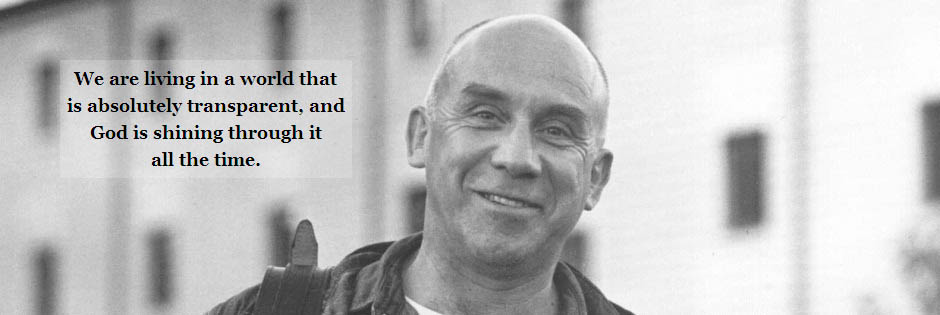

Thomas Merton, Trappist Monk and Priest

"The terrible thing about our time is precisely the ease with which theories can be put into practice. The more perfect, the more idealistic the theories, the more dreadful is their realization. We are at last beginning to rediscover what perhaps men knew better in very ancient times, in primitive times before utopias were thought of: that liberty is bound up with imperfection, and that limitations, imperfections, errors are not only unavoidable but also salutary. The best is not the ideal. Where what is theoretically best is imposed on everyone as the norm, then there is no longer any room even to be good. The best, imposed as a norm, becomes evil.” Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Thomas Merton (Doubleday and Co., Garden City, New York, 1968)

“The dread of being open to the ideas of others generally comes from our hidden insecurity about our own convictions. We fear that we may be “converted” – or perverted – by a pernicious doctrine. On the other hand, if we are mature and objective in our open-mindedness, we may find that viewing things from a basically different perspective – that of our adversary – we discover our own truth in a new light and are able to understand our own ideal more realistically. Our willingness to take an alternative approach to a problem will perhaps relax the obsessive fixation of the adversary on his view, which he believes is the only reasonable possibility and which he is determined to impose on everyone else by coercion…This mission of Christian humility in social life is not merely to edify, but to keep minds open to many alternatives. The rigidity of a certain type of Christian thought has seriously impaired this capacity, which nonviolence must recover.”

Passion For Peace by Thomas Merton, edited by William H. Shannon (New York: Crossroad Publishing 1995), pgs. 255-256

“In our age everything has to be a ‘problem.’ Ours is a time of anxiety because we have willed it to be so. Our anxiety is not imposed on us by force from outside. We impose it on our world and upon one another from within ourselves. Sanctity in such an age means, no doubt, traveling from the area of anxiety to the area in which there is no anxiety or perhaps it may mean learning, from God, to be without anxiety in the midst of anxiety. Fundamentally, as Max Picard points out, it probably comes to this: living in a silence which so reconciles the contradictions within us that, although they remain within us, they cease to be a problem. (of World of Silence, P. 66-67.)

“In our age everything has to be a ‘problem.’ Ours is a time of anxiety because we have willed it to be so. Our anxiety is not imposed on us by force from outside. We impose it on our world and upon one another from within ourselves. Sanctity in such an age means, no doubt, traveling from the area of anxiety to the area in which there is no anxiety or perhaps it may mean learning, from God, to be without anxiety in the midst of anxiety. Fundamentally, as Max Picard points out, it probably comes to this: living in a silence which so reconciles the contradictions within us that, although they remain within us, they cease to be a problem. (of World of Silence, P. 66-67.)

One of the most disturbing facts that came out in the [Adolf] Eichmann trial was that a psychiatrist examined him and pronounced him perfectly sane. I do not doubt it at all, and that is precisely why I find it disturbing. . . The sanity of Eichmann is disturbing. We equate sanity with a sense of justice, with humaneness, with prudence, with the capacity to love and understand other people. We rely on the sane people of the world to preserve it from barbarism, madness, destruction. And now it begins to dawn on us that it is precisely the sane ones who are the most dangerous. It is the sane ones, the well-adapted ones, who can without qualms and without nausea aim the missiles and press the buttons that will initiate the great festival of destruction that they, the sane ones, have prepared. What makes us so sure, after all, that the danger comes from a psychotic getting into a position to fire the first shot in a nuclear war? Psychotics will be suspect. The sane ones will keep them far from the button. No one suspects the sane, and the sane ones will have perfectly good reasons, logical, well-adjusted reasons, for firing the shot. They will be obeying sane orders that have come sanely down the chain of command. And because of their sanity they will have no qualms at all. When the missiles take off, then, it will be no mistake.

Thomas Merton. "A Devout Meditation in Memory of Adolf Eichmann" in Raids on the Unspeakable. New York: New Directions Publishing Co., 1964

You are fed up with words and I don’t blame you. I am nauseated by them

sometimes. I am also, to tell the truth, nauseated by ideals and with

causes. This sounds like heresy, but I think you will understand what I

mean. It is so easy to get engrossed with ideas and slogans and myths

that in the end one is left holding the bag, empty, with no trace of

meaning left in it. And then the temptation is to yell louder than ever

in order to make meaning be there again by magic...

"Authority has simply been abused too long in the Catholic church,

and for many people it just becomes utterly stupid and intolerable

to have to put up with the kind of jackassing around that is imposed

in God's name. It is an insult to God himself and in the end it can

only discredit all idea of authority and obedience. There comes

a point where they simply forfeit the right to be listened to."

Thomas Merton in a letter to W. H. Ferry.

