"You Didn't Build That"

Falsehood by Decontextualization

***

The Self-Made Man

The story of America’s most pliable, pernicious, irrepressible myth.

n 1990, Susan Orlean published a book called Saturday Night, in which she set out to document how Americans spend their weekly reprieve from work. “Saturday night,” she wrote, “is when you want to do what you want to do and not what you have to do.” One thing people want to do on Saturday night is go out to dinner, so Orlean dedicated a chapter to the restaurant experience. She set this section of the book at the Hilltop Steakhouse, in Saugus, Massachusetts.

The Hilltop occupied a zoning-law-less stretch of Route 1 just north of Boston. A few miles to the south was Weylu’s, a maximalist Chinese restaurant that looked as if it had been airlifted to Essex County from the Forbidden City. A few miles to the north was The Ship, a seafood place in the shape of a schooner that had somehow run aground along the landlocked highway.

Even with these neighbors, the Hilltop stood out. It had a 68-foot neon cactus sign, a herd of life-size fiberglass cattle grazing out front, and an ever-present line of customers waiting for one of the 1,400 seats in its six dining rooms, each named for an Old West outpost, from Dodge City to Santa Fe. Attached to the restaurant, in the rear, was the Butcher Shop. According to Orlean, it was the largest refrigerated store in the world. At the peak of the Hilltop’s popularity, it was not uncommon for patrons to eat a steak in the restaurant, bundle up for a visit to the butcher shop, and emerge into the 7-acre parking lot with a full stomach and an armload of sirloin for home.

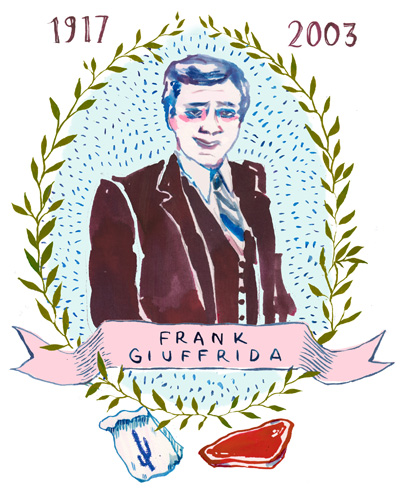

Emblazoned on the Hilltop’s cactus, in a flowery script, was the signature of its founder, Frank Giuffrida. The son of Sicilian immigrants, Giuffrida grew up in Lawrence, Massachusetts, an old mill town on the banks of the Merrimack River. His father died when Giuffrida was still a boy, so Frank dropped out of school and started working in the family business, a butcher shop. In the early 1960s, he sold that store and used the proceeds to buy what he described as a seedy gin mill on Route 1 called the Gyro Club. There he would fulfill the lifelong dream of a John Wayne–loving meat-cutter: opening a Western-themed steakhouse, with his wife Irene serving as hostess.

Giuffrida’s formula was large portions at low prices; he bet that he could make up for his thin margins with high volume. It worked. In 1987, the Boston Globe reported that the Hilltop was spending $20,000 a year just to supply its patrons with doggie bags. People couldn’t finish their $11 steaks—and they couldn’t get enough of the place. By the time Orlean interviewed Frank and Irene, they had built the Hilltop into a local institution doing business on a national scale. “Last year, the Hilltop grossed forty-seven million dollars and served food to two and a half million people,” Orlean wrote. “This represents more food sold and more people served than at any other single restaurant in the country.” New York City’s Tavern on the Green was a distant second.

Orlean embedded with a platoon of seen-it-all waitresses, studied the rituals of the customers waiting for a table (who played whist, completed crosswords, and drank cocktails to kill time during what could be a two-hour wait), and witnessed two large gentlemen order a cheeseburger and a tenderloin (each). There was one character, however, missing from Orlean’s otherwise comprehensive account: the Hilltop’s owner. Giuffrida had sold the restaurant two years earlier, to a local businessman named Jack Swansburg.

The first thing I asked my father when he told me he was buying the Hilltop was whether his signature would replace Giuffrida’s on the giant cactus. His response: “Nobody wants to buy a steak from Jack Swansburg.” Frank’s name would stay on the sign, and Frank and Irene would fly in from Florida, where they’d retired, when reporters turned up to write about the restaurant. This made good business sense—new ownership can spook the diehards—but it frustrated my efforts, as an 11-year-old, to boast that my father owned the busiest restaurant in America. It was like telling people it was my dad, not Red Auerbach, calling the shots in the Celtics’ front office. People didn’t think I was bragging. They thought I was lying.

Frank Giuffrida died of a stroke in 2003, and I never got to ask him why he decided to sell the Hilltop to my father. Surely Giuffrida had other suitors for a business so profitable and iconic, and surely a man who inscribes his name on a 68-foot neon cactus has thought about his legacy. But my guess is that he saw my father as a kindred spirit. Though Jack had no experience running a restaurant, or for that matter any business in the service industry, he was, like Frank, a self-made man, a blue-collar guy from Winthrop, Massachusetts, who had pulled himself up by his proverbial bootstraps.

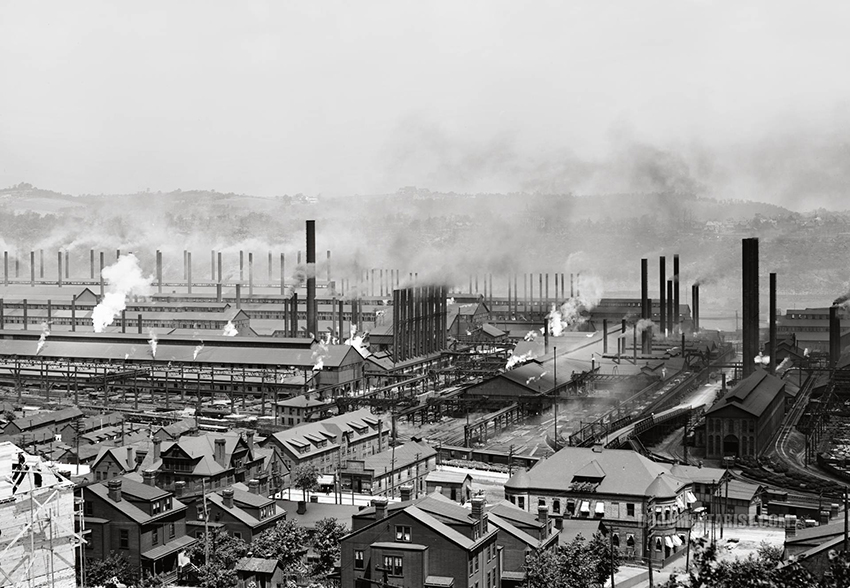

Image via Wikimedia Commons

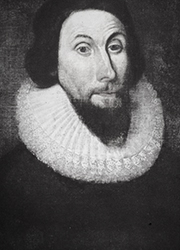

In 1630, John Winthrop composed his famous sermon in which he set forth his vision for a community that would be “as a city upon a hill,” a beacon of Puritan virtue shining from the New World. The city he founded was Boston. The town bearing Winthrop’s name is a working-class enclave nestled between Logan Airport and the plant that treats Greater Boston’s sewage. My father grew up on the top floor of a clapboard double-decker near Belle Isle Inlet, a brackish basin that separates Winthrop from Logan’s runways. When he turned 15, Jack’s father, a truck driver, told him it was time he found a job. A local roofing company was hiring. So my father became, in his typically earthy turn of phrase, a “shit-bum roofer.”

Roofing in that era was a particularly grueling trade. Higher-skilled laborers—carpenters, sheet metal workers—looked down on the men who made their living pouring 400-degree asphalt while exposed to the harsh New England elements. A roofer, however, still took pride in his work; when we’d drive through the Boston area, my father could never resist pointing out the projects he’d worked on. “See that brick building?” he’d say, gesturing toward an anonymous structure alongside the Southeast Expressway. “I put the roof on that.” Once, my sister reported that a favorite elementary school teacher did roofing work over the summer, thinking this would please our father. “He’s not a roofer,” Jack shot back. “He’s ashingler.”

By that time my father had left the roofing business. He had started his own roofing company in his mid-20s, turned it into a profitable concern, and cashed out so he could invest in more lucrative enterprises. My father has never had any vanity about what sort of business he’s in, so long as he sees “a return on my invested dollars,” a phrase he repeats, in his thick Boston accent, like a mantra. Over the course of my childhood he owned a paving company, a company that installed garage door openers, and, my favorite, a company that refurbished golf balls. He would pay a guy to fish shanked balls out of golf course water hazards, power-wash the muck out of the dimples, and sell the balls to driving ranges and country clubs at a nice profit.

