Raymond Chandler on Writing

"The test of a writer is whether you want to read him again years after he should by the rules be dated."

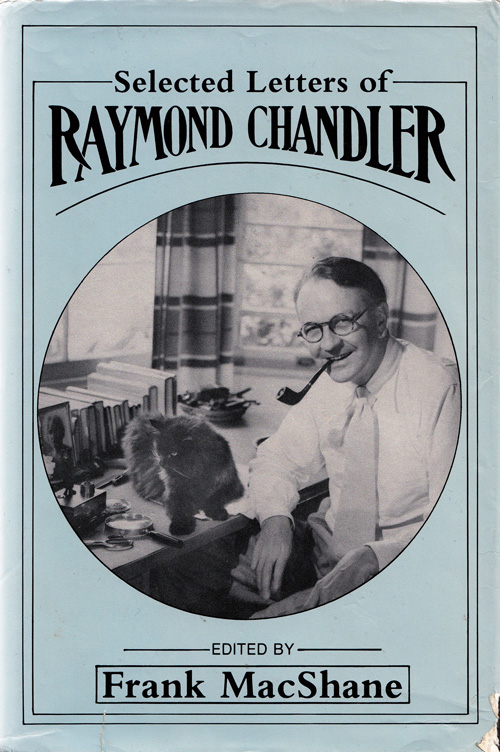

Last week, while researching this omnibus ofwhat famous authors wrote about their beloved pets in their letters and journals, I came upon the irresistible 1981 anthologySelected Letters of Raymond Chandler(public library). Among Chandler's many musings, exchanged with his agents, publishers, and literary friends are a number of timeless insights on writing, culled here as a fine addition to this master-list of famous writers' advice on writing.

Last week, while researching this omnibus ofwhat famous authors wrote about their beloved pets in their letters and journals, I came upon the irresistible 1981 anthologySelected Letters of Raymond Chandler(public library). Among Chandler's many musings, exchanged with his agents, publishers, and literary friends are a number of timeless insights on writing, culled here as a fine addition to this master-list of famous writers' advice on writing.

In a 1937 letter to the editor of The Fortnightly Intruder, Chandler echoes Virginia Woolf's case for the evolution of language:

That you should have pride in your purer American heritage of language seems to me a slight thing. Latin became corrupt, but French is a sharper language than Latin ever was. The best writing in English today is done by Americans, but not in any purist tradition. They have roughed the language around as Shakespeare did and done it the violence of melodrama and the press box. They have knocked over tombs and sneered at the dead. Which is as it should be. There are too many dead men and there is too much talk about them.

In a vital meditation on defining one's own success, Chandler admonishes against pursuing prestige rather than authenticity, which for him is a serious creative block:

I can't seem to get started on doing anything. Always very tough for me to get started. The more things people say about you the more you feel as if you were writing in an examination room, that it didn't belong to you any more, that you had to protect critical reputations and not let them down. Writers even as cynical as I have to fight the impulse to live up to someone else's idea of what they are.

In a 1951 letter to his agent, Carl Brandt, Chandler once again shares his creative block but, like Rilke, welcomes the state of creative doubt and uncertainty, which Keats famously called "negative capability":

I am having a hard time with the book. Have enough paper written to make it complete, but must do all over again. I just didn't know where I was going and when I got there I saw that I had come to the wrong place. that's the hell of being the kind of writer who cannot plan anything, but has to make it up as he goes along and then try to make sense out of it. If you gave me the best plot in the world all worked out I could not write it. It would be dead for me.

In March of 1957, at the age of 69 and critically acclaimed, Chandler revisits this state of creative restlessness and uncertainty as a pillar of his identity as a writer:

I am the same man I was when I was a struggling nobody. I feel the same. I know more, it is true, break all the rules and get away with it, but that doesn't make me important. I may have written the most beautiful American vernacular that has ever been written (some people think I have), but if it is so, I am still a writer trying to find his way through a maze. Should I be anything else? I can't see it.

In the closing lines of a letter dated May 5, 1939, Chandler offers a meta-observation full of that typical writerly self-awareness bordering on self-consciousness:

And here I am at 2:30 A.M. writing about technique, in spite of a strong conviction that the moment a man begins to talk about technique, that's proof he is fresh out of ideas.

On October 17, 1939, he comments on the ever-elusive alignment of lucrative and fulfilling work, the disconnect between authentic work and popular taste:

I have never made any money on writing. I work too slowly, throw away too much, and what I write that sells is not at all the sort of thing I really want to write.

In another letter to fellow detective novelist Earle Stanley Gardner, dated January 29, 1946, Chandler dives even deeper into his distaste for such writing and shares in Susan Sontag's sentiments about literary criticism, voicing a concern about popular taste that David Foster Wallace would come to echo some half a century later:

I probably know as much about the essential qualities of good writing as anybody now discussing it. I do not discuss these things professionally for the simple reason that I do not consider it worthwhile. I am not interested in pleasing the intellectuals by writing literary criticism, because literary criticism as an art has in these days too narrow a scope and too limited a public, just as has poetry. I do not believe it is a writer's function to talk to a dead generation of leisured people who once had time to relish the niceties of critical thought. …. The reading public is intellectually adolescent at best, and it is obvious that what is called "significant literature" will only be sold to this public by exactly the same methods that are used to sell it toothpaste, cathartics and automobiles.

(One can only imagine how the era of Fifty Shades of Grey might stir Chandler's indignation.)

And though his opinion of "the public" might appear dismal, Chandler shares in E.B. White's belief in the responsibility of the writer to "lift people up, not lower them down." In a 1951 letter, he writes:

My theory has always been that the public will accept style provided you do not call it style either in words or by, as it were, standing off and admiring it. There seems to me to be a vast difference between writing down to the public (something which always flops in the end) and doing what you want to do in a form which the public has learned to accept.

In a March 1947 letter to the editors of Harper's, Chandler seconds H. P. Lovecraft's defiance to the distinction between "amateur" and "professional" writers, something all the more timely today in the age of democratized publishing:

There is not much point in all this pseudo-elaborate differentiation between the professional and the amateur. No such difference exists, or ever did. … All this talk about "pros" is itself sheer amateurism. There is no such thing as professionalism in writing.

In September of 1957, approaching his seventieth birthday, in a letter to Helga Greene, Chandler's last literary agent and subsequent heir, Chandler lists all his gripes about the superficialities of the literary world and concludes with what's perhaps his most poignant meditation on writing:

I haven't seen the New Yorker for months, just got tired of it. … But I think I may have become a bit crotchety from loneliness, worry, illness and physical suffering. My ideas of what constitutes good writing are increasingly rebellious. I may even end up echoing Henry Ford's verdict on history, and saying to unlistening ears: "Literature is bunk."

[…]I may satisfy myself with Richard II or a crime novel and tell all the fancy boys to go to hell, all the subtle-subtle ones that they did us a service by exposing the truth that subtlety is only a technique, and a weak technique at that; all the stream-of-consciousness ladies and gents, mostly the former, that you can split a hair fourteen ways from the deuce, but what you've got left isn't even a hair; all the editorial novelists that they should go back to school and stay there until they can make a story come alive with nothing but dialogue and concrete description: oh, we'll allow them one chapter of set-piece writing per book, even two, but no more; and finally all the clever-clever darlings with the fluty voices that cleverness, like perhaps strawberries, is a perishable commodity. The things that last – or should – I admit they sometimes miss – come from deeper levels of a writer's being, and the particular form used to frame them has very little to do with their value. The test of a writer is whether you want to read him again years after he should by the rules be dated.

And here we are today, reading Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler. Pair his wisdom with more insights on the written word fromKurt Vonnegut, Susan Sontag, Henry Miller, Stephen King, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Susan Orlean, Ernest Hemingway, and Zadie Smith.

No comments:

Post a Comment