The Biggest Mass Lynching In The United States, L.A., 1871 (Correcting My Error)

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2017/04/the-biggest-mass-lynching-in-united.htmlAlan: Since posting the article below in 2014, it has come to my attention that the largest mass lynching in the United States actually took place in 1871, resulting in the death of 17 to 20 Chinese angelinos:

http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2017/04/the-biggest-mass-lynching-in-united.html

Summary:

On the night of October 15, 1890, in New Orleans, Louisiana, the Chief of Police, David Hennessy, was shot down in the street. A former policeman heard the shots and rushed to his side. When asked who shot him, Hennessy allegedly answered, "A dago." "Dago," according to this report, "was a derogatory word used to describe an Italian day laborer."

By the late 1800s, the French Quarter area of New Orleans had become known as "Little Palermo," dominated by successful merchants and restaurant owners who had immigrated from Sicily. Their achievements ignited racial tensions.

Many Sicilians worked as fishermen in New Orleans and were viewed as taking work away from the Irish, who had run the waterfront. As in other cities, they could not break into the jobs held by Irish immigrants on the police and fire departments and because they were the newest group of immigrants and their customs were very different from Irish customs, there was considerable tension between Irish and Italians everywhere. Italians were also widely considered to be non-white.

By the time of Chief of Police David Hennessy's murder, there was a great deal of hatred in New Orleans directed at the Italians, and not only by the Irish. Newspaper cartoons portrayed Italians as dirty, lazy, illiterate, and dangerous. A newspaper headline proclaimed "Superintendent Hennessy Shot Down by a Dago Gang."

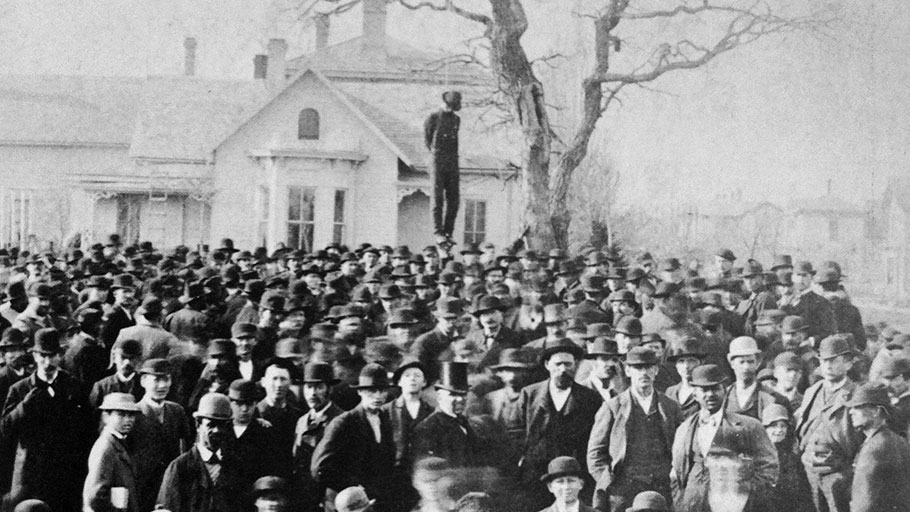

300 Italian-Americans were rounded up. Nine men were eventually tried and acquitted of the murder. A mob of thousands broke into the prison and dragged the acquitted men into the streets. A total of eleven Italian-American men were lynched that day.

By the late 1800s, the French Quarter area of New Orleans had become known as "Little Palermo," dominated by successful merchants and restaurant owners who had immigrated from Sicily. Their achievements ignited racial tensions.

Many Sicilians worked as fishermen in New Orleans and were viewed as taking work away from the Irish, who had run the waterfront. As in other cities, they could not break into the jobs held by Irish immigrants on the police and fire departments and because they were the newest group of immigrants and their customs were very different from Irish customs, there was considerable tension between Irish and Italians everywhere. Italians were also widely considered to be non-white.

