Views of violence in Judaism

From Wikipedia, the

free encyclopedia

The love of peace and the pursuit of peace, as well as laws requiring the

eradication of "evil" using violent means, co-exist within the Jewish

tradition.[1][2][3][4] Laws

requiring the eradication of evil, sometimes using violent means, exist in the

Jewish tradition alongside doctrines rejecting violence.[1][5] This

article deals with the juxtaposition of Judaic law and theology to violence and

non-violence by groups and individuals. Attitudes and laws towards both peace

and violence exist within the Jewish tradition.[1] Throughout

history, Judaism's

religious texts or precepts have been used to promote[6][7][8] as

well as oppose violence.[9]

|

Rejection of Violence and

Pursuit of Peace

Main article: Judaism

and peace

Judaism's religious texts endorse compassion and peace, and the Hebrew

Bible contains the well-known commandment to "love thy neighbor as

thyself".[5] In

fact, the love of peace and the pursuit of peace is one of the key principles

in Jewish law. Jewish tradition permits waging war and killing in certain

cases, however, the requirement is that one always seek a just peace before

waging war.[1]

According to the 1947 Columbus

Platform of Reform

Judaism, "Judaism, from the days of the prophets, has

proclaimed to mankind the ideal of universal peace, striving for spiritual and

physical disarmament of all nations. Judaism rejects violence and relies upon

moral education, love and sympathy."[9]

The philosophy of Nonviolence has

roots in Judaism, going back to the Jerusalem

Talmud of the middle 3rd century. While absolute nonviolence is

not a requirement of Judaism, the religion so sharply restricts the use of

violence, that nonviolence often becomes the only way to fulfilling a life of

truth, justice and peace, which Judaism considers to be the three tools for the

preservation of the world.[10]

Jewish law (past and present) does not permit any use of violence unless it

is in self-defense.[11] Any

person that even raises his hand in order to hit a nother person is called

"evil.".[12]

Guidelines from the Torah to the 'Jewish Way to Fight a War': When the time

for war has arrived, Jewish soldiers are expected to abide by specific laws and

values when fighting. Jewish war ethics attempts to balance the value of

maintaining human life with the necessity of fighting a war. Judaism is

somewhat unique in that it demands adherence to Jewish values even while

fighting a war. The Torah provides the following rules for how to fight a war.

Pursue Peace Before Waging War. Preserve the Ecological Needs of the

Environment. Maintain Sensitivity to Human Life. The Goal is Peace[13]

The ancient commands (like those) of wars for the Israelites to eradicate

idol worshipping do not apply in Judaism today. Jews are not taught to glorify

violence. The rabbis of the Talmud saw war as an avoidable evil. They taught,

'The sword comes to the world because of delay of justice and through

perversion of justice.' Jews have always hated war and Shalom expresses the

hope for peace; in Judaism war is an evil, but at times a necessary one, yet,

Judaism teaches that one has to go to great length to avoid it.[14]

Claims that Judaism is violent

Claims that monotheistic religions are inherently violent

Some critics of religion such as Jack Nelson-Pallmeyer argue that all

monotheistic religions are inherently violent. For example, Nelson-Pallmeyer writes

that "Judaism, Christianity and Islam will continue to contribute to the

destruction of the world until and unless each challenges violence in

"sacred texts" and until each affirms nonviolent power of God".[15]

Bruce Feiler writes that "Jews and Christians who smugly console

themselves that Islam is the only violent religion are willfully ignoring their

past. Nowhere is the struggle between faith and violence described more

vividly, and with more stomach-turning details of ruthlessness, than in the

Hebrew Bible".[16] Similarly,

Burggraeve and Vervenne describe the Old Testament as full of violence and

evidence of both a violent society and a violent god. They write that,

"(i)n numerous Old Testament texts the power and glory of Israel's God is

described in the language of violence." They assert that more than one

thousand passages refer to YHWH as acting violently or supporting the violence

of humans and that more than one hundred passages involve divine commands to

kill humans.[17]

Claims that Judaism is a violent religion

Some Christian churches and theologians argue that Judaism is a violent

religion and the god of Israel as a violent god. Reuven Firestone asserts that

these assertions are usually made in the context of claims that Christianity is

a religion of peace and that the god of Christianity is one that expresses only

love.[18]

Principle of minimization of violence

Normative Judaism is not pacifist and violence is condoned in the service

of self-defense.[19] J.

Patout Burns asserts that Jewish tradition clearly posits the principle of

minimization of violence. This principle can be stated as "(wherever)

Jewish law allows violence to keep an evil from occurring, it mandates that the

minimal amount of violence be used to accomplish one's goal."[20]

Warfare

Main article: Judaism

and war

Regarding war, the commandment of Milkhemet

Mitzvah (Hebrew: מלחמת מצווה, "War by commandment")

refers to a war during the times of the Bible when a king would go to war in

order to fulfill something based on, and required by, the Torah.[21]

What is a milchemet mitzvah? It is a war to assist Israel against an enemy

that has attacked them.

-Maimonedies, Laws of Kings 5:1

Wars of this type do not need the approval of the Sanhedrin.[citation needed]

This is in contrast to a Milkhemet Reshut (a discretionary war), which

according to Jewish law require the permission of a Sanhedrin.[citation needed] These

wars (discretionary wars) tend to be for economic reasons and had exemption

clauses (Deuteronomy 20:5) while, milhemet mitzvah tended to be invoked in

defensive wars, when vital interests were at risk and had no such exemption

clauses.[22]

The Talmud insists that before going to non-defensive war, the king would

need to seek authorization from the Sanhedrin,

as well as divine approval through the High Priest. As these institutions have

not existed for 2,000 years, this virtually rules out the possibility of

non-defensive war.[23]

The permissibility of war is limited and the requirement is that one always

seek a just peace before waging war.[1][24] Modern

Jewish scholars hold that the calls to war these texts provide no longer apply,

and that Jewish theology instructs Jews to leave vengeance to God.[25] [26]

Laws of siege

According to Deuteronomy,

an offer of peace is to be made to any city which is besieged, conditional on

the acceptance of terms of tribute.[23] According

to Maimonides,

on besieging a city in order to seize it, it must not be surrounded on all four

sides but only on three sides, thus leaving a path of escape for whomever

wishes to flee to save his life.[27] Nachmanides,

writing a century later, strengthened the rule and added a reason: "We are

to learn to deal kindly with our enemy." [27]

Forbidden war tactics

Jewish law prohibits the use of outright vandalism in warfare.[28] It

forbids destruction of fruit trees as a tactic of war. It is also forbidden to

break vessels, tear clothing, wreck that which is built up, stop fountains, or

waste food in a destructive manner. Killing an animal needlessly or offering poisoned

water to livestock are also forbidden.[28] According

to Rabbi Judah

Loew of Prague, Jewish law forbids the killing of innocent

people, even in the course of a legitimate military engagement.[27]

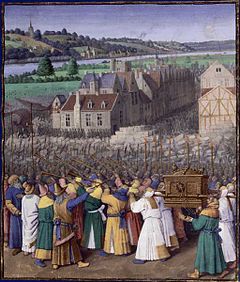

Wars of extermination in the Tanakh

See also: Herem

(war or property)

The Tanakh (Jewish

Bible) contains commandments that

require the Israelites to exterminate seven Canaanite nations, and describes

several wars of extermination that annihilated entire cities or groups of

peoples.

Wars of extermination are of historical interest only, and do not serve as

a model within Judaism.[23] A

formal declaration that the “seven nations” are no longer identifiable was made

by Joshua

ben Hananiah, around the year 100 CE.[23]

Extermination is described in several of Judaism's biblical commandments,

known as the 613

Mitzvot:[29]

- Not to keep alive any individual of the seven

Canaanite nations (Deut. 20:16)

- To exterminate the seven Canaanite nations from the

land of Israel (Deut. 20:17)

- Always to remember what Amalek did (Deut. 25:17)

- That the evil done to us by Amalek shall not be forgotten

(Deut. 25:19)

- To destroy the seed of Amalek (Deut. 25:19)

The extent of extermination is described in the commandment Deut 20:16-18 which

orders the Israelites to "not leave alive anything that breathes…

completely destroy them …".[30] Several

scholars have characterized the exterminations as genocide.[31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40]

Victims

The targets of the extermination commandments were the seven Canaanite

nations explicitly identified by God as targets in Deut 7:1-2 and Deut 20:16-18.[41] These

seven tribes are Hittites, Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites,Perizzites, Hivites,

and Jebusites.

Most of these descended from the biblical figure Canaan,

as described in Gen 10:15-18. In addition, two

others tribes were subject to wars of extermination: Amalekites (1 Samuel 15:1-20)[42] andMidianites (Numbers 31:1-18). The

extermination of the Canaanite nations is described primarily in the Book

of Joshua (especially Joshua 10:28-42) which

includes the Battle

of Jericho described in Joshua 6:15-21.

The instruction God gives in Deut 20:16-18 is for

Israelites to exterminate "everything that breathes", but the precise

extent of the killing varied:[43] The

instruction was made with respect to the Amalekites 1 Samuel 15:1-20,

Canaanites (Battle

of Jericho) Joshua 6:15-21, Canaanite

nations Joshua 10:28-42, and

Midianites Numbers 31:1-18.[41]

Some scholars such as Van Wees conclude that the biblical accounts of

extermination are exaggerated, fictional, or metaphorical.[44] In

the archaeological community, the Battle

of Jericho is very thoroughly studied, and the consensus of

modern scholars is that the story of battle and the associated extermination

are a pious

fiction and did not happen as described in the Book of Joshua.[45] For

example, the Book

of Joshua describes the extermination of the Canaanite tribes,

yet at a later time, Judges 1:1-2:5 suggests

that the extermination was not complete.[46]

Likewise, it is not clear if the historical Amalekites were exterminated or

not. 1 Samuel 15:7-8 implies ("He took Agag king of the Amalekites alive,

and all his people he totally destroyed with the sword.") that - after

Agag was also killed - the Amalekites were extinct, but in a later story in the

time of Hezekiah, the Simeonites annihilated some Amalekites on Mount Seir, and

settled in their place: "And five hundred of these Simeonites, led by

Pelatiah, Neariah, Rephaiah and Uzziel, the sons of Ishi, invaded the hill

country of Seir. They killed the remaining Amalekites who had escaped, and they

have lived there to this day." (1 Chr 4:42-43).[citation needed]

As genocide

See also: Genocides

in history

The wars of extermination have been characterized as genocide by

a number of scholars and commentators.[41][47][48] Shaul

Magid characterizes the commandment to exterminate the Midianites as a

"genocidal edict", and asserts that rabbinical tradition continues to

defend the edict into the 20th century.[49] L.

Daniel Hawk describes the extermination of Canaanites as "ethnic

cleansing", but notes that the narrative includes contradictory indications

that Canaanites were absorbed into Israeli society.[50][51] Ra'anan

Boustan, Alex Jassen, and Calvin Roetzel assert that - in the modern era - the

violence directed towards the Canaanites would be characterized as genocide.[52] Zev

Garber characterizes the commandment to wage war on the Amalekites as genocide.[53] Pekka

Pitkanen asserts that Deuteronomy involves "demonization of the opponent"

which is typical of genocide, and he asserts that the genocide of the

Canaanites was due to unique circumstances, and that "the biblical

material should not be read as giving license for repeating it."[54]

Explanations

Several explanations for the extreme violence associated with the wars of

extermination have been offered, some found in the Jewish

Bible, others provided by Rabbinic commentators, and others

hypothesized by scholars.

