Maurice Sendak’s Darkest, Most Controversial Yet Most Hopeful Children’s Book

by Maria Popova

A moving cry for mercy, for light, and for resurrection of the human spirit at a time of hopeless darkness.

One of Maurice Sendak‘s most misunderstood qualities, yet also arguably the very same one that rendered him one of the most innovative and influential storytellers of all time, was his deep faith in children’s resilience and his unflinching refusal to allow the fears and self-censorship of grownups to sugarcoat the world for children, who he believed possess enormous emotional intelligence in processing the dark — an evolution of Tolkien’s assertion that there is no such thing as writing “for children,” which Sendak echoed in his final interview, indignantly telling Stephen Colbert: “I don’t write for children. I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!'”

One of Maurice Sendak‘s most misunderstood qualities, yet also arguably the very same one that rendered him one of the most innovative and influential storytellers of all time, was his deep faith in children’s resilience and his unflinching refusal to allow the fears and self-censorship of grownups to sugarcoat the world for children, who he believed possess enormous emotional intelligence in processing the dark — an evolution of Tolkien’s assertion that there is no such thing as writing “for children,” which Sendak echoed in his final interview, indignantly telling Stephen Colbert: “I don’t write for children. I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!'”

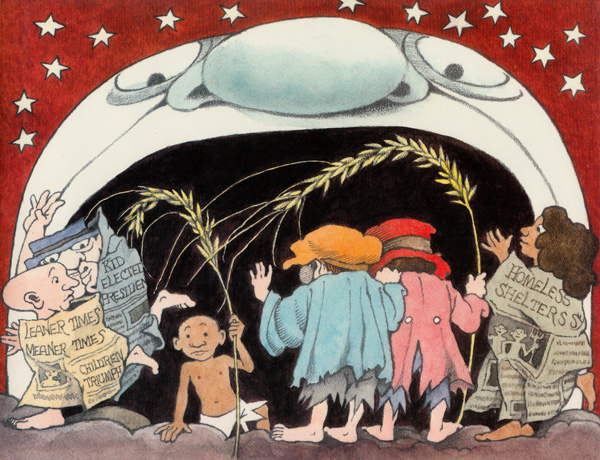

But while many of Sendak’s books have been deemed controversial precisely out of this misunderstanding, from the banning of In the Night Kitchen to the outrage over his sensual illustrations of Melville, no book of his has drawn a thicker cloud of controversy than the 1993 masterwork We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy (public library) — an unusual fusion of two traditional Mother Goose nursery rhymes, “In the Dumps” and “Jack and Gye,” reimagined and interpreted by Sendak’s singular sensibility, with enormously rich cultural and personal subtext.

Created at the piercing pinnacle of the AIDS plague and amid an epidemic of homelessness, it is a highly symbolic, sensitive tale that reads almost like a cry for mercy, for light, for resurrection of the human spirit at a time of incomprehensible heartbreak and grimness. It is, above all, a living monument to hope — one built not on the denial of hopelessness but on its delicate demolition.