By the time of Chief of Police David Hennessy's murder, there was a great deal of hatred in New Orleans directed at the Italians, and not only by the Irish. Newspaper cartoons portrayed Italians as dirty, lazy, illiterate, and dangerous. A newspaper headline proclaimed "Superintendent Hennessy Shot Down by a Dago Gang."

300 Italian-Americans were rounded up. Nine men were eventually tried and acquitted of the murder. A mob of thousands broke into the prison and dragged the acquitted men into the streets. A total of eleven Italian-American men were lynched that day.

***

ANTI-ITALIAN MOOD LED TO 1891 LYNCHINGS Times Picayune Newspaper March 14, 1991 Page B1 Submitted by Larie Tedesco

Late on the night of Oct. 15, 1890, as New Orleans Police Chief David C.

Hennessy walked to his Girod Street home, he was ambushed by a group of men

who had been hiding in a shanty across the street. He died the following

morning, conscious until the end, and explicit about who had done him in:

"Dagoes."

The killing, and the sinister events that followed, capped a period of

profound anti-Italian sentiment in the city, which had been building during

three decades of heavy Italian immigration. It culminated on March 14, 1891,

when the largest mass lynching in American history took place in New Orleans.

The saga began when Joseph A. Shakspeare, then mayor, appointed Hennessy as

police chief. Hennessy had gained a national reputation for the capture of a

Sicilian bandit named Esposito, who was credited by some with bringing the

Mafia to the United States. The Mafia was believed to be responsible for

nearly 100 unsolved murders in New Orleans since the Civil War, and Hennessy

was determined to eradicate it. He was greeted by a code of silence in the

Italian community.

While Hennessy's elaborate funeral proceeded, a dragnet led to the arrest of

dozens of Italians. Meanwhile, the business and political community responded

to the assassination with outrage and created a well-financed "Committee of

Fifty" to help indict and convict the alleged assassins. This extra-legal

group included public officials, lawyers, newspapermen, bankers, and

businessmen, and was led first by Edgar H. Farrar and then by Walter C. Flower.

Eventually, 19 Italians were indicted on charges of Hennessy's murder and nine

of them were tried in February 1891. They retained some high-priced legal

talent, including the colorful private detective Dominick C. O'Malley, one of

Hennessy's enemies.

The alleged masterminds of the conspiracy were Charles Matranga and Joseph P.

Macheca, the latter a prominent merchant and political leader who was once a

friend of Hennessy's. Pietro Monasterio lived in the shanty from which the

attack was launched. The suspected gunmen were Antonio Scaffidi, Antonio

Bagnetto, Emmanuele Polizzi, Bastian Incardona, and Antonio Marchesi. Also on

trial was Marchesi's teen-age son Gaspare Marchesi, who allegedly had used a

whistle to warn the assassins of Hennessy's approach.

During the trial, Polizzi raved maniacally and made a confession, which was

not admitted into the record. Indeed, several key witnesses were never called

to testify. Despite such lapses, most New Orleanians strongly believed in the

merits of the case.

So the city was stunned on the afternoon of March 13, when six of the

defendants were found innocent and a mistrial was declared in the cases of

three others. Talk of jury tampering, intimidation, and bribery was rampant.

Because there were still some outstanding indictments, all the defendants were

returned to prison.

That evening, a large group of men dissatisfied with the verdict met. Among

its leaders were Farrar, William S. Parkerson, Walter D. Denegre, John C.

Wickliffe, James D. Houston, and Charles J. Ranlett. The 61-man Vigilance

Committee placed an ad in the next morning's newspapers calling for a meeting

and warning participants to "come prepared for action."

Thousands of people responded and met at the statue of Henry Clay on Canal

Street to hear Parkerson: "When the law is powerless," he said, "rights

delegated by the people are relegated back to the people, and they are

justified in doing that which the courts have failed to do." The speakers left

little doubt that bloody work was to be done that day.

Reportedly, the plan was to take six of the men from the prison and execute

them in view of the citizens of New Orleans. The other three were to be

spared.

Sensing danger, the Italian consul in the city, Pasquale Corte, sought help

from Gov. Francis T. Nicholls, who said he could do nothing without a request

from Mayor Shakspeare, who was holed up in the Pickwick Club.

The crowd marched to Parish Prison, near the site of the present-day Municipal

Auditorium. Refused admittance at the front gate, the leaders gained access

through a back door. Several dozen others barged in and added to the

confusion.

Unable to protect the Italians from the mob, the jailers let them loose within

the walls to fend for themselves, but nine of them - including five who had

not been brought to trial - were chased down and shot. Two others were dragged

outside and forced through a kicking gauntlet to a tree.

One was hanged from a rotten branch, and when it snapped, he was hanged in

short order from a sturdier one. The other suffered worse agonies. He was

hanged from a lamppost by a rope that broke and brought him tumbling to the

ground. He was hoisted again, but since his arms had not been tied, he grabbed

the line and pulled himself up to the crossbar. A blow to the face sent him

dangling once more, but he again grabbed the line. Lowered into the crowd, his

hands were bound and he was hauled up a final time. A half-dozen bullets put

an end to his writhing.

When it was all over, 11 men who had not been found guilty of any crime were

dead. Those responsible for the deaths proclaimed their action was a success

and justice had been done.

The city's business community and the daily newspapers supported the

lynchings. A survey showed that 42 of the nation's newspapers approved of the

action, while 58 disapproved. A grand jury indicated that if there was guilt,

it was shared by the entire mob, estimated at between 6,000 and 8,000 people.

The Italian government protested, and there was even talk of war. Though the

United States accepted no responsibility, it did pay an indemnity to the

survivors of those victims who held Italian citizenship.

The lynchings didn't eradicate organized crime from the city, nor did they put

an end to other theories of "Who Killa da Chief?" - as the next generation or

two of Italian-Americans were taunted. Neither did it slow Sicilian

immigration into New Orleans. In time they, like other immigrant groups, were

assimilated into the mainstream of American life with members of their large

community rising to prominence in all areas of endeavor.

http://files.usgwarchives.net/la/orleans/newspapers/00000077.txt

***

Linciati: Lynchings of Italians in America (2004)

Linciati: Lynchings of Italians in America (2004) Unlike other European immigrants who struggled initially to become “white” in America, such as the Irish and the Jews, Italian immigrants fought a hostile reception even beyond the third generation in the U.S. Despite or perhaps because of the nearly quintessential American families of the Corleones and the Sopranos, young people of Italian descent are still given affirmative action scholarships, at least in New York City, to entice them to fo to college and take part in the American Dream. Although European immigrants were initially granted automatic citizenship thanks to the privileging of white skin that inspired the Naturalization Act of 1790, thus leading to the large-scale immigration of Europeans of the 19th and 20th century, it took Italians several generations to be perceived as entirely “white”, while the Irish and Jews were essentially “white” by the second generation.

Sicilian immigrants were particularly suspect: not only were they more olive-skinned then their northern European counterparts, but the timing of the arrival of the majority of Sicilian immigrants (between 1880-1921, over 4 million Italians entered the U.S.) made their initiation into the racial quagmire of the Reconstruction period in the U.S. much more rocky than other immigrant groups. Although the vast majority of lynchings targeted African Americans, and while Native Americans, Jews, Mexicans and Chinese men were also lynched during this period. The number of Italians and the geographic range of the lynchings are astounding: there are a total of over 50 documented cases of lynchings of Italians in such places as New York, Florida, Mississippi, Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, Chicago, Florida, and Seattle, Washington.

In this powerful, and painful, documentary, M. Heather Hartley illustrates the violent prejudice that many Italian immigrants and Italian Americans faced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The film examines the convergence of social, economic and historical causes of the unspoken history of the lynching of Italians throughout the U.S. during this period. The most dramatic case of lynching occurred in 1891 New Orleans, when 11 Italians were lynched by a mob. This event, which is widely known in Italy even today, is mentioned in a brief paragraph or footnote in most American history texts.

With the use of archival footage, with animation and audio effects added, old photographs, letters, illustrated magazine and newspaper articles, Hartley documents how conditions in Italy played a role leading up to this event: after arriving on Ellis Island, although most settled in New York and other northeastern cities, many southern Italian immigrants found their way to Louisiana where there was plantation work, and where the climate was not unlike that of southern Italy.

Since many Italian men planned to work in the U.S. and return to Italy to marry and raise a family, assimilation, including any desire to learn the culture, language and racist attitudes of their temporary home country, was not a priority: Italians in late 19th century New Orleans worked alongside blacks as laborers, and the various fish and fruit stands that Italian immigrants owned sold food to blacks: white New Orleanians of a certain class responded with hostility. By the 1890s, as many as 30,000 Italians were living and working in New Orleans Stereotypes of Italians as criminals, beggars or organ grinders abounded in Louisiana and throughout the U.S.

When a popular New Orleans police chief was assassinated, the hostility reached its apex and Italians were blamed. There was a massive roundup of Italians after the murder, with nine Italian men eventually tried and acquitted of murder. The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that “[t]he little jail was crowded with Sicilians whose low, receding foreheads, repulsive countenances and slovenly attire proclaimed their brutal nature.” As Hartley notes, a lynching is when a mob of three or more people attack with intent to kill an accused person or group, usually of a specific race or ethnicity, in order to circumvent the legal system or under the assumption that the legal system would not provide affective retaliation. After the trial, city leaders actually advertised that they would be bringing justice to Chief Police Hennessey’s murderers, targeting six of the Italians for lynching (future historians of the period have noted that these six Italians were probably guilty). On the appointed day, prison guards released the six men hoping they would escape and find safety, yet 150 men broke into the jail to search for the Italians. They found a total of 11 Italian men who were shot, beaten to death and/or hung: some of the bodies had 10-40 gunshot wounds.

Hartley notes that while the mob that killed the Italians was never charged (the New York Times had an editorial supporting the lynching as a warning to other Italian “criminals”), the U.S. government sent $25,000 to Italy as restitution, an indemnity paid after almost every other lynching of an Italian in this period. Anti-Italian immigrant sentiment grew after the lynching, with increasingly negative depictions of Italians in the press, including the common association of Italians, particularly Sicilians, with the mafia. Hartley also documents lynchings that occurred after New Orleans, such as the two DeFatta brothers and three other men in 1899 Mississippi, and the lynching of two Italians in Tampa, Florida in 1910. In the latter incident, in one of the only visual pieces of evidence of the violence against Italians, photographers took photos of the two lynched men: Hartley’s camera focuses in on the photographs turned into postcards.

Overall, the film is a dramatic, yet straightforward account, of this little known dark chapter in American history. The narrator’s retelling of the events, accompanied by the mostly still or recreated images, could not be more disturbing had there been film evidence of the events.

Overall, the film is a dramatic, yet straightforward account, of this little known dark chapter in American history. The narrator’s retelling of the events, accompanied by the mostly still or recreated images, could not be more disturbing had there been film evidence of the events.

Stacey Lee Donohue

Central Oregon Community College

***

Dark Legacy

May 1, 2004

Five years ago, while researching the Italian-American experience, filmmaker Heather Hartley stumbled onto one of the uglier episodes in American history: the lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans in March of 1891. Like most Americans, Hartley, assistant professor of communications at Penn State, had never heard of the incident. Intrigued, she resolved to make it the focus of a short film.

As she proceeded, however, Hartley's research turned up another lynching of Italians, then another. "The more I looked, the more I uncovered," she remembers. Accounts told of lynchings in Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, Colorado, Kentucky, Illinois, Washington, and New York between the years of 1885 and 1915, some 50 killings in all.

To Hartley, these incidents seemed clearly of a piece with a sorrowful, and much larger, legacy—one involving mostly African Americans as victims. But this was a part of the story that hadn't been told. Her resolve to correct that situation has resulted in the documentary Linciati: Lynchings of Italians in America.