Mostly, though, my father made his money in real estate. Specifically, he bought and sold buildings he affectionately refers to as “pigs”: big, ugly industrial spaces. Buildings with saw-tooth roofs and wrinkle-tin sides. Buildings that housed sheet metal shops, produce-industry middle-men, discount-furniture-store distribution hubs. In his late 20s and early 30s, the years before he bought the Hilltop, he built a small empire in the hardscrabble ring around Boston: in Charlestown, Everett, the precincts of Cambridge that Harvard and MIT students studiously avoid, and in Chelsea, where his first roofing shop had been. I once asked my father how he knew when a pig was a good investment, since aesthetics, and even location, seemed not to factor into his calculus. “When I’m looking at a building,” he said, “I drive up to it. If my balls tingle, I buy it. Otherwise, I don’t.”

Balls play an outsize role in my father’s vocabulary. When something impresses him, he says “that’s the balls.” When he admires someone, it’s typically because that person has done something that “took balls.”But his suggestion that his loins can detect promising real estate opportunities is a cagey bit of false modesty. When pressed to explain a given transaction, it usually emerges that he found an angle no one else had thought to exploit, or worked the deal harder than anyone else was willing to work it. Driving through Chelsea recently, he pointed out a trio of unlovable buildings he’d bought early in his career. All three had tenants at the time, but the seller had never bothered to ask them if they might like to buy the buildings they’d been leasing. My father bothered to ask. By the time he signed the purchase and sale agreement for the three properties, two of the tenants had agreed to buy their respective spaces from him, at a combined price that would cover the cost of the three-building acquisition. In essence, he got the third building, a 25,000-square-foot warehouse, for free.

My father has dozens of stories like this, though not all of them have happy endings. The Hilltop, the most prominent business he ever owned, was in the end his biggest failure. He bought the restaurant around the time it dawned on Americans that eating red meat three times a week wasn’t a great way of maintaining heart health, and sold it before the Atkins diet brought people back to the stockyard in droves. (The Hilltop went out of business in 2013, 20 years after my father sold it.) But whether he was laying asphalt on a Chelsea rooftop or pricing out doggie bag suppliers in Saugus, my father never doubted that he could make something of himself if he put the time in—and he never doubted that anyAmerican could make something of himself if he put the time in.

In this, he is typical. When the Pew Economic Mobility Project conducted a survey in 2009—hardly a high point in the history of American capitalism—39 percent of respondents said they believed it was “common” for people born into poverty to become rich, and 71 percent said that personal attributes like hard work and drive, not the circumstances of a person’s birth, are the key determinants of success. Yet Pew’s own research has demonstrated that it is exceedingly rare for Americans to go from rags to riches, and that more modest movement from the bottom of the economic ladder isn’t common either. In fact,economic mobility is greater in Canada, Denmark, and France than it is in the United States.

I’ve always admired what my father accomplished, and how he accomplished it, while not quite sharing his confidence that his experience was repeatable, especially in our current economic moment. The yawning gap between the dearly held ideal of the self-made man and the difficulty of actually improving your station in America, particularly if you’re poor, made me wonder about the utility of the rags-to-riches story. Is it a healthy myth that inspires us to aim high? Or is it more like a mass delusion keeping us from confronting the fact that poor Americans tend to remain poor Americans, regardless of how hard they work?

GIF by Lisa Larson-Walker/Slate

The very language we use to describe the self-made ideal has these fault line embedded within it: To “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” is to succeed by dint of your own efforts. But that’s a modern corruption of the phrase’s original meaning. It used to describe a quixotic attempt to achieve an impossibility, not a feat of self-reliance. You can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps, anymore than you can by your shoelaces. (Try it.) The phrase’s first known usage comes from a sarcastic 1834 account of a crackpot inventor’s attempt to build a perpetual motion machine.

I wanted to know how the self-made ideal got lodged so firmly in the American mind that even a finding that France—France!—is a better place to move on up has done little to diminish our sturdy belief in our exceptionalism. What I found is a mythology at once resilient and pliable, one that has been adapted by its purveyors again and again to suit the needs of the times. Benjamin Franklin is undoubtedly the original self-made man, but there’s only a passing resemblance between him and Andrew Carnegie, an exemplar of the ideal from a century later. (Franklin was a famous champion of industriousness, Carnegie a famous champion of leisure.) Indeed, Franklin might not even recognize the version of himself that became the subject of veneration in the decades following his death in 1790. The wave of Franklin biographies that appeared in the rapidly expanding republic of the early 1800s emphasized the qualities that spoke to aspiring men of business and fudged the ones that didn’t. From the beginning, selling the self-made dream to those who hoped to live it was a lucrative business itself. In a country where everyone thinks he’s bound to be a millionaire, you can make a fortune selling the secret to making that fortune.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

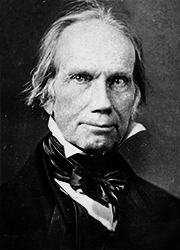

The first half of the 19th century was something of a heyday for the self-made man. Among other things, it’s when Henry Clay is said to have coined the term, while arguing on the Senate floor for a protective tariff he believed would benefit “enterprising self-made men, who have whatever wealth they possess by patient and diligent labor.” Around that time, it became popular to publish omnibus biographies of self-made men. Charles C.B. Seymour’s Self-Made Men (1858) chronicled 60 such figures; Harriet Beecher Stowe limited herself to 19 subjects, among them her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, who extolled the self-made virtues from his pulpit at Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church.

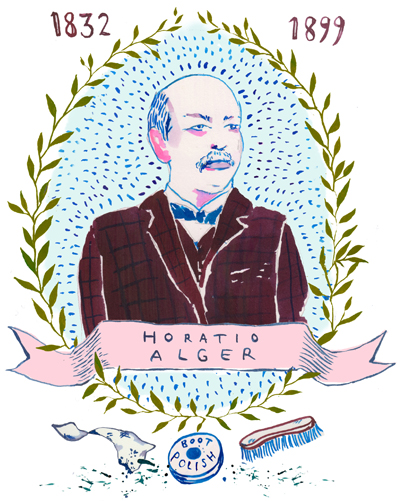

Taking a page from this approach, I’ve traced the evolution of the self-made myth through the lives of six men and one woman, each of whom lived a version of the self-made story while also participating in its reinvention for a new generation. Their stories demonstrate the undeniable allure of the myth and the shocking ways in which it often diverges from reality. Even Horatio Alger, the man whose name became synonymous with the rags-to-riches narrative, turns out not to be who we think he is. The writer’s story is far more sordid than anything you’ll find in his cheery tales of aspiring bootblacks and newsboys, which themselves have been misremembered and misunderstood.

There is a related but distinct line of self-made men in the political realm. Ever since Andrew Jackson, candidates have tended to fare better when there was a log cabin in their background. But my focus is on self-made businessmen—people like my father and Frank Giuffrida, and probably like someone you know, too. As the story of Benjamin Franklin illustrates, for most Americans, the allure of public service has always paled beside the allure of wealth.

hen Benjamin Franklin was 16 years old, he happened upon a book extolling the virtues of vegetarianism. The idea intrigued him; he decided to give it a try. At the time, Franklin was indentured to his older brother James, a Boston printer, who provided for Benjamin’s room and board. James found his brother’s new dietary restrictions irritating. “My refusing to eat Flesh occasioned an Inconveniency,” Franklin later recalled, “and I was frequently chid for my singularity.”1 Not wanting to be a burden, or to be further chid, Benjamin proposed a deal: If James would give him half the amount he’d been paying for board, he would arrange for his own meals.

James agreed, and was happy for the savings. Benjamin, meanwhile, taught himself a few simple vegetarian recipes (boiled potato, hasty pudding) and soon discovered that he could get by on half the sum his brother was paying him. Franklin invested the remaining money in books to feed his hungry mind. What’s more, his “light Repast” requiring only a few minutes to prepare and consume, he found he now had more free time, which he devoted to the study of arithmetic and geometry, subjects that had bedeviled him during his brief formal schooling.

Embedded in this anecdote, which Franklin tucked into the opening pages of his Autobiography, are all the ingredients of its author’s genius: his curiosity, his eagerness to experiment, his diplomacy (in proposing to James a mutually beneficial arrangement), his temperance (in abjuring a richer meal), his frugality (in stretching his coppers to buy books), and his industry (in using his free time for self-improvement). The story itself, and the deceptively matter-of-fact way in which Franklin relates it, testifies to his sly literary gifts, and to his knack for the 18th-century equivalent of the humblebrag.

