Excerpt from "Senator Jim Webb's

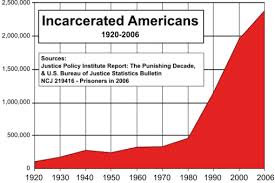

Criminal Justice Crusade" - "In 1980, fewer than 500,000

Americans were in prison; today, the number is 2.3 million. To put that

statistic in perspective, the median incarceration rate among all countries is

125 prisoners for every 100,000 people. In England, it’s 153; Germany, 89;

Japan, a mere 63. In America, it’s 743, by far the highest in the world.

Include all the U.S. residents currently on probation or parole, and our

country’s correctional population soars to about 7.2 million—roughly one in

every 31 Americans. All told, the U.S. incarcerates nearly 25 percent of the

world’s prisoners, even though it’s home to only 5 percent of the world’s

inhabitants. The cost of our prison addiction is staggering. In recent

years, America’s total criminal-justice tab—state, local, and federal—has

ballooned to more than $200 billion a year."

Every text, without a context, is a pretext.

Senator Jim Webb's "Criminal Justice Crusade" and "The Caging of America" by Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker - provide disturbing insight into the counterproductive and bank-breaking penal colony we have created from motives as mixed as biblical vengeance and stock market profitability. (George Will recently wrote that it now costs about $35,000.00 a year to imprison someone. Stars and Stripes Magazine says that the annual cost of a prisoner at Guantanamo is $800,000.00, yes, eight hundred thousand dollars -

Read either article below and you will never again look at America's prisons the way you do now.

Read both articles and your espistemological suppositions about "The True" and "The Good" will crumble.

***

Jim Webb’s Criminal-Justice Crusade

One in 31 Americans is lost in the criminal-justice system. As his senate career winds down, Webb is determined to change that.

Jim Webb is in jail. This is not because an aide to the combustible Virginia senator was caught carrying his boss’s loaded 9mm semiautomatic pistol into a congressional office building, which actually happened in 2007. Nor is it because Webb “slugged” President Bush on a White House receiving line, which he was once reportedly tempted to do. Today’s visit is voluntary—and that’s why it’s so remarkable.As Republicans in Washington waste yet another summer afternoon whining about Democrats, and Democrats play rubber to their glue, Webb has skipped town and driven west, 30 minutes down I-66, to Fairfax County’s juvenile detention center. There are no TV crews to dazzle. No local leaders to praise. And no voters to persuade. Just Webb doing what he’s been doing for nearly three decades now: touring a prison and asking a lot of questions.

Webb is as much a hero as any nonfictional person can be. In 1969, he shielded a fellow soldier from a grenade and caught a back full of shrapnel as he singlehandedly destroyed three Viet Cong bunkers, earning a Navy Cross for his valor. (He later wrote several novels about the war.) But what Webb has accomplished over the past two years has been as brave, in its own quiet way, as what he did that day in the An Hoa Basin: he has transformed criminal-justice reform from a fringe concern—an issue his own advisers called “political suicide,” he tells Newsweek—into a real possibility. “Once a kid is incarcerated, that’s it for him,” Webb says. “We need smarter ways of dealing with people at apprehension, and even whether you decide to arrest. The types of courts they go into—drug courts, as opposed to regular courts. How long you sentence them. How you get them ready to return home.”

Jim Webb, Khue Bui for Newsweek

Webb, a law-and-order type who once derided affirmative action as “state-sponsored racism,” is an unlikely crusader for a cause typically championed by civil-rights activists and drug-war opponents. And yet, in 2009, the senator introduced legislation that would create the first comprehensive national review of crime policy in 45 years—legislation that he has been fighting, with plenty of “stress, insanity, and gnashing of teeth,” as one aide puts it, to pass, in vain, ever since. Now Webb, who recently announced that he will not seek a second term in 2012, thinks he may have finally found his moment. “The timing is right,” says Jeremy Travis, president of John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “We have millions of people in prison when states are struggling to balance their budgets, and, for the first time, a vibrant, nonideological middle ground on crime policy. This is a moral and fiscal problem now.”

Hence Webb’s field trip to Fairfax. As the superintendent flaunts his pet innovations—a family-style cafeteria, two-teacher classrooms, a teen lending library—the senator nods his approval, fists clenched, jaw jutting, grumbling an occasional query. Part of him, however, is somewhere else. At one point, Webb spots some speakers on the wall (for eavesdropping), and returns, as he often does, to Vietnam, noting how Saigon’s Rex Hotel had a similar setup. But the place he can’t stop thinking about, the place that really gnaws at him, isn’t quite so far away. Along one carpeted, sunlit hallway—the facility looks more like a suburban middle school than a prison—Webb pauses and turns to his tour guide.

“Ever been to the Richmond city jail?” he asks, referring to Virginia’s most notorious (and notoriously overcrowded) prison, where one inmate recently died of heat exposure and others were busted dealing heroin. “This is the same state. But I have visited at least a dozen prisons in my life, and I’ve never seen anything as bad. Go from there to here, and it’s like two different countries.”

There are two types of people in America: those, like Webb, who think the criminal-justice system desperately needs to be fixed, and those who haven’t been paying attention. In 1980, fewer than 500,000 Americans were in prison; today, the number is 2.3 million. To put that statistic in perspective, the median incarceration rate among all countries is 125 prisoners for every 100,000 people. In England, it’s 153; Germany, 89; Japan, a mere 63. In America, it’s 743, by far the highest in the world. Include all the U.S. residents currently on probation or parole, and our country’s correctional population soars to about 7.2 million—roughly one in every 31 Americans. All told, the U.S. incarcerates nearly 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, even though it’s home to only 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants.

The cost of our prison addiction is staggering. In recent years, America’s total criminal-justice tab—state, local, and federal—has ballooned to more than $200 billion a year, draining government resources at the worst possible moment. Meanwhile, millions of men—fathers, brothers, wage earners—have been consigned to a vicious cycle of absence, stigmatization, and recidivism. If you’re black and you haven’t finished high school, you now have a 60 percent chance of going to jail—an experience that will reduce your annual employment by nine weeks and lower your yearly earnings by 40 percent. As Webb likes to put it, “Either we have the most evil people on earth living in the U.S., or we are doing something dramatically wrong in terms of how we approach the issue of criminal justice.”

The answer, of course, is the latter. Americans aren’t 12 times as evil as the Japanese, and they certainly aren’t any more evil than they were in 1980. The truth is that America’s three-decade-long incarceration boom hasn’t “really [been] about increasing crime” at all, as Allen J. Beck of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, recently admitted—it’s been about “how we chose to respond to crime.” In 1986, President Reagan signed a $1.7 billion bill that created mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses, and “when you increase the likelihood of a person going to prison for a conviction, and then you increase how long you keep them there,” Beck explained, “it has a profound effect.” In this case, Reagan’s legislation, and an epidemic of similar state laws passed around the same time, sparked a 1,200 percent increase in the number of people jailed for drug violations, most of whom have been low-level users with no history of violence or dealing, and most of whom have been black. Today, African-Americans represent 74 percent of those sent to prison for drug possession, even though they make up only 14 percent of users.

