Republican Representative Joe Wilson Of South Carolina Said Obama Lied But He Didn't.

Pulitzer Prize Winning "Politifact"

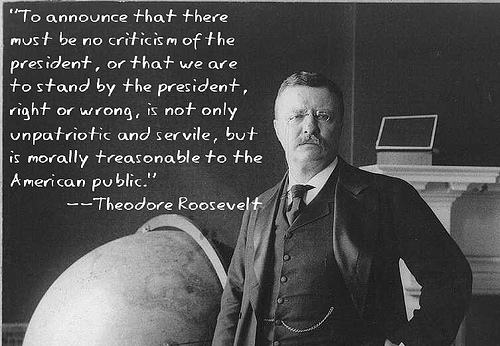

Alan: When political passion overheated during the George W. Bush administration, my conservative friends were quick to conjure the old saw: "It is wrong to criticize a sitting president."

Whether or not this revered chestnut is true --- I believe it is a civic and moral obligation to supply well-reasoned criticism of all sitting presidents --- the GOP has settled in to a swamp of villainous mudslinging, as removed from traditional tethers of truth as they are from the reality of global warming.

"Are Republicans Insane?" Best Pax Posts

"There Are Two Ways Of Lying..." Denis De Rougemont And Donald Trump

Christians Are Their Own Worst Enemy:

Wrecking The Brand

http://paxonbothhouses.

Updated Compendium Of Pax Posts About Donald Trump

The First Heckler

Is Obama the first president to get heckled during an address to Congress?

A Republican representative from South Carolina, Joe Wilson, heckled President Obama

during his speech to Congress Wednesday night. In response to Obama's

statement that the proposed health care bill would not cover illegal

immigrants, Wilson shouted, "You lie!" House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer said, "I have never in my 29 years heard an outburst of that nature

with reference to a president of the United States speaking as a guest

of the House and Senate," while White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel

said, "No president has ever been treated like that. Ever." Is Obama

really the first president to get heckled during an address to Congress?

It depends on what you mean by heckle. Members of

Congress frequently express their disapproval audibly during a

presidential speech. When Bill Clinton outlined his health care plan in

1993, for example, some Republicans snickered, shook their heads, made

faces, and even shouted "no." And when George W. Bush claimed in his

2005 State of the Union that Social Security will be "exhausted and

bankrupt by 2042," Democrats responded with boos.

(At the time, several political talk-show hosts, including Ted Koppel

of ABC, claimed such booing was unprecedented.) But last night may be

the first time a congressman went beyond communal muttering—and

interrupted the president with a loud and denigrating retort.

In the United Kingdom, prime ministers expect less decorum from

representatives. Every Wednesday while the House of Commons is in

session, the prime minister spends half an hour answering questions—and

enduring boos and snide remarks—from Members of Parliament. Harold

Wilson, Labour's prime minister from 1964 to '70, and again from '74 to

'76, is remembered as a particularly able heckler-handler. During a speech on public expenditure, a rowdy MP shouted, "What about Vietnam?" The following back-and-forth ensued:

"The government has no plans to increase public expenditure in Vietnam."

"Rubbish!"

"I'll come to your special interest in a minute, sir."

Even a raucous British MP, however, would think twice before accusing

the prime minister, or another parliamentarian, of lying.

Traditionally, members are expected to avoid insulting or abusive

language, specifically charges of lying or being drunk. Over the years,

speakers (their Nancy Pelosis) have objected to the words blackguard, coward, git, guttersnipe, stoolpigeon, and traitor,

among others. If a speaker deems a word or phrase "unparliamentary," he

will ask the member to formally withdraw it. (For more information on

etiquette in the House of Commons, see this factsheet [PDF].)

Although Americans now expect the president to address Congress in

person, not all commanders-in-chief have done so. George Washington and

John Adams both delivered spoken State of the Union addresses, but

Thomas Jefferson found the practice too monarchic and decided to write

his instead. For the next 112 years, his successors followed suit.

Woodrow Wilson rebooted the practice of spoken addresses to Congress in

1913.

Explainer thanks Richard Ellis of Willamette University and Betty Koed of the Senate Historical Office.

Juliet Lapidos is a staff editor at the New York Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment