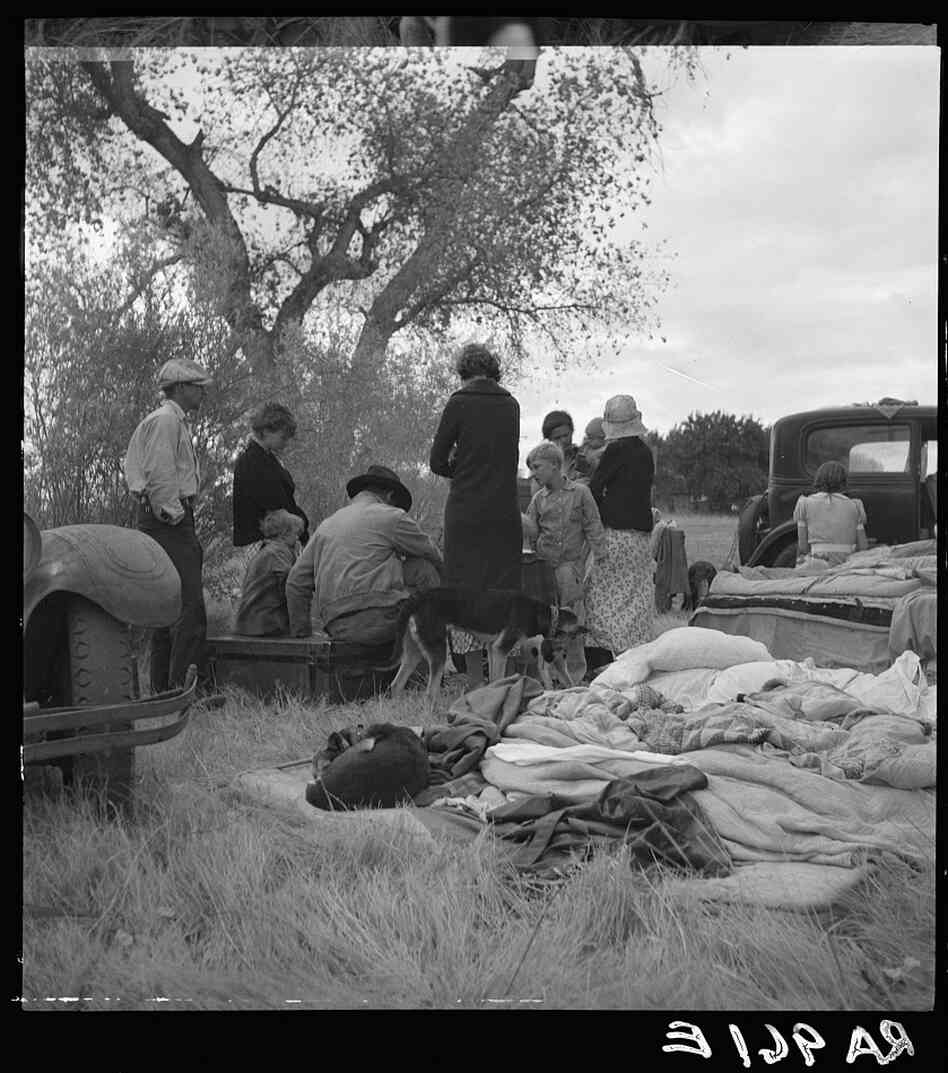

Much has been said and written about the Dust Bowl, but if you want to get a visceral feel for how it all began and the way it affected the people who experienced it, you need go no further than the opening pages of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath:

Steinbeck's novel follows the Joad family as they flee Dust Bowl Oklahoma for a new life in California. When the book was first published — 75 years ago Monday — it was a best-seller. But Susan Shillinglaw, an English professor at San Jose State University and author of the book On Reading The Grapes of Wrath, says it also came under fierce attack.

"Part of the shock, initially, was resistance to believing that there was that kind of poverty in America," she says. "Other people thought that Steinbeck was a communist and they didn't like the book because they thought that that collective action that the book is moving towards – 'cause it really is moving from 'I' to 'we' — was threatening to, sort of, American individualism."

As powerful as the book is in its portrayal of the Dust Bowl era, Shillinglaw says The Grapes of Wrath cannot be contained by its setting. She believes Steinbeck created a timeless myth.

"He saw dispossession as a theme and as a story much larger than, you know, the California stors," she says. "So I think he always knew what he was about in terms of the sort of mythic parallels. Tom Joad's exit from the book, for example — you know, he exits saying, 'I'll be there wherever people are hungry' — so he kind of says: Throughout time, there's going to be a need for me. And that takes the book out of the 1930s."

Tom Joad's final words to his mother have echoed down the years, driven not in small part by Henry Fonda's portrayal of Joad in the 1940 film version of the book.

Last #NPRGrapes Book Club Meeting

"I'll be all aroun' in the dark," Tom says. "I'll be ever'where — wherever you look. Wherever they's a fight so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever they's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there ... I'll be in the way guys yell when they're mad an' — I'll be in the way kids laugh when they're hungry and they know supper's ready. An' when our folks eat the stuff they raise an' live in the houses they build — why, I'll be there."

Last fall, the California-based National Steinbeck Center sent three artists on the road to retrace the journey that the Joads took from Oklahoma. One of them was filmmaker P.J. Palmer.

"Every type of weather you can think of we experienced in those 10 days," Palmer says. "It's not a comfy ride, and so I don't understand how they pulled in off in the 1930s. It must have been really, really crazy."

Palmer is finishing a documentary on the trip.

Retrace The Joads' Journey:

"We really wanted to come out and sort of take the temperature of the country again," he says. "Steinbeck did it back in '30s and we decided to take that trip to sort of see what things are like now."

Much has changed over the decades. The land has been restored; they didn't see any destitute families on the side on the road; but they still came across many people struggling to survive — poverty and homelessness persist.

"We met a lot of people out of work," Palmer says. "We met people who were kind of going through their own personal Dust Bowls. If it wasn't that they were unemployed or in an environmental disaster, they still had their own personal traumas and tragedies that they were working through."

Palmer interviewed some of the people they met along the way: a single dad caring for his son with cancer; a woman who lost both parents as child and was trying to start life again after leaving prison; migrant workers who now live in the same camps the Joads found in California.

So it's no surprise that many can still identify with The Grapes of Wrath.

"People read their own stories into it because it's really about poverty," Susan Shillinglaw says. "It's about haves and have-nots, and that story is getting increasingly urgent ... This is a story about people losing ground with every step of the way along Route 66 — that's a story that seems, like, really very contemporary."

More On 'Grapes Of Wrath'

Filmmaker P.J. Palmer says the book is also a story of survival and resilience; a powerful plea for people to work together with a sense of shared responsibility for those who have fallen on hard times.

"The scary part is that much of what happened we're forgetting," he says. "There's a reason why the New Deal happened. You know, I do understand that the country had gone through an enormous environmental disaster. It had gone through a major Depression. Hopefully we won't have to go through that again, but we still have these huge problems with people unable to work or find a job, and people who don't have a home, and we're sort of still stripping things back politically ... And I kind of feel like: Did you guys read the book? Did you see the movie? Do you remember what happened?"

Seventy-five years later, The Grapes of Wrath still isn't universally loved — it remains one of the most frequently banned books in this country. But it's also a powerful reminder of a past that no one really wants to see repeated.

No comments:

Post a Comment