Fated January 19, 1967, 23 months before Merton's death

Thomas Merton was once asked to write a chapter for a book entitled

"Secrets of Success." He replied: "If it so happened that I had once

written a best-seller, this was a pure accident, due to inattention and

naivete, and I would take very good care never to do the same again.

If I had a message for my contemporaries, I said, it was surely this: Be

anything you like, be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and

form, but at all costs avoid one thing: success."

It seems to me there are very dangerous ambiguities about our democracy

in its actual present condition. I wonder to what extent our ideals are now

a front for organized selfishness and irresponsibility. If our affluent society ever

breaks down and the facade is taken away, what are we going to have left?

[A] faith that is afraid of other people is no faith at all. A faith that supports itself by condemning others is itself condemned by the Gospel.

The Christian is one whose life has sprung from a particular spiritual

seed: the blood of martyrs, who, without offering forcible resistance,

laid down their lives rather than submit to unjust laws... That is to say,

the Christian is bound, like the martyrs, to obey God rather than the

state whenever the state tries to usurp powers that do not and cannot

belong to it.

Do not depend on the hope of results. When you are doing the sort of work

you have taken on, essentially an apostolic work, you may have to face the

fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no

result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you

get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the

results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself.

And there too a great deal has to be gone through, as gradually you

struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people.

The range tends to narrow down, but it gets much more real. In the end,

it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.

This change is a recovery of that which is deepest, most original, most

personal in ourselves. To be born again is not to become somebody else,

but to become ourselves.

We become contemplatives when God discovers Himself in us.

The night became very dark. The rain surrounded the whole cabin with its

enormous virginal myth, a whole world of meaning, of secrecy, of silence,

of rumor. Think of it: all that speech pouring down, selling nothing,

judging nobody, drenching the thick mulch of dead leaves, soaking the

trees, filling the gullies and crannies of the wood with water, washing

out the places where men have stripped the hillside. What a thing it is

to sit absolutely alone in the forest at night, cherished by this

wonderful, unintelligent perfectly innocent speech, the most comforting

speech in the world, the talk that rain makes by itself all over the

ridges, and the talk of the watercourses everywhere in the hollows.

Nobody started it, nobody is going to stop it. It will talk as

long as it wants, the rain. As long as it talks I am going to listen.

The real function of discipline is not to provide us with maps, but to

sharpen our own sense of direction so that when we really get going we can

travel without maps.

A demonic existence is one which insistently diagnoses what it cannot

cure, what it has no desire to cure, what it seeks to bring to full

potency, in order that it may cause the death of its victim.

How many there must be who have smothered the first sparks of

contemplation by piling wood on the fire before it was well lit.

“Living with other people and learning to lose ourselves in the understanding of their weakness and deficiencies can help us to become true contemplatives. For there is no better means of getting rid of the rigidity and harshness and coarseness of our ingrained egoism, which is the one insuperable obstacle to the infused light and action of the Spirit of God. Even the courageous acceptance of interior trials in utter solitude cannot altogether compensate for the work of purification accomplished in us by patience and humility in loving other men and sympathizing with their most unreasonable needs and demands.” Seeds of Destruction

“The dread of being open to the ideas of others generally comes from our hidden insecurity about our own convictions. We fear that we may be “converted” – or perverted – by a pernicious doctrine. On the other hand, if we are mature and objective in our open-mindedness, we may find that viewing things from a basically different perspective – that of our adversary – we discover our own truth in a new light and are able to understand our own ideal more realistically. Our willingness to take an alternative approach to a problem will perhaps relax the obsessive fixation of the adversary on his view, which he believes is the only reasonable possibility and which he is determined to impose on everyone else by coercion…This mission of Christian humility in social life is not merely to edify, but to keep minds open to many alternatives. The rigidity of a certain type of Christian thought has seriously impaired this capacity, which nonviolence must recover.”

Passion For Peace by Thomas Merton, edited by William H. Shannon (New York: Crossroad Publishing 1995), pgs. 255-256

“The life of contemplation in action and purity of heart is, then, a life of great simplicity and inner liberty. One is not seeking anything special or demanding any particular satisfaction. One is content with what is. One does what is to be done, and the more concrete it is, the better. One is not worried about the results of what is done. One is content to have good motives and not too anxious about making mistakes. In this way one can swim with the living stream of life and remain at every moment in contact with God, in the hiddenness and ordinariness of the present moment with its obvious task.”

The Inner Experience by Thomas Merton Edited by William H. Shannon (New York: HaperCollins 2004)]

“Where there is a deep, simple, all-embracing love of man, of the created world of living and inanimate things, then there will be respect for life, for freedom, for truth, for justice and there will be humble love of God. But where there is no love of man, no love of life, then make all the laws you want, all the edicts and treaties, issue all the anathemas; set up all the safeguards and inspections, fill the air with spying satellites, and hang cameras on the moon. As long as you see your fellow man being essentially to be feared, mistrusted, hated, and destroyed, there cannot be peace on earth. And who knows if fear alone will suffice to prevent a war of total destruction?”

Seeds of Destruction by Thomas Merton (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1964), p.183

“Inexorably life moves on toward crisis and mystery.

One must not be too quickly preoccupied with professing definitively what is true and what is false. Not that true and false do not matter. But if at every instant one wants to grasp the whole and perfect truth of a situation, particularly a concrete and limited situation in history or in politics, one only deceives and blinds himself. Such judgments are only rarely and fleetingly possible, and sometimes, when we think we see what is most significant, it has very little meaning at all.

So it is possible that the moment of my death may turn out to be, from a human and ‘economic’ point of view, the most meaningless of all.

Meanwhile, I do not have to stop the flow of events in order to understand them. On the contrary, I must move with them or else what I think I understand will be no more than an image in my own mind.”