In Deut 20:16-18 God tells

the Israelites to exterminate the Canaanite nations, "otherwise, they will

teach you to follow all the detestable things they do in worshiping their gods,

and you will sin against the lord your God". Another reason was revenge

for Midian's role in Israel's apostate behavior during the Heresy

of Peor (Numbers 25:1-18).[55]

Another justification is that the Canaanites were sinful, depraved people,

and their deaths were punishments (Deut 9:5). Another

justification for the exterminations is to make room for the returning

Israelites, who are entitled to exclusive occupation of the land of Canaan: the

Canaanite nations were living in the land of Israel, but when the Israelites

returned, the Canaanites were expected to leave the land.[56]

In Talmudic commentary, the Canaanite nations were given the opportunity to

leave, and their refusal to leave "lay the onus of blame for the conquest

and Joshua's extirpation of the Canaanites at the feet of the victims."[57] Another

explanation of the exterminations is that God gave the land to the Canaanites

only temporarily, until the Israelites would arrive, and the Canaanites

extermination was punishment for their refusal to obey God's desire that they

leave.[58] Another

Talmudic explanation - for the wars in the Book

of Joshua - was that God initiated the wars as a diversionary

tactic so Israelites would not kill Joshua after discovering that Joshua had

forgotten certain laws.[59]

Some scholars trace the extermination of the Midianites to revenge for the

fact that Midianites were responsible for selling Joseph into

slavery in Egypt (Genesis 37:28-36).[60]

Association with violent attitudes in the modern era

Some analysts have associated the biblical commandments of extermination

with violent attitudes in modern era.

According to Ian

Lustick, leaders of the now defunct[61] Jewish

fundamentalist movement Gush

Emunim, such as Hanan

Porat, consider the Palestinians to be like Canaanites or

Amalekites, and suggest that infers a duty to make merciless war against Arabs

who reject Jewish sovereignty.[62] Atheist

commentator Christopher

Hitchens discusses the association of the

"obliterated" tribes with modern troubles in Palestine.[63]

Niels

Peter Lemche asserts that European colonialism in the 19th

century was ideologically based on the biblical narratives of conquest and

extermination. He also states that European Jews who migrated to Palestine

relied on the biblical ideology of conquest and extermination, and considered

the Arabs to be Canaanites.[64] Scholar

Arthur Grenke claims that the view of war expressed in Deuteronomy contributed

to the destruction of Native Americans and to the destruction of European Jewry.[65]

Nur

Masalha writes that the "genocide" of the

extermination commandments has been "kept before subsequent generations"

and served as inspirational examples of divine support for slaughtering enemies.[66] Ra'anan

Boustan, Alex Jassen, and Calvin Roetzel assert that, like other groups have

done to their enemies, militant Zionists have identified modern Palestinians

with Canaanites, and hence as targets of violence mandated in Deut 20:15-18.[67] Scholar

Leonard B. Glick states that Jewish fundamentalists in Israel, such as Shlomo

Aviner, consider the Palestinians to be like biblical Canaanites,

and that some fundamentalist leaders suggest that they "must be prepared

to destroy" the Palestinians if the Palestinians do not leave the land.[68] Scholar

Keith Whitelam asserts that the Zionist movement has drawn inspiration from the

biblical conquest tradition, and Whitelam draws parallels between the

"genocidal Israelites" of Joshua and modern Zionists.[69]

Commandment to exterminate the Amalekites

See also: Amalekites

The Jewish Bible contains a mitzvah (commandment)

to exterminate the Amalekites, based on the verse 1 Samuel 15 "Now, go and

crush Amalek; put him under the curse of destruction with all that he

possesses. Do not spare him, but kill man and woman, babe and suckling, ox and

sheep, camel and donkey." Some commentators, including Maimonides,

have discussed the ethics of the commandment to exterminate all the Amalekites,

including the command to kill all the women and children, and the notion of

collective punishment.[70] Maimonides

explains that the commandment of killing out the nation of Amalek requires the

Jewish people to peacefully request of them to accept upon themselves the Noachide

laws and pay a tax to the Jewish kingdom. Only if they refuse

is the commandment applicable. Some commentators, such as Rabbi Hayim

Palaggi (1788–1869) argued that Jews had lost the tradition of

distinguishing Amalekites from other people, and therefore the commandment of

killing them could not practically be applied.[71] Rabbis

nullified the Torah’s commands to kill idolatrous people, by ruling that the

Canaanite peoples no longer existed, that the Assyrians, not Israelites, had

wiped them out – and therefore the command was a dead letter.[72] In

addition, the Talmud asserts

that today "since Sancheriv mixed up the nations, there is no nation that

is identified as Amalek."[73]