The story of the self-made man begins with Franklin. Though he was hardly the first man to rise from poverty to prominence, no one in America’s short history had started out so low and ended up so high. Franklin, the tenth son of a Boston candle-maker, became a world-famous scientist, an influential patriot and diplomat, and, not least, a wealthy man of business. But America’s self-made story also begins with Franklin because of his talents as a writer. In the Autobiography, Franklin offered an irresistible account of his unlikely path to prosperity, one that would thrill later generations even as they misinterpreted it. For Franklin, succeeding in business had been a means to an end. The wealth he accumulated freed him to devote himself to loftier endeavors: science, public service, the pursuit of moral perfection.2 Franklin didn’t set out to be the face of American capitalism, but in the decades after his death, that’s what he became.

I asked my father recently if he’d ever read Franklin’s Autobiography. “No,” he replied, tapping his back pocket. “But Benjamin Franklin and I are well acquainted.”

Franklin’s brother James was a cruel master, taken to expressing his displeasure with his young apprentice by beating him. Franklin, understandably, took this “extreamly amiss,” though he would later credit his brother’s “harsh and tyrannical Treatment” with instilling in him his lifelong “Aversion to arbitrary Power.” The time would come when Franklin would express that aversion to some of the most powerful men in Europe. For the moment, he just wanted to escape his brother’s harsh rule. When an opportunity presented itself, he ran away, securing passage on a sloop bound for New York, under the pretense that he’d “got a naughty Girl with Child”—apparently a more acceptable excuse for traveling as an unaccompanied minor than breaking your indenture. Finding no printing work in New York, Franklin pushed on to Philadelphia.

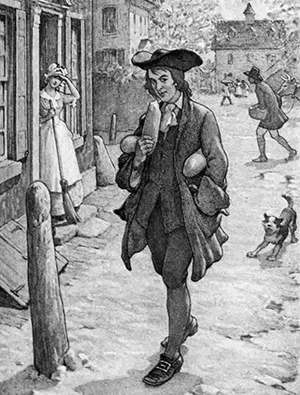

Image via Project Gutenberg

Franklin’s account of the unpromising figure he cut on his first morning in his adopted city is one of the most famous passages in American literature, and an ur-text in the mythology of the self-made man. With little to his name save the shirt on his back and the change of stockings he’s stuffed into the pockets of his pants, Franklin sets out down Market Street looking for something to eat. Locating a baker, he asks for a biscuit “such as we had in Boston,” but is told they don’t make that kind of biscuit in Philadelphia. So Franklin asks instead for three pennies worth of whatever bread is on offer, prompting the baker to hand him “three great Puffy Rolls”—far more sustenance than Franklin has bargained for. With no room in his pockets thanks to the spare hosiery, Franklin walks back up Market Street, a giant roll under each arm, noshing on the third. His future wife, Deborah Read, happens to be standing in her father’s doorway as Franklin walks by and bears witness to his “most awkward ridiculous Appearance.”

Franklin lingers on the image of his ridiculous, roll-toting self so that we might “compare such unlikely Beginnings with the Figure I have since made there.” After Franklin, no man could claim to be self-made if he couldn’t produce an account of his own unlikely beginnings, the less auspicious the better. (In his memoir, the successful 19th-century clock-maker Chauncey Jerome tried to one-up Franklin by wandering around New Haven on his first day in the city while carrying a pile of clothing, bread, and some cheese.3) The familiarity of the trope today dulls the impact of what at the time was a radical stroke. Implicit in Franklin’s invitation to compare this lowly born boy to the prominent man he would become is the idea that any man might aspire to similar heights.4

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Ever practical, Franklin didn’t merely recount his rise in the Autobiography; he also described the “conducing Means” by which he rose, believing his readers “may find some of them suitable to their own Situations, and therefore fit to be imitated.” For years, in the pages of his popular Almanack and in the voice of his literary creation, Poor Richard Saunders, Franklin had extolled the virtues of industry, frugality, and temperance. The wisdom was largely borrowed from the Puritan ethic, which Franklin had gleaned from the writings of Cotton Mather and from his own father, who was fond of quoting a line from Solomon: “Seest thou a Man diligent in his Calling, he shall stand before Kings.” (“I did not think that I ever should literally stand before Kings,” Franklin writes in his memoirs, before permitting himself to report that in fact he had stood before five.)

In Franklin’s hands, dour Puritanical and biblical admonitions became homespun maxims, as well-known today as they were in 1750: “never leave that to tomorrow, which you can do today”; “early to bed and early to rise …”; “well done is better than well said.” In the Autobiography, Franklin avows that he grew his fledgling printing house by observing Poor Richard’s advice—and by making a show of it. When Franklin needed to replenish his stocks of paper, he would run the errand himself, pushing the reams down the street in a wheelbarrow to advertise his dedication to his trade. “Thus being esteem’d an industrious thriving young man,” he wrote, “the Merchants who imported Stationery solicited my Custom, others propos’d supplying me with Books, and I went on swimmingly.”

Franklin’s Autobiography was published shortly after his death in 1790, at a moment when America itself was getting along swimmingly. The book quickly found a readership among Americans eager to take advantage of the exploding economic opportunities in the new republic. It was a time, writes the historian Joyce Appleby in Inheriting the Revolution (2000), when an enterprising tanner could thrive with “a bit of pluck, a skill like shoemaking, and an honest face,” and a farm boy with a good idea (Austin Burt, say, who invented the typewriter) could start a business with “little or no capital.”5 There were no guarantees of success, but the opportunity was real. A great story of self-making had arrived at precisely the moment when Americans were primed to hear it.

A cottage industry thus grew up around disseminating Franklin’s story to the country’s growing ranks of entrepreneurs. Twenty-two editions of the Autobiography were published between 1794 and 1828, many of them packaged with “The Way to Wealth,” his aggregation of Poor Richard’s advice pertaining to business.6 At the Franklin Collection at Yale University, I found shelves full of early-19th-century editions of Franklin’s life intended specifically for boys, with didactic introductions and lively illustrations of their hero’s adventures. And the books really did inspire. In The Self-Made Man in America (1954), Irvin G. Wyllie notes that Thomas Mellon, the founder of the eponymous banking fortune, was encouraged to leave his family farm by the Autobiography, which he read in 1828, at age 14.7 “I had not before imagined,” Mellon said, “any other course of life superior to farming, but the reading of Franklin’s life led me to question this view.” When Mellon had made his own name, Wyllie writes, “he bought a thousand copies of Franklin’s Autobiography, which he distributed to young men who came seeking advice and money.”8 Outside his bank, Mellon erected a statue of Franklin.

Franklin was undoubtedly proud of his rise from obscurity. Throughout his life, he would remind his correspondents of his humble origins by signing his name “B. Franklin, Printer.” (Ever the printer, in theAutobiography, and in the famous epitaph he composed for himself, Franklin described his mistakes not as sins to be repented but errata he’d correct if permitted a second edition.) He was also proud of the role he’d played in founding a nation where such a rise was possible. Yet Franklin’s intent in setting down his life was not to establish himself as the founding father of bourgeois striving. He recognized that whatever happiness, virtue, and greatness he’d achieved was predicated on his early success in business, which allowed him to retire at age 42—the midpoint of his life, it turned out—and to devote his remaining 42 years to public service and moral improvement. He made room for his business affairs in theAutobiography, describing the qualities that had allowed his printing house to thrive, but lavished far more attention on his civic contributions (which ranged from founding one of America’s first libraries to founding one of its first volunteer fire companies) and on his moral philosophy (recounting in detail his effort to better himself through the practice of 13 virtues).9 It was his success in these endeavors, more so than mere money-making, for which he hoped to be remembered.

In The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (2004), historian Gordon Wood ranks Franklin second only to Washington in his importance to the Revolutionary cause.10 Even John Adams, his most bitter contemporary detractor, allowed that Franklin’s contributions to science had made his reputation “more universal than that of Leibnitz or Newton.”11 And yet the founding of a nation, and even the mastery of electricity, paled in comparison to Franklin’s most ingenious invention: the idea that a man could make his own fortune in the world, regardless of his station, if he put in the work.

Image viaYale University Art Gallery

So eager was the first generation of Americans to believe in this idea, in fact, that they manipulated Franklin’s story to accentuate his self-making. One of the 13 virtues Franklin had aspired to was humility (though, by his own admission, he struggled with this one mightily); as Wood notes, Franklin took pains in his memoirs to describe his rise to prominence in unassuming terms. In the statement of purpose on the Autobiography’s first page Franklin explains that future generations might take an interest in his life story on account of his “having emerg’d from the Poverty and Obscurity in which I was bred, to a State of Affluence and some Degree of Reputation in the World.” Franklin’s wording allows room for other forces beside his own will to have contributed to that emergence—the help of strangers, for instance, of which he had much. But Franklin’s grandson, William Temple Franklin, suffered no such bout of humility on his grandfather’s behalf as he prepared his version of the memoirs for publication.12 “From the poverty and obscurity in which I was born,” he rendered the line, “I have raised myself to a state of affluence and some degree of celebrity in the world.” In William’s edition, which would become the standard text for the prosperous first half of the 19th century, his grandfather’s rise was entirely and explicitly his own doing.13 By the time anyone got around to correcting the erratum, B. Franklin the industrious printer and self-made man had became a figure of American adoration.