August 16 and 19, 1961, IV. 152-153

A Year with Thomas Merton, Daily Meditations from His Journals, selected and edited by Jonathan Montaldo

“Fickleness and indecision are signs of self-love.

If you can never make up your mind what God wills for you, but are always veering from one opinion to another, from one practice to another, from one method to another, it may be an indication that you are trying to get around God’s will and do your own with a quiet conscience.

As soon as God gets you in one monastery you want to be in another.

As soon as you taste one way of prayer, you want to try another. You are always making resolutions and breaking them by counter-resolutions. You ask your confessor and do not remember the answers. Before you finish one book you begin another, and with every book you read you change the whole plan of your interior life.

Soon you will have no interior life at all. Your whole existence will be a patchwork of confused desires and daydreams and velleities in which you do nothing except defeat the work of grace: for all this is an elaborate subconscious device of your nature to resist God, Whose work in your soul demands the sacrifice of all that you desire and delight in, and, indeed, of all that you are.

So keep still, and let Him do some work.

This is what it means to renounce not only pleasures and possessions, but even your own self.”

New Seeds of Contemplation by Thomas Merton,

“…Grant us prudence in proportion to our power,

Wisdom in proportion to our science,

Humaneness in proportion to our wealth and might.

And bless our earnest will to help all races and peoples to travel, in friendship with us,

Along the road to justice, liberty and lasting peace:

But grant us above all to see that our ways are not necessarily your ways,

That we cannot fully penetrate the mystery of your designs

And that the very storm of power now raging on this earth

Reveals your hidden will and your inscrutable decision.

Grant us to see your face in the lightning of this cosmic storm,

O God of holiness, merciful to men:

Grant us to seek peace where it is truly found!

In your will, O God, is our peace!

Amen”

Passion for Peace by Thomas Merton, Edited by William H. Shannon, Crossroad Publishing Company, New York, NY, 1995. Appendix: Merton’s Prayer for Peace, pages 328-329.

“The shallow ‘ I ‘ of individualism can be possessed, developed, cultivated, pandered to, satisfied: it is the center of all our strivings for gain and for satisfaction, whether material or spiritual. But the deep ‘ I ‘ of the spirit, of solitude and of love, cannot be ‘had,’ possessed, developed, perfected. It can only be, and act according to deep inner laws which are not of man’s contriving, but which come from God. They are the Laws of the Spirit, who, like the wind, blows where He wills. This inner ‘ I, ‘ who is always alone, is always universal: for in this inmost ‘ I ‘ my own solitude meets the solitude of every other man and the solitude of God." Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1960.

“There is another self, a true self, who comes to full maturity in emptiness and solitude – and who can of course, begin to appear and grow in the valid, sacrificial and creative self-dedication that belong to a genuine social existence. But note that even this social maturing of love implies at the same time the growth of a certain inner solitude. Without solitude of some sort there is and can be no maturity. Unless one becomes empty and alone, he cannot give himself in love because he does not possess the deep self which is the only gift worthy of love. And this deep self, we immediately add, cannot be possessed. My deep self in not ‘something’ which I acquire, or to which I ‘attain’ after a long struggle. It is not mine, and cannot become mine. It is no ‘thing’ – no object. It is ‘I’. ”

Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1960.

“There is a stage in the spiritual life in which we find God in ourselves – this presence is a created effect of His love. It is a gift of His, to us. It remains in us. All the gifts of God are good. But if we rest in them, rather than in Him, they lose their goodness for us. So with this gift also.

When the right time comes for us to go on to other things, God withdraws the sense of His presence, in order to strengthen our faith. After that it is useless to seek Him through the medium of any psychological effect. Useless to look for any sense of Him in our hearts. The time has come when we must go out of ourselves and above ourselves and find Him no longer within us but outside us and above us…in service of our brothers.”

Thoughts in Solitude by Thomas Merton. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Publishers, New York, NY. 1958 Page 54

Contradictions have always existed in the soul of man. But it is only when we prefer analysis to silence that they become a constant and insoluble problem. We are not meant to resolve all contradictions but to live with them and rise above them and see them in the light of exterior and objective values which make them trivial by comparison.”

Thoughts in Solitude by Thomas Merton. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Publishers, New York, NY. 1958

“The fact that our being necessarily demands to be expressed in action should not lead us to believe that as soon as we stop acting we cease to exist. We do not live merely in order to ‘do something’ – no matter what. Activity is just one of the normal expressions of life, and the life it expresses is all the more perfect when it sustains itself with an ordered economy of action. This order demands a wise alternation of activity and rest. We do not live more fully merely by doing more, seeing more, tasting more, and experiencing more than we ever have before. On the contrary, some of us need to discover that we will not begin to live more fully until we have the courage to do and see and taste and experience much less than usual.” No Man is an Island by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1955 Page 122.

“Those who love their own noise are impatient of everything else. They constantly defile the silence of the forests and the mountains and the sea. They bore through silent nature in every direction with their machines, for fear that the calm world might accuse them of their own emptiness. The urgency of their swift movement seems to ignore the tranquility of nature by pretending to have a purpose. The loud plane seems for a moment to deny the reality of the clouds and of the sky, by its direction, its noise, and its pretended strength. The silence of the sky remains when the plane has gone. The tranquility of the clouds will remain when the plane has fallen apart. It is the silence of the world that is real. Our noise, our business, our purposes, and all our fatuous statements about our purposes, our business, and our noise: these are the illusion.”

From No Man is an Island by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1955 Page 257.

