-reading can see these trends building up and dissolving like clouds in a sky, or crowds on a railway platform between commuter trains.[…]The Essays is thus much more than a book. It is a centuries-long conversation between Montaigne and all those who have got to know him: a conversation which changes through history, while starting out afresh almost every time with that cry of “How did he know all that about me?” Mostly it remains a two-person encounter between writer and reader. But sidelong chat goes on among the readers too; consciously or not, each generation approaches Montaigne with expectations derived from its contemporaries and predecessors. As the story goes on, the scene becomes more crowded. It turns from a private dinner party to a great lively banquet, with Montaigne as an unwitting master of ceremonies.

Bakewell proceeds to extract Montaigne’s most timeless lessons on the art of living, prefacing them with Gustave Flaubert’s beautiful advice to a friend who was concerned about how to approach Montaigne:

Don’t read him as children do, for amusement, nor as the ambitious do, to be instructed. No, read him in order to live.

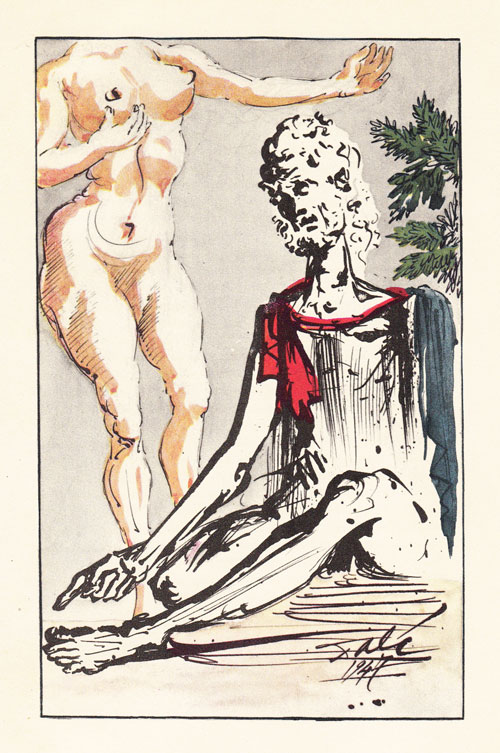

'That To Study Philosophy Is To Learn To Die'

1947 illustration for the essays of Montaigne by Salvador Dalí. Click image for details.

In the first lesson, titled “Don’t Worry About Death,” Bakewall recounts a near-death experience 36-year-old Montaigne had while riding through the woods behind his chateau with some of his estate staff. One of his servants, a muscular giant on a powerful horse, lost control of his animal and “came down like a colossus on the little man and little horse,” thrusting Montaigne onto the ground with enormous force and rendering him unconscious. His companions were eventually able to resuscitate him, but he was throwing up lumps of clotted blood — never an assuring sign — and kept slipping in and out of consciousness, then surrendered to a kind of delirium. Montaigne survived, but the accident profoundly impacted his understanding of life and death. Reflecting on it later, he recorded the peacefulness of that surrender in what he called an exercitation about the experience:

It seemed to me that my life was hanging only by the tip of my lips; I closed my eyes in order, it seemed to me, to help push it out, and took pleasure in growing languid and letting myself go. It was an idea that was only floating on the surface of my soul, as delicate and feeble as all the rest, but in truth not only free from distress but mingled with that sweet feeling that people have who let themselves slide into sleep.

Bakewell draws from this Montaigne’s lesson on relating to death:

Through his exercitation, he had learned not to fear his own nonexistence. Death could have a friendly face, just as the philosophers promised. Montaigne had looked into this face—but he had not stared into it lucidly, as a rational thinker should. Instead of marching forward with eyes open, bearing himself like a soldier, he had floated into death with barely a conscious thought, seduced by it. In dying, he now realized, you do not encounter death at all, for you are gone before it gets there. You die in the same way that you fall asleep: by drifting away. If other people try to pull you back, you hear their voices on “the edges of the soul.” Your existence is attached by a thread; it rests only on the tip of your lips, as he put it. Dying is not an action that can be prepared for. It is an aimless reverie.