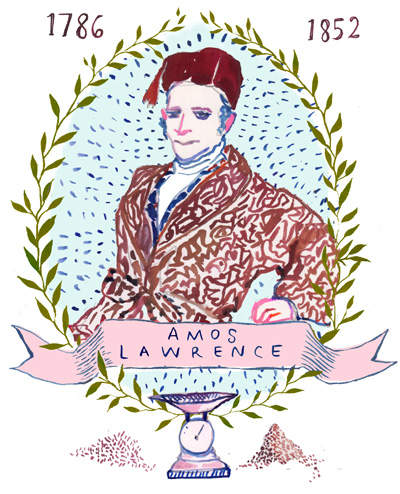

mos Lawrence was one of the many young American men who left behind the family farm to seek opportunity in the city in the years following Franklin’s death. Though Lawrence is not well-remembered today, the dry goods merchant was a fixture of the success literature of the mid-19th century, when authors sought to satisfy the growing demand for stories about self-made men. “When a poor boy becomes a wealthy, influential, virtuous, and honored man,” wrote William Makepeace Thayer, a widely read author in his day, “it is worth while for the young to ask, ‘How?’ ” InThe Poor Boy and Merchant Prince, Or Elements of Success Drawn From the Life and Character of the Late Amos Lawrence (1857), Thayer promised an answer.

To an extent, books like Thayer’s merely rehashed the ethos that Franklin had established. Poor Boy has chapters titled “Industry” and “Frugality,” as well as one called “Not Above Business,” in which Franklin and his wheelbarrow make a cameo.14 Accounts of Lawrence’s rise invariably begin with the same anecdote, in which our young hero demonstrates the virtue of temperance. Lawrence apprenticed with a merchant whose clerks were in the habit of drinking, each forenoon, a mixture of rum, raisins, sugar, and nutmeg. Finding himself looking forward a bit too fondly to the appointed hour for “dramming,” Lawrence resolves to abstain from drink entirely, “thinking the habit might make trouble if allowed to grow stronger.” (“That deed was truly heroic!” cheers Thayer.) As for food, Lawrence took only bread and water, the quantities of which he measured on a scale he kept on his desk. When he died, his son found among his papers a memorandum book titled “Record of Diet and Discipline for 1839 and 1840.”15 Eat your heart out, Dr. Franklin.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

But Lawrence wasn’t merely a living exemplar of Poor Richard’s maxims. His popularity among antebellum success writers was also a function of his religious rectitude. Here, Franklin had posed a challenge for the promoters of the self-made ideal: Though virtuous, Franklin was a youthful skeptic, a Deist, and never one for churchgoing. Authors worried that his lack of religiosity wouldn’t play in the pious country villages where the self-made men of tomorrow were presumably to be found.16 Some, including Parson Weems, the enterprising bookseller who invented the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, simply bent the truth to their purposes. Weems wrote a highly fictionalized life of Franklin, which transformed him into a loyal disciple of Christ.17 (Weems was on to something—his book likely outsold Franklin’s own.18) Others turned to men like Lawrence, a God-fearing Sabbath-observer whose diary and correspondence—upon which Thayer based his narrative—made Cotton Mather look like Ned Buntline.

Between 1844 and 1845, Lawrence lost 10 close friends and family members to death, including a daughter, who’d just delivered twins, and his youngest son, a student at Harvard. Even by the standards of the time it was a devastating toll. Yet Lawrence begins 1846 with a remarkable diary entry, in which he interprets the losses as a test of his faith and a challenge for the new year. “What am I left here for, and the young branches taken home?” he writes. “Is it not to teach me the danger of being unfaithful to my trusts?”19 He resolves to recommit himself to the pursuit of spiritual perfection, in large part by accelerating his already prodigious rate of charitable giving. At the Massachusetts Historical Society, I paged through the pocket-sized account book in which Lawrence recorded his every donation: $1 to a poor woman to buy wood, $10 to print copies of a speech supporting temperance, $100 toward the education of Nathan Hale’s son, $10,000 for the construction of the Bunker Hill Monument.

Lawrence’s piety was important to Thayer not just because of the perceived religious devotion of the book’s intended audience. His godliness also spoke to a fear that accompanied the nation’s breakneck economic growth. For all the opportunity it afforded young men, the economic boom also brought temptation, especially for those ingenuous boys leaving behind the purity of the country for the fleshpots of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.20 Thayer works himself into a lather describing the iniquity awaiting the young man who seeks his fortune in the city:

Every form of sin and vice that human wickedness has invented, and every grade of evil-doers, from the juvenile thief to the hardened, desperate murderer, pour in there. On every side the emissaries of Satan watch for their victims, and throw around unsuspecting ones their galling fetters, and drag them down to shame.

Only a man as righteous as Amos Lawrence could withstand such temptations. And withstand them he did—or at least avoided them. Thayer admiringly quotes a delicately worded letter in which Lawrence recalled his first days in the city. “There was a part of Boston which used to be visited by young men out of curiosity,” he writes, “into which I never set foot.”

By the middle of the 19th century, the self-made man often was less a paragon of entrepreneurial ambition than a bulwark of virtue. In Thayer’s book, and in Charles Seymour’s biographical sketch in his omnibus, little space is devoted to Lawrence’s dry goods business. Lawrence worked hard, kept good books, and was trustworthy, so naturally his business thrived.21 (Seymour calls Lawrence “one of the most pure and lovely of all self-made men”—nice, but not exactly the stuff of a Harvard Business School case study.22) The focus, instead, is on the hero’s incorruptibility, which kept him out of “bar-rooms, gambling-houses, billiard-rooms, dancing-halls, club-rooms, theaters, and other dens of villainy.” Thayer might have added to his list soda shops, which, in an 1830 letter to his son, Lawrence accused of having “done more than anything else to debase and ruin the people of our city.”23

In Apostles of the Self-Made Man (1965), his history of the bootstrap myth, John G. Cawelti suggests that books like Thayer’s and Seymour’s constituted “a literature of reassurance rather than of inspiration and guidance,” an effort to allay concerns brought on by the social and economic upheaval that accompanied America’s rapid growth.24 That upheaval brought with it another concern: the growing ranks of the poor. As Scott A. Sandage documents in his study of American failure, Born Losers (2005), for every Amos Lawrence there were scores of anonymous Americans who tried to catch the rising tide of prosperity but couldn’t stay afloat. I saw them in Amos Lawrence’s charity diary: poor widows, poor sailors, a man who couldn’t make his rent, a man who couldn’t afford to buy shoes for his children.

But here, too, the self-made ideal proved useful: It functioned in this period as an explanation for success and for failure. If success was a function of a man’s good character, then failure must be evidence that his character was weak.25 Champions of the self-made man, therefore, could at once celebrate America’s equality of opportunity and explain away the inequitable results.

Even a man as charitable as Amos Lawrence had little sympathy for those who lacked his moral fiber, drawing a straight line from their spiritual failing to their worldly destitution. Silence was one of the virtues Franklin had tried to master in his self-improvement campaign, lest he lose precious time to “trifling Conversation.” Lawrence esteemed it as well. When he first moved to Boston, he asked the widow with whom he boarded to declare an hour of silence after supper for those who chose to study. The widow agreed. “The consequence was that we had the most quiet and improving set of young men in the town,” Lawrence wrote in a letter quoted by Thayer. “The few who did not wish to comply with the regulation went abroad after ten, sometimes to the theater, sometimes to other places, but, to a man, became bankrupt in after life, not only in fortune, but in reputation.” The failures, in other words, had no one to blame but themselves.

n the 19th century, the self-made man had an evil twin: the confidence man. Americans had to be on guard against those who sought to enrich themselves by preying upon the gullibility and greed of others. Amos Lawrence records in his diary a long line of applicants for his charity whom he deems frauds, or as he calls them, “wooden nutmegs.” Nineteenth-century success literature described a self-made man who accumulated his wealth slowly and steadily; he knew that his reward would come only through diligence. If any man promised to enrich himself or others minus the hard-work part of the equation, he was in all likelihood a charlatan. As Jackson Lears writes in his history of the Gilded Age, Rebirth of a Nation (2009), “The ideals embodied in self-made manhood, it was hoped, would diffuse throughout society and stabilize the sorcery of the marketplace, contain its carnival spirit.”