“Augustine, for all his pessimism about human nature, did not foresee the logical results of his thought, and in the original context, his “wars of mercy” to defend civilized order make a certain amount of sense. Always his idea is that the Church and the Christians, whatever they may do, are aiming at ultimate peace. The deficiency of Augustinian thought lies therefore not in the good intentions it prescribes but in an excessive naïveté with regard to the good that can be attained by violent means which cannot help but call forth all that is worst in man. And so, alas, for centuries we have heard kings, princes, bishops, priests, ministers, and the Lord alone knows what variety of unctuous beadles and sacrists, earnestly urging all men to take up arms out of love and mercifully slay their enemies (including other Christians)...”

The Nonviolent Alternative by Thomas Merton. Farrar, Straus, Giroux, New York, NY. 1980 Page 45.

“The silence of the tongue and of the imagination dissolves the barrier between ourselves and the peace of things that exist only for God and not for themselves. But the silence of all inordinate desire dissolves the barrier between ourselves and God. Then we come to live in Him alone.”

No Man is an Island by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1955

“Perhaps peace is not, after all, something you work for, or ‘fight for.’ It is indeed ‘fighting for peace’ that starts all the wars. What, after all, are the pretexts of all these Cold War crises, but ‘fighting for peace?’ Peace is something you have or do not have. If you are yourself at peace, then there is at least some peace in the world. Then share your peace with everyone, and everyone will be at peace.”

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander by Thomas Merton. Image Books. A Division of Doubleday & Company Inc., Garden City, NY. 1968 Pages 200.

“Even though we have the power to destroy the whole world, life is stronger than the death instinct and love is stronger than hate. It does not make logical sense to be too hopeful, but once again this is not a question of logic and one does not look for signs of hope in the newspapers or the pronouncements of world leaders (in these there is seldom anything really hopeful, and that which is supposed to be most encouraging is usually so transparently hopeless that it moves one closer to despair). Because there is love in the world, and because Christ has taken our nature to Himself, there remains always the hope that man will finally, after many mistakes and even disasters, learn to disarm and to make peace, recognizing that he must live at peace with his brother. Yet never have we been less disposed to do this.”

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander by Thomas Merton. Image Books. A Division of Doubleday & Company Inc., Garden City, NY. 1968 Pages 214.

“This poem was composed in the days immediately following Merton’s receipt of a telegram on Easter Monday of 1943 reporting his brother, John Paul, missing in action. His bomber aircraft had malfunctioned and crashed into the English Channel, where he died of a broken back and dehydration before the rest of the crew was rescued. He was buried at sea.”

For My Brother: Reported Missing in Action, 1943

Sweet brother, if I do not sleep

My eyes are flowers for your tomb;

And if I cannot eat my bread,

My fasts shall live like willows where you died.

If in the heat I find no water for my thirst,

My thirst shall turn to springs for you, poor traveler.

Where, in what desolate and smokey country,

Lies your poor body, lost and dead?

And in what landscape of disaster

Has your unhappy spirit lost its road?

Come, in my labor find a resting place

And in my sorrows lay your head,

Or rather take my life and blood

And buy yourself a better bed –

Or take my breath and take my death

And buy yourself a better rest.

When all the men of war are shot

And flags have fallen into dust,

Your cross and mine shall tell men still

Christ died on each, for both of us.

For in the wreckage of your April Christ lies slain,

And Christ weeps in the ruins of my spring:

The money of Whose tears shall fall

Into your weak and friendless hand,

And buy you back to your own land;

The silence of Whose tears shall fall

Like bells upon your alien tomb.

Hear them and come: they call you home.

In the Dark Before Dawn, New Selected Poems of Thomas Merton prefaced by Kathleen Norris, Edited by Lynn R. Szabo. New Directions Publishing Company, NY, NY. 2005 Pages 181, 244

“Man’s greatest dignity, his most essential and peculiar power, the most intimate secret of his humanity is his capacity to love. This power in the depths of man’s soul stamps him in the image and likeness of God. Unlike other creatures in the world around us, we have access to the inmost sanctuary of our own being. We can enter into ourselves as into temples of freedom and of light. We can open the eyes of our heart and stand face to face with God our Father. We can speak to Him and hear Him answer. He tells us not merely that we are called to be men and to rule our earth, but that we have an even more exalted vocation than this. We are His children.”

Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, CA, 1960. Page 98.

“Man’s unhappiness seems to have grown in proportion to his power over the exterior world. And anyone who claims to have a glib explanation of this fact had better take care that he too is not the victim of a delusion. For after all, this should not necessarily be so. God made man the ruler of the earth, and all science worthy of the name participates in some way in the wisdom and providence of the Creator. But the trouble is that unless the works of man’s wisdom, knowledge and power participate in the merciful love of God, they are without real value for the world and for man. They do nothing to make man happy and they do not manifest in the world the glory of God.”

Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, CA, 1960. Page 98.

“I have a profound mistrust of all obligatory answers. The great problem of our time is not to formulate clear answers to neat theoretical questions… The way to find the real ‘world’ is not merely to measure and observe what is outside us, but to discover our own inner ground. For that is where the world is, first of all: in my deepest self. But there I find the world to be quite different from the ‘obligatory answers.’ This ‘ground,’ this ‘world’ where I am mysteriously present at once to my own self and to the freedoms of all other men, is not a visible objective and determined structure with fixed laws and demands. It is a living and self-creating mystery of which I am myself a part, to which I am myself my own unique door. When I find the world in my own ground, it is impossible for me to be alienated by it.”

Contemplation in a World of Action by Thomas Merton. Image Books, Garden City, NY, 1973. A Division of Doubleday & Company. Pages 168 & 170.

Heavenliness in the Nature of Things:

“Real Spring weather—these are the precise days when everything changes. All the trees are fast beginning to be in leaf, and the first green freshness of a new summer is all over the hills. Irreplaceable purity of these days chosen by God as His sign! Mixture of heavenliness and anguish. Seeing ‘heavenliness’ suddenly, for instance, in the pure white of mature dogwood blossoms against the dark evergreens in the cloudy garden. ‘Heavenliness’ too of the song of the unknown bird that is perhaps here only for these days, passing through, a lovely, deep, simple song. Seized by this ‘heavenliness’ as if I were a child—a child’s mind I have never done anything to deserve to have and which is my own part in the heavenly spring. Not of this world, or of my making. Born partly of physical anguish (which is really not there, though. It goes quickly). Sense that the ‘heavenliness’ is the real nature of things, not their nature, but the fact they are a gift of love and of freedom.”

A Year with Thomas Merton: Daily Meditations from His Journals by Thomas Merton, selected and edited Jonathan Montaldo. HarperSanFrancisco, New York, NY, 2004, p 120.

"A humble man can do great things with an uncommon perfection because he is no longer concerned about incidentals, like his own interests and his own reputation, and therefore he no longer needs to waste his efforts in defending them.

For a humble man is not afraid of failure. In fact, he is not afraid of anything, even of himself, since perfect humility implies perfect confidence in the power of God before Whom no other power has any meaning and for Whom there is no such thing as an obstacle.

Humility is the surest sign of strength.”

Seeds by Thomas Merton, selected and edited Robert Inchausti. Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boston, MA, 2002, p 112. Originally published in New Seeds of Contemplation. New York: New Directions, 1972, p 190.

"There is in all visible things an invisible fecundity, a dimmed light, a meek namelessness, a hidden wholeness. This mysterious Unity and Integrity is Wisdom, the Mother of all, Natura Naturans. There is in all things an inexhaustible sweetness and purity, a silence that is a fount of action and joy. It rises up in wordless gentleness and flows out to me from the unseen roots of all created being, welcoming me tenderly, saluting me with indescribable humility. This is at once my own being, my own nature, and the Gift of my Creator’s Thought and Art within me, speaking as Hagia Sophia, speaking as my sister, Wisdom.

I am awakened, I am born again at the voice of this my Sister, sent to me from the depths of the divine fecundity.”

From when the trees say nothing by Thomas Merton, edited by Kathleen Deignan. Notre Dame, Indiana: Sorin Books, 2003, p 179. Originally published in Emblems of a Season of Fury. Norfolk, CT: J. Laughlin, 1963

"Basically our first duty today is to human truth in its existential reality, and this sooner or later brings us into confrontation with system and power which seek to overwhelm truth for the sake of particular interests, perhaps rationalized as ideals. Sooner or later the human duty presents itself in a form of crisis that cannot be evaded. At such a time it is very good, almost essential, to have at one’s side others with a similar determination, and one can then be guided by a common inspiration and a communion in truth. Here true strength can be found. A completely isolated witness is much more difficult and dangerous. In the end that too may become necessary. But in any case we know that our only ultimate strength is in the Lord and His Spirit, and faith must make us depend entirely on His will and providence. One must then truly be detached and free in order not to be held and impeded by anything secondary or irrelevant. Which is another way of saying that poverty also is our strength.”

Seeds by Thomas Merton, selected and edited by Robert Inchausti (Shambhala, Boston & London, 2002), P 59.

Originally published in The Courage for Truth: The Letters of Thomas Merton to Writers, selected and edited by Christine M. Bochen (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1993), P 159.

"I come into solitude to die and love. I come here to be created by the Spirit in Christ.

I am called here to grow. ‘Death’ is a critical point of growth, or transition to a new mode of being; to a maturity and fruitfulness that I do not know (they are in Christ and in His kingdom). The child in the womb does not know what will come after birth. He must be born in order to live. I am here to learn to face death as my birth.”

December 1, 1965, V.333-34 A Year with Thomas Merton, Daily Meditations from His Journals, selected and edited by Jonathan Montaldo (HarperSanFrancisco, A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers, New York, 2004)

The shallow ‘ I ‘ of individualism can be possessed, developed, cultivated, pandered to, satisfied: it is the center of all our strivings for gain and for satisfaction, whether material or spiritual. But the deep ‘ I ‘ of the spirit, of solitude and of love, cannot be ‘had,’ possessed, developed, perfected. It can only be, and act according to deep inner laws which are not of man’s contriving, but which come from God. They are the Laws of the Spirit, who, like the wind, blows where He wills. This inner ‘ I, ‘ who is always alone, is always universal: for in this inmost ‘ I ‘ my own solitude meets the solitude of every other man and the solitude of God.

Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1960.

“There is another self, a true self, who comes to full maturity in emptiness and solitude – and who can of course, begin to appear and grow in the valid, sacrificial and creative self-dedication that belong to a genuine social existence. But note that even this social maturing of love implies at the same time the growth of a certain inner solitude.

Without solitude of some sort there is and can be no maturity. Unless one becomes empty and alone, he cannot give himself in love because he does not possess the deep self which is the only gift worthy of love. And this deep self, we immediately add, cannot be possessed. My deep self in not ‘something’ which I acquire, or to which I ‘attain’ after a long struggle. It is not mine, and cannot become mine. It is no ‘thing’ – no object. It is ‘I.’ Disputed Questions by Thomas Merton. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, NY. 1960.

“There is a stage in the spiritual life in which we find God in ourselves – this presence is a created effect of His love. It is a gift of His, to us. It remains in us. All the gifts of God are good. But if we rest in them, rather than in Him, they lose their goodness for us. So with this gift also.

When the right time comes for us to go on to other things, God withdraws the sense of His presence, in order to strengthen our faith. After that it is useless to seek Him through the medium of any psychological effect. Useless to look for any sense of Him in our hearts. The time has come when we must go out of ourselves and above ourselves and find Him no longer within us but outside us and above us…in service of our brothers.”

Thoughts in Solitude by Thomas Merton. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Publishers, New York, NY. 1958 Page 54.

“In our age everything has to be a ‘problem.’ Ours is a time of anxiety because we have willed it to be so. Our anxiety is not imposed on us by force from outside. We impose it on our world and upon one another from within ourselves.

Sanctity in such an age means, no doubt, traveling from the area of anxiety to the area in which there is no anxiety or perhaps it may mean learning, from God, to be without anxiety in the midst of anxiety.

Fundamentally, as Max Picard points out, it probably comes to this: living in a silence which so reconciles the contradictions within us that, although they remain within us, they cease to be a problem. (World of Silence)

Contradictions have always existed in the soul of man. But it is only when we prefer analysis to silence that they become a constant and insoluble problem. We are not meant to resolve all contradictions but to live with them and rise above them and see them in the light of exterior and objective values which make them trivial by comparison.”

Thoughts in Solitude by Thomas Merton. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, Publishers, New York, NY. 1958

"But now the power of Easter has burst upon us with the resurrection of Christ. Now we find in ourselves a strength which is not our own, and which is freely given to us whenever we need it, raising us above the Law, giving us a new law which is hidden in Christ: the law of His merciful love for us. Now we no longer strive to be good because we have to, because it is a duty, but because our joy is to please Him who has given all His love to us! Now our life is full of meaning!

… To understand Easter and live it, we must renounce our dread of newness and of freedom!”

Seasons of Celebration by Thomas Merton (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 1986), Pages 145-46.

"We cannot avoid missing the point of almost everything we do. But what of it? Life is not a matter of getting something out of everything. Life itself is imperfect. All created beings begin to die as soon as they begin to live, and no one expects any one of them to become absolutely perfect, still less to stay that way. Each individual thing is only a sketch of the specific perfection planned for its kind. Why should we ask it to be anything more?”

No Man is an Island (New York: Harcourt Brace Javonovich, 1983), PP 128

"The worst thing that can happen to a person who is already divided up into a dozen different compartments is to seal off yet another compartment and tell him that this one is more important than all the others, and that he must henceforth exercise a special care in keeping it separate from them. That is what tends to happen when contemplation is unwisely thrust without warning upon the bewilderment and distraction of Western man. The Eastern traditions have the advantage of disposing the person more naturally for contemplation.

The first thing that you have to do, before you start thinking about such a thing as contemplation, is to try to recover your basic natural unity, to reintegrate your compartmentalized being into a coordinated and simple whole, and learn to live as a unified human person. This means that you have to bring back together the fragments of your distracted existence so that when you say ‘I’ there is really someone present to support the pronoun you have uttered.”

Seeds selected and edited by Robert Inchausti (Boston, MA, Shambhala Publications, Inc, 2002, pages 84, 85).

"Douglas Steere remarks very perceptively that there is a pervasive form of contemporary violence to which the idealist fighting for peace by nonviolent methods most easily succumbs: activism and overwork. The rush and pressure of modern life are a form, perhaps the most common form, of its innate violence. To allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone in everything is to succumb to violence. More than that, it is cooperation in violence. The frenzy of the activist neutralizes his work for peace. It destroys his own inner capacity for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of his own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.”

Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander by Thomas Merton (Doubleday and Co., Garden City, New York, 1968)

"The terrible thing about our time is precisely the ease with which theories can be put into practice. The more perfect, the more idealistic the theories, the more dreadful is their realization. We are at last beginning to rediscover what perhaps men knew better in very ancient times, in primitive times before utopias were thought of: that liberty is bound up with imperfection, and that limitations, imperfections, errors are not only unavoidable but also salutary. The best is not the ideal. Where what is theoretically best is imposed on everyone as the norm, then there is no longer any room even to be good. The best, imposed as a norm, becomes evil.” Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Thomas Merton (Doubleday and Co., Garden City, New York, 1968)

"… Finally, about being united with God’s will: I don’t mean that you should specially formulate this in words frequently but rather just develop a habitual awareness and conviction that you are completely in His hands and His love is taking care of you in everything, that you need have no special worries about anything, past present or future, as long as you are sincerely trying to do what He seems to ask of you. And of course by that I mean simply what is called for by the obvious needs of the moment, duties of state, people you meet, events to cope with, sicknesses, mistakes, and so on. ‘When hungry eat, when tired sleep.’

The Hidden Ground of Love by Thomas Merton (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1985), page 526.

Hoping for Results? Facing Despair - and False Notions of Success

In this letter to a friend, Thomas Merton addresses a frustration every person has known, or will one day know: the sinking feeling that one's efforts (in whatever arena they are) are not succeeding or - even worse - seem wholly ineffective....

Do not depend on the hope of results. When you are doing the sort of work you have taken on, essentially an apostolic work, you may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect.

As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. And there too a great deal has to be gone through, as gradually you struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. The range tends to narrow down, but it gets much more real. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.

You are fed up with words, and I don't blame you. I am nauseated by them sometimes. I am also, to tell the truth, nauseated by ideals and with causes. This sounds like heresy, but I think you will understand what I mean.

It is so easy to get engrossed with ideas and slogans and myths that in the end one is left holding the bag, empty, with no trace of meaning left in it. And then the temptation is to yell louder than ever in order to make the meaning be there again by magic. Going through this kind of reaction helps you to guard against this. Your system is complaining of too much verbalizing, and it is right...

The big results are not in your hands or mine, but they suddenly happen, and we can share in them; but there is no point in building our lives on this personal satisfaction, which may be denied us and which after all is not that important.

The next step in the process is for you to see that your own thinking about what you are doing is crucially important. You are probably striving to build yourself an identity in your work, out of your work and your witness. You are using it, so to speak, to protect yourself against nothingness, annihilation. That is not the right use of your work.

All the good that you do will come not from you but from the fact that you have allowed yourself, in the obedience of faith, to be used for God's love. Think of this more and gradually you will be free from the need to prove yourself, and you can be more open to the power that will work through you without your knowing it.

The great thing after all is to live, not to pour out your life in the service of a myth: and we turn the best things into myths. If you can get free from the domination of causes and just serve Christ's truth, you will be able to do more and will be less crushed by the inevitable disappointments. Because I see nothing whatever in sight but much disappointment, frustration, and confusion...

Our real hope...is not in something we think we can do, but in God who is making something good out of it in some way we cannot see. If we can do His will, we will be helping in this process. But we will not necessarily know all about it beforehand...

From a letter, February 21, 1966

[T]hose who have invented and developed atomic bombs, thermonuclear bombs, missiles; who have planned the strategy of the next war; who have evaluated the various possibilities of using bacterial and chemical agents: these are not the crazy people, they are the sane people. Raids on the Unspeakable

My own peculiar task in my Church and in my world has been that of the solitary explorer who, instead of jumping on all the latest bandwagons at once, is bound to search the existential depths of faith in its silence, its ambiguities, and in those certainties which lie deeper than the bottom of anxiety. In these depths there are no easy answers, no pat solutions to anything. It is a kind of submarine life in which faith sometimes mysteriously takes on the aspect of doubt when, in fact, one has to doubt and reject conventional and superstitious surrogates that have taken the place of faith. On this level, the division between Believer and Unbeliever ceases to be so crystal clear. It is not that some are all right and others are all wrong: all are bound to seek in honest perplexity. Everybody is an Unbeliever more or less! Only when this fact is fully experienced, accepted and lived with, does one become fit to hear the simple message of the Gospel-or any other religious teaching.

The religious problem of the twentieth century is not understandable if we regard it only as a problem of Unbelievers and of atheists. It is also and perhaps chiefly a problem of Believers. The faith that has grown cold is not only the faith that the Unbeliever has lost but the faith that the Believer has kept. This faith has too often become rigid, or complex, sentimental, foolish, or impertinent. It has lost itself in imaginings and unrealities, dispersed itself in pontifical and organization routines, or evaporated in activism and loose talk.

Thomas Merton. "Apologies to an Unbeliever" in Faith and Violence. South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968

[Transcribed from an oral presentation:] There was an old Father at Gethsemani-one of those people you get in every large community, who was regarded as sort of a funny fellow. Really he was a saint. He died a beautiful death and, after he died, everyone realized how much they loved him and admired him, even though he had consistently done all the wrong things throughout his life. He was absolutely obsessed with gardening, but he had an abbot for a long time who insisted he should do anything but gardening, on principle; it was self-will to do what you liked to do. Father Stephen, however, could not keep from gardening. He was forbidden to garden, but you would see him surreptitiously planting things. Finally, when the old abbot died and the new abbot came in, it was tacitly understood that Father Stephen was never going to do anything except gardening, and so they put him on the list of appointments as gardener, and he just gardened from morning to night. He never came to Office, never came to anything, he just dug in his garden. He put his whole life into this and everybody sort of laughed at it. But he would do very good things-for instance, your parents might come down to see you, and you would hear a rustle in the bushes as though a moose were coming down, and Father Stephen would come rushing up with a big bouquet of flowers. On the feast of St. Francis three years ago, he was coming in from his garden about dinner time and he went into another little garden and lay down on the ground under a tree, near a statue of Our Lady, and someone walked by and thought, "Whatever is he doing now?" and Father Stephen looked up at him and waved and lay down and died. The next day was his funeral and the birds were singing and the sun was bright and it was as though the whole of nature was right in there with Father Stephen. He didn't have to be unusual in that way: that was the way it panned out. This was a development that was frustrated, diverted into a funny little channel, but the real meaning of our life is to develop people who really love God and who radiate love, not in a sense that they feel a great deal of love, but that they simply are people full of love who keep the fire of love burning in the world. For that they have to be fully unified and fully themselves-real people. Thomas Merton. "The Life that Unifies" in Thomas Merton in Alaska. New York: New Directions Publishing Corp., 1988:148-149.

The purpose of monastic life is to create an atmosphere in which people should feel free to express their joy in reasonable ways. The final integration and unification of man in love is what we are really looking for. Thomas Merton in Alaska: 147

One of the most disturbing facts that came out in the [Adolf] Eichmann trial was that a psychiatrist examined him and pronounced him perfectly sane. I do not doubt it at all, and that is precisely why I find it disturbing. . . . . The sanity of Eichmann is disturbing. We equate sanity with a sense of justice, with humaneness, with prudence, with the capacity to love and understand other people. We rely on the sane people of the world to preserve it from barbarism, madness, destruction. And now it begins to dawn on us that it is precisely the sane ones who are the most dangerous. It is the sane ones, the well-adapted ones, who can without qualms and without nausea aim the missiles and press the buttons that will initiate the great festival of destruction that they, the sane ones, have prepared. What makes us so sure, after all, that the danger comes from a psychotic getting into a position to fire the first shot in a nuclear war? Psychotics will be suspect. The sane ones will keep them far from the button. No one suspects the sane, and the sane ones will have perfectly good reasons, logical, well-adjusted reasons, for firing the shot. They will be obeying sane orders that have come sanely down the chain of command. And because of their sanity they will have no qualms at all. When the missiles take off, then, it will be no mistake. Thomas Merton. "A Devout Meditation in Memory of Adolf Eichmann" in Raids on the Unspeakable. New York: New Directions Publishing Co., 1964: 45, 46-47. Thought to Remember: [T]hose who have invented and developed atomic bombs, thermonuclear bombs, missiles; who have planned the strategy of the next war; who have evaluated the various possibilities of using bacterial and chemical agents: these are not the crazy people, they are the sane people.