This notion of not worrying about death became Montaigne’s most central answer to the question of how to live, recurring again and again in his later work, precipitating a crystalline conviction that living with presence and impermanence is the only true way to live. Bakewell writes:

He tried to import some of death’s delicacy and buoyancy into life. “Bad spots” were everywhere, he wrote in a late essay. We do better to “slide over this world a bit lightly and on the surface.” Through this discovery of gliding and drifting, he lost much of his fear, and at the same time acquired a new sense that life, as it passed through his body — his particular life, Michel de Montaigne’s — was a very interesting subject for investigation. He would go on to attend to sensations and experiences, not for what they were supposed to be, or for what philosophical lessons they might impart, but for the way they actually felt. He would go with the flow.

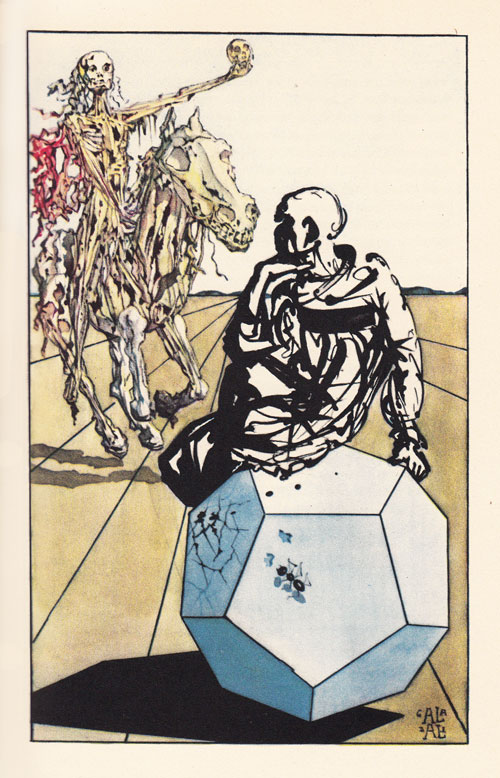

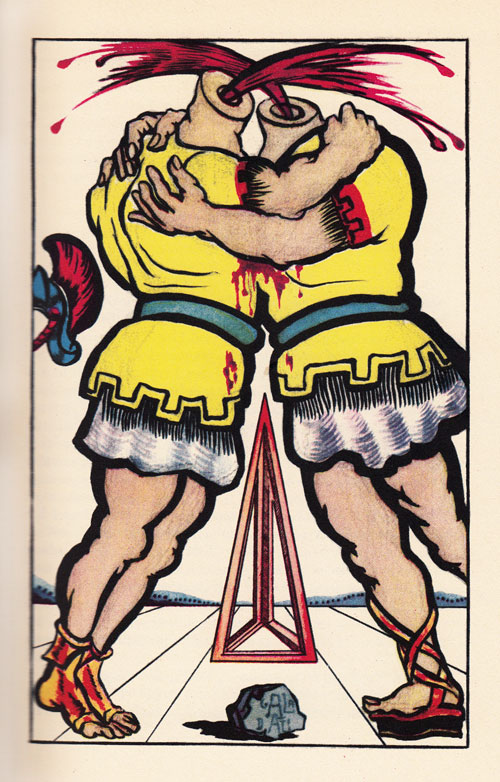

'That To Study Philosophy Is To Learn To Die'

1947 illustration for the essays of Montaigne by Salvador Dalí. Click image for details.

