What Would Reagan Really Do?

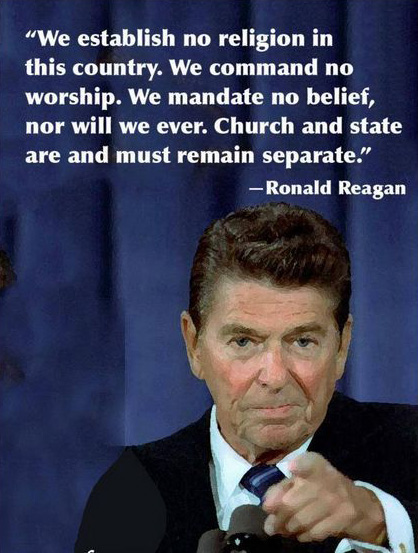

SOME REPUBLICANS WANT TO IMPOSE A REAGANITE PURITY TEST ON THIS FALL’S CANDIDATES. TODAY, THOUGH, THE 40TH PRESIDENT HIMSELF WOULDN’T PASS IT.

Grown men don’t tend to worship other grown men—unless, of course, they happen to be professional Republicans, in which case no bow is too deep, and no praise too fawning, for the 40th president of the United States: Saint Ronald Reagan.

His name is invoked by candidates for offices high and low, from aspiring state assemblyman Anthony Riley of Hesperia, Calif., who constantly referred to himself as a “Reagan Republican” before losing in the 59th district last month, to Danny Tarkanian of Nevada, who framed his failed 2010 primary run for the U.S. Senate as Reagan’s “last campaign” and frequently repeated what has to be one of the most tired lines in politics: “We’re going to win this one for the Gipper.”

For conservatives, Reagan is more than a president. He is a god of sorts: wise, just, omniscient, infallible. Being Republican has long meant being like Reagan—or at least saying you’re like Reagan. The writer Dinesh D’Souza neatly captured the conservative CW when he suggested that the right “simply need[s] to ask in every situation that arises: what would Reagan have done?” Period. Problem solved.

But as the rudderless Republican Party seeks to regain power in the Age of Obama, is WWRD (What Would Reagan Do?) really the smartest approach? Progressives, of course, would argue no. The world has changed dramatically since the 1980s, in no small part because of Reagan’s efforts as president. The top security threat of 2010 (Islamist terrorism) is not analogous to the top security threat of 1984 (Soviet communism). With China holding as much as $1.7 trillion in U.S. debt, the greatest danger posed by a communist state is no longer military: it’s economic. The tax burden now is far lighter than when Reagan took office. And deficits are a global problem rather than a merely national one. To address the challenges currently facing the country, a critic might say, Republicans can no longer simply do as Reagan did.

Such a critic would, incidentally, be correct. As The New Republic’s Jonathan Chait has written, politicians who conclude that “all wisdom resides in the canon of Reagan” too often abandon “the hard work of debate and self-examination and incorporating new facts.” It is pointless to toss Reagan’s vintage 1980s policy positions into the DeLorean and transport them, unaltered, to present-day Washington, D.C. Still, anyone who dismisses Reaganism as little more than a relic is forgetting an important fact: Reagan was the most successful Republican president since Teddy Roosevelt, and the only effective conservative leader of the last half century. Republicans who think Reagan is truth (and truth Reagan) may be overdoing it. But he’s still the GOP’s best model of how to win and how to lead.

The problem, then, is not that conservatives are searching for lessons in his record. It’s that they’re learning the wrong ones. In the years since Reagan left the White House, a vocal contingent of Republicans has sought to enforce current party orthodoxy—cut taxes at all costs; limit government spending (except defense); let the Bible be your guide—by insisting that Reagan was its source. But while these concepts often shaped Reagan’s campaign rhetoric, they didn’t define how he governed once in office. As a result, the Reagan that Republicans now revere—a mythical founder figure who always cut taxes, always rattled his saber, and always consulted Jesus—barely resembles the more pragmatic Reagan who actually ran the country. Only six months ago, the Republican National Committee considered subjecting all GOP candidates to a Reaganite purity test that Reagan himself would have failed.

“Reagan is a difficult icon for Republicans,” says biographer Lou Cannon. “He was an achiever and, by and large, a successful president. But he wasn’t a successful president in the way that the Republican hero worshipers describe him. Of course ideology was important to Reagan. But he was a success because of, and in spite of, ideology. He cared more about getting stuff done.”

To recapture the Reagan magic, Republicans must stop pining for some imaginary past and start asking how the real Reagan would “get stuff done” today. Some answers seem clear: he would’ve opposed Obamacare, refused to impose new regulations on the oil industry, and resisted the idea that government can spend its way out of a recession. But other questions are more vexing. Would a 21st-century Reagan cut taxes even further? Would he ramp up defense spending in response to terrorism (as he did with the Soviet Union)? How would he handle the rise of China? What about gay marriage? Immigration? By focusing on how Reagan’s actual methods, principles, and governing style would translate to today’s Washington, Republicans can take advantage of what he still has to offer (a successful model of conservative leadership) instead of clinging to what’s no longer relevant (a dated set of policies). Could a Reaganesque approach help today’s GOP? Absolutely. But first the GOP has to understand what a Reaganesque approach actually is.