The abysmal condition of our criminal-justice system is mortifying on many fronts: fiscal, moral, social. But our knottiest problem is political. While there is no shortage of solutions to America’s incarceration overload—state and local authorities have spent years experimenting with innovative sentencing and reentry programs—politicians have developed an allergy to any reform that could get them tagged as “soft on crime.” They’re afraid of becoming Michael Dukakis.

Webb is the exception. In 1984, he traveled to Japan to report a story forParade magazine about an American citizen imprisoned for two years for pot possession. Despite the draconian sentence, Webb concluded that Japan’s system was still fairer than ours. “At the time, we had 600,000 people in jail,” he says. “But even with half our population, Japan had only 40,000.” A military man by trade and tradition, Webb had always been “interested in preserving fairness while also preserving discipline.” Now he began to wonder if America’s metastasizing prison-industrial complex could ever strike the same balance. By the time he ran for the Senate in 2006, Webb had decided to make criminal-justice reform one of his signature issues. “I got a lot of advice not to talk about it,” he says. “But no matter where I went, heads would nod. People understood that our system had gone too far.”

The trick was figuring out how a single senator could rein it in. Soon after arriving in Washington, Webb proposed and passed a new bipartisan GI bill, despite opposition from President Bush—a significant achievement for a junior member. Emboldened, he quickly ruled out a piecemeal approach to criminal-justice reform, citing the long clash over crack sentencing as a cautionary tale. “The problem with Congress is that you can get stalled solving any one small aspect of this problem,” Webb says. “Crack alone took 16 years.” At the same time, he reasoned that sweeping legislation would polarize rather than galvanize, and would become a target for Republicans and an albatross for Democrats. Webb settled, instead, on a stepping-stone strategy: a bipartisan panel tasked with conducting a head-to-toe review of the U.S. criminal-justice system and then recommending cost-effective, data-driven, state-based reforms. Asked about the obvious objection—that legislators will simply ignore whatever inconvenient truths his blue-ribbon board exhumes—Webb is unmoved. “We’re not looking for a debating society here,” he snaps. “This is a $14 million bet. And the alternative—addressing one piece at a time—doesn’t work.”

For the past two and a half years, Webb’s legislation has lingered in Senate limbo; Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn blocked the initial version, and a later iteration was included in last year’s failed omnibus spending package. (A mirror bill passed the House in 2010.) But time may be on Webb’s side. Initially, conservatives “assumed this was all about drugs,” the senator says, “so there was hesitation.” As the recovery faltered, however, Republicans began to realize that prison spending, which is the fastest-growing state budget item behind Medicaid, was ripe for a trim. As a result, influential GOP governors such as Bobby Jindal and Mitch Daniels are now working to reduce recidivism, soften sentences, and save money in their home states, while Right on Crime, a new conservative group backed by Newt Gingrich, Jeb Bush, and Grover Norquist, is championing reform on the national stage. “People who would’ve been skeptical have gotten on board,” says Webb, noting that he has convinced Republican Sens. Lindsey Graham, Jeff Sessions, and Orrin Hatch to support his bill. “And deficits brought them in.” The fact that America’s violent-crime rate has continued to decline during the recession—it’s now at its lowest level in 40 years—only helps Webb’s cause, as does his looming retirement. “There was a lot of concern among Republicans about whether passing this bill would help me win reelection,” he says, grinning. “So that’s off the table.”

As Webb wanders through the Fairfax detention center, he can’t help but marvel at its most impressive achievement: the Post-D (or Dispositional) Program. To minimize recidivism, the Fairfax facility funnels 11 nonviolent detainees into a separate wing of the building, where they receive up to six months of therapy and substance-abuse treatment, followed by six months of postconfinement “aftercare.” “[Fairfax has] 110 beds but only 45 kids,” Webb says. “You treat the people who need to be treated and incarcerate the people who need to be incarcerated.” One “graduate” now works at the CIA; another is employed at the detention center itself.

Webb is reluctant to discuss his vision for the criminal-justice system—he’d rather his commission come to its own conclusions—but when pressed, he paints a picture that resembles the facility he’s touring today: parole and probation policies that no longer drive hundreds of thousands of people back to jail every year for nonthreatening, technical violations; work-release programs, educational opportunities, and looser custody levels for prisoners preparing to reenter society; and, most important, fewer arrests and shorter sentences for nonviolent drug users. “Drug convictions are like playing Russian roulette,” Webb says. “Usage is pretty wide, and yet the people who are convicted carry a stigma for the rest of their lives.”

Webb believes he has “two thirds” of the Senate on his side, and that his only remaining roadblock is “getting the bill to the floor.” He’s probably right: so far, his plan has earned the backing of 39 cosponsors and more than 100 outside organizations, including the National Sheriff’s Association, and President Obama has been “supportive.” (In February they “discussed doing it as a presidential commission” should the bill fail.) But even if the National Criminal Justice Commission Act were to pass tomorrow, its author would leave office long before any recommendations rolled in. The timing suggests a last crusade of sorts: an old soldier’s final fight. On his way out of the Fairfax facility, Webb dismisses this interpretation with a characteristic grunt. “I don’t do last acts,” he says. But it is clear, as he continues, that criminal-justice reform has, for him, become something larger than just another piece of legislation. “I didn’t do this for political reasons,” Webb says. “I’m a novelist, basically. What do you do with a novel? You take a complex issue and you think your way through it. I’ve taken on the same types of issues as a senator and worked to sort them out. This is one that needs to be done.”

***

(N.B. It takes a few paragraphs to get into the rhythm of Gopnik's prose.)

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2012/01/30/120130crat_atlarge_gopnik

Six million people are under correctional supervision in the U.S.—more than were in Stalin’s gulags. Photograph by Steve Liss.

A prison is a trap for catching time. Good reporting appears often about the inner life of the American prison, but the catch is that American prison life is mostly undramatic—the reported stories fail to grab us, because, for the most part, nothing happens. One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich is all you need to know about Ivan Denisovich, because the idea that anyone could live for a minute in such circumstances seems impossible; one day in the life of an American prison means much less, because the force of it is that one day typically stretches out for decades. It isn’t the horror of the time at hand but the unimaginable sameness of the time ahead that makes prisons unendurable for their inmates. The inmates on death row in Texas are called men in “timeless time,” because they alone aren’t serving time: they aren’t waiting out five years or a decade or a lifetime. The basic reality of American prisons is not that of the lock and key but that of the lock and clock.

That’s why no one who has been inside a prison, if only for a day, can ever forget the feeling. Time stops. A note of attenuated panic, of watchful paranoia—anxiety and boredom and fear mixed into a kind of enveloping fog, covering the guards as much as the guarded. “Sometimes I think this whole world is one big prison yard, / Some of us are prisoners, some of us are guards,” Dylan sings, and while it isn’t strictly true—just ask the prisoners—it contains a truth: the guards are doing time, too. As a smart man once wrote after being locked up, the thing about jail is that there are bars on the windows and they won’t let you out. This simple truth governs all the others. What prisoners try to convey to the free is how the presence of time as something being done to you, instead of something you do things with, alters the mind at every moment. For American prisoners, huge numbers of whom are serving sentences much longer than those given for similar crimes anywhere else in the civilized world—Texas alone has sentenced more than four hundred teen-agers to life imprisonment—time becomes in every sense this thing you serve.

For most privileged, professional people, the experience of confinement is a mere brush, encountered after a kid’s arrest, say. For a great many poor people in America, particularly poor black men, prison is a destination that braids through an ordinary life, much as high school and college do for rich white ones. More than half of all black men without a high-school diploma go to prison at some time in their lives. Mass incarceration on a scale almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country today—perhaps the fundamental fact, as slavery was the fundamental fact of 1850. In truth, there are more black men in the grip of the criminal-justice system—in prison, on probation, or on parole—than were in slavery then. Over all, there are now more people under “correctional supervision” in America—more than six million—than were in the Gulag Archipelago under Stalin at its height. That city of the confined and the controlled, Lockuptown, is now the second largest in the United States.

The accelerating rate of incarceration over the past few decades is just as startling as the number of people jailed: in 1980, there were about two hundred and twenty people incarcerated for every hundred thousand Americans; by 2010, the number had more than tripled, to seven hundred and thirty-one. No other country even approaches that. In the past two decades, the money that states spend on prisons has risen at six times the rate of spending on higher education. Ours is, bottom to top, a “carceral state,” in the flat verdict of Conrad Black, the former conservative press lord and newly minted reformer, who right now finds himself imprisoned in Florida, thereby adding a new twist to an old joke: A conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged; a liberal is a conservative who’s been indicted; and a passionate prison reformer is a conservative who’s in one.

The scale and the brutality of our prisons are the moral scandal of American life. Every day, at least fifty thousand men—a full house at Yankee Stadium—wake in solitary confinement, often in “supermax” prisons or prison wings, in which men are locked in small cells, where they see no one, cannot freely read and write, and are allowed out just once a day for an hour’s solo “exercise.” (Lock yourself in your bathroom and then imagine you have to stay there for the next ten years, and you will have some sense of the experience.) Prison rape is so endemic—more than seventy thousand prisoners are raped each year—that it is routinely held out as a threat, part of the punishment to be expected. The subject is standard fodder for comedy, and an uncoöperative suspect being threatened with rape in prison is now represented, every night on television, as an ordinary and rather lovable bit of policing. The normalization of prison rape—like eighteenth-century japery about watching men struggle as they die on the gallows—will surely strike our descendants as chillingly sadistic, incomprehensible on the part of people who thought themselves civilized. Though we avoid looking directly at prisons, they seep obliquely into our fashions and manners. Wealthy white teen-agers in baggy jeans and laceless shoes and multiple tattoos show, unconsciously, the reality of incarceration that acts as a hidden foundation for the country.

How did we get here? How is it that our civilization, which rejects hanging and flogging and disembowelling, came to believe that caging vast numbers of people for decades is an acceptably humane sanction? There’s a fairly large recent scholarly literature on the history and sociology of crime and punishment, and it tends to trace the American zeal for punishment back to the nineteenth century, apportioning blame in two directions. There’s an essentially Northern explanation, focussing on the inheritance of the notorious Eastern State Penitentiary, in Philadelphia, and its “reformist” tradition; and a Southern explanation, which sees the prison system as essentially a slave plantation continued by other means. Robert Perkinson, the author of the Southern revisionist tract “Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire,” traces two ancestral lines, “from the North, the birthplace of rehabilitative penology, to the South, the fountainhead of subjugationist discipline.” In other words, there’s the scientific taste for reducing men to numbers and the slave owners’ urge to reduce blacks to brutes.

William J. Stuntz, a professor at Harvard Law School who died shortly before his masterwork, “The Collapse of American Criminal Justice,” was published, last fall, is the most forceful advocate for the view that the scandal of our prisons derives from the Enlightenment-era, “procedural” nature of American justice. He runs through the immediate causes of the incarceration epidemic: the growth of post-Rockefeller drug laws, which punished minor drug offenses with major prison time; “zero tolerance” policing, which added to the group; mandatory-sentencing laws, which prevented judges from exercising judgment. But his search for the ultimate cause leads deeper, all the way to the Bill of Rights. In a society where Constitution worship is still a requisite on right and left alike, Stuntz startlingly suggests that the Bill of Rights is a terrible document with which to start a justice system—much inferior to the exactly contemporary French Declaration of the Rights of Man, which Jefferson, he points out, may have helped shape while his protégé Madison was writing ours.

The trouble with the Bill of Rights, he argues, is that it emphasizes process and procedure rather than principles. The Declaration of the Rights of Man says, Be just! The Bill of Rights says, Be fair! Instead of announcing general principles—no one should be accused of something that wasn’t a crime when he did it; cruel punishments are always wrong; the goal of justice is, above all, that justice be done—it talks procedurally. You can’t search someone without a reason; you can’t accuse him without allowing him to see the evidence; and so on. This emphasis, Stuntz thinks, has led to the current mess, where accused criminals get laboriously articulated protection against procedural errors and no protection at all against outrageous and obvious violations of simple justice. You can get off if the cops looked in the wrong car with the wrong warrant when they found your joint, but you have no recourse if owning the joint gets you locked up for life. You may be spared the death penalty if you can show a problem with your appointed defender, but it is much harder if there is merely enormous accumulated evidence that you weren’t guilty in the first place and the jury got it wrong. Even clauses that Americans are taught to revere are, Stuntz maintains, unworthy of reverence: the ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” was designed to protect cruel punishments—flogging and branding—that were not at that time unusual.

The obsession with due process and the cult of brutal prisons, the argument goes, share an essential impersonality. The more professionalized and procedural a system is, the more insulated we become from its real effects on real people. That’s why America is famous both for its process-driven judicial system (“The bastard got off on a technicality,” the cop-show detective fumes) and for the harshness and inhumanity of its prisons. Though all industrialized societies started sending more people to prison and fewer to the gallows in the eighteenth century, it was in Enlightenment-inspired America that the taste for long-term, profoundly depersonalized punishment became most aggravated. The inhumanity of American prisons was as much a theme for Dickens, visiting America in 1842, as the cynicism of American lawyers. His shock when he saw the Eastern State Penitentiary, in Philadelphia—a “model” prison, at the time the most expensive public building ever constructed in the country, where every prisoner was kept in silent, separate confinement—still resonates:

I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers. . . . I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body: and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.

Not roused up to stay—that was the point. Once the procedure ends, the penalty begins, and, as long as the cruelty is routine, our civil responsibility toward the punished is over. We lock men up and forget about their existence. For Dickens, even the corrupt but communal debtors’ prisons of old London were better than this. “Don’t take it personally!”—that remains the slogan above the gate to the American prison Inferno. Nor is this merely a historian’s vision. Conrad Black, at the high end, has a scary and persuasive picture of how his counsel, the judge, and the prosecutors all merrily congratulated each other on their combined professional excellence just before sending him off to the hoosegow for several years. If a millionaire feels that way, imagine how the ordinary culprit must feel.

In place of abstraction, Stuntz argues for the saving grace of humane discretion. Basically, he thinks, we should go into court with an understanding of what a crime is and what justice is like, and then let common sense and compassion and specific circumstance take over. There’s a lovely scene in “The Castle,” the Australian movie about a family fighting eminent-domain eviction, where its hapless lawyer, asked in court to point to the specific part of the Australian constitution that the eviction violates, says desperately, “It’s . . . just the vibe of the thing.” For Stuntz, justice ought to be just the vibe of the thing—not one procedural error caught or one fact worked around. The criminal law should once again be more like the common law, with judges and juries not merely finding fact but making law on the basis of universal principles of fairness, circumstance, and seriousness, and crafting penalties to the exigencies of the crime.

The other argument—the Southern argument—is that this story puts too bright a face on the truth. The reality of American prisons, this argument runs, has nothing to do with the knots of procedural justice or the perversions of Enlightenment-era ideals. Prisons today operate less in the rehabilitative mode of the Northern reformers “than in a retributive mode that has long been practiced and promoted in the South,” Perkinson, an American-studies professor, writes. “American prisons trace their lineage not only back to Pennsylvania penitentiaries but to Texas slave plantations.” White supremacy is the real principle, this thesis holds, and racial domination the real end. In response to the apparent triumphs of the sixties, mass imprisonment became a way of reimposing Jim Crow. Blacks are now incarcerated seven times as often as whites. “The system of mass incarceration works to trap African Americans in a virtual (and literal) cage,” the legal scholar Michelle Alexander writes. Young black men pass quickly from a period of police harassment into a period of “formal control” (i.e., actual imprisonment) and then are doomed for life to a system of “invisible control.” Prevented from voting, legally discriminated against for the rest of their lives, most will cycle back through the prison system. The system, in this view, is not really broken; it is doing what it was designed to do. Alexander’s grim conclusion: “If mass incarceration is considered as a system of social control—specifically, racial control—then the system is a fantastic success.”

Northern impersonality and Southern revenge converge on a common American theme: a growing number of American prisons are now contracted out as for-profit businesses to for-profit companies. The companies are paid by the state, and their profit depends on spending as little as possible on the prisoners and the prisons. It’s hard to imagine any greater disconnect between public good and private profit: the interest of private prisons lies not in the obvious social good of having the minimum necessary number of inmates but in having as many as possible, housed as cheaply as possible. No more chilling document exists in recent American life than the 2005 annual report of the biggest of these firms, the Corrections Corporation of America. Here the company (which spends millions lobbying legislators) is obliged to caution its investors about the risk that somehow, somewhere, someone might turn off the spigot of convicted men:

Our growth is generally dependent upon our ability to obtain new contracts to develop and manage new correctional and detention facilities. . . . The demand for our facilities and services could be adversely affected by the relaxation of enforcement efforts, leniency in conviction and sentencing practices or through the decriminalization of certain activities that are currently proscribed by our criminal laws. For instance, any changes with respect to drugs and controlled substances or illegal immigration could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted, and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them.

Brecht could hardly have imagined such a document: a capitalist enterprise that feeds on the misery of man trying as hard as it can to be sure that nothing is done to decrease that misery.

Yet a spectre haunts all these accounts, North and South, whether process gone mad or penal colony writ large. It is that the epidemic of imprisonment seems to track the dramatic decline in crime over the same period. The more bad guys there are in prison, it appears, the less crime there has been in the streets. The real background to the prison boom, which shows up only sporadically in the prison literature, is the crime wave that preceded and overlapped it.

For those too young to recall the big-city crime wave of the sixties and seventies, it may seem like mere bogeyman history. For those whose entire childhood and adolescence were set against it, it is the crucial trauma in recent American life and explains much else that happened in the same period. It was the condition of the Upper West Side of Manhattan under liberal rule, far more than what had happened to Eastern Europe under socialism, that made neo-con polemics look persuasive. There really was, as Stuntz himself says, a liberal consensus on crime (“Wherever the line is between a merciful justice system and one that abandons all serious effort at crime control, the nation had crossed it”), and it really did have bad effects.

Yet if, in 1980, someone had predicted that by 2012 New York City would have a crime rate so low that violent crime would have largely disappeared as a subject of conversation, he would have seemed not so much hopeful as crazy. Thirty years ago, crime was supposed to be a permanent feature of the city, produced by an alienated underclass of super-predators; now it isn’t. Something good happened to change it, and you might have supposed that the change would be an opportunity for celebration and optimism. Instead, we mostly content ourselves with grudging and sardonic references to the silly side of gentrification, along with a few all-purpose explanations, like broken-window policing. This is a general human truth: things that work interest us less than things that don’t.

So what is the relation between mass incarceration and the decrease in crime? Certainly, in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, many experts became persuaded that there was no way to make bad people better; all you could do was warehouse them, for longer or shorter periods. The best research seemed to show, depressingly, that nothing works—that rehabilitation was a ruse. Then, in 1983, inmates at the maximum-security federal prison in Marion, Illinois, murdered two guards. Inmates had been (very occasionally) killing guards for a long time, but the timing of the murders, and the fact that they took place in a climate already prepared to believe that even ordinary humanity was wasted on the criminal classes, meant that the entire prison was put on permanent lockdown. A century and a half after absolute solitary first appeared in American prisons, it was reintroduced. Those terrible numbers began to grow.

And then, a decade later, crime started falling: across the country by a standard measure of about forty per cent; in New York City by as much as eighty per cent. By 2010, the crime rate in New York had seen its greatest decline since the Second World War; in 2002, there were fewer murders in Manhattan than there had been in any year since 1900. In social science, a cause sought is usually a muddle found; in life as we experience it, a crisis resolved is causality established. If a pill cures a headache, we do not ask too often if the headache might have gone away by itself.

All this ought to make the publication of Franklin E. Zimring’s new book, “The City That Became Safe,” a very big event. Zimring, a criminologist at Berkeley Law, has spent years crunching the numbers of what happened in New York in the context of what happened in the rest of America. One thing he teaches us is how little we know. The forty per cent drop across the continent—indeed, there was a decline throughout the Western world— took place for reasons that are as mysterious in suburban Ottawa as they are in the South Bronx. Zimring shows that the usual explanations—including demographic shifts—simply can’t account for what must be accounted for. This makes the international decline look slightly eerie: blackbirds drop from the sky, plagues slacken and end, and there seems no absolute reason that societies leap from one state to another over time. Trends and fashions and fads and pure contingencies happen in other parts of our social existence; it may be that there are fashions and cycles in criminal behavior, too, for reasons that are just as arbitrary.

But the additional forty per cent drop in crime that seems peculiar to New York finally succumbs to Zimring’s analysis. The change didn’t come from resolving the deep pathologies that the right fixated on—from jailing super predators, driving down the number of unwed mothers, altering welfare culture. Nor were there cures for the underlying causes pointed to by the left: injustice, discrimination, poverty. Nor were there any “Presto!” effects arising from secret patterns of increased abortions or the like. The city didn’t get much richer; it didn’t get much poorer. There was no significant change in the ethnic makeup or the average wealth or educational levels of New Yorkers as violent crime more or less vanished. “Broken windows” or “turnstile jumping” policing, that is, cracking down on small visible offenses in order to create an atmosphere that refused to license crime, seems to have had a negligible effect; there was, Zimring writes, a great difference between the slogans and the substance of the time. (Arrests for “visible” nonviolent crime—e.g., street prostitution and public gambling—mostly went downthrough the period.)

Instead, small acts of social engineering, designed simply to stop crimes from happening, helped stop crime. In the nineties, the N.Y.P.D. began to control crime not by fighting minor crimes in safe places but by putting lots of cops in places where lots of crimes happened—“hot-spot policing.” The cops also began an aggressive, controversial program of “stop and frisk”—“designed to catch the sharks, not the dolphins,” as Jack Maple, one of its originators, described it—that involved what’s called pejoratively “profiling.” This was not so much racial, since in any given neighborhood all the suspects were likely to be of the same race or color, as social, involving the thousand small clues that policemen recognized already. Minority communities, Zimring emphasizes, paid a disproportionate price in kids stopped and frisked, and detained, but they also earned a disproportionate gain in crime reduced. “The poor pay more and get more” is Zimring’s way of putting it. He believes that a “light” program of stop-and-frisk could be less alienating and just as effective, and that by bringing down urban crime stop-and-frisk had the net effect of greatly reducing the number of poor minority kids in prison for long stretches.

Zimring insists, plausibly, that he is offering a radical and optimistic rewriting of theories of what crime is and where criminals are, not least because it disconnects crime and minorities. “In 1961, twenty six percent of New York City’s population was minority African American or Hispanic. Now, half of New York’s population is—and what that does in an enormously hopeful way is to destroy the rude assumptions of supply side criminology,” he says. By “supply side criminology,” he means the conservative theory of crime that claimed that social circumstances produced a certain net amount of crime waiting to be expressed; if you stopped it here, it broke out there. The only way to stop crime was to lock up all the potential criminals. In truth, criminal activity seems like most other human choices—a question of contingent occasions and opportunity. Crime is not the consequence of a set number of criminals; criminals are the consequence of a set number of opportunities to commit crimes. Close down the open drug market in Washington Square, and it does not automatically migrate to Tompkins Square Park. It just stops, or the dealers go indoors, where dealing goes on but violent crime does not.

And, in a virtuous cycle, the decreased prevalence of crime fuels a decrease in the prevalence of crime. When your friends are no longer doing street robberies, you’re less likely to do them. Zimring said, in a recent interview, “Remember, nobody ever made a living mugging. There’s no minimum wage in violent crime.” In a sense, he argues, it’s recreational, part of a life style: “Crime is a routine behavior; it’s a thing people do when they get used to doing it.” And therein lies its essential fragility. Crime ends as a result of “cyclical forces operating on situational and contingent things rather than from finding deeply motivated essential linkages.” Conservatives don’t like this view because it shows that being tough doesn’t help; liberals don’t like it because apparently being nice doesn’t help, either. Curbing crime does not depend on reversing social pathologies or alleviating social grievances; it depends on erecting small, annoying barriers to entry.

One fact stands out. While the rest of the country, over the same twenty-year period, saw the growth in incarceration that led to our current astonishing numbers, New York, despite the Rockefeller drug laws, saw a marked decrease in its number of inmates. “New York City, in the midst of a dramatic reduction in crime, is locking up a much smaller number of people, and particularly of young people, than it was at the height of the crime wave,” Zimring observes. Whatever happened to make street crime fall, it had nothing to do with putting more men in prison. The logic is self-evident if we just transfer it to the realm of white-collar crime: we easily accept that there is no net sum of white-collar crime waiting to happen, no inscrutable generation of super-predators produced by Dewar’s-guzzling dads and scaly M.B.A. profs; if you stop an embezzlement scheme here on Third Avenue, another doesn’t naturally start in the next office building. White-collar crime happens through an intersection of pathology and opportunity; getting the S.E.C. busy ending the opportunity is a good way to limit the range of the pathology.

Social trends deeper and less visible to us may appear as future historians analyze what went on. Something other than policing may explain things—just as the coming of cheap credit cards and state lotteries probably did as much to weaken the Mafia’s Five Families in New York, who had depended on loan sharking and numbers running, as the F.B.I. could. It is at least possible, for instance, that the coming of the mobile phone helped drive drug dealing indoors, in ways that helped drive down crime. It may be that the real value of hot spot and stop-and-frisk was that it provided a single game plan that the police believed in; as military history reveals, a bad plan is often better than no plan, especially if the people on the other side think it’s a good plan. But one thing is sure: social epidemics, of crime or of punishment, can be cured more quickly than we might hope with simpler and more superficial mechanisms than we imagine. Throwing a Band-Aid over a bad wound is actually a decent strategy, if the Band-Aid helps the wound to heal itself.

Which leads, further, to one piece of radical common sense: since prison plays at best a small role in stopping even violent crime, very few people, rich or poor, should be in prison for a nonviolent crime. Neither the streets nor the society is made safer by having marijuana users or peddlers locked up, let alone with the horrific sentences now dispensed so easily. For that matter, no social good is served by having the embezzler or the Ponzi schemer locked in a cage for the rest of his life, rather than having him bankrupt and doing community service in the South Bronx for the next decade or two. Would we actually have more fraud and looting of shareholder value if the perpetrators knew that they would lose their bank accounts and their reputation, and have to do community service seven days a week for five years? It seems likely that anyone for whom those sanctions aren’t sufficient is someone for whom no sanctions are ever going to be sufficient. Zimring’s research shows clearly that, if crime drops on the street, criminals coming out of prison stop committing crimes. What matters is the incidence of crime in the world, and the continuity of a culture of crime, not some “lesson learned” in prison.

At the same time, the ugly side of stop-and-frisk can be alleviated. To catch sharks and not dolphins, Zimring’s work suggests, we need to adjust the size of the holes in the nets—to make crimes that are the occasion for stop-and-frisks real crimes, not crimes like marijuana possession. When the New York City police stopped and frisked kids, the main goal was not to jail them for having pot but to get their fingerprints, so that they could be identified if they committed a more serious crime. But all over America the opposite happens: marijuana possession becomes the serious crime. The cost is so enormous, though, in lives ruined and money spent, that the obvious thing to do is not to enforce the law less but to change it now. Dr. Johnson said once that manners make law, and that when manners alter, the law must, too. It’s obvious that marijuana is now an almost universally accepted drug in America: it is not only used casually (which has been true for decades) but also talked about casually on television and in the movies (which has not). One need only watch any stoner movie to see that the perceived risks of smoking dope are not that you’ll get arrested but that you’ll get in trouble with a rival frat or look like an idiot to women. The decriminalization of marijuana would help end the epidemic of imprisonment.

The rate of incarceration in most other rich, free countries, whatever the differences in their histories, is remarkably steady. In countries with Napoleonic justice or common law or some mixture of the two, in countries with adversarial systems and in those with magisterial ones, whether the country once had brutal plantation-style penal colonies, as France did, or was once itself a brutal plantation-style penal colony, like Australia, the natural rate of incarceration seems to hover right around a hundred men per hundred thousand people. (That doesn’t mean it doesn’t get lower in rich, homogeneous countries—just that it never gets much higher in countries otherwise like our own.) It seems that one man in every thousand once in a while does a truly bad thing. All other things being equal, the point of a justice system should be to identify that thousandth guy, find a way to keep him from harming other people, and give everyone else a break.

Epidemics seldom end with miracle cures. Most of the time in the history of medicine, the best way to end disease was to build a better sewer and get people to wash their hands. “Merely chipping away at the problem around the edges” is usually the very best thing to do with a problem; keep chipping away patiently and, eventually, you get to its heart. To read the literature on crime before it dropped is to see the same kind of dystopian despair we find in the new literature of punishment: we’d have to end poverty, or eradicate the ghettos, or declare war on the broken family, or the like, in order to end the crime wave. The truth is, a series of small actions and events ended up eliminating a problem that seemed to hang over everything. There was no miracle cure, just the intercession of a thousand smaller sanities. Ending sentencing for drug misdemeanors, decriminalizing marijuana, leaving judges free to use common sense (and, where possible, getting judges who are judges rather than politicians)—many small acts are possible that will help end the epidemic of imprisonment as they helped end the plague of crime.