While the riding accident could happen to any young man in the Renaissance, Bakewell points out that what made Montaigne unique was his impulse not only to write about it, but to extract from it a wealth of insight and to let it inform his understanding of a multitude of existential questions. But the accident also taught him something else, something just as valuable yet just as rare among humans — Bakewell titles this lesson “Pay Attention,” which doesn’t come easily to our intentionally discriminating minds. In fact, this yearning to distill the tumultuous bustling of the mind into attentive thought is what drove Montaigne to write in the first place. Blakewell explains:

In a simile borrowed from Virgil, he described his thoughts as resembling the patterns that dance across the ceiling when sunlight reflects off the surface of a water bowl. Just as the tiger-stripes of light lurch about, so an unoccupied mind gyrates unpredictably and brings forth mad, directionless whimsies. It generates fantasies or reveries — two words with less positive associations than they have today, suggesting raving delusions rather than daydreams.His “reverie” in turn gave Montaigne another mad idea: the thought of writing. He called this a reverie too, but it was one that held out the promise of a solution. Finding his mind so filled with “chimeras and fantastic monsters, one after another, without order or purpose,” he decided to write them down, not directly to overcome them, but to inspect their strangeness at his leisure. So he picked up his pen; the first of the Essays was born. … Later, his material grew until it included almost every nuance of emotion or thought he had ever experienced, not least his strange journey in and out of unconsciousness. That, Bakewell argues, is precisely what Montaigne sough — and, ultimately, found — in writing:

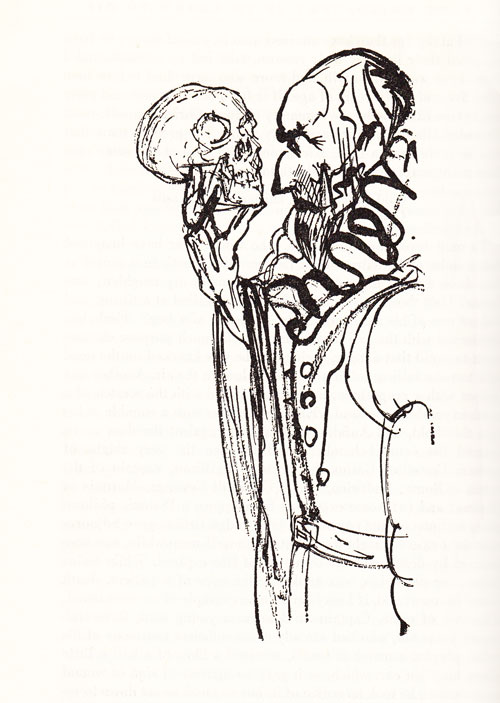

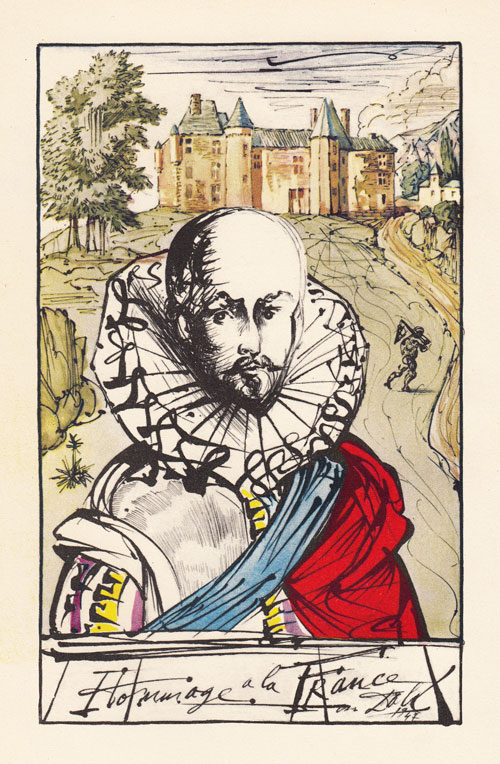

'Upon Some Verses of Virgil'

1947 illustration for the essays of Montaigne by Salvador Dalí. Click image for details.

Writing had got Montaigne through his “mad reveries” crisis; it now taught him to look at the world more closely, and increasingly gave him the habit of describing inward sensations and social encounters with precision. … As Montaigne the man went about his daily life on the estate, Montaigne the writer walked behind him, spying and taking notes.

Indeed, centuries later, Susan Sontag would observe that “a writer … is someone who pays attention to the world.”

Montaigne, like most educated minds of his day, was greatly inspired by the philosophy of the ancients, particularly Seneca, who insisted that salvation is to be found in paying full attention to the natural world, and Plutarch, who advised that the key to achieving peace of mind is in focusing on what is present in front of you in each given moment. But this was far from an easy endeavor — Montaigne himself lamented in one of his essays:

It is a thorny undertaking, and more so than it seems, to follow a movement so wandering as that of our mind, to penetrate the opaque depths of its innermost folds, to pick out and immobilize the innumerable flutterings that agitate it.

More than two centuries before psychology pioneer William James coined the term “stream of consciousness,” Montaigne grew fascinated by it and beheld it regularly. Bakewell writes:

What was unusual in him was his instinct that the observer is as unreliable as the observed. The two kinds of movement interact like variables in a complex mathematical equation, with the result that one can find no secure point from which to measure anything. To try to understand the world is like grasping a cloud of gas, or a liquid, using hands that are themselves made of gas or water, so that they dissolve as you close them.

Indeed, Montaigne advocated for the uncomfortable luxury of changing one’s mind and wrote himself:

If my mind could gain a firm footing, I would not make essays, I would make decisions; but it is always in apprenticeship and on trial.

And therein lies the essence of this particular lesson as well as Montaigne’s greatest legacy, which Bakewell syntheses beautifully:

If you fail to grasp life, it will elude you. If you do grasp it, it will elude you anyway. So you must follow it — and “you must drink quickly as though from a rapid stream that will not always flow.”The trick is to maintain a kind of naive amazement at each instant of experience—but, as Montaigne learned, one of the best techniques for doing this is to write about everything. Simply describing an object on your table, or the view from your window, opens your eyes to how marvelous such ordinary things are. To look inside yourself is to open up an even more fantastical realm.[…]Observing the play of inner states is the writer’s job. Yet this was not a common notion before Montaigne, and his peculiarly restless, free-form way of doing it was entirely unknown.

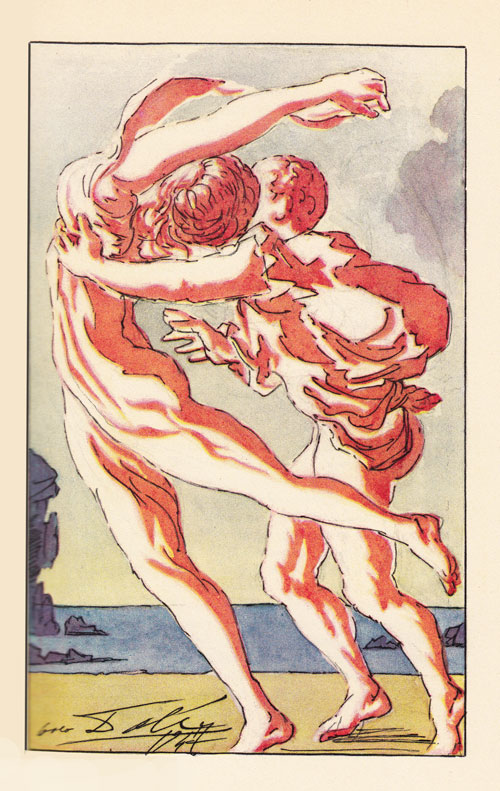

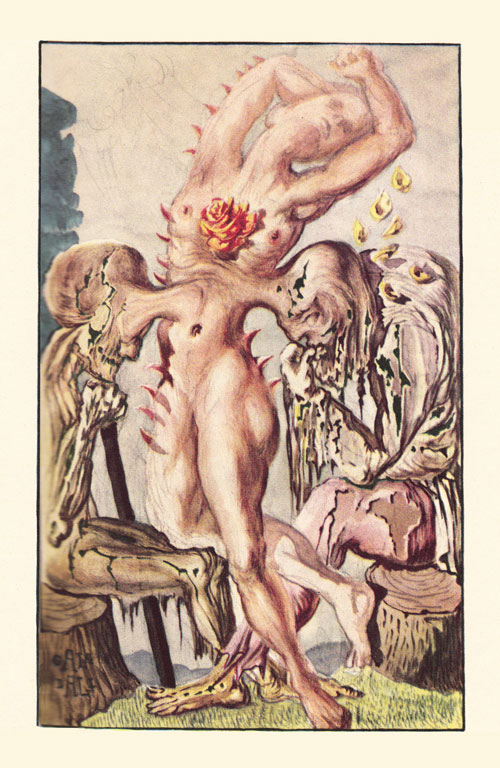

'Of Experience'

1947 illustration for the essays of Montaigne by Salvador Dalí. Click image for details.

But as much as Montaigne taught us about writing, he arguably taught us even more about reading — after all, the two are inextricably intertwined, for a good writer is invariably a good reader. Another insight on the art of living that Bakewell extracts from Montaigne’s writing is to “read a lot.” For Montaigne, books weren’t mere entertainment or education; they were entire experiences, exchanges, bridges to other minds and other epochs. (Cue in my answer to a little girl’s question about why books exist.) Bakewell writes:

What Montaigne looked for in a book, just as people later looked for it in him [was] the feeling of meeting a real person across the centuries. … He took up books as if they were people, and welcomed them into his family.

Montaigne’s greatest lesson, however, is what Bakewell calls the “little tricks” he learned to employ in mastering the art of living. He borrowed some from the ancient Greek philosophers — for instance, the quest for spiritual equilibrium through freedom from anxiety, known as ataraxia. Bakewell brings us back to the art of paying attention:

Ataraxia means equilibrium: the art of maintaining an even keel, so that you neither exult when things go well nor plunge into despair when they go awry. To attain it is to have control over your emotions, so that you are not battered and dragged about by them like a bone fought over by a pack of dogs.[…]Mindful attention is the trick that underlies many of the other tricks. It is a call to attend to the inner world—and thus also to the outer world, for uncontrolled emotion blurs reality as tears blur a view. Anyone who clears their vision and lives in full awareness of the world as it is, Seneca says, can never be bored with life. … For Montaigne, learning to live “appropriately” (à propos) is the “great and glorious masterpiece” of human life.

Paradoxically, however, Montaigne frequently used the opposite of mindful attention — deliberate distraction — to quiet his worries. In his essay “Of Diversion,” he wrote:

A painful notion takes hold of me; I find it quicker to change it than to subdue it. I substitute a contrary one for it, or, if I cannot, at all events a different one. Variation always solaces, dissolves, and dissipates. If I cannot combat it, I escape it; and in fleeing I dodge, I am tricky.

He applied this trick — one of several “side-stepping techniques” he developed over the course of his life — in helping others in distress as well. Bakewell offers an anecdote:

Once, trying to console a woman who was (unlike some widows, he implies) genuinely suffering grief for her dead husband, he first considered the more usual philosophical methods: reminding her that nothing can be gained from lamentation, or persuading her that she might never have met her husband anyway. But he settled on a different trick: “very gently deflecting our talk and diverting it bit by bit to subjects nearby, then a little more remote.” The widow seemed to pay little attention at first, but in the end the other subjects caught her interest. Thus, without her realizing what was happening, he wrote, “I imperceptibly stole away from her this painful thought and kept her in good spirits and entirely soothed for as long as I was there.” He admitted that this did not go to the root of her grief, but it got her through an immediate crisis, and presumably allowed time to begin its own natural work.[…]Distraction works well precisely because it accords with how humans are made: “Our thoughts are always elsewhere.” It is only natural for us to lose focus, to slip away from both pains and pleasures, “barely brushing the crust” of them. All we need do is let ourselves be as we are.