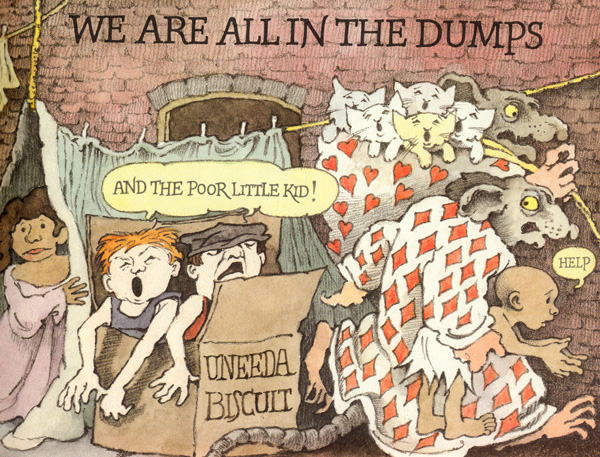

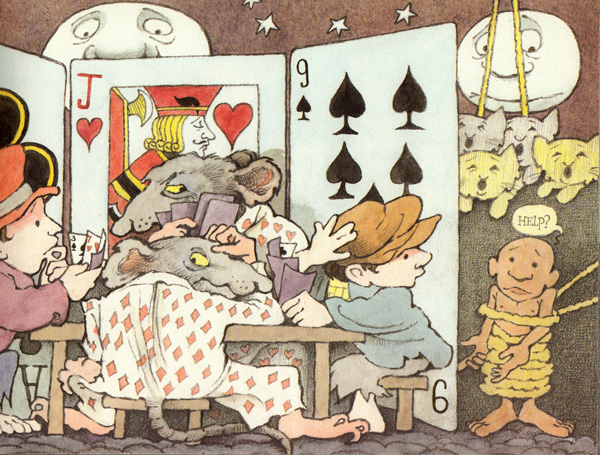

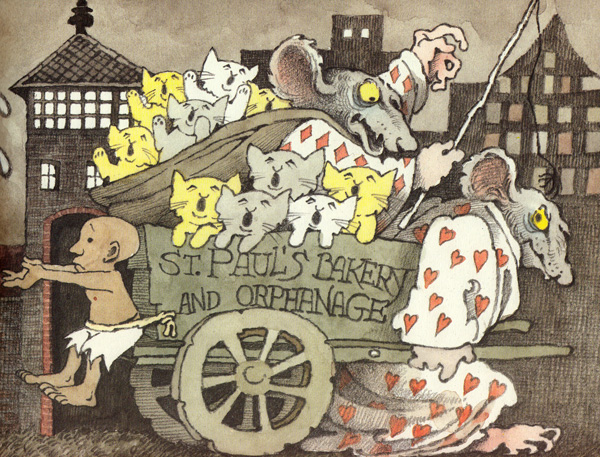

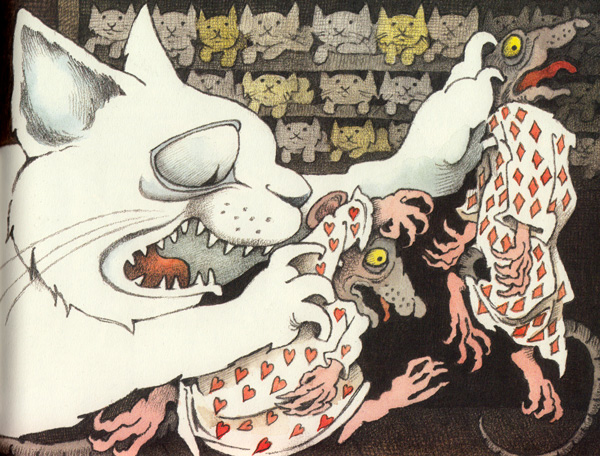

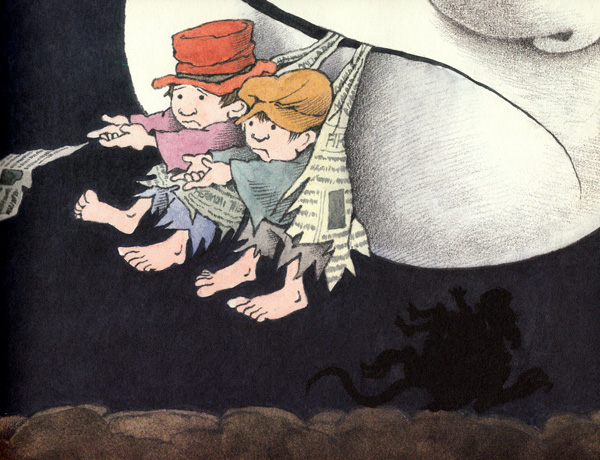

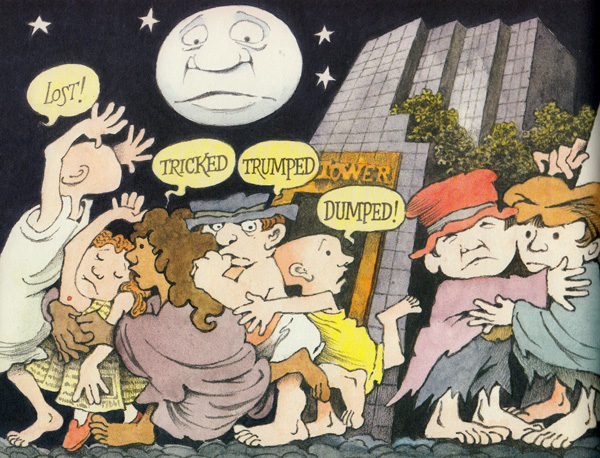

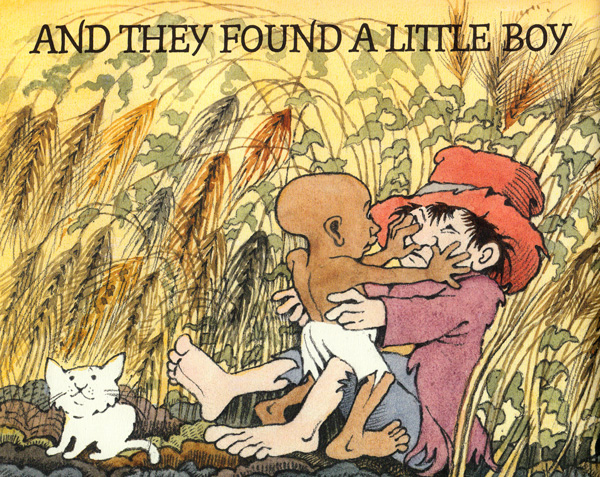

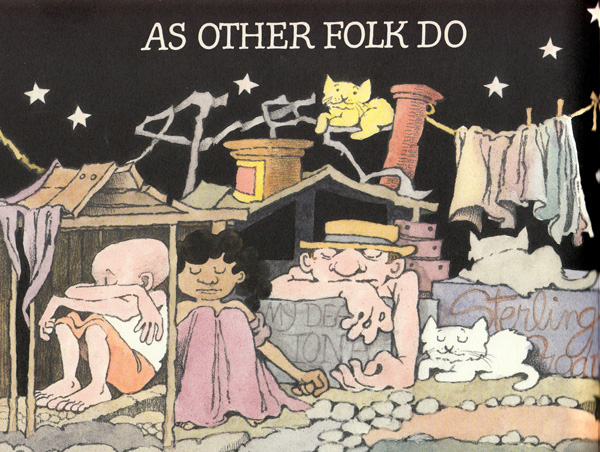

On a most basic level, the story follows a famished black baby, part of a clan of homeless children dressed in newspaper and living in boxes, kidnapped by a gang of giant rats. Jack and Guy, who are strolling nearby and first brush the homeless kids off, witness the kidnapping and set out to rescue the boy. But the rats challenge them to a rigged game of bridge, with the child as the prize. After a series of challenges that play out across a number of scary scenes, Jack and Guy emerge victorious and save the boy with the help of the omniscient Moon and a mighty white cat that chases the rats away.

But the book’s true magic lies in its integration of Sendak’s many identities — the son of Holocaust survivors, a gay man witnessing the devastation of AIDS, a deft juggler of darkness and light.

St. Paul’s Bakery and Orphanage, where the story is set, is a horrible place reminiscent of Auschwitz. In the game of bridge, “diamonds are trumps,” a phrase with a poignant double meaning, subtly implicating the avarice of the world’s diamond-slingers and Donald Trumps in the systemic social malady of homelessness — something reflected in the clever wordplay of the book’s title itself, suggesting that homelessness isn’t limited to the homeless but is a problem we’re all in together, equally responsible for its solution.

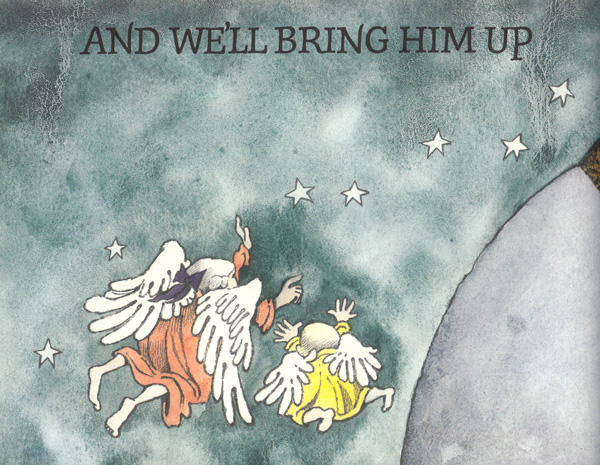

Jack and Guy appear like a gay couple, and their triumph in rescuing the child resembles an adoption, two decades before that was an acceptable subject for a children’s book. “And we’ll bring him up / As other folk do,” the final pages read — and, once again, a double meaning reveals itself as two characters are depicted with wings on their backs, lifting off into the sky, lending the phrase “we’ll bring him up” an aura of salvation. In the end, the three curl up as a makeshift family amidst a world that is still vastly imperfect but full of love.