“Oh, I have taken too little care of this!” King Lear cries out on the heath in his moment of vision. “Take physic, pomp; expose thyself to feel what wretches feel.” “This” changes; in Shakespeare’s time, it was flat-out peasant poverty that starved some and drove others as mad as poor Tom. In Dickens’s and Hugo’s time, it was the industrial revolution that drove kids to mines. But every society has a poor storm that wretches suffer in, and the attitude is always the same: either that the wretches, already dehumanized by their suffering, deserve no pity or that the oppressed, overwhelmed by injustice, will have to wait for a better world. At every moment, the injustice seems inseparable from the community’s life, and in every case the arguments for keeping the system in place were that you would have to revolutionize the entire social order to change it—which then became the argument for revolutionizing the entire social order. In every case, humanity and common sense made the insoluble problem just get up and go away. Prisons are our this. We need take more care. ♦

Read more http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2012/01/30/120130crat_atlarge_gopnik#ixzz1sDutH2NI

***

Liberal Academic, Tea Party Leader Rethinking Crime Policy

The odd alliance changing the way we think about crime.

by Andrew Romano |

Tea party leaders tend not to break bread with black liberals, media centrists, and conservative plutocrats for a reason: they rarely agree on much. But by the time Mark Meckler arrived in Austin, Texas, on Feb. 9, he was fed up with being a Tea Party bigwig. He was ready for something different.

Like a dinner at Vespaio Ristorante with civil-rights activist Benjamin Chavis, MSNBC host Dylan Ratigan, and Texas oilman Tim Dunn.

The topic of conversation wasn’t Obamacare or the national debt or any of the other things that Meckler—who was about to quit the Tea Party Patriots, a group he’d cofounded in 2009—had already spent plenty of time obsessing over. Instead, it was a subject that Tea Partiers usually ignore: criminal-justice reform.

Of all the problems in America today, none is both as obvious and as overlooked as the colossal human catastrophe that is our criminal-justice system. Prisons are overflowing. The government is broke. Communities are being destroyed. And yet the country’s cowed, uncreative politicians are still stuck in lock-’em-up mode: a stale ideology that demands stricter drug laws, tougher policing, and more incarceration, then tars every dissenter as “soft on crime.” As a result, the U.S. is now paying $200 billion a year, according to the late Harvard criminal-justice scholar William Stuntz, to arrest, try, and incarcerate nearly 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, even though it’s home to only 5 percent of the world’s inhabitants. Crack use may have subsided, violent crime may have plummeted, and so-called superpredators may have gone the way of Bigfoot. But that hasn’t stopped us from separating millions of disproportionately poor, disproportionately black men from their families and communities and consigning them to a vicious cycle of stigmatization and recidivism instead.

Meckler, Chavis, Ratigan, and Dunn had come to Austin in search of a better way. Their guide was David Kennedy, a criminologist at John Jay College in New York. Over margherita pies, Kennedy began to tell the group about his innovative Ceasefire approach to crime control: a cheaper, more stripped-down, post-War-on-Drugs policing methodology that has dramatically lowered the homicide rate in some of America’s most dangerous cities.

Meckler was energized. This was exactly the sort of second act he had in mind—a proven, nonideological way to remove “the heavy hand of the state,” he tells Newsweek, “and give these communities the freedom to govern themselves.”

And so after four hours at Vespaio, Meckler and the others had agreed to form a new alliance. Their goal: to take Kennedy’s methods national. “It was a meeting of the minds, and of what are usually opposing cultures, that really represents the larger evolution going on right now,” Kennedy says. “I was truly amazed.”

By finding common ground on the unlikeliest of issues, could a Tea Party leader and a liberal academic actually help us overcome our criminal-justice impasse? One rustic Italian dinner does not, of course, a revolution make. But Kennedy is right: there is a “larger evolution going on right now.” It’s a transformation that is being fueled in part by penny-pinching, small-government conservatives like Meckler—conservatives who are realizing that it’s far too invasive, expensive, and destructive to continue incarcerating every wrongdoer for every infraction. And because conservative activists don’t have to tiptoe through the toxic crime debate like their office-seeking counterparts—who increasingly take their cues from the grassroots anyway—Kennedy & Co. are starting to believe that a groundswell among Meckler types could be the thing that finally gets criminal-justice reform off the ground.

As the son of an LAPD reserve policewoman turned Nevada County, Calif., corrections officer, Meckler was always primed to be skeptical of the GOP’s tough-on-crime talking points. “Having grown up around law-enforcement folks, I know a large number who are very conservative and still think the war on drugs has been an immense failure,” he says. “That’s not a new position they’ve come to. I’ve been hearing this literally my whole life.”

But it wasn’t until he’d spent some time in the Tea Party, with its obsessive focus on balanced budgets and smaller government, that Meckler realized how well his conservative principles jibed with criminal-justice reform. It was all there, he says: a ballooning tab that was “busting state budgets”; a top-down, one-size-fits-all style of policing and imprisonment that was “making it hard for [former criminals] to become productive members of society”; and communities that had “lost the ability to take care of themselves” because they were “occupied” by agents of the state. “On the right, we always talk about self-governance,” Meckler explains. “So I thought, why haven’t we been applying those ideas to the criminal-justice system?”

He isn’t the only conservative to come to that conclusion. Inspired by the Tea Party ethos, heavyweight GOP governors such as Bobby Jindaland Mitch Danielsare now working to soften sentences, reduce recidivism, and cut costs in their home states. Meanwhile, Right on Crime, a Texas-based conservative group backed by Newt Gingrich, Jeb Bush, and Grover Norquist, is championing reform on the national stage. As the outfit’s mission statement puts it, there’s nothing “conservative” about “spend[ing] vast amounts of taxpayer money on a strategy without asking whether it is providing taxpayers with the best public-safety return on their investment.” Right on Crime points to the Lone Star State—which recently reduced its incarceration rate by 8 percent, cut crime by 6 percent, and saved $2 billion on prison construction by rerouting inmates to drug courts and treatment facilities—as an example of where that mindset can lead.

Earlier this year Meckler read Kennedy’s 2011 memoir, Don’t Shoot: One Man, a Street Fellowship, and the End of Violence in Inner-City America. He felt an immediate kinship. After two decades of working with inner-city cops to curb violent crime, Kennedy seemed to have cracked some kind of secret code. In the book (and later, at dinner) he explained what he’d learned. That no one in these communities really likes shootings, gang members included. That the number of gang members personally involved in such incidents is minuscule. That when the cops suddenly crack down on a few of these violent offenders and then invite the others to talk, the others do, in fact, show up (and listen).

That whenever the cops give these gangsters a choice between (a) shooting people and going to prison or (b) not shooting people and going on with their lives, they almost always choose the latter. And that, as a result, murder rates tend to drop by staggering margins wherever these methods are applied. Kennedy’s program didn’t hew to liberal orthodoxy, placing the blame on society rather than the criminals themselves. Nor did it reflect conservative dogma. It just worked. “It was almost as if David had been reading what we’d been saying and was trying to speak our language,” Meckler says. “But he wasn’t. It was entirely organic.”