'That Fortune Is Oftentimes Observed to Act by the Rules of Reason'

1947 illustration for the essays of Montaigne by Salvador Dalí. Click image for details.

Another lesson from Montaigne has to do with relinquishing control — something particularly prescient in the context of publishing, remix culture, and peer-to-peer sharing. Working long before the establishment of copyright law, Montaigne had no illusions about creative ownership. Bakewell writes:

Montaigne knew very well that, the minute you publish a book, you lose control of it. Other people can do what they like: they can edit it into strange forms, or impose interpretations upon it that you would never have dreamed of. Even an unpublished manuscript can get out of hand.

In fact, in his time, shortly after the golden age of florilegia, copying was a legitimate and very common literary technique. Montaigne related to this inevitable loss of control with acceptance rather than vexation (or its contemporary equivalent, the legal cease-and-desist) — and this was one of his greatest “tricks” of living. Bakewell relays this beautifully, with a brilliantly placed Nina Simone reference:

There can be no really ambitious writing without an acceptance that other people will do what they like with your work, and change it almost beyond recognition. Montaigne accepted this principle in art, as he did in life. He even enjoyed it. People form strange ideas of you; they adapt you to their own purposes. By going with the flow and relinquishing control of the process, you gain all the benefits of the old Hellenistic trick of amor fati: the cheerful acceptance of whatever happens. In Montaigne’s case, amor fati was one of the answers to the general question of how to live, and as it happened it also opened the way to his literary immortality. What he left behind was all the better for being imperfect, ambiguous, inadequate, and vulnerable to distortion. “Oh Lord,” one might imagine Montaigne exclaiming, “by all means let me be misunderstood.”

And in some strange and beautiful symmetry, this is all exactly as it should be and as it has always been. Much like Montaigne himself remixed the ideas of the Greek philosophers about how to live, so we too, today, remix his. It is precisely in this vulnerability to distortion that we find true literary immortality — by plunging into the cascade of ideas across the centuries and emerging, drenched to the bone, with our own. Even young Virginia Woolf knew this when shemarveled at the chain of minds threading the world together.

Ultimately, what made Montaigne’s mind unique was his ability to find in any ordinary life, any ordinary experience, all that is worth knowing about life. He wrote:

I set forth a humble and inglorious life; that does not matter. You can tie up all moral philosophy with a common and private life just as well as with a life of richer stuff. Indeed, that is just what a common and private life is: a life of the richest stuff imaginable.

Bakewell beholds this singular gift:

Indeed, that is just what a common and private life is: a life of the richest stuff imaginable.

Montaigne’s greatest gift to us, however, is his unflinching acceptance of imperfection — for, without it, we are bound to remain forever oppressed by our perfectionism. Much of this he drew from the fact — and the act — of aging, but not in the way we might expect. Bakewell writes:

It was not that age automatically conferred wisdom. On the contrary, he thought the old were more given to vanities and imperfections than the young. They were inclined to “a silly and decrepit pride, a tedious prattle, prickly and unsociable humors, superstition, and a ridiculous concern for riches.” But this was the twist, for it was in the adjustment to such flaws that the value of aging lay. Old age provides an opportunity to recognize one’s fallibility in a way youth usually finds difficult. Seeing one’s decline written on body and mind, one accepts that one is limited and human. By understanding that age does not make one wise, one attains a kind of wisdom after all.Learning to live, in the end, is learning to live with imperfection in this way, and even to embrace it.

Montaigne put it best himself:

Our being is cemented with sickly qualities … Whoever should remove the seeds of these qualities from man would destroy the fundamental conditions of our life.

He also, despite the magnificently winding road of his existential meditations, gave us the straightforward answer on how to live:

Life should be an aim unto itself, a purpose unto itself.

How to Live, which contains a total of twenty lessons drawn from Montaigne, is a must-read in its entirety. Complement it with Roman Krznaric’s excellent and more recent How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life, then revisit Alan Watts on how to live with presence.

No comments:

Post a Comment