It’s doubtful, for example, that a contemporary Reagan figure would seek to solve every problem by cutting taxes. In 1981, the former California governor swept into office promising to slash taxes to their lowest-ever levels—and with the Economic Recovery Tax Act, that’s exactly what he did. When Reagan arrived in the White House, the top marginal tax rate was 70 percent; by 1987 it was 38.5 percent (roughly the same as the rate under Bill Clinton). But while today’s conservatives continue to call for lower taxes in the name of the Gipper—Grover Norquist’s Americans for Tax Reform, for example, pressures Republicans to sign a “no new tax” pledge every election cycle—there’s simply no evidence in Reagan’s record to suggest that he would’ve followed his signature achievement by pushing for ever lower rates.

In fact, much the opposite. In 1982, Reagan agreed to restore a third of the previous year’s massive cut. It was the largest tax increase in U.S. history. In 1983, he raised the gasoline tax by five cents a gallon and instituted a payroll-tax hike that helped fund Medicare and Social Security. In 1984, he eliminated loopholes worth $50 billion over three years. And in 1986, he supported the progressive Tax Reform Act, which hit businesses with a record-breaking $420 billion in new fees. When it came to taxation, there were two Reagans: the pre-1982 version, who did more than any other president to lighten America’s tax burden, and his post-1982 doppelgänger, who was willing (if not always happy) to compensate for gaps in the government’s revenue stream by raising rates. Today, a truly Reaganesque leader would recognize (like Reagan) that the heavy lifting was finished long ago; last year, for instance, taxes fell to their lowest level as a percentage of personal income since 1950. And he would dial back the antitax dogma as a result.

In doing so, a 21st-century Reagan would free himself up to finish a bit of business that his predecessor never got around to: reducing the federal deficit. In the 1980 campaign, Reagan pledged to do three things if elected: lower taxes, win the Cold War, and curb government spending. But in his haste to achieve the first two goals, he abandoned the third. On his watch, federal employment grew by more than 60,000 (in contrast, government payrolls shrank by 373,000 during Clinton’s presidency). The gap between the amount of money the federal government took in and the amount it spent nearly tripled. The national debt soared from $700 billion to $3 trillion. And the United States was transformed from the world’s largest international creditor to its largest debtor.

Back then, Reagan avoided the tough decisions required to reduce the deficit; he was more concerned with confronting the Soviets and cutting taxes. But now that the Cold War is over and the top marginal tax rate is half of what it was in 1980, a real Reaganite no longer has any excuse to duck the country’s fiscal dilemma. In 2009, the Obama administration borrowed nearly 10 percent of GDP; this year the number will inch even higher. Even after the deficits decline in 2012, according to the Congressional Budget Office, they will still be higher than all but two of the shortfalls tallied under Reagan. As the bills for Social Security and Medicare come due—and voters, especially those on the right, demand action—Republicans have the opportunity to fulfill Reagan’s last, unkept promise by pushing for the kind of cuts (entitlement reform and defense rather than inconsequential “waste and fraud”) that he was never able to make.

Reagan worshipers will have a hard time stomaching the idea that lower defense spending could ever qualify as Reaganesque; after all, the Gipper increased the military’s funding by more than 40 percent during his time in office, disbursing $2.8 trillion overall. But there are two reasons to think that a contemporary Reagan might accept leaner defense budgets.

The first is that Reagan boosted defense spending for a specific historical reason: to force the poorer Soviet Union, which at one point was spending an unthinkable 40 percent of its annual budget on the military, to choose between wrecking its economy and ceding the arms race. Today, however, the threat Reagan was confronting (Soviet communism) no longer exists, and what’s replaced it (the asymmetrical war against Islamist terrorism) requires a response that relies on soft power and surgical strikes rather than overwhelming military force, especially as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wind down. While the rise of China is also a concern, the challenge there is more fiscal than military. Scaling back our spending—and therefore our debts to Beijing—would actually shift the balance of power back toward Washington; we currently shell out seven times as much as China on defense, so the risk of falling behind is negligible. Even Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who served in Reagan’s CIA, grasps the new calculus, which is why he recently told Congress to halt the explosive growth of the military’s budget by freeing up $100 billion in waste and overhead. The bipartisan Sustainable Defense Task Force, meanwhile, has recommended $1 trillion in cuts. During the 1980s, Reagan made sure the size of the military—by far the largest recipient of discretionary spending—matched the needs of the moment. A Reaganesque leader would do the same now, especially with record deficits looming.