My own peculiar task in my Church and in my world has been that of the solitary explorer who, instead of jumping on all the latest bandwagons at once, is bound to search the existential depths of faith in its silence, its ambiguities, and in those certainties which lie deeper than the bottom of anxiety. In these depths there are no easy answers, no pat solutions to anything. It is a kind of submarine life in which faith sometimes mysteriously takes on the aspect of doubt when, in fact, one has to doubt and reject conventional and superstitious surrogates that have taken the place of faith. On this level, the division between Believer and Unbeliever ceases to be so crystal clear. It is not that some are all right and others are all wrong: all are bound to seek in honest perplexity. Everybody is an Unbeliever more or less! Only when this fact is fully experienced, accepted and lived with, does one become fit to hear the simple message of the Gospel-or any other religious teaching.

The religious problem of the twentieth century is not understandable if we regard it only as a problem of Unbelievers and of atheists. It is also and perhaps chiefly a problem of Believers. The faith that has grown cold is not only the faith that the Unbeliever has lost but the faith that the Believer has kept. This faith has too often become rigid, or complex, sentimental, foolish, or impertinent. It has lost itself in imaginings and unrealities, dispersed itself in pontifical and organization routines, or evaporated in activism and loose talk.

Thomas Merton. "Apologies to an Unbeliever" in Faith and Violence. South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968: 213-214.

[A] faith that is afraid of other people is no faith at all. A faith that supports itself by condemning others is itself condemned by the Gospel.

I came up here [to his hermitage] from the monastery last night, sloshing through the cornfield, said Vespers, and put some oatmeal on the Coleman stove for supper. It boiled over while I was listening to the rain and toasting a piece of bread at the log fire. The night became very dark. The rain surrounded the whole cabin with its enormous virginal myth, a whole world of meaning, of secrecy, of silence, of rumor. Think of it: all that speech pouring down, selling nothing, judging nobody, drenching the thick mulch of dead leaves, soaking the trees, filling the gullies and crannies of the wood with water, washing out the places where men have stripped the hillside! What a thing it is to sit absolutely alone, in the forest, at night, cherished by this wonderful, unintelligible, perfectly innocent speech, the most comforting speech in the world, the talk that rain makes by itself all over the ridges, and the talk of the watercourses everywhere in the hollows! Nobody started it, nobody is going to stop it. It will talk as long as it wants, this rain. As long as it talks I am going to listen. Thomas Merton. "Rain and the Rhinocerous" in Raids on the Unspeakable, 1964

Philoxenos in his ninth memra (on poverty) to dwellers in solitude, says that there is no explanation and no justification for the solitary life, since it is without a law. To be a contemplative is therefore to be an outlaw. As was Christ. As was [Saint] Paul.

The doctrine of man finding his true reality in his remembrance of God in whose image he was created, is basically Biblical and was developed by the Church Fathers in connection with the theology of grace, the sacraments, and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. In fact, the surrender of our own will, the "death" of our selfish ego, in order to live in pure love and liberty of spirit, is effected not by our own will (this would be a contradiction in terms!) but by the Holy Spirit. To "recover the divine likeness," to "surrender to the will of God," to "live by pure love," and thus to find peace, is summed up as "union with God in the Spirit," or "receiving, possessing the Holy Spirit." This, as the 19th-century Russian hermit, St. Seraphim of Sarov declared, is the whole purpose of the Christian (therefore a fortiori [it follows logically] the monastic) life. St. John Chrysostom says: "As polished silver illumined by the rays of the sun radiates light not only from its own nature but also from the radiance of the sun, so a soul purified by the Divine Spirit becomes more brilliant than silver; it both receives the ray of Divine Glory and from itself reflects the ray of this same glory." Our true rest, love, purity, vision and quies is not something in ourselves, it is God the Divine Spirit. Thus we do not "possess" rest, but go out of ourselves into him who is our true rest.

Thomas Merton. "The Spiritual Father in the Desert Tradition" in Contemplation in A World Action. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1971: 287.

In the surrender of himself and of his own will, his "death" to his worldly identity, the monk is renewed in the image and likeness of God, and become like a mirror filled with the divine light. When people are truly in love, they experience far more than just a mutual need of each other's company and consolation. In their relations with each other they become different people: they are more than their everyday selves, more alive, more understanding, more enduring... They are made over into new beings. They are transformed by the power of their love. Love is the revelation of our deepest personal meaning, value and identity. But this revelation remains impossible as long as we are the prisoners of our own egoism. I cannot find myself in myself, but only in another. My true meaning and worth are shown to me not in my estimate of myself, but in the eyes of the one who loves me; and that one must love me as I am, with my faults and limitations, revealing to me the truth that these faults and limitations cannot destroy my worth in the eyes of that one who loves me; and that I am therefore valuable as a person, in spite of my shortcomings, in spite of the imperfections of my exterior "package." The package is totally unimportant. What matters is this infinitely precious message which I can discover only in my love for another person. And this message, this secret, is not fully revealed to me unless at the same time I am able to see and understand the mysterious and unique worth of the one I love.

Thomas Merton. "Love and Need" in Love and Living. Naomi Burton Stone and Brother Patrick Hart, editors. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979: 31.

Love is not only a special way of being alive, it is the perfection of life. He who loves is more alive and more real that he was when he did not love.

More about Merton:

No comments:

Post a Comment