In later Jewish tradition,

the Amalekites came to represent the metaphorical enemy of the Jews. Nur

Masalha, Elliot Horowitz and Josef Stern suggest that Amalekites

have come to represent an "eternally irreconcilable enemy" that wants

to murder Jews, and that Jews In post-biblical times sometimes associate

contemporary enemies with Haman or Amalekites, and that some Jews believe that

pre-emptive violence is acceptable against such enemies.[74] Nur

Masalha and other scholars describe several associations of

modern Palestinians with

Amalekites, including recommendations by rabbi Israel

Hess to kill Palestinians, which are based on biblical verses

such as 1 Samuel 15.[75]

Modern warfare

The permissibility to wage war is limited and the requirement is that one

always seek a just peace before waging war.[1]

Some commentators claim that religious leaders have interpreted Jewish

religious laws to support killing of innocent civilians during wartime in some

circumstances, and that this interpretation was asserted several times: in 1974

following the Yom

Kippur war, [76] in

2004, during conflicts in West

Bank and Gaza,[77] and

in the 2006

Lebanon War.[78] However,

major and mainstream religious leaders have condemned this interpretation, and

the Israeli military subscribes to the Purity

of arms doctrine, which seeks to minimize injuries to

non-combatants; furthermore, the advice was only applicable to combat

operations in wartime.

Activist Noam

Chomsky claims that leaders of Judaism in Israel play a role in

sanctioning military operations: "[Israel's Supreme Rabbinical Council]

gave their endorsement to the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, declaring that it

conformed to the Halachi (religious) law and that participation in the war 'in

all its aspects' is a religious duty. The military Rabbinate meanwhile

distributed a document to soldiers containing a map of Lebanon with the names

of cities replaced by alleged Hebrew names taken from the Bible.... A military

Rabbi in Lebanon explained the biblical sources that justify 'our being here

and our opening the war; we do our Jewish religious duty by being here.'"[79]

In 2007, Mordechai

Eliyahu, the former Sephardi Chief

Rabbi of Israel wrote that "there was absolutely no moral

prohibition against the indiscriminate killing of civilians during a potential

massive military offensive on Gaza aimed at stopping the rocket

launchings".[80] His

son, Shmuel

Eliyahu chief rabbi of Safed,

called for the "carpet bombing" of the general area from which the

Kassams were launched, to stop rocket attacks on Israel, saying "This is a

message to all leaders of the Jewish people not to be compassionate with those

who shoot [rockets] at civilians in their houses." he continued, "If

they don't stop after we kill 100, then we must kill 1,000. And if they don't

stop after 1,000, then we must kill 10,000. If they still don't stop we must

kill 100,000. Even a million. Whatever it takes to make them stop."[80] In

March 2009, he called for "state-sponsored revenge" to restore

"Israel's deterrence... It's time to call the child by its name: revenge,

revenge, revenge. We mustn't forget. We have to take horrible revenge for the terrorist

attack at Mercaz Harav yeshiva," referring to an earlier

incident in which eight students were brutally gunned down in cold blood.

"I am not talking about individual people in particular. I'm talking about

the state. (It) has to pain them where they scream 'Enough,' to the point where

they fall flat on their face and scream 'help!' "[81]

An influential Chabad Lubavitch Hassid rabbi Manis

Friedman in 2009 was quoted as saying: "I don’t believe in

western morality, i.e. don’t kill civilians or children, don’t destroy holy

sites, don’t fight during holiday seasons, don’t bomb cemeteries, don’t shoot

until they shoot first because it is immoral. The only way to fight a moral war

is the Jewish way: Destroy their holy sites. Kill men, women and children".[82] Later,

Friedman explained: "the sub-question I chose to address instead is: how

should we act in time of war, when our neighbors attack us, using their women,

children and religious holy places as shields."[83]