The second reason is that despite his hawkish rhetoric, Reagan almost always resisted using brute force against America’s enemies. With the Soviet Union on the ropes, the president spent his second term angering conservatives and confusing his own advisers by pursuing his “dream” of a nuclear-free world with his “friend” Mikhail Gorbachev in a series of dovish summits that enabled the Soviet leader to make the internal reforms required to end the Cold War. “I bet the hardliners in both our countries are bleeding when we shake hands,” Reagan whispered at one of their meetings. He rejected calls from conservatives like Norman Podhoretz, William F. Buckley, and Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams to send U.S. troops into Nicaragua, El Salvador, or Panama, saying, “Those sons of bitches won’t be happy until we have 25,000 troops in Managua, and I’m not going to do it.”

Reagan was particularly reluctant to engage with terrorists and other aggressors. He tried to free Hizbullah’s American hostages by selling missiles to its patrons in Iran. He used strong words when the Soviets shot down a Korean Airlines flight over Siberia (“savagery,” “murderous”) but told his advisers that “vengeance isn’t the name of the game” and refused to suspend upcoming arms-control negotiations in Geneva. He never got around to retaliating for the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, and when Shia fighters attacked the nearby Marine barracks a few months later, he quickly withdrew all remaining troops from Lebanon. If “you’re not quite sure a retaliation would hit the people who were responsible for the terror and the crime, and you might be killing innocent people,” he said, “you swallow your gorge and don’t do it.” Podhoretz & Co. criticized him for having “cut and run,” but the president recognized that battling terrorists in a civil war wasn’t in the United States’ best interest. A contemporary Reaganite would acknowledge the same reality and couple tough talk with pragmatic actions in places like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and North Korea while adjusting defense spending accordingly.

Although the mythologizers might disagree, a Reaganesque approach to social issues would be similarly nuanced. Reagan was a religious man, and his bond with fellow born-again Christians enabled his election and forever altered the GOP. But while he was personally opposed to things like homosexuality and abortion, he almost never let his religious views dominate his policies. (HIV/AIDS was a notable exception.) In 1967, Governor Reagan signed a law in California that legalized millions of abortions. In 1978, he opposed California’s Proposition 6 ballot initiative, which would’ve barred gay men and women from working in public schools. As president, he was perfectly willing to anger Jerry Falwell and the religious right by choosing a Supreme Court nominee, Sandra Day O’Connor, whose pro-life credentials were in doubt; he simply cared more about appointing a woman. When he addressed right-to-life rallies, it was always remotely, by video. He even became the first president to host an openly gay couple overnight at the White House. So while Republicans claim that a constitutional amendment to “protect marriage” would represent the height of Reaganism, the Gipper’s actual record suggests that a true heir would keep his distance on social issues.

By refusing to spend his political capital on gay marriage and abortion, a 21st-century Reagan would be free to tackle a problem he might actually solve: illegal immigration. In 1986, Reagan addressed the issue directly by signing the Immigration Reform and Control Act—a measure that granted amnesty to millions of aliens but also included tough provisions for bringing illegal immigration to an end (a 50 percent increase in border guards; a requirement that employers attest to their workers’ legality). Unfortunately, the guards didn’t slow the tide of immigrants, and U.S. businesses quickly outsourced their hiring to subcontractors.

Today, Reagan’s mythologizers cite these failures as evidence that a contemporary Reagan would focus solely on border security while opposing any pathways to citizenship. But that’s misleading. As Reagan speechwriter Peter Robinson recently noted in The Wall Street Journal, “Reagan dismissed ‘the illegal alien fuss’ ” and “again and again declared that a basic, even radical, openness to immigration represents a defining aspect of our national identity.” A canny politician, he would’ve sought to woo “the children and grandchildren of immigrants who entered the country from Mexico,” according to Robinson—both “as a matter of principle” and because he “recognized that Republicans face a[n electoral] math problem” without Latino support. Today, Reagan would probably aim to rectify the failures of 1986 with stricter border security while also promising the sort of reform—a long but explicit path to citizenship; a guest-worker program—that George W. Bush and John McCain first proposed in 2004–05. The start of the second stage might be contingent on the success of the first. But it would remain part of the plan.

For Republicans, Reagan is still relevant. But worshiping his myth—and pretending that his campaign promises and rhetoric represent his entire legacy—won’t help the GOP chart a path back to power. To do that, a new generation of leaders should study how the Gipper actually governed, then modernize his approach for today’s world. The result would be an optimistic, forward-looking politics centered on a few key priorities: reducing the deficit, matching military spending to current challenges, solving the immigration puzzle. It wouldn’t be an exact replica of Reagan’s 1980 platform. But it would be Reaganesque.

Right now, few Republicans have embraced this renewed Reaganism; Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels—a former Reagan staffer who’s raised taxes when necessary and who recently suggested that a “truce in the culture wars” would help Washington balance the budget—probably comes closest. But he’s no match for Reagan in the charisma department. To leave 1981 behind, Republicans will need more than an updated list of policy proposals; they’ll need a leader like Reagan—sunny, determined, sui generis—to sell it. Let the search for a new saint begin.

No comments:

Post a Comment