We are all in the dumps

For diamonds are thumps

The kittens are gone to St. Paul’s!

The baby is bit

The moon’s in a fit

And the houses are built

Without wallsJack and Guy

Went out in the Rye

And they found a little boy

With one black eye

Come says Jack let’s knock

Him on the head

No says Guy

Let’s buy him some bread

You buy one loaf

And I’ll buy two

And we’ll bring him up

As other folk do

In many ways, this is Sendak’s most important and most personal book. In fact, Sendak would resurrect the characters of Jack and Guy two decades later in his breathtaking final book, a posthumously published love letter to the world and to his partner of fifty years, Eugene Glynn. Jack and Guy, according toplaywright Tony Kushner, a dear friend of Sendak’s, represented the two most important people in the beloved illustrator’s life — Jack was his real-life brother Jack, whose death devastated Sendak, and Guy was Eugene, the love of Sendak’s life, who survived him after half a century of what would have been given the legal dignity of a marriage had Sendak lived to see the dawn of marriage equality. (Sendak died thirteen months before the defeat of DOMA.)

All throughout, the book emanates Sendak’s greatest lifelong influence — like the verses and drawings of William Blake, Sendak’s visual poetry in We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy is deeply concerned with the human spirit and, especially, with the plight of children.

Complement this many-layered gem with more of Sendak’s lesser-known work, including his beautiful posters celebrating the joy of reading, his unreleased drawings, his formative, rare vintage illustrations for William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence” and his provocative art for Melville’s Pierre.

No comments:

Post a Comment