Retribution and punishment

Eye for an eye

Main article: Eye

for an eye

George Robinson characterizes the passage of Exodus that contains the

principle of lex talionis ("an

eye for an eye") as one of the "most controversial in the

Bible." According to Robinson, some have pointed to this passage as

evidence of the vengeful nature of justice in the Hebrew Bible.[84] Similarly,

Abraham Bloch asserts that the "lex talionis has been singled out as a

classical example of biblical harshness."[85]

Harry S. Lewis points to Lamech, Gideon and Samson as Biblical heroes who

were renowned for "their prowess in executing blood revenge upon their

public and private enemies. Lewis asserts that this "right of 'wild'

justice was gradually limited."[86] Isaac

Kalimi explains that the “lex talionis was humanized by the Rabbis who

interpreted it to mean pecuniary compensation. As in the case of the lex

talionis, humanization of the law replaces the peshat of

the written Torah law.[87] Pasachoff

and Littman point to the reinterpretation of the lex talionis as an example of

the ability of Pharisaic Judaism to "adapt to changing social and

intellectual ideas."[88] Stephen

Wylen asserts that the lex talionis is "proof of the unique value of each

individual" and that it teaches "equality of all human beings for

law."[89]

Capital and corporal punishment

Main article: Capital

and corporal punishment (Judaism)

The Jewish

Bible specifies several violent punishments, including death by

stoning, decapitation, and burning. Judaism's oral law, the Talmud,

additionally includes the punishment of death by strangulation for some crimes.[90] Violent

punishments by death are referred to in several of Judaism's 613

mitzvot.[91] The

transgressions that call for violent punishment by death in Judaism include the

following: cursing one's parents,[92] fornication

(sex outside of marriage),[93]bestiality,[94] sorcery,[95] taking

advantage of widows or orphans,[96] blasphemy,[97] stubborn

and rebellious son,[98] incest,[99] adultery,[100] and

homosexuality.[101] Whipping

is specified as punishment for lesser transgressions.[102]

The punishments established in the biblical era were substantially modified

during the rabbinic era, primarily by adding additional requirements for

conviction. As a consequence, the death penalty was very rarely applied, and it

became more of a principle than a practice. The Talmud states that a court that

executes one person in seven years is considered bloodthirsty (Makkot 1:10).

The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar Maimonides stated

that "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty

persons than to put a single innocent one to death."[103]

Purim and the Book of Esther

The Book

of Esther, one of the books of the Jewish Bible, is a story of

palace intrigue centered on a plot to kill all Jews which was thwarted by Esther,

a Jewish queen of Persia. Instead of being victims, the Jews killed "all

the people who wanted to kill them."[104] The

king gave the Jews the ability to defend themselves against their enemies who

tried to kill them.[105] numbering

75,000 (Esther 9:16) including Haman,

an Amalekite that

led the plot to kill the Jews. The annual Purim festival

celebrates this event, and includes the recitation of the biblical instruction

to "blot out the remembrance [or name] of Amalek". Scholars -

including Ian

Lustick, Marc

Gopin, and Steven

Bayme - state that the violence described in the Book

of Esther has inspired and incited violent acts and violent

attitudes in the post-biblical era, continuing into modern times, often

centered on the festival of Purim.[106]

Other scholars, including Jerome Auerbach, state that evidence for Jewish

violence on Purim through the centuries is "exceedingly meager",

including occasional episodes of stone throwing, the spilling of rancid oil on

a Jewish convert, and a total of three recorded Purim deaths inflicted by Jews

in a span of more than 1,000 years.[107] In

a review of historian Elliot Horowitz's book Reckless rites: Purim and

the legacy of Jewish violence , Hillel

Halkin pointed out that the incidences of Jewish violence

against non-Jews through the centuries are extraordinarily few in number and

that the connection between them and Purim is tenuous.[108]

Rabbi Arthur

Waskow and historian Elliot Horowitz state that Baruch

Goldstein, perpetrator of the Cave

of the Patriarchs massacre, may have been motivated by the Book of

Esther, because the massacre was carried out on the day of Purim[109] but

other scholars point out that the association with Purim is circumstantial

because Goldstein never explicitly made such a connection.[110]

The festival has been used by non-Jews as an opportunity to direct violence

against Jews. Nazi

attacks against Jews often coincided with Jewish festivals and

on Purim 1942, ten Jews were hanged in Zduńska

Wola to avenge the hanging of Haman's ten sons.[111] In

a similar incident in 1943, the Nazis shot 10 Jews from the Piotrków ghetto.[112] On

Purim eve that same year, over 100 Jewish doctors and their families were shot

by the Nazis in Czestochowa.

The following day, Jewish doctors were taken from Radom and

shot nearby in Szydlowiec.[112]

Modern

violence

Radical Zionists

The motives for violence by extremist Jewish settlers in the West

Bank directed at Palestinians are complex and varied. Religious

motivations have also been documented.[113][114][115] Some

Jewish religious figures living in the occupied territories have condemned such

behaviour.[116] After Baruch

Goldstein carried out the Cave

of the Patriarchs massacre in 1994, some claimed[who?] that

his actions were influenced by Jewish religious doctrine, based on the ideology

of the Kach movement.[117] The

act was denounced by mainstream Orthodox Judaism.[118]

Ian

Lustick, Benny

Morris, and Nur

Masalha assert that Zionist leaders relied on religious

doctrines for justification for the violent treatment of Arabs in Palestine,

citing examples where pre-state Jewish militia used verses from the Bible to

justify their violent acts, which included expulsions and massacres such as the

one at Deir

Yassin.[119] Jewish

religious leaders at the time condemned such acts.[120]

Abraham

Isaac Kook (1865–1935), the Ashkenazi Chief

Rabbi of Mandate

Palestine, urged that Jewish settlement of the land should proceed

by peaceful means only.[23] Contemporary

settler movements, follow Kook’s son Tzvi

Yehuda Kook (1891–1982), who also did not advocate aggressive

conquest.[23] Critics

claim that Gush

Emunim and followers of Tzvi Yehuda Kook advocate violence

based on Judaism's religious precepts.[121]

Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin

The assassination

of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak

Rabin by Yigal

Amir was motivated by Amir’s personal political views and his

understanding of Judaism's religious law of moiser (the duty

to eliminate a Jew who intends to turn another Jew in to non-Jewish

authorities, thus putting a Jew's life in danger[122])

and rodef (a

bystander can kill a one who is pursuing another to murder him or her if he

cannot otherwise be stopped).[123] Amir’s

interpretation has been described as "a gross distortion of Jewish law and

tradition"[124] and

the mainstream Jewish view is that Rabin's assassin had no Halachic basis to

shoot Prime Minister Rabin.[11]

Extremist organizations

See also: Jewish

religious terrorism

In the course of history there have been some organizations and individuals

that endorsed or advocated violence based on their interpretation to Jewish

religious principles. Such instances of violence are considered by mainstream

Judaism to be extremist aberrations, and not representative of the tenets of

Judaism.[25][26]

- Kach (defunct)

and Kahane

Chai [125][126][127]

- Gush

Emunim Underground (defunct): formed by members of Gush

Emunim.[128]

- Brit

HaKanaim (defunct): an organisation operating in Israel from 1950

to 1953 with the objective of imposing Jewish religious law in the country

and establishing a Halakhic

state.[129]

- The Jewish

Defense League (JDL): founded in 1969 by Rabbi Meir

Kahane in New

York City, with the declared purpose of protecting Jews from

harassment and antisemitism.[130] FBI statistics

show that, from 1980 to 1985, 15 terrorist attacks were attempted in the

U.S. by members of the JDL.[131] The

FBI’s Mary Doran described the JDL in 2004 Congressional testimony as

"a proscribed terrorist group".[132] The National

Consortium for the Study of Terror and Responses to Terrorism states

that, during the JDL's first two decades of activity, it was an

"active terrorist organization.".[130][133] Kahanist groups

are banned in Israel.[134][135][136]

