Dear Kev,

I hope you and Cathy are settled in for a long winter's nap.

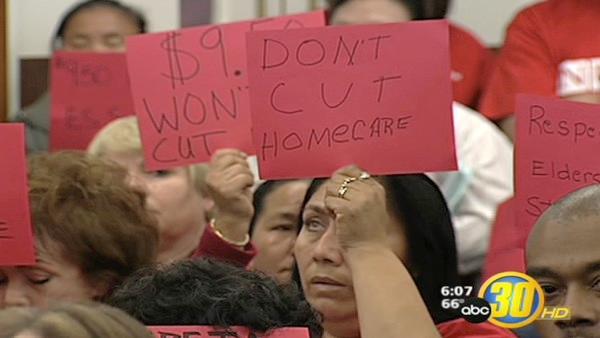

As promised during your recent visit, I am appending my proposal for cost-effective, "homecare" and "assisted-living."

These services would be provided by "au pair" nurses-and-physicians who have recently graduated Latin American universities.

My business interests in the Mexican states of Oaxaca and Yucatan have introduced me to many young professionals who would eagerly embrace the role of "caregiver au pair" - for $1000.00 a month, plus room and board - www.MedicalSpanish.homestead.

For $2000.00 a month, two nurses and/or physicians could live in the same home, providing care for their "patient" and companionship/support for one another.

A template for my proposal already exists; i.e., the longstanding au pair childcare system, made possible by live-in caregivers from abroad - http://en.wikipedia.

With a smidgen of political will, we could conduct an analogous experiment with "homecare au pairs."

I have communicated with congressional Representative, David Price, who appears to like the idea of "homecare au pairs," but -- given widespread hostility to latino immigrants (and other political liabilities) -- he seems reluctant to champion the cause.

I am confident that caregiver "au pairs" can provide high-quality "homecare" for 80% less than the cost of current convalescent care or assisted living. In the process, latino caregivers will provide better, more convivial in-home care than the costly "out-of-home facilities" already in place.

In addition to saving massive amounts of money, older Americans would live out their lives in the comfort of their own homes.

Tragically, legions of "successful" business people have finagled tidy fortunes by "locking America" into astronomically-expensive "for profit" "sickcare" facilities.

These magnates fight tooth-and-nail to prevent implementation of any healthcare method providing high-quality, radically cost-effective care.

Do not believe blather about "the nation's urgent need" for "cost containment."

The people who run the System know that any radical reduction in "the size of the pie" collapses their profits. Given our polito-economic milieu, this circumstance alone makes radical cost-containment proposals "non-starters."

I suspect many profiteers are so blinded by their All-American make-a-buck suppositions that they do not fully realize the economic (and personal) damage they do.

As Upton Sinclair noted: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."

Whenever "The 1%" confronts radical cost containment, Golden Calf worshipers react to "the existential threat" by battling it with the ferocity of momma grizzlies (without the lipstick).

Across the political spectrum -- but particularly on "the right side of the aisle" -- magnates have learned to "milk the system."

In consequence, they have no intention -- none whatsoever -- of putting their dependable cash cows "out to pasture."

Never mind that a given proposal would work better and cost far less.

Indeed, it is, specifically, the prospect of massive cost reduction that triggers thermonuclear resistance within this particular domain of vulture capitalism.

Pax vobiscum

Alan

PS Recently, I asked friend RC -- a Ph.D. in Public Health specializing in geriatric care -- how she herself would set about choosing a long-term care facility.

"Well," she blushed, "my answer is not very scientific. But truth be told, I would learn which care facility (within a 20 mile radius of my home) employs the most filipinos, and that's the facility I would choose."

Very often, "third-worlders" exhibit "soulfulness" and "consideration-for-elders" which youth-oriented Americans have sacrificed on a range of altars.

To name a few...

Self-centered individualism.

Relentless "productivity."

24/7 frenzy.

Deeper involvement with screens than people.

The desire for non-stop entertainment.

The profit motive in healthcare.

***

PPS I will continue with a cover letter to sister Janet written about a year ago when this proposal was first made.

***

Dear Janet,

You probably remember Kelly Lawson from church.

Late in life, her husband, John Lawson, employed a lovely Mexican couple to live with him. The arrangement was joyful all around.

John had been on the verge of signing a contract with a "long term care" facility on Orange Grove Road when I suggested he explore a live-in care arrangement.

For the last two years, I've been trying to interest geriatric care givers -- and state politicians -- in creating an "au pair" program for recently-graduated Latin American nurses (and physicians) so that they can live with - and care for - Americans with no current alternative but "away from home" convalescent facilities.

