Sarah Palin, Socialist Super Star.

Don't think so?

***

Trouble In Mitt Romney's Socialist Hospital Paradise

Posted: 10/27/2012

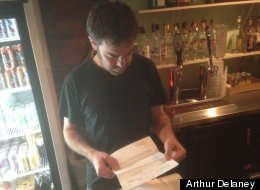

Washington bartender Mike Boone looks over one of the hospital bills he received after suffering multiple stab wounds fighting off a mugger.

WASHINGTON -- In the early hours of May 1, D.C. bartender Mike Boone came to the aid of a young woman who was being mugged.

Boone had offered to walk her home from the bar, Trusty's on Capitol Hill, since the immediate neighborhood is not known for having the safest streets at night. A man jumped from behind some bushes and grabbed the woman's purse. Boone also grabbed it, and the two men started fighting.

"We were punching each other pretty hard," Boone recalled. It wasn't until blood gushed from his body and the woman screamed that the bartender realized what had really happened.

"He was punching me with a knife," Boone said.

Boone passed out on the sidewalk. He woke up the next day in a hospital bed, recovering from eight stab wounds and a collapsed lung.

Like nearly 50 million other Americans, Boone lacked health insurance. A pre-existing condition -- in his case, a broken back he suffered in 1993 -- prevented him from obtaining affordable coverage. President Barack Obama's health care law prohibits insurance companies from discriminating against people with pre-existing conditions, but that reform doesn't go into effect for adults until 2014.

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney has vowed to repeal the health care law entirely if he's elected. In America, Romney has said, we don't let people die in the street simply because they lack health insurance: Hospitals are there to care for the uninsured.

Indeed, the health care system did not let Boone bleed to death on the sidewalk. But it did bury him in life-altering debt. After four days in the hospital and two surgeries, the 39-year-old -- hailed as a hero on Capitol Hill and beyond for his actions -- is staring at $60,000 in medical bills so far. And they haven't stopped rolling in."We don't have a setting across this country where if you don't have insurance, we just say to you, 'Tough luck, you're going to die when you have your heart attack,'" Romney said in an interview with The Columbus Dispatch on Oct. 11. "No, you go to the hospital, you get treated, you get care, and it's paid for, either by charity, the government or by the hospital."

Well-wishers, moved by media reports of his story, have donated $17,000 to help Boone cover his expenses, and he's hoping a public fund for crime victims could defray as much as $25,000 more. But Boone, who said he expects to earn only about $15,000 this year, figures he'll still be looking at nearly $20,000 in debt, all for risking his life for a fellow human being.

His story is one that plays out with troubling regularity in the bar-and-restaurant business, where a high quotient of workers go without health coverage. Post-tragedy fundraisers are common in the industry. The events serve as vivid examples of the private sector's safety net in action.

These fundraisers can defray some of the costs of emergency care, as they have done for Boone, but often they don't provide nearly enough. Paying for health care isn't as efficient or just as Romney suggests. Instead, much of the cost is borne by health care providers and insurers and, ultimately, the insured. We all pay.

"At first, I was like, man, this is really great, this could take care of it," Boone said of the charity he has received. "And then the big bills started coming."

A FORM OF SOCIALISM

Douglas Zehner is the senior vice president and chief financial officer at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in northwest Washington, where Boone was treated. He said Medstar gave $22.1 million worth of care to uninsured or underinsured patients and forgave $85.1 million in debt last year. But that charity isn't free. The only way the hospital can recoup its losses, Zehner said, is by negotiating with private insurance providers for higher prices, a process known as "cost-shifting."

"I have to price my services with insurance carriers because that’s the only group I'm even in the room talking to about how much they're going to pay me for my services," Zehner said. "So the way the cost-shifting works is you basically back into how much [money] you need to run that service [for all patients] and apply it to the expected number of people that are coming in that have insurance to get that service."

The fewer people who have insurance, the greater the burden on those who do have coverage. In order to cover the costs of treating the uninsured, premiums go up. The American Hospital Association estimated that U.S. hospitals performed $39.3 billion worth of uncompensated care in 2010, the most recent year for which numbers are available. That's 5.8 percent of total expenses.

This is a problem that Obama's health care law seeks to address and one that Romney himself has acknowledged in the past, before he began pursuing the Republican presidential nomination.

"Look, it doesn't make a lot of sense for us to have millions and millions of people who have no health insurance and yet who can go to the emergency room and get entirely free care for which they have no responsibility, particularly if they are people who have sufficient means to pay their own way," he said in 2010.

In 2007, he used even starker language: "When [uninsured people] show up at the hospital, they get care. They get free care paid for by you and me. If that's not a form of socialism, I don't know what is."

Boone, who considers himself relatively apolitical, said he "absolutely" looks forward to the full implementation of Obamacare. "I'm so excited that this is happening," he said.

Given his pre-existing condition, Boone said, the cost of purchasing individual health insurance was astronomical. If an insurer even made him an offer, he said, he was seeing quotes of $1,000 per month -- far beyond what he could afford. Under Obamacare, Boone should be able to find an affordable plan on the new health care "exchanges" being established in 2014.

It's not a done deal, however. Although it's unlikely that Congress will have the Republican majorities required to approve a full repeal, a Romney presidency would have ways to hobble the law's implementation, jeopardizing coverage for people like Boone.

Romney has provided few details about what he would put in place of Obamacare, other than suggesting during one debate that he would protect people with pre-existing conditions from losing health insurance. His plan would do nothing for the uninsured. But Romney has repeated his line that hospitals will be there to treat those people.

"Well, we do provide care for people who don't have insurance," he said in an interview with "60 Minutes" in September. "If someone has a heart attack, they don't sit in their apartment and die. We pick them up in an ambulance and take them to the hospital and give them care."

Romney has not explained his contradictory statements about the value of giving emergency room care to the uninsured, and his campaign did not respond to a request for additional information.

But it turns out emergency room care for the uninsured is a less-than-ideal form of socialism.

CHARITY'S LIMITS

The way that health care plays out in the restaurant industry shows the limits of charity in defraying the cost of hospital visits.

According to the National Restaurant Association, the industry employs nearly 10 percent of the U.S. workforce and has outperformed the broader economy during the past decade. While precise data on health insurance for service industry workers are hard to come by, surveys by the Restaurant Opportunities Center, an advocacy group for restaurant workers, have found that 90 percent of workers don't receive health coverage through their employer.

"It's absolutely the industry standard" for bars not to cover their employees, said Mark Menard, who co-owns Trusty's, where Boone works, and three other Washington bars.

Menard said it would be prohibitively expensive to insure all of his workers, and he estimated that one-third to one-half of his employees buy their own insurance on the individual market.

Bar patrons in Washington and other cities have repeatedly come out in support of industry employees who have been in car crashes or attacked after closing and don't have adequate health coverage. Because these employees often work without the benefit of sick leave or workers' compensation, they suffer lost wages on top of crushing medical debt.

On Oct. 14, for instance, Penn Social, a downtown D.C. bar, held a fundraiser for two uninsured staffers who were horrifically injured when a drunk driver in a Jeep Cherokee smashed into their Honda Civic while they were waiting at a red light. The collision was so severe that the Civic's gas tank ruptured, causing a fire.

"The men in the Civic remain hospitalized with myriad internal injuries and burns,"The Washington Post reported. "The driver, from Virginia, suffered bleeding from the brain, broken ribs, a punctured lung, damage to his spleen and kidneys, and third-degree burns over 17 percent of his body. His passenger, a cousin, has third-degree burns over nearly 40 percent of his body."

Friends of the two men have started a recovery fund.

Employees and patrons of the Argonaut bar in Washington hosted a fundraiser in 2006 for a bartender who was shot in the head after leaving work. The bartender survived but lost an eye.

Boone's medical bills have wiped out his personal savings. He's already receiving letters from collection agencies, and he said his credit has been ruined.

"Buying a sailboat -- that was the plan," Boone said recently from behind the bar, holding up the tip jar he once considered his boat fund. "I was ready to go buy the sailboat. Then I got stabbed."

"Buying a sailboat -- that was the plan," Boone said recently from behind the bar, holding up the tip jar he once considered his boat fund. "I was ready to go buy the sailboat. Then I got stabbed."

Now he's hoping to buy a boat and live in it, he said, "so I can rent a slip and have cheaper rent."

He missed nearly three months of work before returning to his job near the end of July. Along with that tip jar, he now has letters of support and a stack of hospital bills at the bar.

Given that he'd risked his life to help a patron, Boone was a particularly good candidate for a community fundraiser. Days after he left the hospital, a charity night at Trusty's and a PayPal account pulled in $17,000 to go toward his medical bills. A line stretched down the block, as people who'd never been to the bar before showed up to meet him.

It was a moving show of support, and Boone said he found himself stepping outside throughout the night to smoke and calm himself. He tried to enjoy it all, but he'd rather not have to rely on the generosity of others to make ends meet.

"It sucked," he said. "I cried."

The charitable contributions helped cover his rent and food while he missed work, Boone said. He's still waiting to find out exactly how much he owes the hospital. He doesn't know whether he arrived at the emergency room by ambulance or helicopter. He figures the bill will tell him.

***