Archives in New Orleans, Colorado, and Florida helped her piece together evidence from contemporary newspapers and illustrated magazines with government documents and interviews with regional historians. At Tuskegee, where an archive details almost 5,000 recorded instances of lynching in the United States, she learned that a lynching does not necessarily involve hanging. "And it's not the same thing as a hate crime," she says. Rather, lynching is "the use of violence by a mob of three or more to injure or kill a person accused of a crime in order to prevent legal arrest, detention, trial, or punishment." According to Cynthia Wilson, a curator of the Tuskegee archives who appears in the film, the definition turns on "due process of law denied, primarily because of race."

Hartley posits a number of reasons for the targeting of Italians. Economic hardship had caused a souring of attitudes toward the immigrants recruited as cheap labor for mines, railroads, and sugar-cane fields. In many cases, Italians remained apart, choosing not to assimilate as readily as other new groups did. In the South, especially, they also stirred resentment by freely serving African Americans in their businesses and mingling with them as social equals, the film states. All of these factors aggravated existing stereotypes of southern Italians as "beggars, organ grinders, and criminals."

Under such conditions, the potential sparks to violence were many. In Tampa, Florida, in 1910, after a shooting during a labor dispute in the city's fractious cigar industry, two Italians were taken from a jail and hanged. In Tallulah, Louisiana, in 1899, a dispute between neighbors over a goat ended with five Italians dead and two more driven from their homes.

The most egregious example, in New Orleans, was precipitated by a rivalry between two groups of Italian dockworkers. When the city's police chief was shot and killed shortly before he was to testify against one of these groups, Italian males in the city were rounded up indiscriminately. The New Orleans Times-Democrat captured the mood: "The little jail was crowded with Sicilians," the paper reported, "whose low, receding foreheads, repulsive countenances and slovenly attire proclaimed their brutal nature."

Nine Italian men were tried and acquitted of murder. In response, a large mob led by some of the city's leading citizens stormed the parish prison, shot nine men as they cowered in their cells, then dragged out and hanged two more. It was the largest lynching in American history, and although no one was indicted for the crime, President Benjamin Harrison subsequently paid reparations of $25,000 to the Italian government.

Hartley's challenge in recreating such events, she says, was to give them full weight in a film that would yet be bearable to watch. "The lack of photographic documentation actually helped me," she says. "I don't think anyone could sit through a 51 minute film of images of bodies hanging." She had to find other ways to evoke the violence— audio effects, newspaper sketches, and an animation technique she developed to mask archival footage. The narrative is powerfully matched with original music composed by Penn State graduate student Peter Buck.

"People of other groups were lynched, too," Hartley stresses, "especially people of color. That's a point I want people to take away. Italians were victimized, in part, because they weren't considered white." In contemporary newspaper accounts, she notes, the perpetrators of these crimes were typically unrepentant: They were protecting white supremacy; their victims were not human beings, but "vermin," a criminal class.

Why is this history relevant now? Hartley ends her film with that question, and an answer. Where people are placed under suspicion merely because of skin color or nationality; detained without due process of law; or executed without adequate representation, she suggests, elements of lynching may remain.

Heather Hartley, M.F.A., is assistant professor of communications in the School of Communications, 116 Carnegie Building, University Park, PA 16802; 814-865-2176; mhh5@psu.edu. Her film, Linciati: Lynchings of Italians in America, was produced with funding from the College of Communications, the Institute for the Arts and Humanities, Outreach and Cooperative Extension, and the President's Fund for Undergraduate Research.

How can I get the names of the victims in this?

ReplyDeleteThe largest mass lynching in the US occurred in Los Angeles, 1871, against Chinese. http://www.laweekly.com/news/how-los-angeles-covered-up-the-massacre-of-17-chinese-2169478

ReplyDeleteThanks for your correction. Here is Wikipedia's entry on "The Chinese Massacre Of 1871." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_massacre_of_1871

DeleteHere is the link to "The Biggest Mass Lynching In The United States, L.A., 1871 (Correcting My Earlier Error)" http://paxonbothhouses.blogspot.com/2017/04/the-biggest-mass-lynching-in-united.html

ReplyDelete