Endorsement of violence by extremist settler rabbis

Some settler rabbis, in the unique conditions of West Bank settlements,[citation needed] issued

statements that diverge from normative Jewish practice.[137]

Dov

Lior, Chief

Rabbi of Hebron and Kiryat

Arba in the southern West

Bank and head of the "Council of Rabbis of Judea

and Samaria" has made speeches legitimizing the killing of

non-Jews and praising Baruch

Goldstein, a Jewish settler who in a deadly

terrorist attack killed 29 Muslim worshippers

while they were praying in mosque in Hebron,

as a saint and martyr. Lior also said "a thousand non-Jewish lives are not

worth a Jew's fingernail".[138][139][140] Lior

publicly gave permission to spill blood of Arab persons and has publicly

supported extreme right-wing Jewish

terrorists.[141]

In July 2010, Yitzhak

Shapira who heads Dorshei Yihudcha yeshiva in

the West

Bank settlement of Yitzhar,

was arrested by Israeli police for writing a book that allegedly encourages the

killing of non-Jews.

In his book "The King's Torah" (Torat Hamelech) he wrote that

under Torah and Jewish

Law it is legal to kill Gentiles.[142] The

section entitled "Conclusions – Chapter Five: The Killing of Gentiles in

War" reads that in some cases it is permitted to kill the babies of enemy

forces "because of the future danger they may present since they will grow

up to be evil like their parents."[143] Later

in August 2010 police arrested rabbi Yosef Elitzur-Hershkowitz - co-author of

Shapira's book - on the grounds of incitement to racial violence, possession of

a racist text, and possession of material that incites to violence. The

controversial book was endorsed by Rabbi Dov

Lior of Kiryat

Arba, a respected figure among many mainstream religious Zionists[137] and Yaakov

Yosef, son of Shas spiritual

leader Ovadia Yosef.[144]

According to Avinoam

Rosenak, "The King's Torah" reflects a fringe viewpoint

held by a minority of rabbis in the West

Bank. The book's wide dissemination and the enthusiastic

endorsements of prominent rabbis have spotlighted what might have otherwise

remained an "isolated commentary". A coalition of religious Zionist

groups, has asked Israel's Supreme Court to order confiscation of books

inciting to violence and to arrest the authors.[137]

Rabbi Zalman Nechemia Goldberg who initially endorsed the book, rescinded

his approval a month after its release, saying that the book includes

statements that "have no place in human intelligence."[137]

The book has also been denounced by Shlomo

Aviner, chief rabbi of Beit

El and head of Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim.[137]

Notable incidents

On 3 October 2010, a mosque in Yasuf village was arsoned, suspected to be

by Jewish extremist settlers.[145][146][147] Chief

Ashkenazi Rabbi Yona

Metzger condemned the attack and equating the arson to Kristallnacht,

he said: "This is how the Holocaust began, the tragedy of the Jewish

people of Europe."[148] Rabbi Menachem

Froman, a well-known peace activist, visited the mosque and replaced

the burnt Koran with new copies.[149] The

rabbi stated: "This visit is to say that although there are people who

oppose peace, he who opposes peace is opposed to God" and "Jewish law

also prohibits damaging a holy place." He also remarked that arson in a

mosque is an attempt to sow hatred between Jews and Arabs.[148][150]

See

also

- Religious

violence

- Christianity

and violence

- Islam

and violence

- Buddhism

and violence

- Mormonism

and violence

- Jewish

religious terrorism

- Jewish

ethics

- Zionist

political violence

- Judaism

and peace

- Persecution of Jews

***

This

Wikipedia entry, "Views of Violence in Judaism," is accompanied by 150 footnotes comprising more than half the

article's overall length. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Views_of_violence_in_Judaism

***

A few years ago I heard Dom Crossan speak at Chautauqua Institution. He did me

the great favor of clarifying a biblical conundrum that most cradle Christians ignore: The Bible presents us with both a

peaceful God and a violent God. The task of believers is to decide which

one to follow.

No comments:

Post a Comment