That whenever the cops give these gangsters a choice between (a) shooting people and going to prison or (b) not shooting people and going on with their lives, they almost always choose the latter. And that, as a result, murder rates tend to drop by staggering margins wherever these methods are applied. Kennedy’s program didn’t hew to liberal orthodoxy, placing the blame on society rather than the criminals themselves. Nor did it reflect conservative dogma. It just worked. “It was almost as if David had been reading what we’d been saying and was trying to speak our language,” Meckler says. “But he wasn’t. It was entirely organic.”

Hence the summit in Austin and the new alliance. Later this month Meckler will launch his post–Tea Party Patriots initiative: a group called Citizens for Self Governance that will seek to “address any issue of self-governance that crosses party lines.” Criminal-justice reform will top the list. While the Vespaio team has “not yet formalized anything,” says Meckler (“we are having continuing discussions about that”), he believes that he’ll soon be working alongside Chavis, Dunn, and Ratigan to help Kennedy’s ready-to-go strategies become the national template for violent-crime control. Kennedy, for his part, is excited to have Meckler on board. “The right is really good at organizing, fundraising, and playing the long game,” he says. “If that kind of energy is applied to criminal-justice reform, then it could really make a difference.”

***

New York Times

***

New York Times

U.S. prison population dwarfs that of other nations

By Adam Liptak

Published: Wednesday, April 23, 2008

The United States has less than 5 percent of the world's population. But it has almost a quarter of the world's prisoners.

Indeed, the United States leads the world in producing prisoners, a reflection of a relatively recent and now entirely distinctive American approach to crime and punishment. Americans are locked up for crimes — from writing bad checks to using drugs — that would rarely produce prison sentences in other countries. And in particular they are kept incarcerated far longer than prisoners in other nations.

Criminologists and legal scholars in other industrialized nations say they are mystified and appalled by the number and length of American prison sentences.

The United States has, for instance, 2.3 million criminals behind bars, more than any other nation, according to data maintained by the International Center for Prison Studies at King's College London.

China, which is four times more populous than the United States, is a distant second, with 1.6 million people in prison. (That number excludes hundreds of thousands of people held in administrative detention, most of them in China's extrajudicial system of re-education through labor, which often singles out political activists who have not committed crimes.)

San Marino, with a population of about 30,000, is at the end of the long list of 218 countries compiled by the center. It has a single prisoner.

The United States comes in first, too, on a more meaningful list from the prison studies center, the one ranked in order of the incarceration rates. It has 751 people in prison or jail for every 100,000 in population. (If you count only adults, one in 100 Americans is locked up.)

The only other major industrialized nation that even comes close is Russia, with 627 prisoners for every 100,000 people. The others have much lower rates. England's rate is 151; Germany's is 88; and Japan's is 63.

The median among all nations is about 125, roughly a sixth of the American rate.

There is little question that the high incarceration rate here has helped drive down crime, though there is debate about how much.

Criminologists and legal experts here and abroad point to a tangle of factors to explain America's extraordinary incarceration rate: higher levels of violent crime, harsher sentencing laws, a legacy of racial turmoil, a special fervor in combating illegal drugs, the American temperament, and the lack of a social safety net. Even democracy plays a role, as judges — many of whom are elected, another American anomaly — yield to populist demands for tough justice.

Whatever the reason, the gap between American justice and that of the rest of the world is enormous and growing.

It used to be that Europeans came to the United States to study its prison systems. They came away impressed.

"In no country is criminal justice administered with more mildness than in the United States," Alexis de Tocqueville, who toured American penitentiaries in 1831, wrote in "Democracy in America."

No more.

"Far from serving as a model for the world, contemporary America is viewed with horror," James Whitman, a specialist in comparative law at Yale, wrote last year in Social Research. "Certainly there are no European governments sending delegations to learn from us about how to manage prisons."

Prison sentences here have become "vastly harsher than in any other country to which the United States would ordinarily be compared," Michael Tonry, a leading authority on crime policy, wrote in "The Handbook of Crime and Punishment."

Indeed, said Vivien Stern, a research fellow at the prison studies center in London, the American incarceration rate has made the United States "a rogue state, a country that has made a decision not to follow what is a normal Western approach."

The spike in American incarceration rates is quite recent. From 1925 to 1975, the rate remained stable, around 110 people in prison per 100,000 people. It shot up with the movement to get tough on crime in the late 1970s. (These numbers exclude people held in jails, as comprehensive information on prisoners held in state and local jails was not collected until relatively recently.)

The nation's relatively high violent crime rate, partly driven by the much easier availability of guns here, helps explain the number of people in American prisons.

"The assault rate in New York and London is not that much different," said Marc Mauer, the executive director of the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy group. "But if you look at the murder rate, particularly with firearms, it's much higher."

Despite the recent decline in the murder rate in the United States, it is still about four times that of many nations in Western Europe.

But that is only a partial explanation. The United States, in fact, has relatively low rates of nonviolent crime. It has lower burglary and robbery rates than Australia, Canada and England.

People who commit nonviolent crimes in the rest of the world are less likely to receive prison time and certainly less likely to receive long sentences. The United States is, for instance, the only advanced country that incarcerates people for minor property crimes like passing bad checks, Whitman wrote.

Efforts to combat illegal drugs play a major role in explaining long prison sentences in the United States as well. In 1980, there were about 40,000 people in American jails and prisons for drug crimes. These days, there are almost 500,000.

Those figures have drawn contempt from European critics. "The U.S. pursues the war on drugs with an ignorant fanaticism," said Stern of King's College.

Many American prosecutors, on the other hand, say that locking up people involved in the drug trade is imperative, as it helps thwart demand for illegal drugs and drives down other kinds of crime. Attorney General Michael Mukasey, for instance, has fought hard to prevent the early release of people in federal prison on crack cocaine offenses, saying that many of them "are among the most serious and violent offenders."

Still, it is the length of sentences that truly distinguishes American prison policy. Indeed, the mere number of sentences imposed here would not place the United States at the top of the incarceration lists. If lists were compiled based on annual admissions to prison per capita, several European countries would outpace the United States. But American prison stays are much longer, so the total incarceration rate is higher.

Burglars in the United States serve an average of 16 months in prison, according to Mauer, compared with 5 months in Canada and 7 months in England.

Many specialists dismissed race as an important distinguishing factor in the American prison rate. It is true that blacks are much more likely to be imprisoned than other groups in the United States, but that is not a particularly distinctive phenomenon. Minorities in Canada, Britain and Australia are also disproportionately represented in those nation's prisons, and the ratios are similar to or larger than those in the United States.

Some scholars have found that English-speaking nations have higher prison rates.

"Although it is not at all clear what it is about Anglo-Saxon culture that makes predominantly English-speaking countries especially punitive, they are," Tonry wrote last year in "Crime, Punishment and Politics in Comparative Perspective."

"It could be related to economies that are more capitalistic and political cultures that are less social democratic than those of most European countries," Tonry wrote. "Or it could have something to do with the Protestant religions with strong Calvinist overtones that were long influential."