Last year, I was intrigued to learn from an NPR report (below) that Americans have a legal right to home healthcare (for conditions amenable to in-home treatment) but that this legal right seldom "rises to radar" because the American sickcare system prefers to medicalize as many conditions as possible and therefore emphasizes centralized and more highly-lucrative "away from home" care. http://www.npr.org/2010/12/

The following article explores "in home care" from the vantage of an American nursing organization that calls it "The Last Great Civil Rights Battle"- http://www.ncbi.nlm.

Excerpt: "Historically, nurses have been reluctant to take time away from caring for patients to take part in politics. As is evident from the summaries above and the stories of nurses from all 50 states that follow, nurses have had a change of heart. They have reached the conclusion that they must advocate for the aged, infirm, disabled and dying patients because patients cannot speak out for themselves. More and more nurses are becoming involved. One out of every 44 voters today is a nurse. Nurses show up at the polls; home care nurses have made it their responsibility to help make sure that homebound person vote by absentee ballot. They are also committed to march, to speak out for home care and hospice in what more and more are coming to call The Last Great Civil Rights Battle. They are also pushing for the inclusion of home and community based long-term care as part of national health care reform. They believe that home care is the answer to keeping the 12 percent of Americans who suffer from multiple chronic diseases and generate 75 percent of U.S. health care costs out of the hospital. The historian Arnold Toynbee put all these issues in perspective when he wrote that it is possible to measure the longevity and the accomplishment of any society by a common yardstick. I heard President John F. Kennedy quote Toynbee in a 1963 speech which argued for the enactment of Medicare. Toynbee concluded from his research that you could predict the greatness and the durability of any society by the manner in which it cared for its vulnerable populations: the aged, the children and those suffering with illness and disability. What was at stake, therefore, said President Kennedy, was nothing less than our survival as a nation and our place in history. President Kennedy argued, as do the home care nurses, for us to do what is right for vulnerable Americans in order to preserve for present and future generations the blessings of liberty."

Here's an email I recently sent to State Assemblyman, Josh Stein. (Josh's reply is at the bottom of this page.)

Dear Josh,

I am writing to propose an initiative that would benefit a growing number of Americans, while offering life-changing opportunity to Latin Americans - an initiative that will simultaneously improve international relationships throughout the hemisphere.

Several years ago, my friend John Lawson - after 20 years battling prostate cancer - was nearing the end of his life.

John was within 12 hours of selling his Rougemont home, giving up his beloved dog, Trotamundos, and signing a contract to live the rest of his life at an assisted-living facility in Hillsborough.

The night before he planned to sign that contract, I mentioned to John that our mutual friends Juana and Juan Manuel Balderas might welcome opportunity to live in his home, creating a warm, convivial environment for all of them, while providing the services John needed to live at home until it was time for hospice care.

John loved the idea!

Juana and Juan Manuel loved the idea!

And so, John was able to live the rest of his life -- nearly two years -- at home.

What's more, those two years were probably John's best years at home since wife Kelley died a decade earlier.

John had always been an exuberant lover of life. But during their time together as "a family of three" John was positively ebullient.

Not to burden you with too much detail concerning a "program" that needs much brainstorming and fine-tuning, I would suggest that American society generally -- and aging baby-boomers specifically -- need an in-home living-assistance program analogous to au pair childcare, a model that also provides a measure of "legal precedent."

My two Mexican businesses -- www.MedicalSpanish.

As a result, I am keenly aware of the abundance of recent nursing- and medical school graduates who would embrace the opportunity to provide living-assistance for Americans who need help to continue living in their own homes. (As an aside, I will mention that if it is desirable to avoid the possibility of "a brain drain" I am confident that Mexican universities would eagerly establish training programs to prepare "home aides" whose primary focus would be "living assistance," with a modicum of attention to medical matters as well.)

I have bandied this idea with friends, including Cherie Rosemond PhD, a specialist in geriatrics, and they are all enthusiastic at the prospect. http://www.med.unc.e

I write you today as a result of the impact of yesterday's NPR broadcast - "Care At Home: A New Civil Right" (which I am referencing below).

Just now, as I copied the words "Care At Home: A New Civil Right" I realize that your Mom and Dad could play linchpin roles in making this happen.

I look forward to your thoughts.

Pax

Alan

December 2, 2010

If you ever visit Martin Luther King Jr.'s gravesite in Atlanta, turn around and look across the street at the nursing home in a red brick building. If you look through a big plate-glass window to the left of the front door, you may just see Rosa Hendrix in her wheelchair looking out at you.

Every day, she sits at the window and watches the visitors paying their respects at the civil rights leader's grave. But Hendrix, 87, is fighting her own civil rights battle: to continue her life in her own home.

There's been a quiet revolution in the way the elderly and young people with disabilities get long-term health care. A new legal right has emerged for people in the Medicaid program to get that care at home, not in a nursing home.

States, slowly, have started spending more on this "home- and community-based care." But there are barriers to change: Federal policies are contradictory, and states face record budget deficits. As a result, for many in nursing homes — or trying to avoid entering one — this means the promise to live at home remains an empty promise.