In Herman Melville’s dizzying satirical novel The Confidence-Man (1857), the titular character peddles sure-thing stock deals and subscriptions to fictitious charities on a Mississippi steamer. As the ship chugs down river, he appears in guise after guise, relieving his fellow passengers of their money while decrying the sad decline of trust among men. Melville offers a nightmare vision of the self-made success story. Unlike Benjamin Franklin, the runaway who reinvents himself as a printer, scientist, and statesman, or Amos Lawrence, the farm boy turned merchant prince, the confidence man remakes himself to fleece his next target. Melville turned the promise of American capitalism into a threat.

Horatio Alger Jr. wasn’t a confidence man, exactly. But the man whose name would become synonymous with the rags-to-riches story did reinvent himself as a means to leave behind a sordid past. Of all the tales that have shaped the self-made myth, Alger’s story is surely the strangest. Neither the man nor his fiction are what they seem to be.

Alger was born in 1832 and grew up in Chelsea, Massachusetts. His father was the minister of the First Congregational Church, a parish that had been organized by Cotton Mather.26 After graduating from Harvard, Alger tried his hand at the writing life, managing to get a few items published, but eventually followed his father into the seemingly more stable family business, landing an appointment to the Unitarian parish in Brewster, on Cape Cod.

As Gary Scharnhorst recounts in his scholarly biography,The Lost Life of Horatio Alger, Jr. (1985), Alger’s tenure in Brewster was short. A little more than a year after his arrival, rumors began to circulate that Alger had practiced “evil deeds” on a young boy. The parish convened a committee to investigate, which turned up evidence of further offenses “too revolting to relate.” Confronted by the committee, Alger “neither denied or attempted to extenuate” the evidence, “but received it with the apparent calmness of an old offender.” The young minister took the next train out of town.27

There followed a heated debate between the members of the Brewster church, several of whom understandably wanted Alger prosecuted, and the church’s Boston leadership, who were wary of calling attention to the crimes. In a letter to the church’s general secretary, Alger’s father begged the church not to go public:

The only desirable end to be gained by such publicity would be to prevent his further employment in the profession, and that I will guarantee that he will neither seek nor desire. His future, at the best, will be darkly shaded. He will probably seek literary or other employment at a distance from here, and I wish him to be able to enter upon the new life on which he has resolved with as little as possible to prevent his success.28

Alger had done “a serious injury to the church,” the general secretary ultimately decided, but “the injury is greater the wider it is known.”29 Provided Alger made good on his father’s promise never to re-enter the ministry, the church wouldn’t take further action. Alger moved to New York to seek his new life.

Unlike Amos Lawrence, who had been careful to avoid those sections of Boston that offered temptation, Alger spent his days mixing among the boys of New York City—specifically with the city’s “street Arabs,” the boys who had not become merchant princes but instead found themselves hawking newspapers or blacking boots and living in rundown boarding houses. “Alger began to haunt the docks and other sites where ‘the friendless urchins could be found,’ ” writes Scharnhorst, handing out to the boys candy or small sums of money. “These crude attempts at ingratiation succeeded,” he writes. “Alger’s room, first in St. Mark’s Place and after 1875 in various boarding houses around the city, became a veritable salon for street boys.”30

No reports of evil deeds surfaced from these boys; on the contrary, they felt a strong allegiance to their patron. “Mr. Alger could raise a regiment of boys in New York alone, who would fight to the death for him,” one of the boys told a reporter in 1885.31 Scharnhorst believes that after he left Massachusetts, Alger may have spent the rest of his life in repentant celibacy.32

Alger and his wards formed a symbiotic relationship. He provided them a refuge from the streets, and they offered up the details of their difficult lives, which Alger turned into the fiction that brought him the publishing success that had earlier eluded him. In 1868, he published Ragged Dick, the first novel to follow what would soon be recognized as the Horatio Alger formula and undoubtedly his best. The title character is a wise-cracking bootblack who, despite some bad habits (smoking, swearing, theatergoing) is in essence a reputable boy stuck in disreputable circumstances.

We think we know what comes next: Through hard work and perseverance, Ragged Dick emerges from destitution into a well-deserved fortune. But our contemporary notion of a “Horatio Alger story” departs significantly from what actually transpires in a Horatio Alger story. His heroes do exhibit many of the traditional self-made virtues—industry, frugality, a penchant for self-improvement—which set him apart from the ne’er-do-wells and confidence men who populate his adventures in the streets of New York. But these attributes merely qualify the Alger hero for success; they don’t produce it.

Instead, in Ragged Dick and in the scores of imitations Alger would write in its wake, the hero’s rise is the result of good luck and the good offices of a wealthy benefactor. In novel after novel, Alger’s hero meets a kindly gentleman who takes an interest in the poor boy’s advancement. He then buys the boy a new suit—a rite of passage into respectability that occurs in every story (often there’s a new watch, too)—and finds him a job, typically a junior position in a mercantile firm.33 Ragged Dick retires his boot-blacking kit when he’s offered a position as a clerk in the counting room of a Mr. Rockwell. He earns that position by saving Rockwell’s son, who conveniently falls off the Brooklyn ferry just as Dick’s penmanship has really started to improve.

Photo by Jacob Riis via Wikimedia Commons

It’s no surprise that Alger’s novels have disappeared from school curriculums and library shelves. There’s more narrative tension in an episode of Scooby-Doo than an Alger novel. Even a grade-schooler is liable to roll his eyes at the earnestness of Alger’s prose, the absurd plot contrivances that move the stories along, and the dumb luck that wins the hero his respectable employment. What is surprising is that the books remained popular for as long as they did. Shortly before his death in 1899, Alger estimated that he’d sold around 800,000 books in his lifetime, an impressive total for the era. But it was nothing compared to what was to come. “By 1910, his novels were enjoying estimated annual sales of over one million,” writes Scharnhorst. “That is, more were sold in a year than were sold in total during his life.”34

There are various theories as to why Alger enjoyed such posthumous regard. Scharnhorst notes that cheap editions of the novels flooded the market between 1899 and 1920, many of them “silently abridged.” These versions had as many as seven chapters excised, often those from the beginning of the books, which typically described the virtuous deeds that marked the hero as worthy of the good luck that was inevitably around the corner. “In effect,” writes Scharnhorst, “Alger’s work was editorially reinvented to appeal to a new generation of readers. Whereas in his own time Alger was credited with inventing a moral hero who becomes modestly successful, during the early years [of the 20th century] he seemed to have invented a successful hero who is modestly moral.”35 In the wake of the Gilded Age’s excesses and depredations, a self-made man who was anything more than modestly moral might have been less believable than a young man elevating his station by fishing a boy out of New York Harbor.

Like Franklin’s, Alger’s contribution to the self-made mythology was thus only partially of his own design. The hopes—and anxieties—of a new group of readers molded the story to suit that generation’s needs. It was only later still, when readers stopped reading Alger altogether and moved on to new avatars of the self-made man, that a hazy memory of his adumbrated fictions led Americans to make his name a shorthand for a rags-to-riches story that Alger neither lived nor told.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

ne day in the late 1850s, Andrew Carnegie boarded a train in Altoona, Pennsylvania, bound for Ohio. About 25 at the time, Carnegie was working as an assistant to Tom Scott, who would eventually rise to the presidency of the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad and was currently serving as its superintendent. Carnegie was in the rear car, looking out the window, when “a farmer-looking man” approached him. The farmer-looking man, who was carrying a mysterious green bag, had been told that Carnegie worked for the railroad, and he asked the young man for a moment of his time. Carnegie assented, and the man produced from his green bag a small model of his invention: the sleeper car.

“Its importance flashed upon me,” Carnegie would later recount in his Autobiography. “I asked him if he would come to Altoona if I sent for him, and I promised to lay the matter before Mr. Scott at once upon my return. I could not get that sleeping-car idea out of my mind.”36 When he arrived back in Altoona, Carnegie was as good as his word, pressing the idea on Scott, who ordered two of the sleeper cars. Carnegie telegraphed the good news to T.T Woodruff, the inventor, who was so overjoyed with the news that he offered the young man an eighth interest in his company. “The first considerable sum I made was from this source,” Carnegie writes.

It’s a scene straight out of Alger. The young man respectfully hears out an ostensible hayseed, only to discover this older fellow is in fact the creator of a “now indispensable adjunct of civilization,” in Carnegie’s words. The young man having proven his kindness, and his ability to recognize and facilitate a promising venture, the older gentleman rewards him with an act of largesse. Carnegie, the immigrant son of a failed weaver, was set on the path to prosperity by the sturdy Alger formula: luck and pluck.

It’s a great story, but as David Nasaw, Carnegie’s biographer, writes, it doesn’t happen to be true.37 By the late 1850s, Nasaw points out, T.T. Woodruff wasn’t a rube in need of a railroad clerk’s help selling his idea, but a “successful inventor who had already secured contracts for his sleeping car with several railroads, including the Pennsylvania.” Far from being the prime mover in the deal, Carnegie’s role had been minor, and hardly one worth bragging about. Before signing an agreement with Woodruff, Scott and fellow Pennsylvania Railroad executive J. Edgar Thomson demanded a kickback, in the form of partial ownership of the company. “To disguise their stake,” Nasaw writes, “they requested that their stock be put in Andy Carnegie’s name. For his troubles, Andy was given a few shares himself.”38In short, what in Carnegie’s telling had seemed like bootstrapping at its finest turns out to be mere crony capitalism.

Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the Gilded Age, the lofty ideals of self-made manhood would sit uncomfortably beside the realities of an industrial economy that threatened to expose economic mobility as a myth. On the one hand, the two richest men in America, Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, were self-made men (Rockefeller’s father was a confidence man, a peddler of elixirs) who stood fast by the idea that determined men would surely rise. “The opportunities are greater today than they have ever been before and no boy, the humble newsboy, the child of the tenement—need despair,” said Rockefeller. “I see in each of them infinite possibilities. They have but to master the knack of economy, thrift, honesty, and perseverance, and success is theirs.”39 In the lecture “The Road to Business Success: A Talk to Young Men,” Carnegie told his audience that there was plenty of room at the top, and the best way to get there was to start at the bottom. “If by chance the professional sweeper is absent any morning,” he told aspiring captains of industry, “the boy who has the future partner in him will not hesitate to try his hand at the broom.”

And yet, the real captains of industry didn’t practice what they preached. Carnegie goes on in his lecture to inveigh against the practice of speculation. “Gamesters die poor,” he said, “and there is certainly not an instance of a speculator who has lived a life creditable to himself, or advantageous to the community.” But as Nasaw documents, Carnegie himself had made massive profits in the years before he entered the steel industry “by doing precisely what he would later condemn: buying and selling shares in companies whose assets he knew were worth far less than the value of their stock.”40

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Whether or not the boys listening to Carnegie’s speech knew the specifics of his deceits, the idea of an equal-opportunity America had become more difficult to sustain in an era when massive amounts of capital had been concentrated in the hands of a few industrial titans. Just as tenuous was the idea that thrift and perseverance were sufficient to open up Rockefeller’s “infinite possibilities.” As Nasaw asks, who worked harder than the steelworker? (Especially a steelworker at one of Carnegie’s plants, where he andHenry Clay Frick had crushed union opposition to the 12-hour workday.) Toil as he may, the steelworker’s chances of advancement seemed vanishingly small. Meanwhile, the violent crashes that punctuated the Gilded Age—a function, in part, of the era’s rampant financial chicanery—consigned plenty of industrious, abstemious men to poverty.

In this climate, the self-made man started to look more villainous than heroic. John Cawelti points to T.S. Denison’s pithily titled 1885 novel An Iron Crown: or, Modern Mammon. A Graphic and Thrilling History of Great Money Makers and How They Got Millions. Both Sides of the Picture—Railway Kings, Coal Barons, Bonanza Miners and Their Victims. Life and Adventure From Wall Street to the Rocky Mountains. Board of Trade Frauds, Bucket-Shop Frauds, Newspaper Frauds, All Sorts of Frauds, Big and Little. The book’s central characters were self-made men, Cawelti writes, “but some of them arrive at their wealth by dishonesty, corruption, speculation, and monopoly, while others follow the traditional path of honest industry. In terms of financial accumulation, the former are infinitely more successful.”41 Denison wasn’t ready to abandon the self-made ideal, but he knew that the men who made the most were not the ones who played by Poor Richard’s rules.

Other men turned to the self-made captains of industry for help. As Scott Sandage writes in Born Losers, the Gilded Age birthed a new genre of writing: the begging letter. Thousands of men (and women, though they were usually writing on behalf of their husbands) wrote to Rockefeller and Carnegie seeking a job or financial assistance, and their letters reveal a mounting ambivalence about the self-made mythology. Fitch Raymond, a bankrupt grocer, writes to Rockefeller that he has been “Struggling incessantly” to get back on his feet, “but the trouble is, I have no capital with which to make a start, & it is utterly impossible to make something out of nothing.”42 Andrew Osborne, a failed inventor, writes to Rockefeller asking for a job, presenting himself as possessing all the qualities of a self-made man in the making—if he could just find someone to give him that first push:

Here is a young man ambitious to try to get up the ladder ... and who if given the chance, might and with his Yankee courage and grit, would in a short time place him self right before the business world. ... My motto is and shall be where there is a will there is a way.43

Neither Raymond nor Osborne had given up on the values that supposedly led to self-made success, but they argued that those values alone were proving insufficient to get ahead. The authors of begging letters, Sandage writes, “believed in working their way ‘up the ladder,’ but at the same time they understood that forces larger than individual aptitude spawned self-made men and broken men.” Success or failure was a matter of luck, not pluck. “You have been fortunate,” one man wrote to Rockefeller. “I have been unfortunate.”44

As Sandage notes, the authors of begging letters “asked neither for alms nor abundance; they asked for a chance to strive again.”45 Despite their struggles, these men wanted back into the game. The triumphant narrative of the self-made man needed to adapt its message to these more parlous times. A new self-made man emerged, one whom Benjamin Franklin and Amos Lawrence might have been frightened to behold. He wasn’t a scoundrel, exactly, but in the Gilded Age the ends fully justified the means—the self-made man was the man who had the drive, confidence, and single-mindedness to pursue wealth, no holds barred.46

John Graham was an exemplar of the new bootstrapping industrialist, no less so for being the invention of George Horace Lorimer, the editor of the Saturday Evening Post. The Post, which (spuriously) traced its lineage back to Benjamin Franklin’s newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, was one of several publications geared to middle-class readers eager to improve their station.47 In Letters From a Self-Made Merchant to His Son, first a popular magazine column and later a book, Lorimer took on the voice of Graham, a hard-charging pork tycoon modeled on his own former boss, the meatpacking robber baron Philip Armour.48 Graham articulated the new self-made ethos in a series of entertainingly exasperated letters to his feckless son Pierrepont, who, having grown up in the comfortable circumstances his father’s success provided, is showing signs of softness. In just the first few letters, Graham is forced to disabuse his son of the idea of attending graduate school, embarking on a European tour, and writing letters to young women. Instead, he installs his son as a clerk in the mailroom of Graham & Co. Like Carnegie, Graham believes in starting at the bottom, even if you’re the boss’s son.

In his exhortations to his son, Graham offers a glimpse of a new self-made man: “You’ve got to have the scent of a bloodhound for an order, the grip of a bulldog on a customer. You’ve got to feel the same personal solicitude over the bill of goods that strays off to a competitor as a parson to a backslider, and hold special services to bring it back into the fold.” If you’re going to run Graham & Co. one day, Graham tells Pierrepont, “you’ve got to add dynamite and ginger and jounce to your equipment.”49

Never mind the young ladies, in other words—the pork business should give your equipment charge enough. And nothing should get in the way of landing the account. “Religion, politics, ethics, all fall into line as adjuncts to success in the pork-packing business,” John Cawelti writes in his typically astute analysis of Letters From a Self-Made Merchant, “and the individual becomes whatever he has to be to win and keep the customer.”

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

As for the dwindling number of opportunities in America, the Gilded Age defenders of the self-made ideal had an answer to that charge, too: Men who failed to find opportunity were looking in the wrong places. The most famous articulation of this argument was Russell Conwell’s “Acres of Diamonds” lecture, which he delivered more than 6,000 times—enough to make himself a not-so-small fortune. (He went on to found Philadelphia’s Temple University.) The speech opened with a parable, supposedly told to Conwell by an “old Arab guide” while traveling down the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, about a Persian farmer who spends his life in a fruitless search for diamonds, never realizing that his own untended farm is rich with the gems. Conwell told his audience that there were acres of diamonds in their backyards as well—they just needed to stop complaining and start digging. “There was never a place on earth more adapted than Philadelphia to-day, and never in the history of the world did a poor man without capital have such an opportunity to get rich quickly and honestly as he has now in our city,” he said, adjusting the text accordingly when he took his speech on the road.

What followed in the lecture were stories about self-made men (and even a few self-made women) who had earned millions by finding an opportunity and seizing it: the man who invented the safety pin; the man who invented the pencil eraser; the woman who had attended Conwell’s lecture, found herself frustrated with her collar button, and invented a superior version with a spring cap. Her fortune had, quite literally, been “right under her chin.”

Conwell was short on practical advice, but the accumulated examples made their point—it wasn’t a lack of opportunity holding Americans back, but a lack of ingenuity. “I do not believe there is one in ten of you that is going to make a million of dollars because you are here tonight,” he told his audience. “But that is not my fault, it is yours.”

The Puritans had believed that it was man’s duty to do good and that earthly riches would be his reward. Conwell reversed the order of operations. He taught that it was man’s duty to get rich, then to do good with the proceeds. “Money is power and you ought to be reasonably ambitious to have it. You ought to because you can do more good with it than you could without it,” he told his audiences.

Here Conwell was preaching a version of an idea made famous by Andrew Carnegie, in his The Gospel of Wealth. It was the duty, Carnegie wrote, of wealthy men to see that their money was put to good public use. The Gospel of Wealth was at once a grand philanthropic creed and a transparent rationalization of the system that had concentrated such vast resources in the hands of just a few men. The man of wealth, Carnegie wrote with breathtaking condescension, was “the mere trustee and agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could for themselves.”

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Here was Carnegie, who had ruthlessly fought to depress wages and extend hours at his steel mills, writing passionately about the need to administer to the community. Passionately and also sincerely, to judge by the massive sums of money he gave away, though all of it according to a plan designed to encourage the ambitious and discourage the man looking for a handout. “It were better for mankind that the millions of the rich were thrown into the sea than so spent as to encourage the slothful, the drunken, the unworthy,” he wrote. To avoid this outcome, Carnegie gave to institutions he believed would facilitate the rise of the next generation of self-made men: He endowed libraries, colleges, museums, and concert halls where men might cultivate an appreciation of the arts, as he had. “In his mind,” writes biographer David Nasaw,

there was still abundant opportunity for upward mobility: from manual wage work to foreman to department head to supervisor. He understood—how could he not?—that his laborers were underpaid. But he believed that those who were worthy would quickly transcend that status. They would study and learn—in his own libraries, no doubt—and rise steadily.50

It seems like an illusion only a self-made magnate like Carnegie could maintain. But in 1901, no less a Brahmin than the Episcopal Bishop of Massachusetts gave the idea his imprimatur.51 “To seek for and earn wealth is a sign of a natural, vigorous, and strong character,” he said. As for the rich man who supports charity, he “is Christ’s as much as was St. Paul, he is consecrated as was St. Francis of Assisi. ... If ever Christ’s words have been obeyed to the letter, they are obeyed to-day by those who are living out His precepts of the stewardship of wealth.”

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The bishop who wrote this sermon was William Lawrence, Amos’ grandson. In a sense, his remarks merely ratified the practices of his munificent grandfather, who’d made a project of giving away his wealth well before Andrew Carnegie was born. But in his ringing endorsement of the pursuit of wealth—“godliness is in league with riches,” he declared—William sounded less like he was honoring the man who handed out his hard-won dollars to widows and sailors, and more like he was flattering his friend and fellow son of privilege J.P. Morgan. William Lawrence had tapped Morgan to help him raise $5 million for his church’s pension fund, and later persuaded him to manage it. In the Gilded Age, even men of the cloth were dealmakers.

“I had just completed my thirteenth year and I fairly panted to get to work that I might help the family to a start in a new land,” Andrew Carnegie recounts in his Autobiography. Carnegie’s father had brought the family over from Scotland, in the hope of finding more lucrative work in the textile trade, but he had thus far been no more successful in Pittsburgh than he’d been in Dunfermline. The family needed money, and Andrew would soon secure his first job, running a small steam engine in a bobbin factory for $2 a week. Later, he would be assigned the task of dipping the bobbins in vats of oil, the odor of which left him green with nausea. Fortuitously for Carnegie, his uncle had a regular checkers game with the manager of Pittsburgh’s telegraph office, a Mr. Brooks, who inquired one night if he knew of a boy who might make a good messenger. It would be an opportunity for Andrew to leave behind the menial labor of the factory for an office job, one that would bring him into contact with men of business. “Upon such trifles do the most momentous consequences hang,” wrote Carnegie of that checkers game, with typical humility. “A word, a look, an accent, may affect the destiny not only of individuals, but of nations.”52

Carnegie’s father insisted on accompanying the boy to his interview, but when they arrived at the telegraph office, Andrew asked to go up to the office alone. “I was led to this, perhaps, because I had by the time begun to consider myself something of an American,” writes Carnegie. “In speech and in address the broad Scotch had been worn off to a slight extent, and I imagined that I could make a smarter showing if alone with Mr. Brooks than if my good old Scotch father were present, perhaps to smile at my airs.” His father relented; Andrew got the job.

For the immigrants who came to America a few decades later as part of the great wave at the turn of the century, finding the path to prosperity wasn’t so easy. An Eastern European Jew or Southern Italian probably didn’t have an uncle who played draughts with the local Mr. Brooks, and passing as an American wasn’t as simple as swallowing your brogue. And yet it was this wave of immigrants who would ultimately take up the self-made mantle: the belief that anyone—even a new arrival with no money, no home, and no command of the English language—can make something of themselves on these shores, provided he’s willing to work.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

As Jeffrey Louis Decker notes in his lucid study Made in America: Self-Styled Success from Horatio Alger to Oprah Winfrey (1997), one of the great champions of the immigrant as rightful heir of the self-made ideal was Mary Antin. A Jew from the Pale of Settlement, Antin’s family emigrated to the U.S. in 1891, settling in Chelsea, Massachusetts. In her tract They Who Knock at Our Gates: A Complete Gospel of Immigration, Antin compared the new arrivals from the Pale with the Puritans who arrived at Plymouth Rock in 1620. Only the latter-day pilgrims had overcome even greater persecution: “It takes a hundred times as much steadfastness and endurance for a Russian Jew to remain a Jew as it took for an English Protestant in the 17th century to defy the established Church.”

Great wave immigrants like Antin and her contemporaries molded the bootstrap myth to their own experiences. Louis Borgenicht, another Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe, arrived in New York with no capital and no prospects and found himself in a world foreign and inhospitable. “The Statue of Liberty was fine,” reads the opening sentence of Borgenicht’s memoir. “Everything else formed a succession of hammer blows to the face,” reads the second.53

Early 19th-century farm boys had been admonished to steel themselves against the city’s temptations of the flesh; early 20th-century immigrants found barely enough sustenance to survive—they were ascetics by harsh necessity. Of the denizens of the Lower East Side, where the Borgenichts, like many great-wave immigrants, settled, Louis writes:

These were not people—polite, quiet—but ravening wolves, lost to all decency as they snarled over bones. … Their eyes held the dream. But I saw that their bodies were thin and tired, wrapped in shapeless bundles to keep out the cold. Around them rose filthy firetraps. In the streets lay stinking garbage. Packed up like chickens in piled crates, these people lived and worked.

The conditions demoralize Borgenicht, but the industry he sees wherever he turns inspires him. “These people worked. That’s what I came here for—to work, to slave.” With Franklin-esque diligence, he sets about finding a trade, and with Franklin-esque ridiculousness makes several false starts, failing as an overly theatrical herring hawker and pushcart man before realizing his best prospect is to return to the garment work he’d done in Europe, where he’d been a piece-good merchant. He spends a week studying the clothing of the men, women, and children of New York. In a Slavic neighborhood, he happens upon a young girl wearing a small apron over her dress, of a type he recalled from central Europe but had rarely seen in America. “They were useful, tidy, decorative,” Borgenicht writes. He’d found the item that would launch his enterprise. Investing what few dollars he’d accumulated in a bolt of gingham, he and his wife Regina cut and sew 40 aprons. Taking them to the street the next day, he sells all 40 by lunchtime.

On the back of this initial success, Borgenicht builds a thriving enterprise, with a manufacturing space and employees of his own. Early on, he discovers an inefficiency in his trade. He’s been forced to buy his fabric from a so-called jobber, a middleman who takes a cut for his services, thereby increasing the cost of materials. Borgenicht realizes that if he could buy directly from the commission houses that sold on behalf of the mills, he would increase his profits. “A simple proposition,” he writes. “But it was a novel adventure at the time.”

He secures a meeting with one the biggest commission houses in the East. Sitting down with a Mr. Bingham, “a white-bearded Yankee” with steel-blue eyes, he makes his proposal. Borgenicht recounts the scene that followed:

“You have a H---- of a cheek coming in here and asking me for favors!” [Bingham] said. “Why should I do it?”

That was the question I had hoped for.

I launched into an explanation of my position and prospects. Honest, hard-working, dealing with fine customers, I was a cinch to make good if Bingham would help me. I put every ounce of conviction into my plea, I spoke from the heart.

“You still have a H---- of a cheek,” he said—and then he smiled. “We’ll do it!”

Bingham’s firm was Lawrence & Co., founded by Amos Lawrence’s son—Bishop Lawrence’s father—in 1843. The Yankees no longer had a monopoly on the self-made ideal.

The success of men like Borgenicht increased the diversity at the American church of success, but it hardly swung open the doors to one and all. On the contrary, as the immigrant success story became the dominant strain of 20th-century self-made mythology, it had a tendency to exclude as many congregants as it welcomed. The achievements of certain disadvantaged groups (Jews, say) and the continued struggles of others (for instance, blacks) led to pernicious assumptions about the stuff each group was made of. Those who found a way to emerge from the ghetto were said to possess the correct cultural values. Assessing the success of Jewish immigrants, the scholar Milton Gordon attributed it to the fact that “the Jews arrived in America with middle-class values of thrift, sobriety, ambition, desire for education … already internalized.”54 The sociologist Stephen Steinberg has called this line of thinking “the Horatio Alger Theory of Ethnic Success”—ascribing the traditional self-made virtues to an entire people.55

As Steinberg points out, among the problems with the Alger approach is that it wrongly presumes that all immigrant groups started out with the same disadvantages. In fact, as Steinberg shows in The Ethnic Myth(1981), the Jews who arrived as part of the great wave had a leg up on many of the groups with whom they lived cheek-by-jowl—and it wasn’t a superior dose of industry, sobriety, or ambition. Because Jews had for centuries been prohibited from owning land in Europe, they had long since migrated to cities, and to urban trades and professions.56 A disproportionate number of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe thus arrived in the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with years of “industrial experience and concrete occupational skills that would serve them well in America’s expanding industrial economy,” Steinberg writes.

If Louis Borgenicht’s name sounds familiar, it’s likely because you recall it from Malcolm Gladwell’sOutliers, in which he has a walk-on role. Having put in his 10,000 hours of garment work—or a healthy portion of it—in Polish Galicia, Borgenicht was poised to thrive in the exploding clothing industry in downtown Manhattan. That’s no knock on Borgenicht’s evident work ethic. The old virtues alone, however, might not have saved him from the Lower East Side’s ravening wolves. He also needed a little of what Cotton Mather called grace, Horatio Alger called luck, and Stephen Steinberg calls socioeconomics.

he current line from online fashion retailer Nasty Gal includes a polka-dotted mesh garter belt slip (“wear it with the matching bralette and thigh highs for your boo”), a knee-high boot made largely of chain link, and a $38 T-shirt with “Ryan Gosling Broke My Heart” written across the front in the jagged bubble letters of a spurned tween diarist. We’re a long way from tidy aprons. But if Louis Borgenicht wouldn’t know what to make of Nasty Gal’s wares, he’d surely admire the company’s chutzpah. With no more capital than Borgenicht had when he arrived in New York, Nasty Gal’s founder Sophia Amoruso built a company that does upward of $100 million in annual sales—and she did it in a mere eight years.

Nasty Gal began as an eBay store, where Amoruso would auction off vintage clothing she found at estate sales and Bay Area thrift stores. Storing her inventory in Rubbermaid bins, she ran her one-woman operation out of a rented pool house that doubled as her home. The business plan was hardly novel, nor did it promise to be lucrative, but Amoruso found she had a knack for anticipating buyer demand and for stoking that demand in her listings. At the time, in the mid-aughts, most of eBay’s vintage retailers haphazardly draped their items over a limp hanger or headless mannequin. Amoruso recruited models to wear her disco gowns and Golden Girls tracksuits, styling and photographing them for maximal impact in the tiny thumbnail images that can make or break an auction. She also tapped into the nascent power of social media, building a network of potential customers by friending “it-girls” on MySpace. In 2007, she shuttered the eBay store and opened an independent site, selling a combination of vintage and contemporary items. In its first full year, Nasty Gal had revenues of $223,000. By 2011, that number was $23 million.

Nasty Gal’s exponential growth, then and since, has made its founder a darling of the business press. Amoruso has been profiled in Entrepreneur, Forbes, and Inc., which last year included her on its list of 30 under 30, when she was 29. This spring, she published her own account of her rise from rag house to riches, #Girlboss; it's since been a fixture atop Amazon's “Business Motivation and Self-Improvement” category, and a New York Times best seller. Amoruso writes in an informal, distractible voice that might best be described as Gchat-y—“I made the chapters intentionally short so people felt accomplished when they finished one,” she told me recently, calling from Cannes, where she’d just spoken at a Google event—and with a degree of candor that can occasionally verge on TMI. (The unlikely role a groin hernia played in her career is not overlooked, nor is the effect it had on her personal grooming choices.) But the book’s informal tone belies a serious purpose: to restyle the virtues of the vintage self-made man for the millennial woman.

Despite the hashtag in its title, #Girlboss is a surprisingly traditional self-made narrative. Like Franklin, Amoruso explains that she is offering her story in the hope that her success might be emulated by her readers—in her case, the “girlbosses” of tomorrow, to whom the book is explicitly addressed—and she foregrounds her rise by dwelling on her low beginnings. Her parents, who worked in home loans and real estate, filed for bankruptcy when she was 10 and expected their daughter to provide for herself from an early age. Her first job was as a Subway “sandwich artist,” an experience she returns to throughout the book, sparing no embarrassing detail. In place of Franklin’s penny rolls, she conjures the image of her teenage self, in corporate polo and visor, scooping tuna salad onto a $5 footlong. “Part of my job was to wear gloves and massage mayonnaise into the tuna,” she writes. “Sexy!”

From Subway, Amoruso bounced from job to unenviable job, selling orthopedic shoes, scrubbing stains out of men’s collars at a dry cleaner, manning the security desk at a community college. But in a chapter titled “Shitty Jobs Saved My Life,” she credits this string of dead-end positions with instilling the industriousness that has always been the core value of the self-made man, which she now claims as the cardinal virtue of the girlboss. “If you’re a #GIRLBOSS, you should want to work harder than everybody else”—and be prepared to do whatever work is demanded of you. “What all these jobs taught me is that you have to be willing to tolerate some shit you don’t like. In an ideal world you’d never have to do things that are below your position, but this is not an ideal world and it’s never going to be.”

In a sense, this is a recapitulation of Carnegie’s gospel of sweeping, though Amoruso learned it from her Greek-American family, not the Scottish-American steel man. (Her father’s advice: “Show up. Don’t stop moving. Sweep the floor even when they don’t ask you to.”) But by lingering over her run of menial jobs, Amoruso also brings to the self-made narrative a 21st-century reality check, acknowledging that a willingness to grab a broom doesn’t guarantee a quick ascent. Despite their meager beginnings, Benjamin Franklin and Andrew Carnegie soon found the employments that would launch their careers. In a sputtering economy, and one that still provides greater opportunity for men than women, an aspiring girlboss might need to grasp the bottom rung of several different ladders before she finds the one she can climb.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Or she might need to build her own. Amoruso never mentions Sheryl Sandberg in #Girlboss; instead, she ruthlessly subtweets the Lean In author, proudly holding up her scrappy entrepreneurialism as a contrast to Sandberg’s path of privilege from Harvard to the Treasury Department to the C-suites of Google and Facebook. “I didn’t come from money or prestigious schools, and I didn’t have any adults telling me what to do along the way,” Amoruso writes. “I figured it out on my own.” Without the benefit of an Ivy League education or a Cabinet-level mentor, Amoruso built a thriving business—one in which the girl in the Aloha Bitches sweatshirt, not a boy in a hoodie, occupies the corner office.

Amoruso offers some perfunctory advice to young women who want to work their way up through a corporate org chart—spell-check your cover letter; wear a bra to your interview—but she’s content to leave the plight of women in the workplace to others. “I believe the best way to honor the past and future of women’s rights is by getting shit done,” she writes, in another none-too-subtle dig at Sandberg. “Instead of sitting around and talking about how much I care, I’m going to kick ass and prove it.” Amoruso’s ambition isn’t to add another crack to the glass ceiling; it’s to carve out a place for women in the heroic American narrative of entrepreneurship.

That narrative, of course, is still dominated by men. Last year, Entrepreneur featured Amoruso in its list of “Entrepreneurial Women to Watch,” a feature that opened with a lament for its very existence:

We can only hope that one day soon there'll be no reason to single out women as a specific category when we look at up-and-comers in the world of business. But the current reality is this: While the number of U.S. companies owned by women is increasing faster than those of other groups, those companies are responsible for just 6 percent of the country's employees and 4 percent of revenue.