"42"

Rotten Tomatoes: http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/42_2013/

Alan: I expected to like this movie and it exceeded my expectations. A deep centerfield homerun.

"The Deadly Oppression Of Black People: Best Pax Posts"

Jackie Robinson

Wikipedia

Righting the wrongs of '42'

Film gets important history wrong but leads to larger conversation

In 1989, as something of a social experiment in watching how film confronted America's deepest divides, I saw Spike Lee's "Do the Right Thing" on consecutive days. I was 20 then, a student at Temple University. The first showing was on a Friday night, a packed house on 15th and Chestnut streets in Philadelphia. It was a raucous scene, young whites and blacks leaving the film as they had watched it, at full decibel, electrified by the raw power of the searing images on the screen.

The next day, I took in the afternoon show at the Roxy on 20th and Sansom in Rittenhouse Square, the famous art house appealing to an older clientele, which watched the same movie that was playing so noisily just a few blocks away. When it was over, the majority of the audience stared solemnly at the screen until the final credits rolled, and left the theater just as they had watched it -- in total, stunned silence.

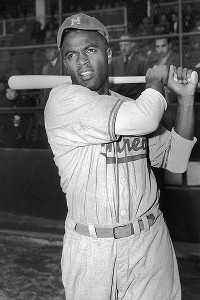

[+] Enlarge

Keystone/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesJackie Robinson played for the Montreal Royals in 1946.

There was "Malcolm X" in 1992 at the old Alexandria on Geary Street in San Francisco, where blacks and whites in the audience watched the film (and each other) uneasily as Spike Lee's opening montage contained the still raw, still fresh image of several Los Angeles Police Department officers mercilessly beating an unarmed Rodney King.

There were others. I skipped Steven Spielberg's "Amistad," but a few months ago, I sat in the theater and watched "Lincoln," amused that so many patrons, who must have been writing love notes to their sweethearts or making paper footballs instead of paying attention during 10th-grade history, were so gripped by the tension of the 13th Amendment vote. (Spoiler alert: It passed, which explains 1. why there's a 14th Amendment; 2. why the theater was integrated; and 3. why in part the president dies at the end of the movie.)

Last week, for "42," I continued the experiment, but this time with company. I took my 8-year-old -- just father and son. It was nice for once to look at his eyes, for it had been a while since he was in a theater not wearing 3D glasses. Fearful of what Hollywood would do with such an important piece of American history (while the term "false advertising" is redundant, the subtitle "The True Story of an American Legend" added exponentially to the cringe factor), I went into the theater with low expectations.

At this late date, Robinson lives in the chamber of American sainthood, what he symbolized far more important than the details of his life, or the price he paid for it. Like Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy, John Wayne and George Washington, Robinson is the embodiment of the famous credo from the great Western film "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance":

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

"42" felt like American history for Bolivians, an embarrassing commentary of how little the filmmakers believed their American audience would know of his story, made even sadder because they likely were correct. Sports films traditionally do poorly internationally, so the filmmakers were clearly targeting American moviegoers. The film was quite compelling for younger audiences; the kids in the audience seemed riveted by Robinson's charisma, his triumphant arc and the surface obviousness of his challenge.

Throughout the film, my son, who is of mixed race, would whisper questions, and the evening became part of a touching and bittersweet passage toward adulthood. Even though he's only in third grade, it was time to for me to say goodbye to the simpler stories of stuffed animals and Calvin and Hobbes, the perfectly manufactured insulation of childhood, and provide for him the answers he sought, answers that could not be presented with a pretty bow:

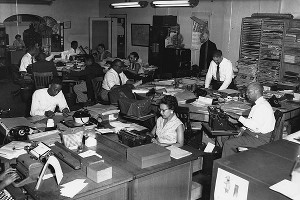

[+] Enlarge

FPG/Archive Photos/Getty ImagesIn 1946, the Pittsburgh Courier staff reached a national audience.

"Papa, what's Jim Crow?

What does the sign mean 'Colored?' What's 'Colored?'

Why are they doing this to him?

What's a Negro?" (to which I answered, "You.")

What does the sign mean 'Colored?' What's 'Colored?'

Why are they doing this to him?

What's a Negro?" (to which I answered, "You.")

The film grabbed him, and seeing him engrossed for two hours in a story where the protagonist did not have superpowers in turn grabbed me, even as what was on the screen lost me intellectually. The story isn't only the story but who is allowed to tell it. As the story progressed, the historical inaccuracies of "42" gnawed at me. Branch Rickey was given credit for integration of the game as his idea solely, when as early as 1943, the integration forces in government and the press (notably Lester Rodney of the Communist Party newspaper Daily Worker, Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy) had pressured baseball and other industries, such as the military, to integrate.

The film ignores the arrival two months after Robinson of Larry Doby to Cleveland as the American League's first black player, as well as of pitcher Dan Bankhead, baseball's first black pitcher, who happened to be Robinson's roommate with the Dodgers. Hollywood manufactured tension between Smith and Robinson and omitted both Robinson's 1945 tryout with the Boston Red Sox (where the Red Sox team humiliated him) and Robinson's triumphant 1946 season in Montreal (where Canadians accepted and cheered him, an important contrast to many Americans). The Canadian omission made me think of the film "Argo," which also unnecessarily minimized the Canadian influence and role in the Iranian hostage crisis.

The film's conventions were predictable and unnecessary, intellectually lazy, and showed little regard for baseball's African-American history. Early in the film, Smith introduces himself to Robinson, who acts as though he's never heard of the Pittsburgh Courier. In black America at that time, the Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier and Baltimore Afro-American were the leading black newspapers, shipped across the country. An athlete of Robinson's stature, especially one raised amid the segregated and parallel structures of American life, would have known of the Courier the way most people today have heard of Time magazine.

Smith had accompanied Robinson to the 1945 Red Sox tryout. In Robinson's autobiography, he wrote, "I will forever be indebted to Wendell because, without his even knowing it, his recommendation was in the end partly responsible for my career."

For the past week, the concepts of how a story is told and who gets to tell it have resonated as I thought about Boston and listened to complex conversation about war and terrorism devolve along the simplistic lines of "heroes" and "cowards" and "resilience." That simplification is a template borrowed from the tattered handbook of how there is generally one way to write about race in America: to make the majority of the mainstream feel good about itself without depth, without substance, without respect or appreciation for grievances that can successfully change society but that don't always have happy endings.

On August 30, 2003, I remember standing on the field at Fenway Park before a Yankees-Red Sox game and a man in the stands yelled at me and asked me to turn around. It was Spike Lee. We had never met, never spoken. He was holding a cell phone and handed it to me. On the other end was Ralph Wiley, the late and great author, former writer for the Oakland Tribune, Sports Illustrated, GQ and ESPN whose voice was so big and fearless and sharp it made you want to find your own.

After I handed the phone back to Spike, I asked him about the Jackie Robinson movie he had envisioned and I asked when it was finally coming to the big screen. I told him that a decade earlier, I responded to an ad he had placed in a baseball magazine looking for researchers for his Robinson film. He told me the film essentially died because he couldn't get the money people in Hollywood to finance it. For years after, I would think about how Hollywood could make "Harold and Kumar go to White Castle," but there would be no Jackie Robinson movie.

Watching "42" a decade later, conflicted by the gaping holes in the film but also accepting its value in terms of how it captivated my son, I couldn't help but wonder what Spike Lee's Jackie Robinson would've looked like on screen and how differently his life story would've been told from the African-American perspective (whether it was Lee's or another director's), that a people must be able to tell its own story, too.

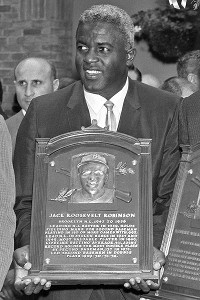

The Robinson story ended well for everyone -- except Jackie Robinson. On July 25, 1962, three days after barely being elected to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot, Robinson wrote to Walter O'Malley, owner of the Dodgers. Robinson had been retired six years and was outside of baseball. Nobody, not the Dodgers nor Branch Rickey, who had moved on to Pittsburgh and then St. Louis, offered him a job.

"I couldn't help but feel sad by the fact that the next day I was entering the Hall of Fame and I did not have any real ties with the game," Robinson wrote to O'Malley. "I thought back to my days at Ebbetts Field and kept wondering how our relationship had deteriorated. Being stubborn, and believing that it all stemmed from my relationship with Mr. Rickey, I made no attempt to find the cause. I assure you, Rae [Rachel Robinson] has on many occasions discussed this, and she too feels we should at least talk over our problems. Of course, there is the possibility that we are at an impasse, and nothing can be done. I feel, however, I must make this attempt to let you know how I sincerely regret we have not tried to find the cause for this breach …"

Sincerely yours,

Jackie Robinson

It is hard, if not impossible, to peel away only the first layer of the onion, which explains why it is often easier to avoid race as a subject or be offended if the conversation is anything more nuanced than "things are better now." For the next several days, in the car, at baseball practice, after bedtime reading, my son wanted not the first layer from the movie theater but the rest of the story.

I told him what I believed and that I was gratified that progress has been made, that his life is full of hope and possibility. I told him that the cartoonish villains -- especially the racist Phillies manager, Ben Chapman -- whom the entire theater of whites were laughing at and rooting against were not always the bad guys, but represented the normal American attitude for many years. For centuries, Chapman spoke for America, but today's America refuses to claim him.

It was also with sadness and a little bit of fear that I watched his face contort as I answered each question about Jim Crow, segregation and desegregation, about how Jackie Robinson and MLK and Rosa Parks weren't the only ones, about his school trip last year to Plimoth Plantation and the Wampanoags, and the rest ofthat story. I told him of yesterday and today.

As his brow furrowed, I asked him how many of his classmates looked like him or like me, how many times he saw people like us in restaurants or cartoons or movies. He was quiet and I knew I had darkened his mood. "That life does not have to be your life," I said. "And it won't." Then, he looked up and said, "Papa, when I get older, I'm going to do things that make the world better. I want to make sure everybody has the same chance, so no one has to go through what Jackie Robinson went through."

I smiled, and told him I was happy the movie was made because we were having this conversation. There was so much more, and we would discover all of it together. I told my boy the game had broken a piece of Robinson, aged him, killed him prematurely. Baseball honors him today, but during his life it praised him while simultaneously refused to hire him after he was done playing, despite everything he had done for it and America.

He asked me why this part, the rest of the Robinson story, wasn't in the movie. An 8-year-old could handle these truths but a country apparently couldn't. It was a good question, and I smiled a different smile. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. In Hollywood, saints aren't allowed to have tears.

No comments:

Post a Comment