Hendrix has lived at this nursing home for five years. She says no one's ever taken her across the street to visit the grave. She'd like to go, but she'd rather just get out of the nursing home.

"I get up in the morning. Eat my breakfast. Take a shower. And make my bed and all that and sit in this chair all day," she says. "I look out the window. Laugh. At least it gives you something else to look at."

Many people believe that nursing home residents are too sick to live at home. Yet there are many people who have the same disabilities found in nursing homes, who are able to live in their own homes with assistance from family or aides.

There's a growing body of law and federal policy that states when the government pays for someone's care in a nursing home, that person should have the choice to get his care at home. That it's a civil rights issue.

NPR's Investigative Unit looked at this emerging civil right to live at home and found that although it's been established in law and federal policy, the chance to live at home remains an empty promise for many people like Hendrix. States are slow to create new programs. Washington's enforcement record is spotty. And there are often contradictory federal and state policies about how to pay for long-term care.

"People with disabilities are segregated just as African-Americans were segregated," says Sue Jamieson, of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, who is also Hendrix's attorney.

"And this is a perfect example of segregation where we're sitting here today, because Ms. Hendrix is in a wheelchair and had a little trouble with her legs and therefore had some disabilities. She's being segregated, which is a violation of her civil rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act."

The Americans with Disabilities Act — ADA — is a 20-year-old law that bans discrimination on the basis of disability. Eleven years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Olmstead v. L.C. that people who live in institutions like state hospitals and nursing homes but could live successfully on their own have a civil right, under the ADA, to get their care at home.

Since then, federal policy was updated in the recent health care overhaul, which says that states need to spend more money on Medicaid programs for people to receive their long-term care at home.

But federal law requires states to pay for nursing homes, while community-based care programs are optional. So as states face record budget gaps, they only slowly add, or even cut, programs designed to help elderly and disabled people live at home.

Understanding Rosa's Case

Five years ago, Rosa Hendrix fell and hurt her leg. She was sent to a nursing home for therapy and was told it would only be a short-time stay.

"[They s]aid, 'You could do therapy,' and I know therapy's not a, I don't think it's a lifetime situation," Hendrix says. "But anyway, they said ... 'when you get better then you can go home.' "

But the Social Security check she relied upon to pay the rent on that apartment was diverted to pay for her nursing home care. She lost her apartment — and suddenly had no home to go back to.

"That's the typical story," says Alan Weil, who runs the National Academy for State Health Policy, a think tank for state officials. "Once you're in a nursing home, it's hard to get out."

All the supports you need — someone to help you get out of bed, someone to cook for you — already exist in a nursing home, he says. "You become reliant upon the services that are available that you didn't have at home: cooking, getting out of bed in the morning, getting dressed, getting what you need. Without those supports, you can't live at home. And lining up the kind of help you need to get those supports is very hard."

Hendrix is hoping Jamieson, who was also the attorney who brought the landmark Olmstead Supreme Court case, can help her move out of the nursing home.

Recently, Jamieson sat on the small bed in the room Hendrix shares with another woman. The beds are separated by a faded curtain, and the fluorescent light reflects off a dull linoleum floor. All of Hendrix's possessions are in this room: several items of clothing — the ones that haven't been stolen — and a small TV with faded color that Hendrix turns on with a remote control held together by rubber bands.

"It's so frustrating because you don't have very many disabilities," Jamieson told Hendrix. "People with a lot more serious disabilities are living in the community."

"I know that," Hendrix replied.

"And people who can't take a shower and can't dress themselves and can't do all the things you can do," Jamieson said, "are living in the community. So it makes me sad that you're stuck in here."

"Yeah, I'm sad to be," says Hendrix. "Yes, I'm stuck."

Here's what Hendrix and Jamieson are asking the state of Georgia: Help Hendrix find a subsidized apartment. Her Social Security check could help pay for it. Then take the money the state is paying for her care in the nursing home and use some of it to instead pay for an aide to come in, maybe several hours a day, to help Hendrix keep her house clean and do the grocery shopping.

State officials say they don't disagree in principle. But there's a shortage of wheelchair-accessible apartments. And there are thousands of people ahead of Hendrix on a waiting list. There are hundreds of thousands of people across the country waiting for that kind of in-home care.

In October, Georgia avoided going to trial with the U.S. Department of Justice over what the federal government said was the state’s failure to live up to the terms of the Supreme Court's 1999 Olmstead decision. So state officials agreed to spend $77 million over the next two years to set up new programs to help people with mental illness and intellectual disabilities get care in their own homes. It's expected that several hundred, or even a few thousand, will leave state hospitals as a result.

The decision does not apply directly to people, like Hendrix, who live in nursing homes. But Bill Janes, the official in the Georgia governor's office responsible for implementing the agreement, says the creation of an infrastructure of new housing, case managers and in-home health aides for people in state hospitals with mental illness and intellectual disabilities could eventually make it easier for people in nursing homes to find community-based care, too. "It's absolutely a huge step forward," he said.

State-To-State Nursing Home Data Differences

An NPR analysis of unpublished data on every nursing home in America shows that nursing home residents — and how disabled they are — vary from state to state.

For example, according to this exclusive data obtained by NPR's Investigative Unit via a Freedom of Information Act request:

States are supposed to create programs to help with that hard work of moving home, and to get people with mild and moderate disabilities out of nursing homes.

But it's not easy. Many state Medicaid directors get nervous about the idea that living at home is now a civil right. "Where does the state responsibility start and where does the individual responsibility start?" asks Carol Steckel, who until last month was a Medicaid director in Alabama and as the head of the National Association of State Medicaid Directors.

At a meeting of state Medicaid directors, in a hotel outside Washington, D.C., last month, Steckel noted many reasons states are reluctant to expand home-based care. How do you make sure people get good care at home? It's easy, she says, to send an inspector into a nursing home. It's harder to check on hundreds of individuals in their own homes.

And then there's the money question. It's a big problem for states facing all-time-high budget deficits.

"We've got people asking us to do 24/7 at-home care," she says, "which means that we'll be paying $500,000 for one individual. And then you have to debate as a society is that what we want to do versus taking that $500,000 and spending it on prenatal care for 10,000 women. I mean it's a societal question, it's a conundrum almost."

Only in the rarest of cases would it ever cost $500,000. Multiple studies have shown that over the long run, home-based care is cheaper: One study by the AARP Public Policy Institute found that nearly three people can get care at home for the same cost of one in a nursing home. When the Supreme Court established a civil right to home-based care, it specified that it wasn't an unlimited responsibility for states. It had to be something they could do within existing budgets.

Over the past decade, states have steadily increased spending on home-based care — but not nearly enough to meet the need. The number of people on waiting lists has more than doubled, and there are now 400,000 people across the country waiting to get into home-based care.

People like Hendrix, who is trying to get out of that nursing home in Atlanta. "I'd be all right if they'd get me out of here," she says with a rueful laugh. "Cause I just don't need to be; in fact, I don't need to be in any place like this. I need to be out on my own."

Home Or Nursing Home

Every day, she sits at the window and watches the visitors paying their respects at the civil rights leader's grave. But Hendrix, 87, is fighting her own civil rights battle: to continue her life in her own home.

Home Or Nursing Home: America's Empty Promise To Give Elderly, Disabled A Choice

About this series:There's been a quiet revolution in the way the elderly and young people with disabilities get long-term health care. A new legal right has emerged for people in the Medicaid program to get that care at home, not in a nursing home.

States, slowly, have started spending more on this "home- and community-based care." But there are barriers to change: Federal policies are contradictory, and states face record budget deficits. As a result, for many in nursing homes — or trying to avoid entering one — this means the promise to live at home remains an empty promise.

SEARCH: Independence Rates At Nursing Homes

Interactive database: The independence level of residents at nursing homes around the country.TIMELINE: Milestones In Long-Term-Care Policies

Changes in policies and funding have made home- and community-based care a more viable option."I get up in the morning. Eat my breakfast. Take a shower. And make my bed and all that and sit in this chair all day," she says. "I look out the window. Laugh. At least it gives you something else to look at."

Many people believe that nursing home residents are too sick to live at home. Yet there are many people who have the same disabilities found in nursing homes, who are able to live in their own homes with assistance from family or aides.

There's a growing body of law and federal policy that states when the government pays for someone's care in a nursing home, that person should have the choice to get his care at home. That it's a civil rights issue.

NPR's Investigative Unit looked at this emerging civil right to live at home and found that although it's been established in law and federal policy, the chance to live at home remains an empty promise for many people like Hendrix. States are slow to create new programs. Washington's enforcement record is spotty. And there are often contradictory federal and state policies about how to pay for long-term care.

"People with disabilities are segregated just as African-Americans were segregated," says Sue Jamieson, of the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, who is also Hendrix's attorney.

"And this is a perfect example of segregation where we're sitting here today, because Ms. Hendrix is in a wheelchair and had a little trouble with her legs and therefore had some disabilities. She's being segregated, which is a violation of her civil rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act."

The Americans with Disabilities Act — ADA — is a 20-year-old law that bans discrimination on the basis of disability. Eleven years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Olmstead v. L.C. that people who live in institutions like state hospitals and nursing homes but could live successfully on their own have a civil right, under the ADA, to get their care at home.

Since then, federal policy was updated in the recent health care overhaul, which says that states need to spend more money on Medicaid programs for people to receive their long-term care at home.

But federal law requires states to pay for nursing homes, while community-based care programs are optional. So as states face record budget gaps, they only slowly add, or even cut, programs designed to help elderly and disabled people live at home.

Understanding Rosa's Case

"I'd be all right if they'd get me out of here. Cause I just don't need to be; in fact, I don't need to be in any place like this. I need to be out on my own.

- Rosa Hendrix

- Rosa Hendrix

"[They s]aid, 'You could do therapy,' and I know therapy's not a, I don't think it's a lifetime situation," Hendrix says. "But anyway, they said ... 'when you get better then you can go home.' "

But the Social Security check she relied upon to pay the rent on that apartment was diverted to pay for her nursing home care. She lost her apartment — and suddenly had no home to go back to.

"That's the typical story," says Alan Weil, who runs the National Academy for State Health Policy, a think tank for state officials. "Once you're in a nursing home, it's hard to get out."

All the supports you need — someone to help you get out of bed, someone to cook for you — already exist in a nursing home, he says. "You become reliant upon the services that are available that you didn't have at home: cooking, getting out of bed in the morning, getting dressed, getting what you need. Without those supports, you can't live at home. And lining up the kind of help you need to get those supports is very hard."

Hendrix is hoping Jamieson, who was also the attorney who brought the landmark Olmstead Supreme Court case, can help her move out of the nursing home.

Atlanta attorney Sue Jamieson filed the original Olmstead suit that went to the Supreme Court. The ruling states that it's a violation of civil rights law to separate people with disabilities into institutions when they could live in the community with some limited help.

"It's so frustrating because you don't have very many disabilities," Jamieson told Hendrix. "People with a lot more serious disabilities are living in the community."

"I know that," Hendrix replied.

"And people who can't take a shower and can't dress themselves and can't do all the things you can do," Jamieson said, "are living in the community. So it makes me sad that you're stuck in here."

"Yeah, I'm sad to be," says Hendrix. "Yes, I'm stuck."

Here's what Hendrix and Jamieson are asking the state of Georgia: Help Hendrix find a subsidized apartment. Her Social Security check could help pay for it. Then take the money the state is paying for her care in the nursing home and use some of it to instead pay for an aide to come in, maybe several hours a day, to help Hendrix keep her house clean and do the grocery shopping.

State officials say they don't disagree in principle. But there's a shortage of wheelchair-accessible apartments. And there are thousands of people ahead of Hendrix on a waiting list. There are hundreds of thousands of people across the country waiting for that kind of in-home care.

In October, Georgia avoided going to trial with the U.S. Department of Justice over what the federal government said was the state’s failure to live up to the terms of the Supreme Court's 1999 Olmstead decision. So state officials agreed to spend $77 million over the next two years to set up new programs to help people with mental illness and intellectual disabilities get care in their own homes. It's expected that several hundred, or even a few thousand, will leave state hospitals as a result.

The decision does not apply directly to people, like Hendrix, who live in nursing homes. But Bill Janes, the official in the Georgia governor's office responsible for implementing the agreement, says the creation of an infrastructure of new housing, case managers and in-home health aides for people in state hospitals with mental illness and intellectual disabilities could eventually make it easier for people in nursing homes to find community-based care, too. "It's absolutely a huge step forward," he said.

State-To-State Nursing Home Data Differences

An NPR analysis of unpublished data on every nursing home in America shows that nursing home residents — and how disabled they are — vary from state to state.

For example, according to this exclusive data obtained by NPR's Investigative Unit via a Freedom of Information Act request:

State By State

States Find It Difficult To Price Home Health Care

Study concludes that home-based care may save states money over time.MAP: Independence Among U.S. Nursing Home Residents

The degree to which nursing home residents can do things for themselves varies from state to state.

States vary in the portion of Medicaid spending they devote to serving the elderly and disabled.

- In Illinois, almost 21 percent of people in nursing homes can walk by themselves, but fewer than 5 percent can in Hawaii and South Carolina.

- Also in Illinois, almost 12 percent of nursing home residents can bathe themselves without assistance, but in Iowa and South Dakota, just 1 percent can.

- In North Dakota, 60 percent can feed themselves without assistance, but in Utah fewer than 30 percent can.

- In Illinois, nearly 27 percent and in Oklahoma more than 25 percent of residents can use the toilet without assistance. But in South Carolina and Hawaii, fewer than 3 percent can.

- In Georgia, where Rosa Hendrix is fighting her case, fewer than 3 percent can bathe by themselves without assistance; just under 9 percent can dress by themselves without assistance; 17 percent can get in and out of bed by themselves; just under 14 percent can use the toilet by themselves; nearly 9 percent can walk by themselves; and 40 percent can eat without assistance.

States are supposed to create programs to help with that hard work of moving home, and to get people with mild and moderate disabilities out of nursing homes.

But it's not easy. Many state Medicaid directors get nervous about the idea that living at home is now a civil right. "Where does the state responsibility start and where does the individual responsibility start?" asks Carol Steckel, who until last month was a Medicaid director in Alabama and as the head of the National Association of State Medicaid Directors.

At a meeting of state Medicaid directors, in a hotel outside Washington, D.C., last month, Steckel noted many reasons states are reluctant to expand home-based care. How do you make sure people get good care at home? It's easy, she says, to send an inspector into a nursing home. It's harder to check on hundreds of individuals in their own homes.

And then there's the money question. It's a big problem for states facing all-time-high budget deficits.

"We've got people asking us to do 24/7 at-home care," she says, "which means that we'll be paying $500,000 for one individual. And then you have to debate as a society is that what we want to do versus taking that $500,000 and spending it on prenatal care for 10,000 women. I mean it's a societal question, it's a conundrum almost."

Only in the rarest of cases would it ever cost $500,000. Multiple studies have shown that over the long run, home-based care is cheaper: One study by the AARP Public Policy Institute found that nearly three people can get care at home for the same cost of one in a nursing home. When the Supreme Court established a civil right to home-based care, it specified that it wasn't an unlimited responsibility for states. It had to be something they could do within existing budgets.

Over the past decade, states have steadily increased spending on home-based care — but not nearly enough to meet the need. The number of people on waiting lists has more than doubled, and there are now 400,000 people across the country waiting to get into home-based care.

People like Hendrix, who is trying to get out of that nursing home in Atlanta. "I'd be all right if they'd get me out of here," she says with a rueful laugh. "Cause I just don't need to be; in fact, I don't need to be in any place like this. I need to be out on my own."

Home Or Nursing Home

MAP: Community-Based Medicaid Spending By State, 2009

States vary in the portion of Medicaid spending they devote to serving the elderly and disabled.Home Or Nursing Home

Home Care Might Be Cheaper, But States Still Fear It

Study concludes that home-based care may save states money over time.Home Or Nursing Home

Care At Home: A New Civil Right

New federal policies are giving people who need long-term care the right to receive it at home.Comments

Julie Titone (juti) wrote:

A good followup would be looking at assistive technology as a way to keep people in their homes. Washington State University has an expert: http://wsunews.wsu.

Fri Dec 3 13:01:21 2010

A good followup would be looking at assistive technology as a way to keep people in their homes. Washington State University has an expert: http://wsunews.wsu.

Fri Dec 3 13:01:21 2010

Steve O (Steve_O) wrote:

You have a right to buy any services you are able to pay for. And as a matter of policy, a commmunity can decide to use the force of government to deprive certain people of the money needed to pay for things that it wants to spend on other people.

But if someone has a "right" to services that someone ELSE pays for, then that carries with it other implications that even some liberals aren't going to be ready for.

Fri Dec 3 12:57:44 2010

You have a right to buy any services you are able to pay for. And as a matter of policy, a commmunity can decide to use the force of government to deprive certain people of the money needed to pay for things that it wants to spend on other people.

But if someone has a "right" to services that someone ELSE pays for, then that carries with it other implications that even some liberals aren't going to be ready for.

Fri Dec 3 12:57:44 2010

Penny Lane (crooowww) wrote:

Good luck with the nursing home lobby.

Sounds like the lady in the story could use a group home setting where there is a mix of independence and care. Why is she just languishing in a nursing home waiting on subsidized housing where she can have her own apartment?

People without family and friends who will care for them are the ones who pay the highest price for being old and/or sick. Not every old person was decent to those around them and aren't rich enough to provide for an extended time of being dependent.

Fri Dec 3 12:30:49 2010

Good luck with the nursing home lobby.

Sounds like the lady in the story could use a group home setting where there is a mix of independence and care. Why is she just languishing in a nursing home waiting on subsidized housing where she can have her own apartment?

People without family and friends who will care for them are the ones who pay the highest price for being old and/or sick. Not every old person was decent to those around them and aren't rich enough to provide for an extended time of being dependent.

Fri Dec 3 12:30:49 2010

Mary Bryant (mhbryant) wrote:

Of course home care is the best and the least expensive and should be the norm. In Nevada, however, and in other states I'm sure, because in-home personal care assistants (PCA) is an optional Medicaid service, it is set to be completely eliminated as of July 1, 2011! Nursing home care is a mandatory Medicaid service. Something needs to be changed at the federal level or even the people who currently are being cared for at home by PCAs will end up in nursing homes and lose their homes and the supports they have.

Fri Dec 3 11:06:18 2010

Of course home care is the best and the least expensive and should be the norm. In Nevada, however, and in other states I'm sure, because in-home personal care assistants (PCA) is an optional Medicaid service, it is set to be completely eliminated as of July 1, 2011! Nursing home care is a mandatory Medicaid service. Something needs to be changed at the federal level or even the people who currently are being cared for at home by PCAs will end up in nursing homes and lose their homes and the supports they have.

Fri Dec 3 11:06:18 2010

Reality Check (RealityCheckUSA) wrote:

"For the life of me, I don't understand why Georgia and other states are balking"

Being a Georgian, I can tell you. Over the last several years, this state has become peppered with "assisted living" homes. Oh, they are flashy and look like resorts. But they are still nursing homes and very expensive. Who owns them? Why big companies, of course. They are not regulated the way nursing homes once were. In fact, very little nursing care is actually provided. It's a very profitable business. Allow people to choose at-home care and all but the best of these facilities will go out of business. So the Georgia legislature is being lobbied hard. They are politicians and they follow the money.

Understand now?

Fri Dec 3 07:24:28 2010

"For the life of me, I don't understand why Georgia and other states are balking"

Being a Georgian, I can tell you. Over the last several years, this state has become peppered with "assisted living" homes. Oh, they are flashy and look like resorts. But they are still nursing homes and very expensive. Who owns them? Why big companies, of course. They are not regulated the way nursing homes once were. In fact, very little nursing care is actually provided. It's a very profitable business. Allow people to choose at-home care and all but the best of these facilities will go out of business. So the Georgia legislature is being lobbied hard. They are politicians and they follow the money.

Understand now?

Fri Dec 3 07:24:28 2010

Rose Woods (Alsea) wrote:

I am a home care worker in Oregon. For the life of me, I don't understand why Georgia and other states are balking. Home care is such a win-win alternative to nursing home care. I have provided home support for young and old, developmentally disabled folks, and those on hospice end-of-life care. And I have worked in mental hospitals, county jail medical wards, and nursing homes. I have to say, as a lay professional, it is so much better for people to remain in their own homes for as long as it is safe for the both the patient and the caregiver. In nursing homes, often time one aide is supposed to bathe, dress, and feed 15 or more patients in a two-hour span of time. If a coworker called in sick, that number went up, and quality of care declined. When I'm providing services to an in-home patient, my duties are determined by both the case manager AND the patient, to determine how many hours of service the patient needs in a day, and what services are needed. Most seniors don't need around the clock nursing care, just some help so they can keep their homes and persons clean and comfortable, and companionship. That companionship is something that it's not possible to give in a nursing home setting. And more available jobs!

Fri Dec 3 06:32:49 2010

I am a home care worker in Oregon. For the life of me, I don't understand why Georgia and other states are balking. Home care is such a win-win alternative to nursing home care. I have provided home support for young and old, developmentally disabled folks, and those on hospice end-of-life care. And I have worked in mental hospitals, county jail medical wards, and nursing homes. I have to say, as a lay professional, it is so much better for people to remain in their own homes for as long as it is safe for the both the patient and the caregiver. In nursing homes, often time one aide is supposed to bathe, dress, and feed 15 or more patients in a two-hour span of time. If a coworker called in sick, that number went up, and quality of care declined. When I'm providing services to an in-home patient, my duties are determined by both the case manager AND the patient, to determine how many hours of service the patient needs in a day, and what services are needed. Most seniors don't need around the clock nursing care, just some help so they can keep their homes and persons clean and comfortable, and companionship. That companionship is something that it's not possible to give in a nursing home setting. And more available jobs!

Fri Dec 3 06:32:49 2010

Danny DeGuira (Outofbox) wrote:

It's pass time in our dollar conscious world to get BACK to why we are on this planet! How we treat our elderly and respect for death is a measurement of human evolvement!

What a long strange trip it's been-GRATEFUL DEAD!

Fri Dec 3 04:49:51 2010

It's pass time in our dollar conscious world to get BACK to why we are on this planet! How we treat our elderly and respect for death is a measurement of human evolvement!

What a long strange trip it's been-GRATEFUL DEAD!

Fri Dec 3 04:49:51 2010

Dean Shabeldeen (Dshabs) wrote:

My parents are the same age as your subject. They still go to work nearly everyday only to stay active and they can take care of themselves. If your subject is so independent then, why can't she simply leave. If she lives at home alone who then will take her to the grave site of MLK? The truth is she incapable of caring for herself and yearns for earlier days as a young woman with extended family. I honestly feel sympothy for her, but I also know that she sees and interacts with more people where she is than sitting at home alone.

How ironic it is that the story following this one comments on the deficit.

Fri Dec 3 00:49:34 2010

My parents are the same age as your subject. They still go to work nearly everyday only to stay active and they can take care of themselves. If your subject is so independent then, why can't she simply leave. If she lives at home alone who then will take her to the grave site of MLK? The truth is she incapable of caring for herself and yearns for earlier days as a young woman with extended family. I honestly feel sympothy for her, but I also know that she sees and interacts with more people where she is than sitting at home alone.

How ironic it is that the story following this one comments on the deficit.

Fri Dec 3 00:49:34 2010

Helen Highwater (HiH2O) wrote:

This is a serious conundrum.

At home care, 24/7/365, can easily cost $500 per day. This is more than $180,000 per year. For one person.

On the other end of the spectrum is a person who can basically care for themselves, except for a few minor chores. My own mother-in-law fell into that category.

Realistically, there isn't enough wealth in the country to pay for the former, for everyone who needs it.

So, where do we draw the line at what society pays? Who draws the line? How much of our personal wealth is subject to the government's grasp, to be used as someone else sees fit?

Serious questions demand serious answers.

Thu Dec 2 23:16:19 2010

This is a serious conundrum.

At home care, 24/7/365, can easily cost $500 per day. This is more than $180,000 per year. For one person.

On the other end of the spectrum is a person who can basically care for themselves, except for a few minor chores. My own mother-in-law fell into that category.

Realistically, there isn't enough wealth in the country to pay for the former, for everyone who needs it.

So, where do we draw the line at what society pays? Who draws the line? How much of our personal wealth is subject to the government's grasp, to be used as someone else sees fit?

Serious questions demand serious answers.

Thu Dec 2 23:16:19 2010

Wandering Wotan (Wandering_Wotan) wrote:

I'm baffled by the vociferous objections that deny the rights guaranteed under the 5th amendment. What's this about other than one's misreading of the Constitution and what do you all have to lose or gain in this denial?

Like many who've already shared their profound experiences in the article and also via the follow up comments, I too looked after my dad for a year after he was stricken with cancer. It was the hardest thing I've ever done. Cost played little into any decisions we were forced to make and it eventually became a strive to preserve a fleeting livelihood and comfort level upon being released at his insistence from a highly competent and comfortable rehab center after a two weeks stay. Following that, it turned into an issue of dignity. Without the incredible, competent and compassionate visiting nurses and support staff, I'm not sure I could have made it through. And in the end, he passed away as comfortable as could be in his own bed surrounded by things that were most dear to him.

Indeed, insofar as the US has not declined to the state of some penny republic, our elderly should not be deprived of their life and liberty when ailing or when confronted with their end of life stage.

Thu Dec 2 23:07:15 2010

I'm baffled by the vociferous objections that deny the rights guaranteed under the 5th amendment. What's this about other than one's misreading of the Constitution and what do you all have to lose or gain in this denial?

Like many who've already shared their profound experiences in the article and also via the follow up comments, I too looked after my dad for a year after he was stricken with cancer. It was the hardest thing I've ever done. Cost played little into any decisions we were forced to make and it eventually became a strive to preserve a fleeting livelihood and comfort level upon being released at his insistence from a highly competent and comfortable rehab center after a two weeks stay. Following that, it turned into an issue of dignity. Without the incredible, competent and compassionate visiting nurses and support staff, I'm not sure I could have made it through. And in the end, he passed away as comfortable as could be in his own bed surrounded by things that were most dear to him.

Indeed, insofar as the US has not declined to the state of some penny republic, our elderly should not be deprived of their life and liberty when ailing or when confronted with their end of life stage.

Thu Dec 2 23:07:15 2010

***

|

12/7/10

|

Dear Josh,

I very much appreciate your thoughtfulness.

If you learn more, please let me know.

In the meantime, I will contact David Price.

Happy Holy Days to you and to all your loved ones.

Pax

Alan

On Dec 7, 2010, at 11:56 AM, Sen. Josh Stein wrote:

Thanks for your email, Alan. The state's Medicaid Division operates a substantial home health care program. It has not been without controversy over the last couple of years, with allegations of payments being made for unnecessary services. My take is that the state did a poor job creating program incentives in the early 2000s and that greedy providers exploited those incentives. The program has experienced substantial cuts due to the budget crisis. I fully expect it to experience more, even though many are providing excellent services at substantially lower costs than adult care homes provide. I do not see the Republicans being willing to adopt a balanced approach to our continuing budget woes of cuts and revenues; I fear they will cut only.As to who provides the services, Medicaid limits the program to lawful residents, I'm certain. To create a program of in-home living assistance au pairs, I'm fairly confident that the federal government would have to amend the au pair laws to permit it. I'm double checking with legal staff, but I would be surprised if those rules were established by states since they involve visas. Assuming it's federal, I encourage you to share your idea with Rep. Price.I'll let you know if I find out anything different about state authority. I hope you, Denise, and family are great and have a wonderful holiday.

All the best,

Josh

From: Alan Archibald [mailto:alanarchibald@mindspring.com]

Sent: Friday, December 03, 2010 03:13 PM

To: Sen. Josh Stein

Cc:

Subject: Care At Home: A New Civil Right

No comments:

Post a Comment