The American character — self-reliant, independent, judgmental — also plays a role.

"America is a comparatively tough place, which puts a strong emphasis on individual responsibility," Whitman of Yale wrote. "That attitude has shown up in the American criminal justice of the last 30 years."

French-speaking countries, by contrast, have "comparatively mild penal policies," Tonry wrote.

Of course, sentencing policies within the United States are not monolithic, and national comparisons can be misleading.

"Minnesota looks more like Sweden than like Texas," said Mauer of the Sentencing Project. (Sweden imprisons about 80 people per 100,000 of population; Minnesota, about 300; and Texas, almost 1,000. Maine has the lowest incarceration rate in the United States, at 273; and Louisiana the highest, at 1,138.)

Whatever the reasons, there is little dispute that America's exceptional incarceration rate has had an impact on crime.

"As one might expect, a good case can be made that fewer Americans are now being victimized" thanks to the tougher crime policies, Paul Cassell, an authority on sentencing and a former federal judge, wrote in The Stanford Law Review.

From 1981 to 1996, according to Justice Department statistics, the risk of punishment rose in the United States and fell in England. The crime rates predictably moved in the opposite directions, falling in the United States and rising in England.

"These figures," Cassell wrote, "should give one pause before too quickly concluding that European sentences are appropriate."

Other commentators were more definitive. "The simple truth is that imprisonment works," wrote Kent Scheidegger and Michael Rushford of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in The Stanford Law and Policy Review. "Locking up criminals for longer periods reduces the level of crime. The benefits of doing so far offset the costs."

There is a counterexample, however, to the north. "Rises and falls in Canada's crime rate have closely paralleled America's for 40 years," Tonry wrote last year. "But its imprisonment rate has remained stable."

Several specialists here and abroad pointed to a surprising explanation for the high incarceration rate in the United States: democracy.

Most state court judges and prosecutors in the United States are elected and are therefore sensitive to a public that is, according to opinion polls, generally in favor of tough crime policies. In the rest of the world, criminal justice professionals tend to be civil servants who are insulated from popular demands for tough sentencing.

Whitman, who has studied Tocqueville's work on American penitentiaries, was asked what accounted for America's booming prison population.

"Unfortunately, a lot of the answer is democracy — just what Tocqueville was talking about," he said. "We have a highly politicized criminal justice system."

*

One in 31 U.S. Adults are Behind Bars, on Parole or Probation

Contact: Jessica Riordan, 215.575.4886 and Andrew McDonald, 202.552.2178

Washington, DC - 03/02/2009 - Explosive growth in the number of people on probation or parole has propelled the population of the American corrections system to more than 7.3 million, or 1 in every 31 U.S. adults, according to a report released today by the Pew Center on the States. The vast majority of these offenders live in the community, yet new data in the report finds that nearly 90 percent of state corrections dollars are spent on prisons. One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections examines the scale and cost of prison, jail, probation and parole in each of the 50 states, and provides a blueprint for states to cut both crime and spending by reallocating prison expenses to fund stronger supervision of the large number of offenders in the community.

"Most states are facing serious budget deficits,"said Susan Urahn, managing director of The Pew Center on the States. "Every single one of them should be making smart investments in community corrections that will help them cut costs and improve outcomes."

In the past two decades, state general fund spending on corrections increased by more than 300 percent, outpacing other essential government services from education, to transportation and public assistance. Only Medicaid spending has grown faster. Today, corrections imposes a national taxpayer burden of $68 billion a year. Despite this increased spending, recidivism rates have remained largely unchanged.

Research shows that strong community supervision programs for lower-risk, non-violent offenders not only cost significantly less than incarceration but, when appropriately resourced and managed, can cut recidivism by as much as 30 percent. Diverting these offenders to community supervision programs also frees up prison beds needed to house violent offenders, and can offer budget makers additional resources for other pressing public priorities.

One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections provides a detailed look at who is in the corrections system and which states have the highest populations of offenders behind bars and in the community. Key findings include:

"Most states are facing serious budget deficits,"said Susan Urahn, managing director of The Pew Center on the States. "Every single one of them should be making smart investments in community corrections that will help them cut costs and improve outcomes."

In the past two decades, state general fund spending on corrections increased by more than 300 percent, outpacing other essential government services from education, to transportation and public assistance. Only Medicaid spending has grown faster. Today, corrections imposes a national taxpayer burden of $68 billion a year. Despite this increased spending, recidivism rates have remained largely unchanged.

Research shows that strong community supervision programs for lower-risk, non-violent offenders not only cost significantly less than incarceration but, when appropriately resourced and managed, can cut recidivism by as much as 30 percent. Diverting these offenders to community supervision programs also frees up prison beds needed to house violent offenders, and can offer budget makers additional resources for other pressing public priorities.

One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections provides a detailed look at who is in the corrections system and which states have the highest populations of offenders behind bars and in the community. Key findings include:

- One in 31 adults in America is in prison or jail, or on probation or parole. Twenty-five years ago, the rate was 1 in 77.

- Overall, two-thirds of offenders are in the community, not behind bars. 1 in 45 adults is on probation or parole and 1 in 100 is in prison or jail. The proportion of offenders behind bars versus in the community has changed very little over the past 25 years, despite the addition of 1.1 million prison beds.

- Correctional control rates are highly concentrated by race and geography: 1 in 11 black adults (9.2 percent) versus 1 in 27 Hispanic adults (3.7 percent) and 1 in 45 white adults (2.2 percent); 1 in 18 men (5.5 percent) versus 1 in 89 women (1.1 percent). The rates can be extremely high in certain neighborhoods. In one block-group of Detroit’s East Side, for example, 1 in 7 adult men (14.3 percent) is under correctional control.

- Georgia, where 1 in 13 adults is behind bars or under community supervision, leads the top five states that also include Idaho, Texas, Massachusetts, Ohio and the District of Columbia.

While total correctional spending figures have been available before, new data collected by the Pew Center on the States for the report provides the first breakdown of correctional spending by prisons, probation and parole in the past seven years:

- In FY 2008, the 34 states for which data are available spent $18.65 billion on prisons (88 percent of corrections spending), but only $2.52 billion on probation and parole (12 percent).

- For eight states where 25 years of data were available, spending on prisons grew by $4.74 billion from FY 1983 to FY 2008, while probation and parole spending increased by only $652 million. This means that while prisons accounted for one-third of the population growth, they consumed 88 percent of the new corrections expenditures.

- The 33 states that were able to provide data reported spending as much as 22 times more per day to manage prison inmates than to supervise offenders in the community. The reported average inmate cost was $79 per day, or nearly $29,000 per year. The average cost of managing an offender in the community ranged from $3.42 per day for probationers to $7.47 per day for parolees, or about $1,250 to $2,750 a year.

One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections provides states with a blueprint and specific case studies for strengthening their community corrections systems, saving money and reducing crime. Research-based recommendations include:

- Sort offenders by risk to public safety to determine appropriate levels of supervision;

- Base intervention programs on sound research about what works to reduce recidivism;

- Harness advances in supervision technology such as electronic monitoring and rapid-result alcohol and drug tests;

- Impose swift and certain sanctions for offenders who break the rules of their release but who do not commit new crimes; and

- Create incentives for offenders and supervision agencies to succeed, and monitor their performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment